The 39th Regiment of United States Infantry was the product

of the Congress trying to field adequate regiments during the conflict known as the War of 1912. Recruiting was difficult and men so hard to organize that Congress had been forced to reorganize the Army several times by the year 1812.

The 39th Regiment of United States Infantry was the product

of the Congress trying to field adequate regiments during the conflict known as the War of 1912. Recruiting was difficult and men so hard to organize that Congress had been forced to reorganize the Army several times by the year 1812.

As of June of that year regulars could only enlist for five years tour of duty. However, by late that year, newcomers could enlist for the duration of the war. State Militias whichh offered shorter tours of duty, competed with the National Government for men. The shorter tours naturally drew more men to the State ranks.

In January of 1813, Congress created twenty new infantry regiments in which prospective recruits could enlist for just one ear. Nineteen of them were raised, being numbered the 26th through the 44th regiments. Thus the 39th was organized by this act on January 29th, 1813; and though originally raised for one year's service, the term was greatly extended in late 1813.

The 39th was organized in Knoxville, Tennesse and the surrounding areas. John Williams was appointed Colonel of the regiment on June 18th, 1813, and served until the end of his military duty as the unit's commander, which concluded with the 39th being disbanded on May 17th, 1815. The Lieutenant Colonel of the regiment was Thomas H. Renton who served from June 18th, 1813 until May 17th, 1815. The Majors of the regiment were Uriah Blue, William Peacock and Lemuel Purnell Montgomery, an important young lawyer who was killed in the battle at Horseshoe Bend. The county of Montgomery in Alabama is named for him. One source states that he was the son of General Richard Montgomery killed in the assault on Quebec in December of 1775.

Colonel John Williams was given the task of recruiting and organizing the regiment. His success with the East Tennessee Militia he had command ed previously was an important factor in his commission. Many of his ex-volunteers, out of loyalty to their former commander, re-enlisted in the twelve month regular army. One method of recruiting was to send a squad or two into a town and begin drilling. This would immediately attract a crowd, Which in turn would draw even more people.

After a time the drill ceased, and the drummer would set his instrument upon the ground head up. The ranking officer or non-commissioned officer would then place a pile of silver dollars on the drumhead and begin talking to the crowd. If a person wished tc join he advanced to the drum, took one of the dollars, and became part of the regiment. When a sufficient number of recruits had been obtained, the squads departed for their encampment.

At the time of the Creek War, Colonel Williams had between 550 and 600 men under his command. He encountered many problems in trying to feed and clothe his little army. Little luck was had in securing arms for the regiment. These were the model 1808 Harpers Ferry smoothbore flintlock .69 caliber. Thus one year after being raised, the regiment was still drilling and drilling and drilling. The men longed for some action. However, there were many conflicting needs and uses for the 39th regiment in 1813.

Governor Blout of Tennessee wanted to use the regulars to support General Andrew Jackson's Tennessee Militia in the Creek War. The defense of New Orleans and the Mississippi was also a major concern. There was great confusion concerning the military authority in the Southwest area at this time. Still the regiment drilled.

At Fort Hampton, the parade ground at Knoxville and elsewhere, drill and more drill. Because of this confusion, the 39th was a victim of conflicting orders from the outset. The infant 39th was ordered to help Jackson AND defend New Orleans at the same time. Williams had to sort out all the conflicts during the fall of 1313. In December he was ordered by General Thomas Pinckney to join Jackson and remain with him unless ordered by the War Department to serve elsewhere.

In January, Williams was again ordered to New Orleans, but General Pinckney told him to remain with Jackson. Finally Judge Hugh Lawson White was able to use his considerable influence to have the regiment re-assigned from its marching orders to New Orleans to Jackson's Army. It should be pointed out that the only other regular regiments in the entire 7th Military District were the Second Third, Seventh and Forty-Fourth, with a total effective strength of 238 officers and men. The Seventh and Forty-Fourth were composed mostly of Creoles from Louisiana.

Uniform

Before proceeding furthers a brief description of the 39th's uniform is in order. The basic uniform consisted of light grey/blue trousers, white vest and shirt, dark blue wool coatee, white belting black shako with white cording, and either brown or black common shoes with one eyelet. Black gaiters were also part of the kit. For summer issue, linen pantaloons and coat were issued.

B<>March

On January 12th, 1814, the regiment started its march down into the Mississippi territory, marching down from Knoxville to Fort Deposit at Thompsons Creek on the southern most point. of the Tennessee River.

