I have started to write about the FOREIGN REGIMENTS IN FRENCH

SERVICE in the COURIER back in 1975. Such regiments should be

distinguished from other foreign contingents like the Saxons and

Westphalians etc. which combatted willingly or unwillingly under their

colors as allies.

I have started to write about the FOREIGN REGIMENTS IN FRENCH

SERVICE in the COURIER back in 1975. Such regiments should be

distinguished from other foreign contingents like the Saxons and

Westphalians etc. which combatted willingly or unwillingly under their

colors as allies.

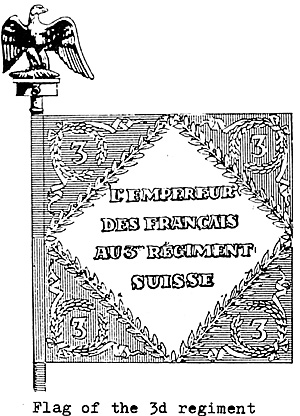

Flag of the 3d regiment The other side of the flag had the following inscription

VALEUR

ET DISCIPLINE

1er BATAILLON

The regiments and units covered by this series of articles were part of the French Army. Some were good or even elite troops, some were not so good and some frankly bad like the Regiment d'Isembourg.

The Swiss regiments were certainly the best foreign units in French service. After the battle of the Berizina, Napoleon said about them: "Brave Swiss you all deserve the cross". According to Rigo, LE PLUMET plate 29, they were only 300 survivors after the Russian campaign.... They were 12000 when they crossed the Niemen some five month earlier.

Swiss troops were nothing new in the French Army. The COMPANY OF THE HUNDRED SWISS was raised in the reign of Charles VIII of France(1483-1498) as guards for the King's person and his palace. These elite troops performed their duty during almost four century until the end of the reign of Charles X in 1830, with, of course, the interruption of the French Revolution and the First Empire.

During the Revolution several Demi-Brigade of Swiss infantry were raised. They served especially in Italy. In 1803, by the Acte de Mediation, Bonaparte, First Consul, had reorganized the Helvetic Republic and concluded a alliance treaty whereby the French Republic agreed to defend Switzerland. On the same year, Bonaparte revived the tradition of the Capitulation initiated in 1516 between the French Monarchy and Switzerland.

The new capitulation was signed in Fribourg on 27 September, 1803 by General Ney for France and some famous names of the Swiss military history like Loius d'Afry, Charles Pfiffer, Francois Andermatt and Amedee de Muralt, all members of the Swiss Diet.

A Capitulation, or Capitulum, was an honorable agreement whereby any foreign power could draw for one reason or another some troops from Switzerland. Between 1444 and the second half of the 39th Century over two millions of Swiss were to serve several countries.

The Capitulam was in fact a treaty of alliance concluded with the approval of the Swiss Diet. It specified the clauses acceptable to both parties i.e. recruting methods, conditions of service, supply of arms, rate of pay etc.. For instance, in 1803, the rate of pay was fixed at 1.2 francs 'for a fusilier and 1.25 francs for a grenadiers. Switzerland was also to make good for deserters in the first two years. Fieffe, LES TROUPES ETRANGERES AU SERVICE DE LA FRANCE (1854) The Capitulum of 1803 had also provision for the recall of all the other Swiss troops in foreign service other than France on the simple request of France.

In 1810, Napoleon asked for the withdrawal of the Swiss troops still in the service of Spain. They were six Swiss regiments in Spanish Service in 1808, and Napoleon tried to have them serve in the French Army in Spain certainly by bending a little the Capitulation of 1803. He only partially succeeded. The Swiss regiments de Preux and Reding until then in Spanish service are found in the battle order of General Dupont at Baylen. A great deal of confusion took place. A great number of Swiss soldiers who had been in Spain for many years could not bring themselves to fight their friends the Spanish, yet, Thiers in HISTORY OF THE CONSULAT AND OF THE EMPIRE reports that many Swiss deserted the other Swiss regiments in Spanish service to join the French Army. It is once more a confuse subject and worth a special study.

It is very unfair to call the Swiss mercenaries. They are very touchy about it see Jean Nicolier COLLECTING TOY SOLDIERS) It is quite true that we are dealing here with complete units and not individuals. Furthermore their achievements in Foreign services was often behind the call of duty such as the sacrifice of the Swiss Guards in the Tuilleries in 1793.

