One should keep in mind that artillery, was first introduced as a siege weapon to simply destroy the walls of the almost impregnable castles found everywhere in the Middle Ayes (The middle ages period is defined as the period of European history from about A.D. 500 to 1500.). At first, weight was not of much concern since, in a siege, the artillerists had plenty of time to properly locate their weapons. Once in place the guns were usually not moved until the end of the siege. They were used in a purely static role.

A little later, artillery was used on a limited basis as a tactical weapon, mostly defensively, again in a static position. It was not that obvious to use artillery as a moving field weapon. (The first real usage of real field artillery pieces, according to Roquerol, pp. 6-7, can be credited to Charles the Temeraire against the Swiss in 1476. They were very heavy pieces when compared to their hitting power but nevertheless capable of following the slow, compact infantry formations of the period.)

However, once the need was recognized, constant attempts were made to reduce weight without reducing hitting power.

One of the main problems encountered was the fact that no clear cut difference existed between siege-artillery (which needed hitting power to destroy fortifications) and field artillery (which needed mobility to be an effective support to cavalry and infantry).

The real first practical field-artillery should be credited to the Swedish King Gustavus-Adolphus (1594-1632). The Swedes introduced a field-ordnance sufficiently light - especially 4-pounders - to follow the troops on the battlefield. Around the same time, in Holland, Maurice of Nassau had already foreseen the cooperation of artillery with the other arms. He used in the field small guns weighing around 900 pounds and called the the 12-pdr a field-gun. In Germany, great credit was given to the 6-pdr and even smaller guns because they were easy to handle on the battlefield. In France the term "field-pieces" (pieces de campagne) was used in the official reports to differentiate them from the siege and place artillery (pieces de batteries). However, during the XVIIth Century the new mission of artillery, i.e. that of the field-artillery, shown by the above forerunners (having as primary objective lightness and mobility) was not fully understood in the first place and, because of the importance of siege warfare (needing hitting power), the development of pure field-artillery was neglected. Consequently, guns remained heavy.

Furthermore, the greatest plague of artillery was that nothing was standard. Every one had his "secret" recipe to make a better gun. The diversity of gun models and calibers created incredible problems especially in the supply of ammunition. We lack the space to cover in depth the state of the art on artillery at that time, which, however, can be summarized as "suffering from lack of mobility and coherence created by the multiplicity of gun models and calibers."

THE VALLIERE'S SYSTEM

In France, de Valliere (Jean-Florent, 1667-1759) with the Ordinance of of 7 October 1732, introduced order in the equipment by eliminating the capricious diversity of calibers and models. He limited the gun calibers to five: 24, 16, 12, 8 and 4-pounders. However., only the manufacturing of the gun barrels was regulated and not the rest of the equipment, i.e. carriages, wagons, limbers, etc. The work of Valliere was consequently incomplete, but, still a significant improvement that gave birth to the first coherent artillery system.

HITTING POWER AND MOBILITY

De Valliere suffered from the siege warfare syndrome. He was certainly a very competent artillerist. He had participated to 60 sieges and only 10 battles and, apparently, did not recognized the different needs of siege artillery and field artillery. Worse, he made no attempt to differentiate their equipment. That was de Valliere's system main weakness. His reforms were done with a primary objective in mind: UNIFORMITY. That was achieved at the detrimental cost of mobility.

The short comings of de Valliere's system became quickly evident. The experience of the War of the Spanish Succession demonstrated that mobility was a primary requirement for field artillery on the battlefield. There started the long controversy between hitting power and mobility. (Ibid, p13.)

The controversy between de Valliere's son and Gribeauval was only one phase of it (see EEL 80) and did not stop there.

In EEL 81, (pp.37-39) we briefly quoted a little known source: General Allix "Systeme d'Artillerie de Campagne du General Allix,etc." in which the importance of lightness of field guns - i.e. MOBILITY - is shown by the numerous Napoleonic wars instances he presented. (Perhaps, the most surprising point was in challenging the importance of the 12 pounders.) It should be realized that Allix's book reports only a second phase, but not the last, of the controversy.