Upon reaching Fort Deposit, Williams found that no military stores had arrived and the existing supplies and provisions were depleted. From Huntsville, Williams informed Jackson that only one hundred eighty of his six hundred men were armed. While the regiment as a whole were good shots, being recruited from the frontier, the men were very slow to totally grasp the fundamentals of battle tactics.

At this time Williams requisitioned four strong horses to haul a few pieces of artillery. This suggests regimental guns made up of specially trained infantrymen.

Jackson's plan for the 39th was to "sweep the Coosa and Cahaba, cross the Coosa to its Eastern Banks scourge and scour the Hickory Ground, form a junction with the Georgions and with aid of supplies, destroy in fifteen days every warrior on the Tallapoosee." Jackson was also relying on the regular troops to help form some discipline, order and subordination within the ranks of his increasingly hostile Tennessee Militia.

The 39th moved down the Coosa River to Ten Islands and Fort Strother, (arriving on February 6th), in order to support Jackson, but arrived to find that Jackson had meanwhile been defeated at Emuckfau Creek. So here they rested, drilled and prepared for the coming action.

At this time is was learned that the regiment was without music. Troop movements of the day were conducted by drum roll and rhythms, Edward Hunt who was an enlisted drummer which he denied, was apprehended as a deserter in Knoxville during the summer of 1313, and placed in the ranks of Captain McCelland's unit of the 7th Infantry. Williams found out about Hunt and ordered him to the 39th to remain until further ordered. After some friction between the 7th and the 39th, Punt remained with the 39th. It was found that Hint was not enlisted, but he remained to instruct some raw music to the 39th. Jackson and his commanders were certain an army could not be disciplined without music. While it has not yet been documented, like most other regiments, the musicians of the 39th probably wore reversed colors, or even a red coatee.

Following an inspection of the regiment, Jackson's final advance from Fort Strother began on March 14th, 1814. Here he left four hundred fifty men to garrison the fort and bring up supplies and push them forward. At Cedar Creek on the) Coosa, Jackson constructed a fort which was named after Colonel Williams, from which to operate against the Red Sticks at Tohopeaka.

Discipline was strictly maintained during the long march. Fort backtalking an officer, one man was executed by firing squad. It was a strong example, but one that left an impression on the rank and file.

Jackson and his army marched overland from Fort Strother to Fort Williams. Jackson had assigned the quartermasters stores and military provisions to Williams and the 39th. Williams and his men constructed flat boats and loaded them with the supplies, then floated them down the Coosa to Fort Williams. The trip was made with great difficulty for in some places the river was almost impassable. Having left on the 18th of March the little fleet reached the' fort on the evening of the 21st.

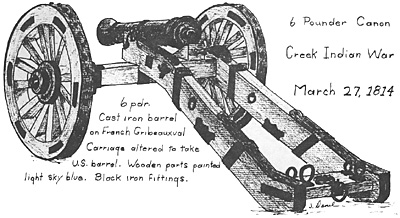

After a short period of rest (no drills), Jackson was ready to move upon the Red Sticks, the name given to the hostile Creek Indians facing him. He therefore put his army in motion on the 24th cutting a military road east across the fifty-two and a half miles which separated the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers. Williams and the 39th were still struggling with the military stores, cannons (one six pounder and one three pounder plus wagons).

Day after day the small army marched through the wilderness with their attached Cherokee Scouts, who wore a deer tail in their hair for easy identification in combat. Camp was made about six miles to the north and west of the Horseshoe on the evening of the 26th. It was then that Major Montgomery conducted an unofficial tour of the bivouac, talking with every officer, non commissioned officers and ensigns. Durirn the night's conversations concerning the pending actions took place between all ranks, as, unlike most Napoleonic armies the U.S. enlisted man had the right to address their officers informally around the evening;s campfires.

At dawn, near 6:30 A.M. on March 27th, 1814, General Jackson began his march to the Tohopeaka and prepared to attack the hostiles. Moving his army into position, he sent General John Coffee and his mounted riflemen and Indians to cross the river and surround the bend. He massed his supply and ambulance wagons around the base of Cotton Patch Hill and placed his two cannon on Gun Hill overlooking the Indian barricade.

Jackson observed that an army could not approach the five to eight foot high barricade without being exposed to a double and cross fire from the two rows of port holes.

