1. Introduction

This article is honestly entitled. I do not claim that it will be coherent or conclusive, but only that I will present the results of some investigations inspired by Jean Lochet's article "Some Comments and Considerations on French Tactics, Part VIII: On D'Erlon's Attack and Its Formations at Waterloo" [EEL 74:25-391. Like Lochet, I will be primarily concerned with the question of the formation or formations used by the French infantry in this attack; however, I will address myself also to the subsidiary issue of the order of the attacking forces in their initial dispositions, and during the attack. To some extent I will also be concerned with the formations and dispositions of the opposed Allies, but only as background information.

The "First Attack," is, of course, the Grand Attack, the attack whose defeat at the hand of Picton's 5th Division and the British Heavy Cavalry abruptly ended all French hopes of a quick and inexpensive victory. Naturally, D'Erlon's troops returned to the attack as soon as they had been rallied, eventually taking La Haie-Sainte, and decimating the Allied Left Wing with their artillery and smallarms fire. It is the first attack, however, with which I will be concerned here.

2. The Modern View of D'Erlon's Attack

2. The Modern View of D'Erlon's Attack

For modern historians of the Napoleonic Wars, D'Erlon's Attack is one of three classical examples of the French practice in the latter campaigns of conducting their attacks in huge columns. The other two examples usually cited are MacDonald's Attack at Wagram [cf. Chandler 1966:346] and the attack of the Ve Corps at Albuera [cf. Hughes 1974: chapter 6]. This is not to say that these are the only examples possible, but only that they are the three with pride of place.

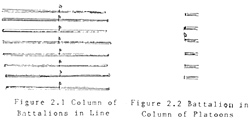

In the modern view, D'Erlon formed his troops for the attack as follows: each of his four Divisions formed a single column, with column meaning here not simply 'force', but 'integrated formation emphasizing depth'. Within each of these Divisional strength columns, the constituent battalions were actually deployed in line, with the battalion lines following each other in succession [see figure 2.11. Note that the formal definition of a column in this era was that it was made up of identically formed, similarly sized subunits, one behind another, e.g., a column of platoons would consist of a series of platoons, all deployed, one behind another [see figure 2.2].

Consequently, D'Erlon's "Columns" were true columns: all the battalions were deployed, they were all battalions alike, and they were arranged one behind another. What is unusual, and perhaps unprecedented, is that the fact that the columns were comprised of deployed battalions. Certainly, the French infantry regulation [Reglement 1791] did not anticipate that columns would be made up of deployed battalions, or, actually, of any unit wider than a division, i.e., a pair of platoons (pelotons), though it did anticipate that columns made up of large numbers of battalion columns, one behind another, would be used regularly in maneuvering.

Beyond this there is some disagreement. Some authorities indicate that some of the columns, usually those on the flanks, were broken down into smaller columns similarly formed but of brigade strength only - during the course of the attack, or even ab initio.

A further source of disagreement is the motivation for the unusual characteristics of the formations. Some speculate that it arose through error or confusion. Houssaye [1921:347n3} goes so far as to speculate that the error arose from a specific garbling in the orders:

- "There is a presumption that this order was given by the comte d'Erlon, who had the immediate command of the Ier corps d'armee.

"It can also be supposed that the aide de camp, in transmitting the order, confused colonne de division (which is to say, column by battalions closed up in masse) and colonne par division (~hich is to say, column by paired companies, at half or full intervals )."

Becke makes a similar comment [1914:2.62-3] with slightly different details, and attributes the speculation to Grouard [either 1904 or 19071. These terminological speculation are somewhat ingenious, since the terminology supposed is unusual and never justified, and since they have as a collary that there was either a sufficient precedent for the formation or widespread stupidity among the French general officers. More to the point are speculations that the formation was intended to combine the maneuverability and control of a column with the firepower of the line. Such speculations, however, take the views of the firepower school of Napoleonic tactics for granted, and leave us with the uncomfortable impression that d'Erlon used an untried and experimental formation in what he must have known was a crucial attack.

