SPECIFIC PROBLEMS WITH THE CAMPAIGN OF RUSSIA

As early as the beginning of 1811 the decision to invade Russia in 1812 had been made by Napoleon in spite of the unfavorable development of the military situation in Spain.

Napoleon because of the problems in the Peninsula--where more Light Cavalry was needed--decided to increase the strength of the Light Cavalry, Hussars and Chasseurs a Cheval regiments In addition, a few new regiments were also added.

In January 1811, it was decreed to add a 10th company to the Light Cavalry regiments which effectively bring them to 5 squadrons. Then from Utrech, on October 7, 1811, another decree further increased the Light Cavalry to 6 squadrons.

However, with the exception of the 9th Hussars--which had raised its 6th squadron by November 1811--none of the regiments could raise their 6th squadrons before the beginning of the invasion of Russia.

In fact, the 9th Hussars did not keep its 6 war squadrons for a very long time. On January 8, 1812, a new Imperial decree gives the regiment a 7th squadron and break it down into 2 regiments.

The 9th Hussars which was in Alsace (east of France) kept its name and included the lst, 5th, 6th and 7th squadrons, while the 2nd, 3rd and 4th squadrons engaged in Spain become the 9bis Hussar regiment.

The 9th Hussars was inspected on January 19, 1812 by General de brigade Burthe. Burthe complains that the regiment is practically entirely formed of recruits and has very few cadres to instruct it. That did not prevent these unfortunate young men to depart for Russia.

On June 3, 1812, Napoleon insisted that all the 4 war squadrons of the Light Cavalry regiments about to depart for Russia had a minimum strength of 1050 men.

Orders were also issued to increase the strength of the Cuirassiers to 800 per regiments as well as that of the Dragoons.

Since 1807, Napoleon had desired to add lancers to his line cavalry. On June 18, 1811, a decree organized 9 regiments of Chevau-Legers-Lanciers (6 from 1st, 3rd, 8th, 9th, 10th and 29th Dragoons) 1 from the 30th Chasseurs a Cheval and the 2 regiments of Polish Chevau-Legers of the Line received lances and became de facto Lancers.

Overall that order was fully implemented as it is shown by the June returns before the crossing of the Niemen.

THE PREPARATION OF THE CUIRASSIERS FOR THE CAMPAIGN

In 1811, a commission led by the Duc de Feltre, the War Minister reexamined the types of weapons used by the different cavalry arms (Light Cavalry, Dragoons, Cuirassiers and Carabiniers). After the following letter from Napoleon, dated November 12, 1811, it was decided to give a musket to the Cuirassiers:

- I answer you letter concerning the weapons to be used by the cuirassiers and

lancers: it is an extremely important question.

It is recognized that the Cuirassiers can only use with difficulty the musketoon; however, it is also completely absurd that 3 or 4,000 of so brave men be surprised in their camps or stopped during their advance by 2 companies of voltigeurs. Therefore it is imperative to give them weapons. The cuirassiers of the royal army had musketoons which they did not carry suspended like the light cavalry but to be used as muskets ... (i.e. when dismounted, JAL)

Present me a project on that matter so these 3,000 men would not need infantry to guard their camps....

Concerning the lancers, see I fit possible to also give them musketoons in addition to their lances; if that is impossible, at least a third of the company would have to be receive musketoons...

The extensive work of the commission was sanctioned by the decree of December 25, 1811. It armed the Cuirassiers with a heavy musketoon and 1/3 of the Lancers-beside their lances-with the Light Cavalry musketoon .

The musketoons were only provided for the Cuirassiers for defensive purposes a stated in the letter from Napoleon, when in encampments or in contact with small infantry detachments. More was expected from the Chevau-Legers.

The decree stipulated that 30 men per companies of Chevau-legers were to be armed with musketoons instead of lances in order to be able to fire from the saddle and if necessary to act as skirmishers.

Another decree from Napoleon also dated December 25, 1811, addressed to the War Minister reorganized the Cuirassiers:

- The 1st Division, commanded by General Saint-Germain, includes 2nd, 3rd and 9th

Cuirassiers. Each regiment shall form a brigade with 8 squadrons. There will be 3 generals of

brigade, Bessieres, Brunot and Quennot.

2nd Division: 5th, 10th and 8th Cuirassiers. 3rd Division: 4th, 7th, and 14th Cuirassiers. 4th Division: 1st, 2nd Carabiniers and 1st Cuirassiers. 5th Division: 12th, 6th and 11th Cuirassiers.

