We are in the process of reevaluating our firing rules for

muskets and rifles. It is again a difficult subject since quite a

bite of the available data is colored by some interpretations often

far away from realism. However, I think we can play safe by using as

starting point, the experiment made by the Prussian Army toward the

close of the eighteenth-century and related in David Chandler THE

CAMPAIGNS OF NAPOLEON page 342:

We are in the process of reevaluating our firing rules for

muskets and rifles. It is again a difficult subject since quite a

bite of the available data is colored by some interpretations often

far away from realism. However, I think we can play safe by using as

starting point, the experiment made by the Prussian Army toward the

close of the eighteenth-century and related in David Chandler THE

CAMPAIGNS OF NAPOLEON page 342:

- "... the Prussian army conducted some field firing experiments

with their own muskets which differed little from its French

counterpart in terms of accuracy. After setting up a canvas target

100 feet long by 6 feet high to simulate an enemy unit, they drew

up a battalion of line infantry at varying ranges and ordered the

men to fire a volley. At 225 yards distance, only 25 per cent of

the shots fired hit the target; at 150 yards the proportion was

40 per cent; at 75 yards, 60 per cent of the shots told. It would

appears therefore that the number of casualties caused by deliber-

ately aimed rounds fired at normal range were comparatively slight;

most troops were killed or wounded by artillery fire or "casual"

bullets.

However, when fire was held until the troops could literally see "the whites of the enemy's eyes -- say 50 yards -- horrific casualties could result, often as many as 50 per cent of a unit's personnel -- or even more. Thus, at Austerlitz the 36th Regiment lost 220 out of 230 of its grenadiers, while at Auerstadt (1806) Gudin's division lost not less than 124 officers and 3500 men killed and wounded out of a total of 50OU men committed to action."

The above quotation is in full agreement with FIREPOWER. To be objective one should not conclude that at 225 yards 25 per cent of the front rank was killed or wounded. Obviously some of the shots hit twice the same men and some also failed to hit anyone because of the spacing between soldiers. The above experiment was also conducted under ideal conditions far away from the conditions of a battlefield obscured by smoke, obstacles etc. and by very steady soldiers unaffected emotionally by the battle conditions like the - very fact of being fired on by. the enemy. No doubt that the effectiveness of a volley was much less in the field. However the possibility existed. In our present musket fire rules the volley range is limited to 18 inches i.e. 180 yards; that appears to be a happy compromise.

An important point to take in consideration is that the above data is dealing with volley fire and not aimed fire. to fire at a man size target is a different story than firing at a target 100 feet long by 6 feet high. The ordinary line units in general were not trained at aimed fire with perhaps the exception of the elite companies or the light troops.

Perhaps we should remind here that French skirmishers were trained to operate in pairs and capable of aimed fire called "feu de chasseur". Apparently that was done as early as 1754 and recommended by the Ordonance of 1754. Reference Quimby THE BACKGROUND OF NAPOLEONIC WARFARE page 85.

Even with a Baker rifle striking a man size target was not an easy task. THE UNIVERSAL SOLDIER page 118 tells us that at 300 yards a very good shot could hit the figure of a man 6 times out of 10. It was certainly less for the average riflemen. Needless to say that such fire was also greatly affected by battle conditions, and the results of fire could be much less than under ideal target practice conditions. Fire against skirmishers and artillerists was very ineffective and several examples of that can be find in many books like the CAMPAIGNS OF NAPOLEON page 87, etc.

Fred Vietmeyer in an article in the Courier (Vol. V/ No. 6: pages 24 and 25) gives several interesting references on muskets and rifles. Rifle fire is given an effective range of "certainly" 150 yards and considerably more for some marksmen, while the musket's effective range is shown to be 75 yards, though Richard Glover reports best results for the musket up to 160 yards in PENINSULAR PREPARATION, page 114. Jack Weller reports better than 50% accuracy for a rifle at 150 yards, and Richard Glover gives almost 1/6 chance of a rifle hit at 300 yards.

Why so much on ranges? The proposed rule change on musket and rifle fire in NJN # 18 limits the musket range to 12 inches i.e. 120 yards. I personally feel that the actual 180 yards is not unrealistic. However, I am the first one to agree with Dick that the short range effect is too low and the long range effect too high. Also the skirmisher fire is to effective against other skirmishers and nonformed troops such as artillerists etc. Dick's effort is appreciated and necessary but needs only few changes. Oman in WELLINGTON'S ARMY pgge 301 says on the Brown and Bess musket:

- Its effective range was about 300 yards, but no accurate shooting, could be relied upon at any range over 100. Indeed, the man who could hit an individual at that distance must not only have been a good shot, but have possessed a firelock of over average quality. Compared with the rifle, already a weapon of precision, it was but a haphazard sort of arm. At any distance over the 100 yards the firing-line relied upon the general effect of the volley that it gave, rather than on the shooting of each man.

