The "Six Days" Campaign was followed by another brilliant maneuver, that, if executed as ordered, would have raised havoc with the Army of Bohemia. It took all the skill of the careful Schwarzenberg to avoid disaster. Nevertheless, the French maneuver affected Allied morale at least temporarily and forced the Allies back beyond Troyes.

The "Six Days" Campaign was followed by another brilliant maneuver, that, if executed as ordered, would have raised havoc with the Army of Bohemia. It took all the skill of the careful Schwarzenberg to avoid disaster. Nevertheless, the French maneuver affected Allied morale at least temporarily and forced the Allies back beyond Troyes.

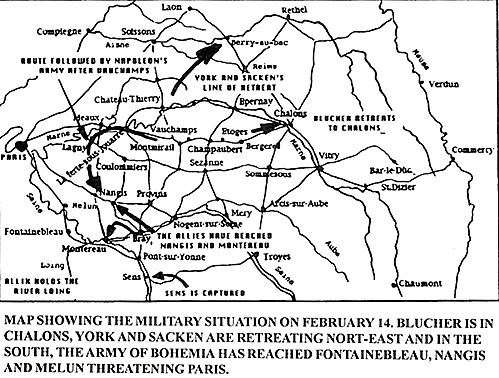

MAP SHOWING THE SITUATION ON FEBRUARY 14, BLUCHER IS IN CHALONS, YORCK AND SACKEN HAVE RETREATED IN THE NORTH AND IN THE SOUTH, THE ARMY OF BOHEMIA HAS REACHED FONTAINEBLEAU, NANGIS, AND MELUN THREATENING PARIS.

After he had decisively defeated Blucher's command and pursuing him as far as Chalons if

necessary, Napoleon originally planned to fall upon Schwarzenberg's communications.

[1]

However, it became obvious that his marshals in the south would be unable to hold Schwarzenberg for the two or three days necessary to perform that maneuver.

[2]

During the battle of Vauchamps, Napoleon had already made up his mind to move back south to deal with Schwarzenberg's Army of Bohemia. Schwarzenberg's advance guards had reached Fontainebleau, dislodged Allix from the line of the river Yonne, taken Montereau and Melun and had reached as far as Nangis. Paris panicked once more. [3]

To bring his army south, Napoleon had to choose between two routes. The shortest one was by the road from Champaubert to Sezanne, where the army bivouacked. However, it had been completely broken up by the combination of a week of heavy ram and the passage of his army a few days earlier. The second choice was the transverse road from Meaux to Melun which passed through Guignes. It was surfaced and in excellent condition. Consequently, Napoleon decided to take the longer road via Meaux and Sampuis. [4]

The couriers from the south did not bring good news. The Army of Bohemia was making considerable headway toward Paris. Up to February 13, the Emperor was not altogether concerned as long as the bridge at Nogent was kept in French hands. [5]

He wrote to Joseph from Montmirail on February 13 after he had received news about the Allied advances [6] :

Thus, as long as Nogent could be held, the Emperor felt confident that the Allies would not move against Paris in strength from the south or the valley of the Seine. Disturbing news soon changed the picture. On the 12th, an Allied column surprised the weak National Guard garrison at

Bray-sur-Seine [7] and captured the bridge there. The same thing happened at Pont-sur-Seme, near Montereau. The enemy had now captured two bridges to the west of Nogent and Victor was menaced with being cut off. The Marshal had no choice but to withdraw precipitately and abandon the bridge at Nogent intact. Oudinot was not strong enough to contain the Allied onslaught and he too had to withdraw. The situation was now critical and the road to Paris by the left bank of the Seine was wide open. The Allies had reached Provis, Nangis, Montereau and Fontainebleau.

What Napoleon did not know was that Schwarzenberg had ordered his army to halt and await the

development of the military situation. The defeat of Blucher and the setback suffered by the army of Silesia had raised considerable concern at the Allied High Command. The Allies became very careful and hesitant. Their advance ground to a halt. [8]

Consequently, from February 15-17, the Allied troops under Schwarzenberg's direct command

maintained their positions and awaited Napoleon's maneuvers. [9]

In Napoleon's mind, Schwarzenberg had committed the same error that Blucher had made. His

command was scattered over 20 miles and he saw the opportunity to fall on the flank of the Army of Bohemia and defeat it in detail. From Champaubert, on the eve of 14th, the Emperor dispatched a multitude of new orders to coordinate a large concentration of troops around Guignes, where he would show up with the bulk of his troops. Macdonald was sent to Brie-Comte-Robert; Marmont and Mortier were to defend the lines of rivers Marne and Aisne; Victor, Oudinot and Macdonald had to hold the line of the river Yerres at all costs.