There is a tendency for authors describing d'Erlon's formation to dwell on the width and depth of the columns in files and ranks. While this must originally have been intended simply to give the reader some idea of the scale of the columns, it is possible that some recent authors have been under the impression that these figures conveyed some essential information about the formation of the columns, rather than depicting the natural outcome of forming a column from successive deployed battalions.

If the battalions in question have an average strength of 500 men, and form line in three ranks, then it is inevitable that columns formed as d'Erlon formed his will have a width of approximately 170 files and a depth of precisely three times as many ranks as there are battalions in the column; 24 ranks in the case of most of d'Erlon's columns, since three of his Divisions had 8 battalions each, and the fourth had 9. This does not, however, mean that d'Erlon adopted the formation he did with a view toward forming a solid mass 170 files wide and 24 ranks deep.

3. Evolution of the Modern View

What I have been calling the modern view has not always been the accepted view. To my knowledge, it appears in its earliest form in Charras's Histoire de la campagne de 1815, first published in 1857. Charras's report is as follows [Charras 1907:280-2811:

- "... Napoleon ... had Ney told to arrange the four Division of the 1st Corps in as many columns in echelons, the left in front Fautant de colonnes par echelons, la gauche en avant], in order to seize La Haie-Sainte, gain control of the valley, and reach the plateau.

"Whether through some misunderstanding in the transmission of he orders, or through some aberration of the Marshal or of d'Erlon, the Divisions were each formed in a solid masse [read either 'mass' or 'close column', JEK], consisting of a series of deployed battalions, each battalion five paces behind its predecessor.

"The first echelon, the one on the left, was made up of the brigade Bourgeois, of Alix's [1st] Division, the Division's other brigade, that of Quiot, being told off to attack La Haie-Sainte. Donzelot's [2nd] Division formed the second echelon; that of Marcognet [3rd], the third; that of Durutte [4th], the fourth.

"The interval between echelons was 400 paces; each Division had 8 battalions, except Donzelot's [2nd], which had 9. 3a

"These novel columns [etranges colonnes] presented, then, here 12 ranks, there 24 or 27 ranks of depth [i.e., 3 ranks x 4, 8, or 9 battalions], with a front varying from 150 to 200 men [i.e., for battalions of 450 to 600 men], depending on the strength of the battalions."

Charras's views on the formations are further elucidated in a footnote to the preceding, in which he reveals his source and takes the opportunity to twit his rival, the historian and politician Thiers [Charras 1907:281n2]:

- "This singular formation used by d'Erlon's corps has been presented

to date in a rather inaccurate fashion by both French and foreign historians. We are indebted to the kindness of a general who was a senior officer in d'Erlon's corps for the details above. In a remarkable note that he sent us, we read that the chef de bataillon of the last battalion in Durutte's [4th] Division had wheeled his troop into column by divisions, just about to form a close column [(prete a former le carre), and that Durutte, seeing this action, had instructed him to put himself in line, since those had been the orders.

"M. Thiers describes d'Erlon's formations as we (to, no doubt on our authority [i.e., in en earlier edition, .JEK]. But. he concludes his version with the words 'These four Divisions, forming thus four dense and deep columns, advanced even with each other, leaving between themselves 300 paces.' What? Echelons level with each other!"

When Charras says that d'Erlon was to advance la gauche en avant ['left in front'], it is not clear whether he means this in the technical sense, i.e., that each Division is to have its leftmost units leading, or whether he simply means that the leftmost Division is to advance before the next one to the right, and so on. Ills footnote seems to suggest the latter. In either event, Charras's statement misrepresents Napoleon's actual order, as quoted by Ropes [1893:388], based on the version published in Documents inedits [1840:53]. The actual order reads, in part:

- "... the comte d'Erlon will begin the attack by advancing his leftmost Division, and supporting it, according to circumstances, with the [other] Divisions of the Ist Corps."

The note has a penciled addition in the hand of Ney, saying:

- "The comte d'Erlon will understand that it is by the left that the attack is to begin, rather than the right. Communicate this new disposition to the general en chef Reille."