12 pieces of light artillery will support each Division.

The 1st Lancer regiment will be attached to the 1st Division; the 2nd to the 2nd Division; the 3rd to the 3rd Division; the 4th to 4th Division; the 5th to the 5th Division.

Each Lancers regiment will be 3 squadron strong and completed to 800 men and 800 horses.

If on March 1st, each regiment of Cuirassiers has reached 900 horses, the increase of 800 Lancers per Division shall bring the strength of a Division to 3,500 horses.

You shall issue an ordinance for the service of the Lancers with the Cuirassiers.

The service of correspondence, escort, and skirmishers will be made by the Lancers.

When the Cuirassiers charge infantry, the Chevau-Legers Lanciers must be placed behind or on the flanks of the Cuirassiers to pass through the regiment intervals and fall on the infantry when routed, or, if the combat was with cavalry, to pursue it vigorously.

TRAINING OF THE CHEVAU-LEGERS WITH THE CUIRASSIERS

The decree fixing the training of the Chevau-Legers-Lancers with the Cuirassiers is dated February 15, 1812. We are going to cover only the critical points of the decree:

- Article 1: The Cuirassiers shall the musketoon

Article 2: The musketoon shall have a bayonet

Articles 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 cover the training of the Cuirassiers on foot according to the Provisional Ordinance (Ordonnance Provisoire) of the Year 13, applicable to the Light Cavalry.

Article 8: The Chevau-Legers-Lancers shall be trained to use their musketoon with the bayonet as per the Ordinance of the Year 13.

Article 9: Chevau-Legers-Lancers shall be trained to handling of the lance as per the Ordinance for Lancers dated September 24, 1811.

Article 10: The Chevau-Legers-Lancers shall have only one pistol

Articles 11 and 12 deals with other training details.

Article 13: Specifically deals with combat on foot.

The other articles deal with the service of both Chevau-Legers-Lanciers and Cuirassiers when brigaded together. Here are the main points:

- Article 14: The Divisions, brigades or regiments of Cuirassiers shall be kept in mass (i.e. concentrated for mass action and not dispersed in small detachments, JAL)

Article 15 and 16, specifies that they can not be used in detachments, vanguard, escort and the like.

Article 17: When on the move they shall not be sent as scouts, flankers or skirmishers.

Article 18: During the charges by Divisions, brigades or regiments, they shall never disperse themselves or pursue the. defeated enemy, unless it is routed infantry far away from the support from its cavalry.

Article 19: As soon as the enemy is broken and the success of the charge assured, the Cuirassiers shall stop and leave the pursuit to the Chevau-L6gers-Lanciers. ... the Cuirassiers are to reform ... to assure another orderly charge if necessary...

Article 20: Grand Guards, scouting, detachments, escorts shall only be made by the Chevau-Legers-Lanciers.

Other recommendations are stipulated in the remaining 11 articles of the Ordnance and too numerous to be considered here.

THE FORMATION OF THE GRANDE ARMEE

THE FORMATION OF THE GRANDE ARMEE

In early 1812, Napoleon began to assemble and concentrate near the Russian border, i.e. in Prussia and Poland, the forces to invade Russia, as well as the auxiliary units.

The first line consisted of 8 infantry Corps, of the Guard, and of the Reserve Cavalry.

The wings were to be protected by 2 foreign Corps (I Prussian and I Austrian).

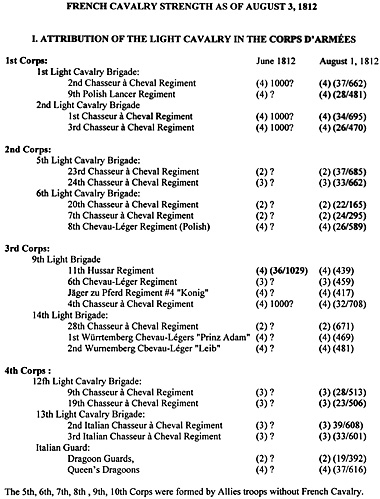

Basically, the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Corps, were mostly French but also included Allies' cavalry.

The 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th were formed by Allies troops without French Cavalry.