The Concentration around Guignes and Chaulnes

Then, without taking any rest, Napoleon went to Montmirail followed by Ney, the Guard, and

Grouchy's cavalry and from there to Meaux. He was to accomplish one of the most outstanding forced marches of his career. Transporting his infantry 'in requisitioned wagons and carts on the excellent metalled road from Meaux to Melun, he covered 47 miles in less than 36 hours."

[10]

He arrived at Meaux on the 15th and moved south via Couilly-Pont-aux-Dames and Fontenay. On

the 16th, he reached Guignes, where the Guard rendezvoused with Victor, Oudinot and Macdonald.

The Emperor had arrived at sunset, just in time to repulse the Russian skirmishers which had been pressing Victor and were taking position between the Guignes and Chaulnes. It was precisely where Napoleon had announced he would appear. Everything had been so well orchestrated that, at that very moment, Valmy and his Corps and Treilhard and his Division arrived from Spain. On the same day, after moving in accordance with similar orders, other troops recalled from Pan's and elsewhere also arrived at the appointed rendezvous. Around the village of Guignes, Napoleon had concentrated over 50,000 men. [11]

De Segur to say:

"At that moment... Everyone understood that he was about to fall on that first enemy's

vanguard, overwhelming it and pushing it back by Nangis, Nogent, Bray and Montereau, from

where he would take in the rear the enemy's surprised Corps dispersed on both banks of the Seine... in the same fashion he just had defeated that of the army of Silesia between the Petit-Morin and the Marne. [12]

The Destruction of Pahlen's Command

On the evening of the 16th, the orders to attack the next day were issued from Imperial

Headquarters. The troops moved to their assigned positions. The news about the success of the previous battles at Champaubert, Montmirail, Chateau-Thierry and Vaucharaps had boosted morale. There was hope again that the enemy could be defeated. [13]

Schwarzenberg had probably anticipated Napoleon's flank move. On the 17th, Generals Wrede and Wittgenstein were ordered to slowly withdraw through Bray while Barclay and the reserves concentrated at Nogent. However, these orders arrived too late as Napoleon was closer than he had anticipated.

Wittgenstein had not followed Schwarzenberg's order. He had reached Provins when he had

received the order to halt. He spurned the order and continued to advance to Nangis sending forward his advance guard under Count Pahlen to Mormant.

On the eve of the 16th, the unfortunate Pahlen learned that he was facing the entire French army under Napoleon. He immediately notified his commander but received no answer. On reading the report from the general commanding his advance guard, Wittgenstein thought Pahlen exaggerated the danger. [14]

Pahlen was in a very critical situation. With his 12 guns, 8 battalions (4,000) and 24 weak squadrons (2,000), he was in no position to resist an entire army. As at Champaubert, the carelessness of an Allied general had uselessly compromised a large command for the second time in two weeks.

On the morning of February 16, Victor ordered Gerard's infantry and Grouchy's cavalry to

immediately attack Pahlen. The unfortunate Pahlen deployed his troops, covered them with a cloud of skirmishers, formed his infantry in square and began to retreat. His cavalry was too weak to oppose

Grouchy's cavalry.

Meanwhile, Schwarzenberg notified Wittgenstein of his disapproval of the latter's advance on

Nangis and Mormant. The Austrian general added that when he had ordered Wittgenstein's and Wrede's Corps to the right bank of the Seine, it was not with the intention of an advance on Paris. [15]

Receiving this disapproval, Wittgenstein retreated to Nangis but Pahlen was under attack and could not disengage as easily as his commander. He was soon overwhelmed by the French attack. At first, Pahlen was able to withdraw in good order, but Napoleon, near Grand-Puits, called up Drouot with the 36 guns of the Guard.

The result was obvious. The powerful artillery concentration pulverized the Russians. Vainly, Pahlen asked for help from Hardegg, commanding Wrede's Austrian/Bavarian advance guard nearby. He was abandoned by all. All his battalions were annihilated and the survivors surrendered. A desperate Pahlen was pushed back with the remains of his cavalry on Hardegg in Nangis and escaped only by abandoning his 12

guns and 50 caissons in the process. The remainder of his command disintegrated in several directions. It was Champaubert repeated! But would it be another Montmirail and Vauchamps?