We can say that, in general, the necessity to lighten the field-equipment was accepted and the disagreement came from the different interpretations of what field artillery should do.

In France, the first step taken to introduce lighter field equipment was to imitate the Swedes. In 1742, the so-called Swedish light 4-pdr (a 1a Suedoise"), was introduced as the infantry battalion gun and introduced in the artillery park in 1748. The weight of theSwedish light 4-pdr was only 300 pounds only versus the 900 pounds of the heavier Valliere equivalent. However, the adequacy of the new gun was at best questonable after its performances fell short of expectation at Fontenoy. (Roquerol, pp. 20-21. The 4-pdr, the lightest gun of the Valliere’s system – weighing a total of 1220kg (2690 lbs) – required not less than 7 horses to be moved on a battlefield versus 4 for the Swedish gun. The lighter Swedish gun was not far in design (but slightly heavier) from the Gribeauval’s guns introduced in 1765. The Swedish 4-pdrs was still casted in the arsenal of Douay as last as 1792.)

THE LIECHTENSTIEN ANTI GRIBEAUVAL SYSTEMS

Both the Liechtenstein and Gribeauval systems were born from the imperative necessity to introduce in the Austrian and the French armies lighter ordnance! In both armies the heavier older guns were a failure on the battlefields. The Austrians, in 1742, at the battle of Czaslau, were the first ones to be unpleasantly surprised by the technical advance of the new Prussian artillery. (Lauerma, pp.11-12.)

The Prussians on the initiative of Frederick and von Holtzmann had worked on new field-artillery pieces only 16 calibers Long, etc. It resulted some practical lighter field-pieces, apparently, first introduced during the winter of 1742-43.

We already know the reaction of the Austrians (see EEL 81, p.11). In 1744, the Prince Joseph Wenzel von Liechtenstein, commander of the Austrian artillery (General-Direktor der Gesammten Land-Field und Haus-Artillery) with Colonel A nton Feuerstein von Feuersteinberg, started the design of the new field artillery Liechtenstein's system which was already used in the field as early as 1744. It was an excellent system. It was still in service at the Battle of Solferino in 1859:

The new system was standarized and von Holtzmann's radical lightening of the barrels introduced. Only 3 models of field-quns were kept: 3, 5 and 12 pounders. They were only 16 calibers long, as light as possible and weighted only 135 times that of the projectile. Yet, in spite of the lightness of the guns, relatively satisfactory firing was achieved. Gribeauval's reforms and system were covered in past issues of EEL (see EEL 81, 82). However, several points should be brought up. Gribeauval was the first, in France, to define field artillery and clearly separated it from the siege and place-artillery. (The Valliere’s system was perfectly adequate for siege and fortresses. It was kept as such by Gribeauval without major changes. Roquerol, p. 20. “At the beginning of the Wars of the Revolution…in addition to the Regulation guns (i.e. of the Gribeauval’s system) – and it was going to be so for several years to come- some guns of the Ordnance of 1732 (i.e. Valliere); which differed only by the exterior ornaments and a few other minor details from the equivalent siege and fortresses types of the 1765 System (i.e. Gribeauval), were used.”

He limited the field artillery calibers to 4, 8 and 12 pounders. He thought that the 4-pounder superior to the 3--pounder and easy to handle should be kept in service. the larger calibers were limited to the 12-pounder perfectly adequate to destroy houses if need arised.