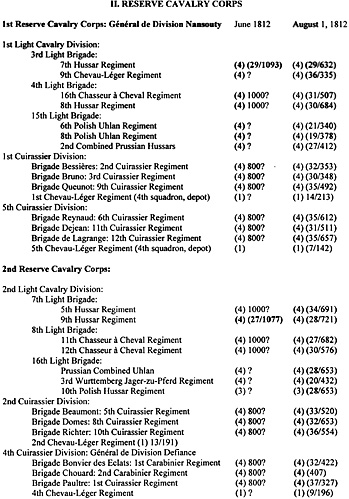

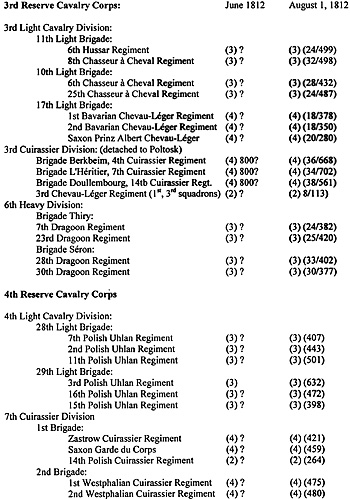

The 4 Corps of the Reserve Cavalry beside 4 regiments of French Dragoons and 2 of Carabiniers and 13 of Cuirassiers, also included 2 Regiments of Saxon Cuirassiers as well as 2 of Westphalian Cuirassiers and 1 Polish Cuirassier regiment, beside numerous French and Allies Light Cavalry regiments.

The French line cavalry regiments that had entered Russia in June 1812 were:

- 6 Hussars; regiments, 16 Chasseurs a Cheval regiments, 4 Dragoons regiments, 6 Chevau-Legers Lanciers regiments, 13 Cuirassiers regiments and 2 Carabiniers regiments.

Most of French Hussars and most Chasseurs a Cheval regiments had been completed to at least 1050 each, when they fielded 4 squadrons. Some Chasseurs regiments were at 2 or 3 squadrons only.

The Dragoons should have fielded 4 squadrons and 800 horsemen. All of them fielded only 3 squadrons with of an unknown strength as of June 1812.

The Cuirassiers were at 4 squadrons and apparently with 800 troopers.

The Chevau-Legers Lanciers were the big surprise after so many fancy decrees, etc. since they fielded only 1 squadron each! What happen to the other squadrons?)

All the above shows, that difficulties of all sorts were encountered and many could not be solved prior to the invasion of Russia.

The above does not include the Allies cavalry of which the most numerous were the Polish with no less than 16 regiments with about 12800 sabers.

All together when reserve and rear garrisons are included Napoleon had assembled no less than 675,000 men of which about 500,000 entered Russia.

About 200,000 animals entered Russia, approximately, 80,000 for the cavalry, 30,000 for the artillery and the rest for the transportation and auxiliary services.

Commandant Picard in his volume 2 of his La cavalerie dans les guerres de la Revolution et de l'Empire, quotes a French General:

- The infantry was, in general, good and well trained; the very same can be said about the

Dragoons, and of the Cuirassiers as well as the German and Polish cavalry regiments; the rest of the cavalry--the French Light Cavalry--had a great many young men and young horses. There were regiments with cadres arriving directly from Spain, which had been mounted on their way and had been on the move since 6 months. These troops which would not even have been able to survive the suffering of an ordinary campaign, were certain to be soon completely ruined in Russia. In fact, most of them did not even see Moscow and had already disappeared before the real catastrophe stroke the rest of their brothers in arm and practically eliminated them all.

Napoleon knew that the impending Russian invasion by such an extremely large army required other means than the usual preparations of a campaign, which are out of the scope of our paper.

Napoleon knew that the impending Russian invasion by such an extremely large army required other means than the usual preparations of a campaign, which are out of the scope of our paper.

From early 1812 to June as the Grande Armee was concentrating near the Russian borders, a huge supplying problems to feed such a large number of men and animals developed.

Thus a new system of requisitions was implemented. Orders were given to the Corps commanders to take with them everything that could be useful in the allied countries, foods, etc.

It resulted that:

- (1) Herds, grains, spirits, carriages were taken from Prussia and Poland. In fact Prussia suffered more damage during the short months preceding the Russian invasion than during the whole Campaign of

1807.

(2) It quickly become impossible to provide regular subsistence for all the troops. Each Corps took with it what ever was necessary without concern for what followed.

(3) Forage very quickly became very rare. Already in the beginning of June, the French cavalry fed its horses with green oat, green barley and green wheat, which caused the loss of great many horses even before the beginning of the campaign. These horses were replaced with what ever could be found locally .....