Until 1805, because of the relative security given by the presence of the Grande Armee at Boulogne the organization of the Swiss regiments was not activelly pursued. So far, only the 1st Swiss regiment was organized from the remains of the three Half-Brigades previously in the Service of the Republic. The 1st Swiss regiment was raised by the decree of January 10, 1805 and organized on March 15, 1805. It included a company of artillery (compagnie d'artillerie Suisse) recruited on April 19, 1803.

Buttons: Gold or brass.

Buttons: Gold or brass.

It is of interst to note that the 1st Swiss regiment went, at least on paper to the service of the Kingdom of Naples, by an executive order of October 27, 1807. This move was considered as nil since the transfer had not been ratified by the Napolitan government. The 1st Swiss was officially reintegrated in French service on October 1st, 1808.

The company of Swiss artillery created on April 19, 1803 was attached to the 1st Swiss regiment on April 1st, 1806. Latter, by a decree of December 10, 1811, the three other Swiss regiments were to receive a company of artillery.

According to Fieffe, each artillery company included two 3-pounders (very likely captured Austrian guns), 3 ammunition waggons, a campaign forge, 2 ammunition waggons for cartridges, 2 ammunition waggons for the bread and 1 ambulance waggon.

The decree of August 12, 1805 created the 2nd, 3d and 4th Swiss regiments. The recruiting went on quickly. Napoleon wrote to the Minister of War:11I see with pleasure that you are showing a special in the organization of the Swiss regiments. It is of the upmost importance. I don't want money to be an issue. I need these regiments for the defense of the coasts."

Napoleon had learned to appreciate the Swiss in Italy. He was right the Swiss were to serve him well until 1814.

In 1814, after the abdication of Napoleon the four Swiss regiments were kept by Louis XVIII. In 1815, when Napoleon came back to power, the Swiss government to the latest agreement with the King of France decided not to serve Napoleon. The Swiss were disbanded, however some 730 men were persuaded to return to Napoleon's service and were incorporated in a battalion called the second Swiss regiment. It was part of Vandamme's III Corps and almost wiped out at Wavre.

According to LES AIGLES IMPERIALES 1804-1815, under the provision of the decree of 1804 the Swiss Demi-brigade, on a temporary basis, should have received an Eagle. The inscriptions on the flag was: L'EMPEREUR DES FRANCAIS A LA...DEMI-BRIGADE HELVETIQUE.

It is very doubtful that the provision was executed because of the reorganization of the Swiss units.

According to the Regulation on flags issued on September 12, 1804, each battalion of each regiment should have received an Eagle with the 1804 pattern flag. In spite of the Ordinance, it appears that the Swiss regiments received only one Eagle per regiment.

The inventory of the Eagles ordered in 1812 gives the following data.

- 1st Regiment. One Eagle given by the Emperor at the creation of the

regiment

2nd Regiment. One Eagl; given in Avignon on March 19, 1807.

3d Regiment. One Eagle given by General Morlot in 1807.

4th Regiment. One Eagle given at the creation of the regiment.

The flag was of the 1804 pattern and is shown on the next page. Le PLUMET plate describe the flag and the history of the 3d Swiss. It is a very nice plate and I recommend to purchase it.

It is interesting to note here that the Swiss regiments were the only French units with the Imperial Guard to enter Russia with the 1804 flags. All the other units of the French Army had received the new 1812 pattern flag. The four Eagles of the Swiss regiments were brought back from Russia in spite of the terrible losses ... The 3d Swiss had only 80 survivors...

Perhaps it is time to say here that in spite of the fact that two Swiss battalions were at Baylen, the 3d battalion of the 4th and the 1st battalion of the 3d no Eagles were lost. Somehow the Eagle of the 3d (The Eagles were always with the 1st battalion) was not captured. ref. LES AIGLES IMPERIALES, page 255.

Apparently, the 1st Swiss remained in Italy in 1805 and at least part of the regiment was at Maida were it substained. sensible casualties. A few days after the battle of Maida, the 1st and 4th battalions of the 1st Swiss had an encounter(not of the third kind) with the Calabrese insurgent. Fieffe in LES TROUPES ETRANGERES AU SERVICE DE LA FRANCE --page 210, vol.2, reports that Reynier had received the order to go to Cassano and wait in that town for reinforcements under Masena. The Swiss because of their red uniforms had been already mistaken by the Calabreses for British infantry. That gave the idea of an operation against the Calabreses. The two Swiss battalions under the cover of the night came out of Cassano and by along detour came at dawn in the front of a village occupied by a strong force of insurgents. The latters saw the Swiss with their red uniforms coming from the opposite direction of the French camp tought that they were British troops landed during the night ... They came out of the village in great number to greet their friends the British ... They were received by a very efficient volley followed by a bayonet charge. The casualties were high for the Calabreses, some 1000 dead and wounded.