THE YEAR XI ARTILLERY SYSTEM

A limit had to be set to lightness (even 1-prds were introduced). The Swedish 4-pounder had been found marginal to inadequate at the battle of Fontenoy. It was simply too light. Even Marshall de Saxe himself (de Saxe was the promotor of the light 1-pdr "amusette") reduced the number of 4-pounders (see Note 7)as too weak. This fact was confirmed by the Wars of the French Revolution. In foreign services, the 3-pdr was also found be too light and inadequate. It slowly disappeared and was replaced by heavier 6-pounders. (Ibid. p. 14. and Gribeauval Memoires quoted by Roquerol. One should not forget that one of the reasons for which Gribeauval fell in disgrace in 1757 was that he was opposed to the introduction in the French army of a new 3-pdr Swedish type gun “a la Rosting”.)

So, the logical evolution of the different artillery systems was the elimination of the smaller 3 and 4 pounders. That lead, in France, to the Year XI artillery system. (Ibid. p. 14 and Gassendi’s “Aides-Memoires, etc.”)

Bad comments have been made on the Year XI system. The 6-pounder, especially, has been reported to be of a poor design etc. Yet, it was designed on the same principles than the Gribeauval system: (1) length: 16 calibers, (2) windage: 2mm, etc. facts that, logically, should give identical perfomances. That is recognized by many French Napoleonic authorities and artillerists. General Allix is one of them. He does not say anything bad on the Year XI guns. On the contrary, he praises them for their light weight. In his opinion, the replacement of the weaker 4-pounder and of the heavier 8-pounder by the new lighter 6-pounder considerably improved the service and simplified the maintenance in the field. Furthermore, ammunition was lighter and there were now only two types of guns, two types of ammunitions, two types of spare carriages instead of the three types required by the Gribeauval system.

So, light weight and increased mobility were the main advantages of the Year XI system prefered by Allix to the new but heavier Vallee system which he simply considered too heavy to be practical. Mobility was Allix's main argument and to support it he gave a profusion of convincing examples from the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He further argued that to adopt the Vallee system was to go back to the Valliere's system.

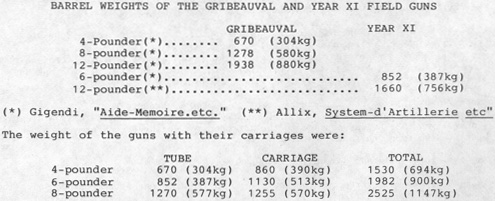

The significant weight differences are shown in the following table:

From the above, it's easy to see that the Year XI 6-pdr is midway between the 4 and 8-pdr and significantly lighter than the 8-pdr. Also, it appears that the carriage of the 6-pdr is almost as heavy as that of the 8-pdr and should of equal strength. we'll come back in our next issue on the Year XI 6-pounder since we don't have enough space here to complete our evaluation and complete our conclusions.

- Note: The same is true for the howitzers. The replacement of the Gribeauval 6-inch howitzer by the 24-pdr saved considerable weight. The most spectacular weight saving was in the ammunition. The same ammunition wagon could carry 75 24-pdr shells versus only 50 shells for the 6-inch Gribeauval howitzer. Allix was opposed to the 12-pdr (see EEL 81, pp. 38-39) which he found too heavy for a marginal range advantage and never available when needed because of poor mobility. For weight reasons he also preferred the Year XI 6-pdr over heavier Gribeauval 8-pdr.

At the present, my conclusions and thesis are simple. The Year XI System was simply the logical evolution of the Gribeauval System and was introduced:

- 1. to take advantage of its greater mobility because of its lighter weight.

2. to replace the weak 4-pdr with the more powerful 6-pdr.

3. to take advantage of the lighter 6-pdr ammunition, etc.

4. to simplify field servicing.

Increased mobility and efficiency was simply the measure we get from the above data. And that was not the exclusivity of the French.

Other main sources Beides Allix:

(Courtesy of George Nafziger)

Rouquerol, L’Artillerie Au Debut des Guerres de la Revolution, Berger-Levrault, Paris, 1898.

Lauerman, L’Artillerie de Campagne Francaise Pendant les Guerres de la revolution, Helsinki (Finland), 1956.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 84

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1985 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com