Victor's Drive for Montereau

Two hours later, Victor drove Wrede's vanguard out of Nangis in disarray and shortly after had a sharp encounter with Wrede at Valjouan some 3 miles south of Nangis and pushed him back on Domemarie-Dontilly. From there, as ordered by Napoleon, he continued his march toward Montereau.

By 1pm, Nangis had been captured and the enemy pushed back. Nangis was an important crossroad from which three roads led to the three Seine crossmgs at Nogent-sur-Seine, Bray-sur-Seine and Montereau. The Emperor was quick to make up his mind. The Allies were withdrawing. Wittgenstein and what was left of his command retreated toward Nogent while Wrede and his Bavarians headed toward Bray. Napoleon decided to pursue them only with the commands of Oudinot and Macdonald. The third road headed for Montereau, the closest of the three crossings, and was the only one that could be captured quickly. He felt that his primary effort should be made in that direction since it would give the best results, because a push in the direction of Troyes would automatically open the two other crossings to Macdonald and Oudinot.

In addition, on the right bank of the Seine, the Wurttemberg vanguard had pushed as far as Melun. On the left bank, the Austrian vanguard and left wing had pushed as far as Fontainebleau, where Allix with his 6,000 men tried to hold them at bay. If Montereau and its bridges over the Seine and the Yonne were quickly taken, these enemy forces would be cut off. The success depended on the quick execution of such a move. [16]

The plan was simple. Napoleon entrusted Victor with his fresh troops to capture Montereau.

Consequently, he pushed Victor, Gerard and 11,000 men via Villeneuve and Salins. At the same time, Pajol, Pacthod and 6,000 men attacked the Wurttemberg vanguard from Melun via Le Chitelet, Panfou, and Valence. Finally, the Emperor with Ney and 10,000 men were in Nangis, ready to follow Victor and, if necessary, support him. [17]

From Montereau, the Emperor then planned a quick march to Troyes, his force collecting Macdonald after the latter's crossing of the Semie at Bray and Oudinot after his crossing at Nogent. Moreover, Napoleon would be further reinforced by the 10,000 horse of Nansouty and Leval still in the vicinity of Montmirail.

The plan was set but its implementation would not be easy. At first, Victor moved quickly but soon Hardegg and the Bavarian Lamotte, who had deployed a few miles south of Nangis between Villeneuve-les-Bordes and Valjouan, blocked his progress. G6rard deployed the vanguard and violent encounter resulted. Villeneuve was soon taken. The battle developed favorably. Soon the Allies were forced back toward Donnemarie, and the Wiirttembergers toward Montereau. For unknown reasons, Victor then became inactive, and, in spite of his orders, he stopped at Salins although one of his vanguards had reached Surville. Some Guard squadrons pushed a reconnaissance toward Montereau.

De Segur. p. 214, says:

Chandler, p.979., is of the same opinion. He claims that Victor dragged his feet all day and stopped for the night at Villeneuve.

That dilatory conduct gave the Prince of Wurttemberg the time to draw up his men in a

strongly fortified position north of the Seine covering the town. Pajol's cavalry pushed the Prince's outposts back, but could not undertake any more forceful action until Victor condescended to appear on the scene at nine o'clock on the morning of the 18th.

Houssaye, p.73, reported essentially the same, i.e. that Victor stopped at Salins with the bulk of his troops. However, in a footnote, he seriously contested that the bridge at Montereau would have been taken that easily on the eve of the 17th saying the following:

"The emperor has strongly reproached the Duke of Bellune for not having taken Montereau

on that day. [18] If he had effectively taken the Montereau bridge on February 17, the Emperor in crossing over the next day would have cut off the retreat of Bianchi's Corps and would have taken in rear the Corps of Wittgenstein and Wrede at Bray and Nogent. The army of Bohemia would have suffered the same fate as the army of Silesia. But would have Victor, after marching and fighting the entire day, been capable of taking in a night combat, the position defended by 14,000 Wurttembergers? That is doubtful, and even more doubtful for on the next day, the 18th, it took six hours for 4 infantry Divisions, 2 cavalry divisions, and a large artillery deployment to dislodge the Prince of Wurttemberg. Or one must conclude that the irritation of the Emperor was because he thought Montereau to be occupied by only a part of Wrede's Corps, and not by the entire Corps of the Prince of Wurttemberg, or one must think, as Fain says it, that Napoleon had other grievances against Victor. The marshal had shown much softness and lack of foresight during the defense of Alsace." [19]

