The operations of the Royal Guard in Tuscany had been far from glorious. For various

political reasons, King Joachim I, ( Murat) had made a detached command of the Royal Guard

and had moved it to the Po Valley between Rome and Florence. Numbering almost seven

thousand officers and men, under Generals Pignatelli-Strongoli and Livron, the Guard had

maintained a fair march discipline inspite of the large desertion rate. Most of those who did

desert were men of northern Italian origin and veterans of the Spanish and Germanic wars.

The operations of the Royal Guard in Tuscany had been far from glorious. For various

political reasons, King Joachim I, ( Murat) had made a detached command of the Royal Guard

and had moved it to the Po Valley between Rome and Florence. Numbering almost seven

thousand officers and men, under Generals Pignatelli-Strongoli and Livron, the Guard had

maintained a fair march discipline inspite of the large desertion rate. Most of those who did

desert were men of northern Italian origin and veterans of the Spanish and Germanic wars.

Arriving in Florence on the 8th of April, fully five days behind Murat's timetable, they remained there, inactive, for a further seventy-two hours, thus jeopardizing the entire campaign.

On April 11th, the command marched out of Florence towards Pistoja. Unfortunately for the Neapolitans, both of the Guard generals harbored a fear of their Austrian counterpart General Nugent. This blinded and revented them from realizing that the Austrians possessed only a small detachment of regulars plus some Tuscan levies. Half-heartedly then, the Neapolitans searched for but couldn't locate their enemy. When reports were received that Austrian cavalry was hovering on their flanks the Neapolitan generals resolved to withdraw. Their decision may also have been prompted by Murat's orders enjoining caution, to keep the Guard intact and to begin a slow withdraw via Arezzo and St. Sepokro.

Naturally this made the Guard generals very happy and for once they moved quickly and efficiently reaching Cortona on the 16th, which was more than fifty miles south of Florence.

Meanwhile Murat's positions covering Bologna were forced by the Austrians General Bianchi, which was then abandoned on the night of the 15th.

Murat's forces totaled 45,000 effectives. However, the Austrians, thinking that the Neapolitans were demoralized, split their forces into two equal wings with a range of mountains between them.

While the regular Neapolitan line was greatly disorganized, Austrian General Frimont greatly underrated the fighting quality of the Royal Guard as well as the considerable personal factor represented by King Joachim. (The reader should bear in mind that other than a token Palace Guard, Austria possessed no Guard Troops). [Johnston, R.M Napoleonic Empire in Southern Italy MacMillan and Co. Limited, New York, New York, 1904, volume 1, Pg. 360.]

Thus in the closing days of the month, near the fortress of Ancona, the Guard joined the main army. Here on April 30th, Murat came face to face with the cautious Pignatelli-Strongoli, whereupon a violent scene of recrimination took place. Perhaps Murat should have relieved him of command but he didn't. This fateful decision would not only cost Murat the forthcoming battle, but his kingdom and eventually, his life.

At this point the Guard numbered some 5,400 infantry, 1,900 cavalry, and sixteen guns while the main army fielded four line divisions (Lecchi, Carascosca D'Ambrosio and Rossetti) numbering some 35,000, plus 5,000 cavalry, and sixty artillery pieces. Counting gunners, sappers, staff and escorts the Neapolitan Amy thus numbered almost 50,000, far below the authorized paper strength of 95,000. Millet de Villeneuve was Chief-of-Staff, with Pedrinelli, chief of artillery and Colletta Chief of engineers. Murat was thus short of light infantry and heavy cavalry, while the officers of artillery were ill-trained. [2. Ibid. page 354.]

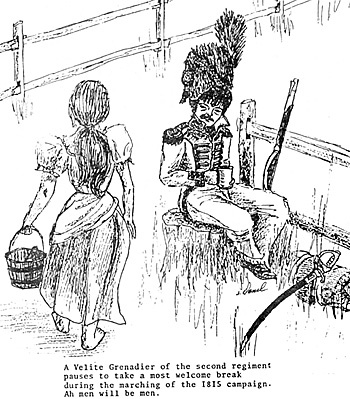

The organization of the Guard Infantry was very much like its French counterpart, which included the Battalion du Marin de la Garde, the 1st and 2nd Velite Grenadier Regiments and the Guard Grenadiers. The Guard cavalry was bigger in theory per squadron than the French, but fielded much less.

