I. INTRODUCTION

The year 1819 was a turing point for the revolutionary forces in the northern half of Spanish South America. For the first time, Bolivar's men were able to liberate large areas permanently and they then drove the Spaniards from the continent with a string of victories --Boyaca (1819), Carabobo (1821), Pichincha (1822), and Ayacucho (1824).

From the miniatures standpoint this is also the best period to ex-amine for in the wake of victory came the first real uniformity in organization and clothing. However, studies of Bolivar's army even in this period are still complicated by (1) the patriot mania for reorganization, (2) the continuing (though understandable) defic-iences of the patriot supply service, and (3) what one Venezuelan author has called, "the problems of our painters, who, lacking precise data, had to resort to their imaginations."

Also, this article concentrates on Bolivar's regulars. The militia were generally useless, but varying numbers of guerillas often played an important part. These irregulars in civilian dress were more loyal to specific chiefs than abstract principles, aria fought a savage war with pistol, lance, bow, machete, or whatever else was at hand.

In painting a south American army, it should be remembered that many patriot soldiers were blacks, Indians, or mixtures of the various races. Even the Caucasian creoles often had a darker complexion than the flesh color manufacturers normally put out. Sometimes, carrying on the tradition of the old Spanish colonial militia, the patriots would form an entire unit from one race. A prime example was the black Bn. Santander. However, in other cases the pressing need for men created considerable mixing.

II. INFANTRY

Organization.

The patriot goal was an 800-man battalion/regimentcontaining 1 grenadier, 1 light, and 6 line companies. However, there were always attrition problems, and often two or three companies would be removed to form the nucleus of a new regiment. As a result, even in 1822 the army showed rosters of 200-500 effectives per battalion, with the average around 400.

Several regiments were designated light infantry but the line carried muskets by 1823. Units were generally named after either a person -- Bn. Santander, Girardot -- or a place -- Bn. Orinoco, Magdalena, Cartagena, Cauca.

Uniforms

Uniforms

Knotel gives the standard dress as blue jacket, long trousers, and cuffs; red collar, epaulettes, trousers stripe, and piping on cuffs and jacket edge; white turnbacks, crossbelts, and stockings; black shoes; silver buttons; and black. shako with silver plate and red pompom.

Left ot right: Line infantry or artillery (well supplied), Line infantry or artillery (poorly supplied), Grenadier Peruvian Legion, and Regt de Honor de Paez

A Venezuelan historian re-creates the Bn. Bravos de Apure in much the same way except for (1) red cuffs and turnbacks, (Z) no trousers stripe, and (3) instead of a shako plate the patriot cockade -- yellow outside, blue, and red.

However, visitors found a much greater variety of uniforms. Colonel Duane claimed to have seer. (1) blue, red, and yellow jackets, (2) blue red, and yellow facings, (3) white, red, and yellow waistcoats, and (4) white, red, blue, and yellow trousers. One specific combination for an unnamed battalion was blue -jacket., red waistcoat, and yellow trousers. Leather shakes with the patriot cockade were common, but Duane also reported bicorns, straw hats, and Italian caps.

From the information of other observers it appears that many of the wilder combinations were worn by officers while the men stuck to blue coasts and trousers. Bolivar did complain of the officers' practice of wearing nonregulation uniforms and festooning themselves with plumes, gold frogging, and other extra ornaments.

The observers also noted a general lack of shoes or boots, so that many men went barefoot.

Two other regiments for which details are known are the Bn. Bogota --green facings and epaulettes--and the Bn. Istmo (Isthmian, i.e. Panamanian)--one pair of white and one pair of green trousers. Finally, tic veterans of various victories were sometimes awarded a small shield : to be worn sleeve. These shields were gen-erally yellow with the name of the battle inscribed, an', surrounded by a laurel wreath.

Standards

Most of the -standards were apparently based on the patriot tricolor, horizontal stripes of yellow, blue, and with the yellow top stripe as wide as the other two put together .

Some regiments, like the Bn. Istmo, left this plain. Others put . their names on the center blue stripe, and added honors.

III. CAVALRY

Organization

Organization

Several competing models were in vogue.Squadrons tried to have either t companies of 80 men apiece. or 3 of 50. A regiment might contain either one or two squadrons, and there were the usual problems with recruitment- and effective strength.

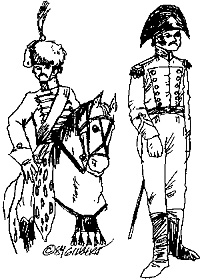

Guardia de Honor Cav. Regt trooper and a General

The cavalry went in for flamboyant names: the Regiment of Venqeance, the Regiment of Death, the Superb Dragoons, the Valiant Chasseurs. But whatever the title, there were only two types, light and line, and even these were not always easy to tell apart. Line cavalry carried sometimes pistols and swords and always the lance: "the anchor of the Republic and the divine instrument of its salvation", as Bolivar's Secretary of War once called it. The light horse had sabres, carbines, and occationally lances. "Dragoons" were not used as mounted infantry. In fact, few of the horsemen seem to have trusted their firearms. At the mass cavalry engagement of Junin (1824), not a shot was fired by

Uniforms

Same remarks as for infantry in the same uniform as the patriot foot and a blue shabraque edged yellow and then red. However, Duane aqain recorded a variety of uniforms.