On the same day, Macdonald pushed back Wrede toward Bray, Oudinot pushed Wittgenstein back

to Nogent, and Allix forced Bianchi to evacuate Nemours. De Segur gives a good description of operations on the next day (pp.217 to 219):

He first learned that around 9AM, Chateau's Division, sent alone from Forges to Villaron,

had been overwhelmed; then, an hour later, Duhesme, in turn, renewing the attack, was also

repulsed; finally around twelve thirty, Gerard's Corps, coming by the road from Nangis, entered into

the line. The Empcreur could accept that lack of coordination. What was evident to him, was that

the combat badly engaged, continued; that is, the retreat of the enemy's formations adventured

toward Melun and Fontainebleau, and which were to be cut off by the maneuver, had unfortunately

taken place, and at that very moment they were escaping. Consequently, to the premature stop of

the previous evening, Victor added a reprehensible slowness to the attack of that day, and to that

second fault added a third one, by successive uncoordinated attacks he was defeated in detail.

.... the intrepid Pajol, carrying out his orders, attacking at 7AM, which attack Victor had not supported, saw his guns dismounted and his conscripts shredded to pieces by a much more

numerous enemy. He did not retreat, he still held his ground, but he had already lost 3,000 men.

Then, Napoleon's frustration reach its limit.... General Dejean informed Victor that the

Emperor removed him from command and gave it to General Gerard, and that Victor must

immediately leave the field....

.. Immediately, everything changed. So far an artillery duel had taken place, that of the Prince of Wurttemberg more numerous than ours, was crushing us.... Gerard changed that unequal combat by unlimbering the 40 guns of his reserve. Immediately the advantage became ours.... We find Napoleon unhappy about Victor's behavior and, on the spot, he relieved Victor from

command, replacing him by Gerard. [20] Soon after, on the 18th, Gerard, with the II Corps, and Pajol dislodged the Wurttembergers from the Surville plateau and crossed the Seine on their heels. It became a rout when Napoleon personally led his guns forward to the captured bridge. Then, the wounded Pajol executed a brilliant cavalry charge over the bridges through Montereau and over the Yonne, capturing the bridges before the Allies could fire the demolition charges. [21]

Schwarzenberg ordered a general retreat toward Troyes. The combat of Montereau and Victor's

failure to seize the bridge on the previous day, had given the time for Bianchi and the other compromised Allied forces to escape Napoleon's trap at the price of forced marches.

The Battle of Montereau was a hard fought affair. The Allies lost some 6,000 casualties and 15 guns. French losses were only 2,500. Wiirttemberg was in full flight on the road to Troyes by Bray-sur-Seine, where he barely preceded Macdonald on the 18th. The same day Oudinot reached Nogent, but as at Bray, the French army found the bridges destroyed and the enemy safely retreatIng toward Troyes on the left bank of the Seine. Once more, the lack of a bridging train spoiled good maneuvers and both commanders had to return the bulk of their commands to Montereau to cross over to the left bank.

Napoleon was greatly disappointed with his success in spite of the fact that Schwarzenberg; had been very roughly handled. He had expected much more, something like a repetition of Montmirail and Vauchamps. He felt frustrated because of the seven corps of the army of Bohemia, five corps had escaped completely unscathed.

At least, Napoleon had the satisfaction of seeing the Austrian commander-in-chief seek an

armistice. [22]

The Aftermath of Montereau

Now, Napoleon had to reevaluate the situation. He had planned to move directly to Troyes, but he had no way of predicting the Allies' next move. Would they concentrate there and offer him battle or would they continue to retreat? Schwarzenberg had no alternative but to withdraw toward Troyes requesting Blucher to join him at Mery-sur-Seine.

Considerable delays in crossing the Seine at Montereau afflicted the French army which lost contact with the Allies. It is only on the 22th at noon that contact was reestablished when the French columns began to appear in the plain of Troyes while, on the left, Boyer's Division chased out Blucher's vanguard from Wry-sur-Seine. [23]

That delay gave Schwarzenberg the breathing time he needed to retreat his army to Troyes. Blucher and Schwarzenberg had made their junction at Mery-sur-Seine on the 21st. However, the bridge at Mery had been destroyed and Boyer's Division of veterans from Spain prevented Blucher's crossing. [24]

On the 21st, the Emperor had ordered Mortier to fall back from Soissons to Chateau-Thierry to defend the Marne river and to keep close contact with Marmont who was in Sezanne. On that day, he once more summoned Augereau to come out of his "hibernation" and attack Schwarzenberg from the South. [25]

Late on the 22nd, in front of Troyes, the Allied Grand Army was deployed in line of battle, its

right on the Seine and its left on the village of Saint-Germain.