That is, the order simply says that the leftmost Division will attack first, with the others in support in any convenient fashion.

It is unfortunate that Charras's source remains anonymous, and that Charras does not give us the precise language of his source, but only some extracts. These failings are somewhat repaired by the treatment in Houssaye's 1815 - Waterloo, first published in 1893. Houssaye's version reads [1921: 347-348]:

- "... The four Divisions marched in echelons by the left, with an interval of 400 meters between them. Allix's [1st] Division, commanded by general Quiot, formed the first echelon; Donzelot's [2nd], the second; Marcognet's [3rd], the third; Durutte's [4th], the fourth. Ney and d'Erlon led the attack.

"Instead of ranging these troops in columns of attack, i.e., in columns of battalions by division at half or full interval, a tactical arrangement as favorable to rapid deployment as to forming square, each echelon was made up of battalions deployed and closed up on each other en masse [read 'in close column', JEK]. The Divisions of Allix [1st], Donzelot [2nd], Marcognet [3rd], and Durutte [4th], therefore, presented to the eye an appearence of four compact phalanxes, each with a front of 160 to 200 files, and a depth of 24 men [i.e., the battalions were from 480 to 600 men strong, and were formed in lines 3 ranks deep, JEK]. Who had prescribed such a formation, dangerous in any event, and particularly so in that uneven terrain? Ney, or, rather, d'Erlon, who commanded the 1st Corps. In any case, it was not the Emperor, for his order of 11 o'clock [that quoted above, JEK] says nothing of the sort, nothing even of an attack in echelons. ...

As sources for his account, Houssaye cites:

- 1) Souvenirs d'un ex-officier, 285-286.

2) Nauduit. Derniers fours .. , 1I, 293.

3) "Note du genctral Schmitz [one of Donzelot's brigadiers in the 2nd Division]," communicated by commandant Schmitz [presumably a de scendant].

4) "Relation de Durutte," in Sentinelle de 1'Armee, 8 March 1838.

5) "Notes de Durutte," communicated by commandant Durutte [presumably a descendant], officer of the Belgian Army.

Unfortunately, I have access to the text of only one of Houssaye's sources, the Souvenirs d'un ex-officier. The ex-officier was a Swiss pastor named Martin, who had in 1815 been a lieutenant in the 45e de ligne. His version follows [Martin 1867:285-286]:

- "When it was believed that the British were sufficiently shaken

by the fire of our guns, the four Divisions of d'Erlon were formed in separate columns. The third, that of Marcognet [3rd Division], of which our regiment [45e de ligne] was part, was to march, like the others, by deployed battalions; an odd arrangement [disposition Atrange] and one which was to cost us dear, for we were unable to form squares to defend ourselves against cavalry, and the enemy artillery could play upon us as we stood arrayed 20 [sic] ranks deep. To whom did the 1st Corps owe this ill-conceived formation, one of the causes of its failure, perhaps the principal one? No one knows."

Martin's memoirs continue with a sketch of the advance, in which he reports that they gained the hedge, evicting some "British troops" from a sunken road [either Pack's British 9th Brigade, or Bijlandt's Dutch-Belgian Brigade, with a stronger likelihood of him meaning the latter], and were getting back into order when they were caught unaware by the British cavalry [Ponsonby's 2nd "Union" Brigade]. He speaks of the rout, and of the later return of the Division to a desultory fight with the British lines, but offers rather little in the way of detail for these later events. Moreover, it is unfortunately clear from elsewhere in his book that he was familiar with both Charras's arid Thiers's accounts of the battle, so that we cannot be absolutely certain that he is an independent source.