I think the key point is: At any distance above 100 yards the firing line relied upon the general effect of the volley that it gave, and also ... its effective range was about 300 yards, but no accurate shooting could be relied on at any range above 100. That is in full agreement with the Prussian experiment related above. The explanation appears to be in the difference of volley fire versus individual fire. It's the only logical explanation for all the different ranges given by the different sources and apparently in contradiction. My explanation is that musket fire in volley was effective up to close to 200 yards against a formed troop of a battalion size and that casualties could be inflicted up to that range. It appears however that the precision of fire dropped sharply above a certain range which appears to be in the order of some 75 yards, for the simple reasons that the soldiers of most armies were not trained to aim their weapons with great accuracy with perhaps the exception of the British infantry and elite troops of other nations.

Even firing at close range presented some problems. It is astonishing to read some battle accounts and find that on occasion some entire battalions fired at almost point blank and failed to inflict severe casualties. In AUSTERLITZ page 253 Claude Manceron reports that the Russian infantry opposed to Lannes 5th Corps formed a compact mass, however the musket volleys were much less precise than the French fire because the young Russian soldiers were so poorly trained that they fired above the French.

The French Marshal de Saxe in the beginning of the 18th century had very little respect for musket fire. It is difficult to understand how de Saxe came to this point of view. He cited numerous examples of the effectiveness of fire, the best of which was one experimented at the battle of Belgrade in 1717, in which two Austrian battalions fired a volley against attacking Turks at 30 paces. The volley and melee were practically simultaneous, and the two battalions were cut to pieces with only four or five men escaping. Among these was de Saxe himself. He was later over the ground and counted only thirty-two Turkish dead from the point blank volley. Saxe may have changed his mind fifteen years later after seeing his whole front rank laid low by the British with a single discharge at Fontenoy.

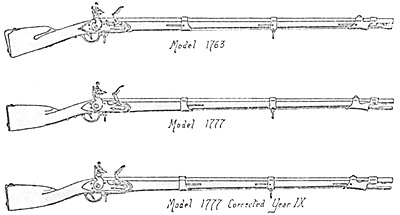

Perhaps it would be of interest to publish here the characteristics of the French Charleville musket since also here a great deal of conflicting and confusing reports have written on that weapon. The French Charleville was used by the French infantry until about 1823. It was used also during the war of the American Independence both by the French and the American forces. The U.S. Army was in 1812-1814 using a modification of the Charleville. THE AMERICAN WAR 1812-1814 edited by Osprey (MAN at ARMS series) says pages 23 and 24, the basic infantry weapon was a .75 calibre smoothbore India Pattern "Brown and Bess" flintlock musket.

While the "Bess" served long and well, it was inferior in several ways to the American musket. It had a larger bore than the American weapon, meaning the American model was considerably lighter. Then, on page 31, "...The American musket, made in Springfield, Harper's Ferry or by contractors, was a copy of the 1777 French musket, with all iron furniture and a .69 calibre ball ....."

The French magazine GAZETTE DES UNIFORMES, # 26 July-August 1975 page 30 says:

- "Infantry musket model 1777(system Gribeauval weapon of the

(French) infantryman until about 1823 and received only small

modifications in the Year IX... the precision was great up to 150

meters, poor from 150 to 250 meters and almost nil behind that

distance, however the projectile was dangerous up to 800 meters.

The French light infantry was equipped with a slightly different

version of the Charleville. It is of interest to note that the

Charleville had a raised sight but apparently no V-block backsights

like the New Land Pattern Light Infantry Musket provided from 1810

to the 43d and 52nd and the Portuguese Cacadores. The barrels of

the new British light infantry muskets were also more carefully

bored and finished, so that with careful loading some increased

accuracy was achieved. Ref. THE UNIVERSAL SOLDIER page 126.

It appears that the muskets of the other Nations were more or less comparable with perhaps, according to Christopher Duffy BORODINO page 42, the worst being the Russian muskets. In 1812, the Russians went to war with twenty-eight different calibres of infantry muskets.

I think at this point we should begin to draw some conclusions. Otherwise, we can go on for ever giving apparently contradictory references. The first point that must be taken in consideration is the theoretical performances of t musket. That is mot easy to find. In my opinion, the best book reference book Published to date is FIREPOWER. It is very complete. Furthermore, several battle analysis, add to the pertinence of the remarkable work performed by the author, Major-General B.P. Hughes. In addition the data published checks very closely with other reliable data and use very carefully the work of many reliable sources, many from actual battle reports and tests.