[26] It was too late for Napoleon to engage in an action and besides that, his army was not yet concentrated. But an action would certainly take place the next day. At least, so he thought... The Allies were more numerous than his mere 70,000. He estimated that they were probably well over 100,000 but the morale of their troops had been affected. The Wurttembergers' withdrawal had resembled a rout more than a retreat. In addition to the morale factor, the Emperor felt that the Allies were in a poor position. The river to their rear was another handicap. Blucher presented a threat on the left flank, but he was facing a solid wall of veterans from Spain, and it would take at least 24 hours before he could cross the Seine with his command. That gave Napoleon ample time to defeat Schwarzenberg. Hence, he decided to risk battle the next day and was sure he could win it.

The Allies Further Retreat

The Allied high command with its galaxy of monarchs was in turmoil in trying to define their next move. A meeting of the Allied leaders was held in Troyes on the 22nd as Schwarzenberg had deployed his troops in front of that city. The Czar and the King of Prussia, Knesebeck and others were partisans of an immediate battle, but Schwarzenberg, Lord Castelreagh, Nesselrode, Toll, and Wolkonsky disagreed. Schwarzenberg, knowing the state of morale in his army, was determined to avoid a battle and wished to continue withdrawing. He believed that Napoleon had a much greater force than he did and was very concerned about the threat that Augereau presented to his communications. In the spirit of Hapsburg military dogma, he was not willing to sacrifice the Army of Bohemia to the glory of France. Schwarzenberg's arguments prevailed and the Allies agreed to continue the retreat. Schwarzenberg had taken it upon himself to issue the orders to withdraw before agreement was reached. This infuriated Blucher who had to retrace his steps toward the Marne and resume operations there with the reinforcement of Wintzingerode and Bulow adding to his previous command.

Schwarzenberg left a cordon of troops and withdrew the bulk of the army to Vandeuvre and to Bar-sur-Aube. On the 24th, Napoleon entered Troyes and received an enthusiastic welcome. That was in sharp contrast with the ice cold reception he and his army had to suffer after the defeat of La Rothiere.

On the 24th, the French reached Vandeuvre and Bar-sur-Seine while the Allies continued their

retreat. A new demand for an armistice was made by the Allies.

Conclusion

In a few days, Napoleon, by a series of brilliant maneuvers, had inflicted heavy casualties on the Allies and forced them back to the line they held before La Rothiere. He had also concentrated a large army.

The Allies constantly received more reinforcements than Napoleon could. The large numbers were to have the last word.

[1] Correspondance No.21261, Vol XXVII, It was a new version of the famous maneuver sur les derrieres or maneuver on the rear.

Chandler The Campaigns of Napoleon, Macmillan, New York, 1966.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web."The Austrians know my way of operating too well.... and if they leave us master of the

Nogent bridge they will worry lest I should emerge on their rear in the same manner as I have done here..."

After that unexpected reconnaissance, all the symptoms of a rout were apparent in the city. Two more hours of effort and Victor would have taken the crossing on that very same evening.

... On February 18, by 7AM, full of confidence, Napoleon advanced on Victor's trail ....

he was surprised not to hear any sound of guns toward Montereau while some faint rumble

announced that Pajol had already attacked.... Around 9AM, the Emperor learned that Victor had not yet begun his attack .... Napoleon mounted his horse as Victor's cannons started firing but it was a weak sound announcing nothing decisive. Montereau was not yet in our control! The Emperor sent officer after officer to hurry the attack... he could see the opportunity fade away. His irritation increased every minute. Soon some successive reports were to increase it.

Footnotes

[2] Correspondance No.21244, 21253, 2126 1, Vol.XXVII.

[3] Schwarzenberg orders of February 11 and

13, quoted by Plotho, Vol. 111, pp. 146-15 5.

[4] Chandler, p.975, De S6gur, p.206, etc.

[5] The reason for that was simple. Schwarzenberg was fully aware of Napoleon's tactics and knew that Napoleon would not hesitate, at the first opportunity, to attack him he supported a major drive against Fontainebleau. Sure Napoleon was still far away, but Schwarzenberg unlike Blucher did not underestimate the Emperor. Consequently, the later felt that Schwarzenberg would not support any advance south of Nogent-sur-Seine as long as that city and its bridge were under French control.