Hence, at the beginning of the campaign many horses, if they did not die, were already in a poor shape and weakened by the lack of adequate feeding before the crossing of the Niemen.

That deplorable situation was to be the cause of large losses of horses in the first weeks of the campaign.

In addition, we should further point out that the supplying of such a large army and especially cavalry with the necessary forage was beyond the capabilities of any armies of the period.

THE INVASION

THE INVASION

Napoleon intended to defeat the Russian army near the borders. The Russians did not cooperate and simply withdrew.

Consequently Napoleon was forced to follow the Russians to Smolensk with the Guard, 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 8th Corps with the Reserve Cavalry.

At the beginning of the campaign, Napoleon's main army which had included 235,000 infantry, and 60,000 horses, at the beginning of August, at Smolensk, numbered only 156,800 infantry and 30,722 cavalry.

Many young, unseasoned soldiers fell by the side and just died of exhaustion.

In early August, the 4 Reserve Cavalry Corps which strength exceeded 40,000 horse at the beginning of the campaign was reduced to only 22,000 horses.

(Doumerc Cuirassiers Division: 4th Cuirassier, 7th Cuirassier and 14tb Cuirassier Regiments and 3rd Chevau-Leger Regiment had been detached to the north flank at Olozk. They were to be the only truly organize Cuirassier formations at the crossing of the Beresina).

Only few casualties had resulted from the combat and it was because of the excessive fatigue due to the sustained daily long marches without proper rest, that the number of horsemen had been so drastically reduced.

Four weeks later at Borodino, Napoleon's main army had been reduced to 105,000 infantry and 30,743 cavalry.

During the advance from the Niemen to Moscow, the French cavalry advanced practically continuously ahead of the main army, supported when the ground required it by one or more infantry Divisions.

The generals commanding the cavalry were extremely unhappy about that procedure which was depleting their ranks much faster because the cavalry Corps marched concentrated.

That concentration considerably reduced their ability to collect forage for their horses.

Every day it became more and more difficult to feed their overworked horses. Hence losses increased.

Murat, one day complained that a cavalry charge had not been carried with enough vigor and Nansouty answered him:

- That is coming from the fact that our horses don't have the patriotism of our

soldiers; our soldiers fight without bread but our horses do no do their duty without

oat.

Caulincourt reported that General Belliard, chief-of-staff to Murat, told Napoleon who had questioned him:

- Your Majesty must be told the truth. The cavalry is rapidly disappearing; the marches are too long and exhausting, and when a charge is ordered you can see willing fellows who are forced to stay behind because their horses can't put to the gallop.

Napoleon paid no attention to these prudent observations. He wanted to reach his pray; and in his view it was evidently worth paying any price to attain that object, for he sacrificed everything to gain it.

Caulincourt, pp.68-69 (of with Napoleon in Russia), continues with an analysis of the state of Murat's cavalry:

- The King of Naples, who, like the Emperor, had constantly been nibbling at the Russians,

while doing ten or twelve leagues a day, and whose hope of success on the morrow had hindered

him from calculating his daily losses, realized his weakness as soon as he was in position. He saw with apprehension the decreasing strength of his regiments, most of which were reduced to less than half their numbers. Forage and stores of all sorts were lacking, for his forces were always in close order and on the alert. Arrangements had been made for rationing the men during the first few days, and the Cossacks were already hindering them from bringing stores. The horses were not shod, the harness in a deplorable state. The forges like the rest of the material, had been left in the rear. The greater number of them, indeed, had been abandoned and lost. There were no nails, no smiths--and no supplies of iron suitable for making nails.

Caulincourt paints a picture of the Emperor (and of Murat) that is not very flattering. Both were gambling everything for a decisive battle. Both were completely by the human tragedy that began to unfold and were ready to sacrifice everything for it including the precious cavalry.

Unfortunately, the very same conditions continued to prevail.

Here we have to quantify the length of the marches:

Since a French league is equivalent to 2,400 paces or 2.76 miles, we are speaking here of 28 to 33 miles a day, (or 45 to 53 kilometers a day) under very adverse conditions.

Napoleon continued his pursuing the retreating Russians at an exhausting pace, ignoring the need for his army to rest.

The results of pursuing such a policy were devastating by any standard. But, as Napoleon did not appear to be concerned with the increased strategic consumption.

Yet, the losses steadily increased. Then, came Borodino, the stay in Moscow and the disastrous retreat.

Back to EEL List of Issues and List of Lochet's Lectures

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Jean Lochet

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com