The uniforms were very similar to the French uniforms. The red was substituted for the

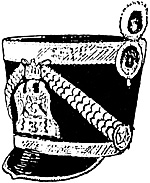

blue. The front cover represents the lieutenant Eagle-bearer of the 3d Swiss in 1812 uniform. The coat is red and the white breeches are covered by grey overalls. The grey greatcoat is wrapped around the shoulder. The shako identical to the one shown next page is protected by'a black oilskin. The coats shown in the next page are for the 3d Swiss. Please note that the cuffs should have been white according to the official regulations.

The uniforms were very similar to the French uniforms. The red was substituted for the

blue. The front cover represents the lieutenant Eagle-bearer of the 3d Swiss in 1812 uniform. The coat is red and the white breeches are covered by grey overalls. The grey greatcoat is wrapped around the shoulder. The shako identical to the one shown next page is protected by'a black oilskin. The coats shown in the next page are for the 3d Swiss. Please note that the cuffs should have been white according to the official regulations.

SHAKO of officer 1812: It appears that the shako remained the same since 1807 with the "cocarde" on the right.

For once, everybody agrees on the uniforms. The following is from Malibran GUIDE A LIUSAGE DES ARTISTES ET DES COSTUMIERS(description of French army uniforms from 1780 to 1848) pages 325 and 326.

The facings are given next page with the drawings. The officers of voltigeurs, of the 3d Swiss had a bearskin with gold cord, they were equipped with a carbine and an ammunition pouch as per the regulations of March 14, 1804 and September 19, 1805 like all the officers of voltigeurs of the infantry regiments.

The officers had also wore a breast

plate in gilded brass with a silver coat

of arms showing the Imperial Eagle

surrounded by the coats of arms of the Swiss Cantons.

The officers had also wore a breast

plate in gilded brass with a silver coat

of arms showing the Imperial Eagle

surrounded by the coats of arms of the Swiss Cantons.

The grenadiers had a bearskin even in 1812, with a crowned eagle of brass. The cords were white and the plume also white with a red topping. The chin scales were of brass. The sappers had also a bearskin but without the crowned eagle.

The epaulettes were white for the grenadiers, with yellow franges for the sappers and the voltigeurs have apparently chamois epaulettes. Gilded breast plate until 1812. On January 19, 1812 the above worn by the officers. was changed as it follows: grenadiers red epaulettes, fusiliers red with a pipping of the facing color, voltigeurs chamois.. The bearskin of the grenadiers is also different. the front plate is now a grenade with the regiment number embossed in the bomb. The plume is now red and the cords are also red.

Since October 7, 1807 the voltigeurs and the fusiliers do not have the sabre-briquet. This sabre is worn by the non-commissioned officers, the corporals, the grenadiers and the drummers.

According to the Capitulation of 1803, each regiment includes four battalions. Each battalions is of 1 company of grenadiers and 8 companies of fusiliers. In 1807, a company of voltigeurs is added to each battalions.

Uniform

The Swiss Regiments had the following

- 1st Regiment:Yellow cuffs, collar, and lapels, blue trimming.

2nd Regiment: Blue cuffs, collar and lapels, yellow trimming.

3d Regiment: Black cuffs, collar and lapels, white trimming

4th Regiment:Light blue cuffs, collar and lapels, black trimming.

Bibliography

Jean Nicolier COLLECTING TOY SOLDIERS

Fieffe, LES TROUPES ETRANGERES AU SERVICE DE LA FRANCE

Jean Regnault, LES AIGLES IMPERIALES, 1804-1815.

LE PLUMET PLATES.

MALIBRAN, GUIDE A L'USAGE DES ARTISTES ET COSTUMIERS

Funckens,L'UNIFORME ET LES ARMES DES SOLDATS DU PREMIER EMPIRE.

Volume 2.

Thiers, HISTORY OF THE CONSULAT AND THE EMPIRE.

Misc. notes etc.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 26

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1978 by Jean Lochet

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com