The Battle of Tolentino

With the Austrians still moving south, Murat suddenly realized that he enemy lay in two wings, each incapable of swiftly supporting the other. He therefore resolved to attack, defeating each Ung in turn. Because of its proximity to his immediate lines of communications Murat chose to strike the wing of General Bianchi first. He therefore concentrated his remaining divisions near the city of Macerata.

On May the Second, advanced elements of the Neapolitan line were sent to attempted a reconnaissance in force towards Tolentino which had been occupied by the Austrians the day before.

On the Third, Murat advanced his lines up the valley of the Chieti, with the Royal Guard following on the Fourth. It had been Murat's intention to attack Cassone with the Guard and when that operation had drawn sufficient Austrian forces into the battle, the main army would move forward from its central position at Monte Milone with General Lecchi's Division swinging around behind the AustriaAls left flank.

Had Murat's orders to his subordinate commanders been carried out to the letter, he would have thus had some fifteen thousand troops deployed for battle. However, the best laid plans of men...and they did go astray due primarily to the failure of the commissariat department in not having sufficient and proper rations available, the troops were forced to scatter in search of food. Equally disastrous to the Neapolitan cause were the hurt feelings and vanquished pride of the Commander of the Guard from his recent, rebuke by Murat.

The Royal Guard was only able to obtain the scantiest of rations and this by the plundering of the houses of Macerata.

Around nine in the morning, the Guard was deploying between Monte Milone and the Chieti. However the division comprising the army's right flank was not yet under arms while the reserves I under General Lecchi, were still so dispersed in their search for food, that not even a single battalion could be collected.

Under these circumstance it defies any rational thought that a commander would provoke action, yet the commander of the infantry of the Guard, either through indiscipline, folly, or selfish pride, threw away any chance of success, by advancing the Guard as soon as they were deployed, thus joining the battle.

Murat upon arriving at the sound of the firing, found that he could not disengage his Guard and therefore decided to direct the fighting as well as the circumstances would allow. The infantry advanced and after some very heavy firing was able to carry Cassone by the bayonet. However, the ground immediately beyond was covered by Austrian artillery, which prevented any further penetration by the Guard. The Guard had acted as duty had demanded. But clearly, they couldn't face the entire Austrian force alone and when the Neapolitan left flank broke, there was nothing to do but withdraw, later developing into a full retreat. And retreat for the Neapolitans was disastrous.

Though the battle had been won by them, Austrian General Bianchi would later declare in his report that the Neapolitan Royal Guard had shown great courage.

Losses for the battle were 720 killed or wounded with 2,000 taken prisoner for the Neapolitans against a loss total of 800 for the Austrians.

When the retreat began, the Neapolitan generals abandoned their troops and rode to Macetra. Here an informal meeting at Murat's headquarters evolved into a name-calling and insulting occasion that produced little but additional hurt feelings and mutual distrust.

The following day May 3rd, the retreat south continued and proved more disastrous than the battle itself. Between the Chieti and the Tronta rivers Murat lost three-fourth's of his remaining forces. Many of the soldiers of the Guard deserted, while the Neapolitan line mutinied or just went home. What remained of the army arrived before the gates of Naples on May 12th.

Meanwhile Murat had somehow gathered five thousand troops on the Liri for a final stand. Unfortunately when another Neapolitan division of four thousand were surprised by the Austrians and totally dispersed, military operations ended for good.

Gone was the Kingdom: Gone was the Guard; Murat's future was indeed bleak.

DOCUMENTATION

1. "Naploenic Empire in Southern Italy" R.M. Johnston, MacMillan and Company Limited, New York 1904 Volume 1. -

2. "Uniforms of the Napoleonic Wars 1796-1814" by Jack Cassin- Scott Hippocrene Books Inc. New York, 1973.

3. "Napoleonic Organization" by Ray Johnson, The Wargamers Library, Volume II, Daum Printing Company, Dayton Ohio.

4. "Arms and Uniforms, The Napoleonic Wars", by Liliane and Fred Funcken, Ward Lock Limited, London, 1973, Volume II.

5. Tradition, # 68 Pages 1, 19.

6. Napoleon's Satellite Kingdoms

7 Correspondance from Ray Johnson and Fred H. Vietmeyer.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 18

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1977 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com