Jackson observed that an army could not approach the five to eight foot high barricade without being exposed to a double and cross fire from the two rows of port holes.

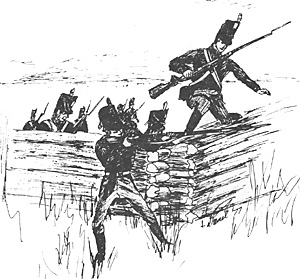

The 39th was massed on the left of the battle line facing the barricade behind the advance guard. The Tennessee Militia, dressed much like the Militia from Kentucky, were on the right, with Gun Hill to the right. and rear of them. When the drum roll sounded, the 39th moved forward and was thrown into the thick of the fighting, supported by the East Tennessee Brigade. Colonel Williams and Major Montgomery led the charge, advancing steadily in the face of arrows and bullets. Hand to hand combat ensued across the barricade.

Then Major Montgomery leapt upon the fortifications urging his men to follow. As they did, the brave major, whom Jackson was later to call the 'Flower of the Ammy', spun and dropped, a musket ball through his forehead. Wild fighting ensued and the contest was the fiercest around the area of the 39th. However, with expert use of the bayonet, the regiment was soon able to route the Creek warriors from their positions.

Besides Montgomery, Lieutenants Moulton and Somerville were killed in the fight. The 39th lost seventeen men killed and fifty-five were wounded, three of whom later died. One of the wounded was a young Ensign, Sam Houston. He had been assigned to the 39th as a flag bearer, but could not be content with staying out of the fight. While storming the barricade he received a deep wound in the upper left thigh with a barbed arrow.

Later in the day, after being somewhat patched up, he was again wounded, receiving a musket ball in his right. shoulder and a second in the right hand. He was borne from the field helpless. While not serious by today's standards, the wounds almost took Houston's life and changed the course of Texas and American history, especially as the doctors had given up and neglected to even cover the young Ensign or administer water.

The 39th Infantry played a major role in the fighting at Horseshoe Bend and Jackson was quick to praise them for their job. After the battle, Colonel Williams was faced with a serious problem. He wrote to Secretary of War John Armstrong on April 4th stating that "one half of the officers and about one sixth of the troops of the 39th engaged in the battle of Tohopeaka on the 27th Utl, are amoung the killed and wounded. Also hardship and disease on the country's frontier had a hard effect on the troops.

Following the action, the army rested on the field of combat, spending the evening of the 27th re-organizing, burying the dead and caring for the wounded. The next day, the army retired upon Fort Williams with the wounded being carried on stretchers slung between two horses. At 3:00 P.M. on the 31st, Fort Williams was reached.

Colonel Williams was shortly sent back to Tennessee to recruit the regiment's losses, making Lieutenant Colonel Benton the acting C.O.

When the Creek War ended in August of 1814, the 39th was again ordered to New Orleans by General Pickney. However the regiment remained at Fort Jackson (Fort Toulouse) area until August; thin after the repulse of the first British attack on Fort Bowyer, the regiment, along with the Second and Third Infantry was kept in the Mobile area.

Congress, on March 3rd, 1315, set up an act for a peace time army of 10,000 men to be divided among infantry, rifle and artillery regiments. All cavalry was to be eliminated and the number of regiments of infantry reduced from 46 to 3. Rifle regiments were consolidated into one unit.

The 39th was consolidated into the 7th Infantry along with the remnant of the 8th and 24th regiments. Some of the officers were transferred to other units. For example Houston was transferred early in 1815 to the First Infantry at New Orleans and promoted to Second Lieutenant. The last of the 39th was turned over to the new 7th Infantry on May 17th, 1815, and this unit of infantry which had served the United States for a little over two years, passed out of service.

DOCUMENTATION

Bishop, Curtis, Lone Star Leader, Sam Houston, Julian Messner, New York, 1968.

Lathams, Jean Lee, Retreat to Glory: The Story of Sam Houston, Harper and Row Publishers, New York, 1965.

Johnson, William, Sam Houston, The Tallest Texan Landmark Books, Random House, New York, 1953.

Letters dated April 13th, 1976, Superintendent James F. Kretschmann May 10th, 1976, Seasonal Park Technician Mark Spier August 7th, 1977, Park Historian Paul A. Ghioto

Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Route 1, Box 63 Daviston, Alabama, 36256

Battle Flag September, 1973, Pages 20-26.

Miscellaneous Notes

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 21

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1978 by Jean Lochet

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com