At this point I have completed my survey of the accepted modern view of d'Erlon's formations. To emphasize that it is a partial survey, intended primarily to summarize the view and the evidence in its favor. I have not yet tried to deal with the details of the advance, or detachments made during it; these have been surveyed recently by Lochet in his article in EEL 74, for those who desire to refresh their memory of them, or can be examined at first hand in Charras, Houssaye, or one of the many modern summaries for the popular market, e.g., Chalfont or Chandler 1981. I draw the reader's attention particularly to the unfortunate fact that I have been unable to present any first-hand account of the advance favoring the modern view, other than the somewhat suspect version of Martin. I believe, nevertheless, that we can operate on the reasonable hypothesis that the sources cited by Charras (albeit anonymously) and Houssaye support the modern view as ;it least the initial formation, though we may legitimately suspect that, this formation may not hove remained in use throughout he attack.

4. Early Confusion

The modern view is now so firmly entrenched that it is easy to forget, or overlook, the fact that it was once largely unknown to historians. At first it was, at best, simply one of the possibilities. The former uncertainty, attested by Charras above, may be exemplified with an extract from van Loben-Sels's Precis de la campagne de 1815, a Dutch work published [in French] in 1849 [327-328]:

- "... It appears beyond doubt that the Divisions of the French 1st Corps were deployed in as many columns of attack as there were Divisions, but one asks in vain how these columns were aranged. Taking it that each one comprised a Division, it is still not clear on what frontage each was formed, or even whether the flanks were protected [si les flancs en etaient garnis]. If one is guided by the various sources and maps, one would be constrained to believe that each column was on a front of a single company, and at a depth of eight battalions. We will not make a definite decision on whether such formations were, in fact, used, but it is certain that they would have been the least appropriate for the attack that these Divisions [rendering colonnes] might have adopted. ... French authors not having revealed a thing on the subject, those of the opposed nations may perhaps be allowed to submit as a first approximation that they were presented with a view of columns with a depth more than ordinary, but not amounting, in fact, to more than three or four battalions at full interval [ceux des nations 2pposees se sont peut-etre laisse entrainer par le premier coup d'oei qui leur faisait voir des colonises- d'une profondeur plus qu'ordinaire mais qui ne contenaient en effet que 3 ou 4 bataillons avec de Brands intervalles]."

To this statement van L8ben-Sels adds a footnote, to the effect that "The official report of the 2nd Netherlands Division [containing the Brigade Bijlandt], edited by Colonel van Zuylen van Nyeveld, speaks of this attack in the terms 'one regiment succeeded by another' but offers no explanation of the formation of the columns."

The report of the 2nd Division is cited in full in de Bas [3.289-353], from which the following is extracted:

- "The entire 1st brigade (van Bijlandt) and the artillery of the right wing conducted a retrograde movement at noon, in order not to block the British artillery [Rogers's battery] behind them and in order not to be exposed so much to the play of the enemy's artillery. The aforesaid troops crossed the sunken road and formed themselves on its north side, in the same order of battle as before, supported to the right and the left by some English and Scots troops, the artillery in line with that of the British.

"The 5th Battalion of Landwehr received the order to go into reserve, and placed itself in the second line, which was made up of the English and Scots troops.

"After this fire, extremely violent, had lasted a full hour [een groot uur], with many casualties on both sides, the masses advanced about two o'clock...

"To crush the center of our line, Bonaparte had chosen the 1st corps, which alone had not been involved in the earlier affairs. Regiments succeeded regiments in the attack on La Haie-Sainte, and each foot of ground was, at the cost of torrents of blood, defended, taken, and retaken; bodies strewed the ground, side by side.

"Meanwhile, three attack columns, under the command of the comte d'Erlon, advanced against our position, the 103e [sic] regiment in the lead [i.e., the 105e]. ..."

It can be seen that, in the context, the quoted phrase has little or no significance.

5. Deployment of the Opposing Forces

In succeeding sections we will be examining the interactions of the French and their opponents in some detail, in order to determine whether there is eyewitness evidence that the four French columns were subdivided into a larger number of small columns in the course of their advance. As an aid to the reader in the course of this discussion, we present in this section a description of the deployment of the forces at the outset of the attack.