A key point is published in FIREPOWER, page 27, on the accuracy of the French musket fired at 150 meters (about 160 yards). The error of the Charlesville at that range is given as:

- (1) in height 75 cms or 30 inches

(2) laterally 60 cms or 22 inches

That means the musket ball of such a musket could hit a rectangle

of 1.5 meter (or yard) by 1.2 meter (or yard) at 160 yards. If one

considers the size of a man being about 20 inches by about 68 inches,

we come with a little better than a 20% chance to hit such target at

150 yards. That is of course if the target does not move. If the

target is laying down, the probability to hit it is cut down

drastically simply because the target is of much smaller size.

That means the musket ball of such a musket could hit a rectangle

of 1.5 meter (or yard) by 1.2 meter (or yard) at 160 yards. If one

considers the size of a man being about 20 inches by about 68 inches,

we come with a little better than a 20% chance to hit such target at

150 yards. That is of course if the target does not move. If the

target is laying down, the probability to hit it is cut down

drastically simply because the target is of much smaller size.

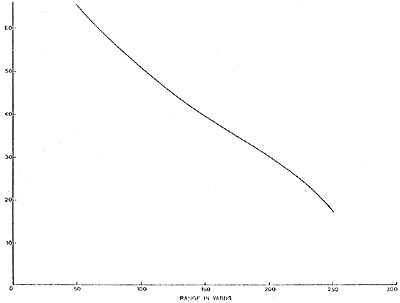

It becomes obvious that the more compact the target the easier it becomes to hit it. Thus it is easier to hit a compact target such as a square that a more "diluted" target like a line or skirmishers etc. I also think that a pertinent piece of information is the diagram published in FIREPOWER, page 30, on the theoretical performances of the musket (mean of records from Picard, Muller and Greener) as the theoretical percentage of the shots hitting an infantry line.

The same reference, page 164, claims that in a battle the musket could develop its maximum effect perhaps between 30 and 100 yards and from 100 to 200 yards it was only capable of rapidly diminishing effect. Page 167 the effect at long range is given: ... "It is probable that some of 50% of the bullet fired at 200 yards could have reached their target; but when allowance has been made for the difference between a human mass and a practice target, it would be reasonable to assume that about half of those bullets would have taken effect.

It is also very important to take in consideration that above about 100 yards the vertical drop of the musket ball become significant. Consequently, only troops that have been trained to compensate for such a vertical drop will be capable of having an efficient fire above 100 yards. That may appear obvious to our 20th century minds, but was not the common recruit of the Napoleonic era! Do not take my word for it. Just open the book BORODINO by Christopher Duffy, page 41. Apparently only in 1811, such a practice was introduced in the Russian Army by the Instructions for Target Practice! Such Instructions described how a target two yards high and just over two feet wide should be painted with horizontal stripes so to accustom the men to elevating or depressing the musket barrel according to the range. As previously reported in this article the effect of such lack of training could be catastrophic (see the quotation from Austerlitz).

The theoretical performances of the musket was, of course, greatly affected by the battle conditions, often called the "inefficiency of the battle field". Here again, I very strongly recommend the reading of FIREPOWER. The analysis of several battles give a very good understanding of what happened in a battlefield.

Another point often ignored is that "apparently 15 to 25% of the shots fired apparently misfired..." ref. FIREPOWER page 165). It is grounds enough to justify a bonus for the first volley fired by a battalion etc.

The other points affecting the efficiency of musket fire can be:

- training

animation and size of the target

type of target

visibility of the target (smoke)

human error

position of the firer

morale or stress of the firer.

I think we have in the above article covered most of the pertinent points that must be taken in consideration to make realistic rules for musket fire. The discrepancy in the musket range is more apparent than real. I think in spite of the apparent contradictions all the authors meant about the same. Again we say that the magic figure of 100 yards was the turning point, and I will conclude with a last quotation from FIREPOWER page 26:

- "The musket of the 18th century, with its heavy spherical bullet,

its large windage and its low muzzle velocity, had a poor ballistic-

performance. Greener states that a bullet dropped five feet vertically

over a distance of 12O yards from the muzzle. As a result, it was

possible for a good marksman to hit a man at 100 yards: a volley could

be fired with some chance of obtaining hits on a mass of troops at 200

yards; but at 300 yards fire was completely ineffective."

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 20

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1977 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com