[6] Correspondance No. 21236, Vol.XXVII, p. 156.

[7] Bray-sur-Seine in 10 miles west of Nogent.

[8] The order to stop the allied advance toward Paris was due to two additional factors. The first one was due to the result of five weeks of constant looting by the Allied troops, had driven beyond the limits of endurance, the French peasants. The results was that the French peasants became in open rebellion against the Allies. Stragglers were murdered, columns snipped at, small detachment attacked and even wiped out, convoys attacked and often destroyed and communications greatly affected. The second reason, a partial consequence of the first one, was that Schwarzenberg was becoming increasingly concern about his communications through the Plateau of Langres were becoming increasingly vulnerable to a possible attack by Augereau's Corps which was forming at Lyons.

[9]Schwarzenberg's orders dated February 15 and 17. Plotho, Vol. III, p. 157-8.

[10]Houssaye, p.71, Chandler, p. 978.

[11]De Segur, p.208.

[12] Ibid, p.209.

[13] Ibid, p.209.

[14] Mikhailofsky, p. 149.

[15] The Czar quickly sent a letter of reprobation to Wittgenstein.

[16] De Segur, p.212, Houssaye, p.72.

[17] Fain, 110, Plotho 111, p.211-213, ctc.

[18] Correspondances No.21 286, 21297, Vol. XXVII, p. 192.

[19] Houssaye says: "See Correspondance 21 066 and letter to Caulincourt, Lundville January 7, Foreign Ministry, fonds France 668: "Everyone agrees that the duke of Bellune does not do anything, does not go out of his house and does not take any measure to get information... We can say, that if one of Napoleon's lieutenant deserves to be blamed during these glorious days, that surely was Macdonald. By going on February 10 and 11 from La Ferte-sous-Jouarre to Chateau-Thierry has he had been ordered, Correspondence No. 21228 and 21 235, he would have cut off the retreat toward the river Ourcq to the routed Corps of York and Sacken, from which not a single man would have escaped."

[20] Victor's disgrace was of short duration see Houssaye, p.73.

[21] Chandler, p.960.

[22] In complete bad faith, Schwarzenberg asked for an armistice on the ground that agreement had been reached at Chatillon to end the war. In fact the Congress had been suspended by the Allies between February 9 and 17. Napoleon was no dupe and recognized the demand as a ruse to gain time. Houssaye p. 72, Chandler, p. 980, etc.

[23] After concentrating his command at Clifflons, BIficher had headed south to make his junction with Schwarzenberg. Houssaye, p.74. Bogdanovich, 1, 257. etc.

[24] De Segur, p.243, Mikhailofsky, p. 162.

[25] Correspondance No. 21343 Vol. XXVII, p. 224.

[26] Order of Schwarzenberg for February 22, quoted by Plotho, III, p.223.

Sources:

Correspondance de Napoleon, 32 vol., Paris 1858-70.

De Segur, Comte Philippe, Du Rhin a Fontainebleau, Nelson, Paris, date unknown.

Empires, Eagles and Lions, Vol. 2, issues 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Houssaye 1814, Pernin, Paris, 1888.

Jomini, Precis politique et militaire des campagnes de 1813 et 1814, published by Colonel Leconite, Paris 1886, Vol. II, pp. 238-9.)

Koch, F., Memoires pour servird l'Histoire de la Campagne de 1814, 1819, Paris, Chez Magimel.

Lachouque, Commandant Henri, translated by Anne S.K. Brown, Anatomy of Glory, Brown University Press, 1961.

Mikhailofsky-Danielefsky, A. History of the Campaign of France in the Year 1814, 1992 reprint by Ken Trotman Ltd. Cambridge. England.

Numerous miscellaneous notes from French Archives (Archives Guerres and Bibliotheques Nationale).

Plotho, C., Der Kreig in Deutschland und Frankreich in den Jahren 1813 und 1814, 1817, Berlin, Carl Friederich Amelang.

Sporschil, J, Die Grosse Chronik, Geschichte des Kreiges des Verbundeten Europa's gegen Napoleon Bonaparte, in den Jahren 1813, 1814, und 1815, 1841, Braunschweig, George Westerman.

von Damitz, K., Geschichte des Feldzuges von 1814 in dem Ostlichen und nordlichen Frankreich bis zur Einnahme von Paris, 1842, Berlin, Ernst Siegfiied Mittler.

Zweguintov, L'Armee Russe, Paris.

Back to EEL List of Issues and List of Lochet's Lectures

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Jean Lochet

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com