There has been some controversy regarding the initial deploy ment of the French. French secondary sources suggest that d'Erlon's Divisions were arranged from the French left to the French right in the order 1st Division (Alix), 2nd Division (Donzelot), 3rd Division (Marcognet), 4th Division (Durutte). This is the order, for example, given by both Charras and Houssaye [see extracts in section 21. While I have not been able to verify this in a French primary source, there seems to be no reason to doubt it. On the other hand, British secondary sources in the early part of the 19th Century are fairly consistant in making the order 2nd, 1st, 3rd, 4th. See, for example, Batty 1820:80-81 or Siborne 1895:356-357.

Even Becke's revised edition of 1914 [2.61] retains this order. As I hope to show in the next section, there is basis for British obstinacy on this point, namely that they encountered troops from Alix's Division to the right of others evidently belonging to Donzelot's 2nd Division. We will pass over this difficulty until the time comes to account for it [sections 5 and 7].

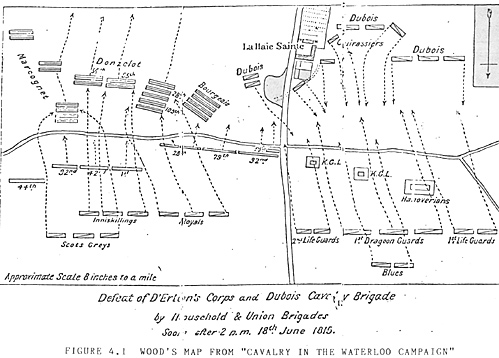

It is worth observing that British writers' attempts to adopt the French-attested order have not always been completely successful. As Lochet observed in EEL 74:31, 35, the Chalfont volume adopts the correct version in its text [1979:96, 100], but retains the incorrect version in its maps [87, 145]. Similarly, an examination of the sketch map presented by Wood in his 1895 Cavalry in the Waterloo Campaign [see figure 4.1] reveals that the labeling of French Divisional and brigade commanders is proper for the French-attested order 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, as is the patterning in the number of battalions depicted in each Division (Donzelot's 2nd Division was the only Division to have 9 battalions, as properly depicted in the sketch map).

However, Wood also chooses to identify some of the French regiments as well, and here he seems to assume the British attested order 2nd, 1st, 3rd, 4th, with the unfortunate consequence that what he calls Donzelot's Division has the regiments belonging to Alix.

FIGURE 4.1 WOOD'S MAP FROM "CAVALRY IN THE WATERLOO CAMPAIGN"

FIGURE 4.1 WOOD'S MAP FROM "CAVALRY IN THE WATERLOO CAMPAIGN"

Wood's error is understandable when it it is realized that he was heavily dependent upon H.T. Siborne's Waterloo Letters for his details. H.T. Siborne was the son of William Siborne, the author of The Waterloo Campaign. The latter began his career as an authority on Waterloo by engaging in the construction of a "Model" or diorama of the battle.

In the end he constructed several dioramas, and authored the history which has come to be essentially the canonical version of the battle in the English language. In the course of his research, "he was authorised by the General Commanding-in-Chief - Lord Hill - to issue a Circular Letter to the several surviving Officers of the Battle who might be in a position to afford him the information necessary for the completion of his undertaking" [H.T. Siborne 1891:v]. The Waterloo Letters are a selection of the responses to this circular, together with various other letters arising from Siborne's later correspondance on the subject of Waterloo, extracted and published by the son.

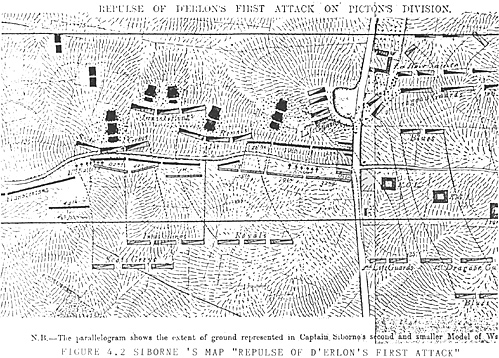

Naturally, the views on the French deployment present in the Letters volume, and in its maps, based on Siborne's dioramas, are those of Siborne. In fact, Wood's sketch map is a revision of Letters figure "Repulse of D'Erlon's First Attack on Picton's Division" [see figure 4.2], which is itself based on "Captain [William] Siborne's second and smaller Model of Waterloo" [II.T. Siborne 1891: opposite p. 381. Wood's version eliminates the bulk of the terrain detail and the second positions of the units, places the French troops in battalion lines in accord with French authorities, and labels the French units in accord with these same authorities, though, not, as we have seen, with entire success.