Some details are known about two of the more elite regiments. The Sacred Squadron (Escuadron Sagrado) seems to have been composed entirely of officers for whom commands were temporarily lacking. The unit had red shakos, jackets, trousers, and shabragues, s, apparently with gold chest froqging and other trim.

The Regimiento de Honor de Paez was a crack lancer regiment formed out of the best men in his command by Jose Antonio Paez, noted cavalry general and later President of Venezuela. the two 150-man quadrons apparently wore the uniform of Britain's 1st Royal Draqoons -- helmet, red coat with blue facings an,:` yellow trim, and and blue trousers with yellow stripes -- plus a cape.

Observers found the lances of Bolicar's army to be longer, thinner and more flexible than those in Europe. There seem to have been three main styles of pennon: (1) none, (2) a red swallowtail, and (3) a yellow-blue-red tripletail. Carbines were mostly sawed-off muskets. For standards, see under part II, INFANTRY.

IV. ARTILLERY, ENGINEERS, GENERALS

From 1814 until 1822 the patriot field artillery was most. noticeable by its absence. After that date a small number of 100-man companies were armed wit' pieces captured, bought, or dragged out of coastal fortresses.

Knotel depicts a gunner in blue jacket, trousers, collar, and red epaulettes, trousers stripe, and piping on collar, cuffs, and jacket edge, white stockings; black shoes and tons; and black shako with red pompom and gold plate.

The only engineer type seem to have been a few staff officers. A single 90-man company of guardsappers (zapadores) was formed in 1815 with black shakos, red jackets, green collars and cuffs with gold trim, and white trousers. This was probably the same company that was reported .t Boyaca and Carabobo.

Although generals often wore what they pleased, one formal model crops up in many portraits. This consists of blue long coat with red collar, cuffs, lapels, and turnbacks. Ornate gold trim and piping -- a notable form of which is gold-palm leaf designs on collar, cuffs, and lapels. Since the pictures are portraits more detail is generally lacking. However, other information suggests black boots; black bicorn with patriot cockade and possibly gold tape edging; and trousers either white or dark blue with a red stripe. Gold epaulettes.

A variation on the above has no lapels, leaving a plain blue jacket front except for a gold line of piping.

V. GUARDIA DE HONOR

Originally created as a tight little organization, the Guard soon grew as one regiment after another was added, usually to reward its valor in some battle. At its height the Guard contained 10 infantry battalions and 6 cavalry squadrons. Most of the regiments disappeared around 1830 when Grand Colombia broke up into Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador.

The Bn. Rifles (1st Venezuelan Rifle Regt.) and Bn. Carabobo (British Legion) were originally foreign units which have been described elsewhere (in a past issue of the Courier). Among the other regiments: Bn. Granaderos (Grenadiers): One of the oldest formations. Founded as a single 80-man company in 1815, the unit later grew into 4 companies and 500 men, apparently went through a period as the "Bn. Barcelona", then returned to its old name with 6 companies (1 light) and 800 effectives, and still later added two more companies.

The Granaderos had by 1822 adopted a dress uniform virtually duplicating Napoleon's Old Guard qrenadier -- blue coat, bearskin, etc.

Bn. Anzoategui (named after a patriot leader): Recruited from the eastern Venezuelan coast, the unit won the sobriquet "Valeroso" for its storming of Puerto Cabello in 1823. During its career, Anzoategui was organized into 1 grenadier, 1 light, and 5 (later 6) line com-panies, fluctuating from 400 to 700 Men.

The battalion wore a short coat of "Turkish blue" officially indigo, or deep gray blue, but depicted or supposed as medium blue, red collar cuffs, turnbacks, and poping. Black shakos.

Bn. Vencedor en Boyaca (Victorious at Boyaca) : A decisive charge in that battle renamed the old Bn. Bravos de Paez. The regiment originally had 700 men :n 1 grenadier, 1 light and 6 line companies. Later two line companies were removed to from another unit and Vencedor had closer to 550 men.

The battalion wore a blue-jacket withred collars and red "barras" (a word which probably meant either shoulder straps or trousers stripes).

Bn. Voltigeros (Voltigeurs) : The black sheep unit of the Guard. The corps started life a-- part of the royalist, American-raised Numancia Regiment, passed to the Peruvians and Chileans, and finally joined Bolivar's Guard in 1822. Tough, brutal, but good fighters, the Voltigeros were disbanded after a mutiny in 1827. When the regiment first went over to the insurgents, it had about 750 men in 1 greandier, 1 light, and 6 line companies. It appears that the elites were later removed.

The Voltigeros wore a dark blue coat with sky blue collar and red "barras". They seem to have kept their old Peruvian standard for several years as a sort of regimental distinction. This flag was probably the San Martin model: diagonally divided into quarters, top and bottom white, right and left red. In the center, surrounded a green laurel wreath, a brown, multi-peaked mountain above which rises a yellow sun.

NOTE: For other standards, and uniform details not :et indicanted here, see under part II, INFANTRY.

Cavalry Regiment (sometimes known simply as the Guardia de Honor, although the name properly belonged to the whole corps): another one of the original Guard units. The regiment had one two-company squadron of 170 in 1215. Later another squadron seems to have been added. The regiment wore an incredible dress uniform: scarlet jacket, collar, cuffs, trousers. Gold chest frogging, Hungarian knots on sleeves and trousers, and piping on jacket, cellar, and white gloves. White belt running over the left shoulder (but beneath scarlet shoul-der straps) to a black cartridqe box slung at the right waist. knee boots with .old edge and tassels. Waist sash in alternating vertical stripes: yellow-blue-yellow-red-yellow-blue, etc. White fur with red bad and white plume rising from a yellow pompom. Silve sword, gold hilt, silver scabbard. The unit also carried pistols and carbines.

For horse equipment, spotted jaguarskin shabraque, gold stirrups, black girth straps, otherwise red reins and leather. The straps meeting at the chest were held together by a small, rectangular, tasseled red leather chest piece. The entire regiment rode "rucios", bright silver gray horses with darker gray manes and tails. These horses were said to be small, "but of very good race."

VI. PERUVIAN LEGION

Formed in 1821, "La Legion Peruana de la Guardia" came under Bolivar's command when he moved south. The Legion was supposed to be the premier force of Peruvians during the final struggles against the Spaniards. Its personnel was drawn from all races.

Unfortunately, the infantry compiled a mediocre combat record except at Ayacucho. Two battalions were planned, each with 8 150-man companies, 1 grenadier, 1 light and 6 line. However, it appears that only one battalion was completed, averaging 700 effectives.

The Legion infantry wore blue coats, red collars and cuffs, white piping and "barras", and probably white trousers and crossbelts. Boots were considered too uncomfortable, so sandals were substituted. Grenadiers had bearskins, light infantry British stovepipe shakos, and line infantry French shakos.

The Regiment of Hussars was supposed to have four squadrons, each with two 100-man companies. However, only two 100-man squadrons seem to have been active. After four name changes, including one period of being "cuirassiers" without cuirasses, the regiment was renamed the "Husares de Junin" for its prowess in that battle.

It is probable that the Hussars carried lances and swords and did not wear pelisses. Instead, their uniform seems to have been red jacket; medium blue collar, cuffs, and trousers; gold chest frogging, buttons, and piping on collars and cuffs; black boots and belts; and medium blue shako with red top band and pompom.

Finally, the Legion had a company of horse artillery with five 4-lb field pieces and one 4 1/2-in. howitzer. The company wore the uniforms of Britain's Royal Horse Artillery.

It would seem logical that the Legion carried the national flag designed by its first commander, the Marques de Torre Tagle. This consisted of three horizontal stripes, red-white-red, with a plain yellow sun in the center of the white stripe.

VII. CONCLUSION AND SOURCES

Several months after Ayacucho, Bolivar decreed a considerable reorganization of units and uniforms. However, since this did not take effect during the active campaigns against the Spaniards, it has not been detailed here.

Several months after Ayacucho, Bolivar decreed a considerable reorganization of units and uniforms. However, since this did not take effect during the active campaigns against the Spaniards, it has not been detailed here.

This article has been a survey to which South American experts could no doubt make corrections and additions. However, I hope that it has served as a.. introduction to a fascinating period. Bolivar's army may not have been Napoleon's 01d Guard, but it was colorful and filled with a special fervor, and did wage a long and successful war under extremely trying conditions.

Over 50 sources were consulted in preparing this article. Of these, the most useful were:

Associacion Amigos de la Biblioteca Nacional. Carabobo Para Todos.

Cochrane, Charles S. Journal of a Residence and Travels in Colombia During the Years 1823 and 1824.

De la Barra, F.P. ed. Coleccion Documental de la Independencia del Peru: VI (Asuntos Militares).

Duane, William. A Visit to Colombia in the Years 1822 and 1823.

Duarte Level, Lino. Cuadros de 1a Historia Military Civil de Venezuela (Biblioteca Ayacucho v.20)

Hasbrouck, Alfred. Foreign Legionaries in the Liberation of Spanish South America.

Knotel. "Venezuela 1820". Uniform Plate.

Miller, William. Memorias del General Miller (Biblioteca Ayacucho v. 26-27).

0'Connor, Francis B. Independencia Americana (Biblioteca Ayacucho v. 3).

Presidencia de 1a Reptablica (de Venezuela). Las Fuerzas Armadas de Venezuela en e1 Siglo XIX, I (La Independencia, 1810-1830).

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 84

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1985 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com