The presentation of figures 4.1 and 4.2 introduces the subject of the deployment of the British and Dutch forces. The arrangement depicted in figure 4.4 is described by Siborne 1891:398-399 as follows:

- "The 28th, 32nd, and 79th Regiments of Kempt's [8th] Brigade, when deployed, occupied a Line parallel to, and about fifty yards distant from, the hedge along the Wavre road, its Right resting on a high bank lining the Charleroi road, and its Left terminating at a point in rear of that part of the havre road which begins to incline for a short distance towards the left rear. In their right front, immediately overlooking the intersection of the Charleroi and Wavre roads, stood (as before stated) the Reserve of the 1st Battalion 95th Rifles; they had two Companies, under Major Leach, posted in the Sand Pit adjoining the left of the Charleroi road; and one Company, under Captain Johnston, at the hedge on the Knoll in rear of the Sand Pit. Their Commanding Officer Colonel Sir Andrew Barnard, and Lieutenant Colonel Cameron, were with these Advanced Companies, watching the Enemy's movements.

"Pack's Line [9th Brigade] was in left rear of Kempt's [8th] Brigade, and about 150 yards distant from the Wavre road. its Left rested upon the Knoll between the Wavre road and a small coppice on the reverse slope of the position; but the Centre and Right extended across a considerable hollow which occurs on the right of that coppice. The front of the interval betwen the two Brigades became, after the retreat of the Dutch-Belgians, completely exposed and uncovered."

The position of van Bijlandt's Dutch-Belgian brigade [1st Brigade/2nd Netherlands Division] would have been directly to the left of Kempt's 8th British Brigade, with its battery [Bijleveld's] in its front, and the 5th Landwehr Battalion behind, in a second line [see above, section 3].

FIGURE 4.2 SIBORNE 'S MAP "REPULSE OF D'ERLON'S FIRST ATTACK"

FIGURE 4.2 SIBORNE 'S MAP "REPULSE OF D'ERLON'S FIRST ATTACK"

Note that figure 4.2 shows Pack's 9th Brigade further forward than it was at first. Initially it was where Wood places it in figure 4.1. The British cavalry was to the rear of the infantry. Ponsonby's 2nd "Union" Brigade was behind the 8th and 9th Brigades, in the order left to right Scots Greys [2nd Dragoons], Inniskillings [6th Dragoons], Royals [1st Dragoons]. The Scots Greys were slightly in rear of the Inniskillings, and were intended as the brigade reserve. Somerset's 1st "Household" Brigade was about even with Ponsonby's 2nd Brigade, but was across the roai to the east, in rear of Ompteda's 2nd KGL Brigade and Kielmannsegge's 1st Hanoverian Brigade. The brigade was in two lines, of which the first comprised, from left to right, the 2nd Life Guards, the 1st Dragoon Guards, and the 1st Life Guards, while the second line consisted of the Horse Guards Blue, or Blues. The 1st Brigade enter into the account here at all only because they formed the right wing of the same attack in which the 2nd Brigade overran d'Erlon's Divisions, and because in the process of defeating the French cuirassiers opposed to them, they crossed the Charleroi road behind La haieSainte, and impinged upon Kempt's 8th Brigade and the French troops opposed to that brigade.

This concludes the discussion of the initial deployments. In succeding sections I recommend that the reader refer back as often as necessary to figures 4.1 and 4.2, since a proper appreciation of the relative positions of the various units is essential to comprehension.

To be continued

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 78

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com