Bonaparte after Brumaire and the Operations in Germany and

Italy

Bonaparte after Brumaire and the Operations in Germany and

Italy

Bonaparte at his return from Egypt with the prestige of his triumphs, found France in a sorry state. Within a month he ousted the corrupted and inept Directory and, on the 18th of Brumaire, Year VIII of the Republic, (November 9-10, 1799) established a three-men government, the Consulat with himself as First Consul. He found the finance in shamble and the army in an equal state of disorganization.

He started the reforms immediately, but France was at war and Bonaparte had to face the Second Coalition.

The military situation was not encouraging as the French had been ousted from Italy and were barely holding in the East.

Fortunately, the victories of Stockach (May 3, 1800) and Meskirch (May 5) followed by that of Hochstadt (June 19) won by Moreau over the Austrians under General Kray forced the Austrians to suspend the hostilities until November.

Bonaparte formed some Army Corps, reorganized some units and formed an Army of Reserve.

In May 1800, he led the Army of Reserve across the Alps, occupied Milan on June 2.

Bonaparte forces numbered 60,000 against 72,000 Austrians under Melas. In a maneuver on the rear, Melas was forced to fight at Marengo where he was defeated. The next day Melas signed an armistice.

In Germany, the armistice ended and the Austrians under Archduke John (he had replaced Kray), resumed their offensive but were decisively defeated at Hohenlinden on December 3 by Moreau.

That was the end of the Second Coalition. Austria signed the Peace of Luneville in February 1801 and England the Treaty of Amiens signed on March 27, 1802.

Now the First Consul had a freer hand to carry his reforms.

The Second Coalition included Great Britain, Russia, Austria, the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, Naples, and the Papal state.

Hostilities had started in Italy in November 1798 and the Napolitan army, as well as that of the Papal state were quickly overran..

Austria had declared war on March 12, 1799. Jourdan had already crossed the Rhine with an underpowered command.

The Directory had assured Jourdan that he would have 100,000 men provided with an adequate park of artillery, magazine of provisions etc.

His left flank was to be protected with an army of observation of some 38,000, while Massena with some 24,000 men was to operate in Switzerland and protect his right.

But at the opening of the campaign, Jourdan's command included only 36,994 men and the army of observation supposed to protect his left flank was only 10,000 and much too weak to do anything significant.

Jourdan should have resigned as he lost his reputation in the process.

The Archduke Charles had a huge superiority. The total of his forces against Jourdan on the Danube and Massena in Switzerland was 165,000. He faced Jourdan with some 80,000 troops: 53,900 infantry and 23,000 cavalry. The rest was sent against Massena in Switzerland.

Jourdan advanced through the Black Forest and soon came in contact with the more numerous Austrians.

He was speedily defeated by Charles on March 21 at Ostrach and again on March 27 at Stockach, while Massena was repulsed on March 23 at Feldkirch. Jourdan retreated in haste.

Massena was further defeated at the first battle of Zurich. On April 5, the Austrians under Kray won another victory at Magnano and made his junction with Souvarov and his Russians. Together they swept the French out of Italy.

Souvarov in Switzerland was defeated by Massena at the second battle of Zurich on September 26-27.

BONAPARTE'S MILITARY REFORMS

Bonaparte inherited from the Directorate several armies more or less independent from one another of unequal values.

By a series of reforms, in a very short time, he formed an extraordinary and homogeneous block that became the Grande Armee.

- (1) regiments were consolidated in standard units -- at full strength --

by eliminating the small and numerous undersize formations previously found

in the armies of the Directoire.

(2) brigades and Divisions were standardized to include only cavalry or infantry and formed into Army Corps which included from 2 to 4 infantry Divisions, a brigade or Division of cavalry and some 30 to 60 guns and a detachment of engineers.

(3) The cavalry went through a complete overall. The surplus of cavalry was reorganized in a Cavalry Reserve numbering some 22,000 horsemen.

(4) Artillery was evenly distributed among the Divisions and an Artillery Reserve was also formed which included mostly 12-pdrs.

(5) The ultimate reserve was formed by the Consular Guard which became the Imperial Guard in 1804.

THE GRANDE ARMEE IN 1804

The Army was reorganized in 11 Corps plus the Army of Italy under Massena which kept the old Divisional organization.

The Grande Armee was under the direct command of a single generalissimo: Napoleon Bonaparte assisted by an extraordinarily efficient staff. That fact alone ended the sources of the problem of non unified commands that had plagued the armies of the Revolution.

The treaties of Luneville and Amiens gave the period of quiet necessary to prepare what we can call the "Imperial Epic". The training at the huge Camp of Boulogne did the rest. Bonaparte became Emperor in December 1804.

The changes brought up by the introduction of the Army Corps system and of a unified command

The Grande Armee was no longer a conventional army force. The changes it brought to the art of warfare was far beyond the introduction of new tactics.

In 1804-1805, the Austrian and Russian armies of 1805, were "regimental" armies on the eighteen-century pattern. They had no permanent or even semipermanent subdivisions like the brigade, Divisions and Army Corps.

For the Allies, terms like columns, corps, Divisions, wings or brigades signified no more than an ad hoc arrangements of battalions or regiments.

On the approach to the field of Austerlitz, the French &migr6 General Langeron, now in Russian Service - but who had been in French service and knew the advantage of the Divisional system - was astonished to see that the chiefs were not given the slightest opportunities to know their units. He describes the situation:

- In these five marches the individual general never commanded the same

regiments from one day to the next. . . " (Quoted by Duffy in

Austerlitz, p. 26.)

Commanders were shifted around much too often and the armies cohesion suffered.

The old command system lacked the decentralization in command possible with the Corps System, each with its own, adequate, trained staff, capable of quickly issuing orders - through the chain-of-command -- down to the battalion to implement the general orders of the commander-in-chief.

Hence the Corps system was capable of better control than the old system. With the new system, the Army commander had only to issue orders only to his Corps commanders, the Corps commanders pnly to their Divisions commanders, etc.

At Austerlitz, we see the Napoleon controlling the development of the battle by issuing orders to the Corps (or task force) commanders at the critical times, but leaving the detail of the application to them.

In contrast, the Allied armies was divided in 8 different columns. Every column commander had received detailed orders on what they had to do. But that done, Kutusov was completely unable to control his army after the French appeared unexpectedly on the Pratzen with the exception of the 4th column that was near by, more or less under his direct line of sight. The rest of his army operated on their own for the rest of the battle with the result we know.

THE ARMIES PRIOR TO THE INTRODUCTION OF THE CORPS SYSTEM

Although the major states had military establishments numbering over 200,000, filed armies had been small and a few exceeded 50,000.

Frederick the Great commanded 64,000 at Prague; 50,000 at Hohenfriedberg but less than 50,000 in all his other battles. The Austrians had 84,000 at Leuthen, 80,000 at Hochkirch and 64,000 at Prague but less than 50,000 in the other battles.

During the Wars of the French Revolution battles were fought with much smaller effective than that of the Empire. Very few battles were fought with effective above 50,000 on each side and most were far below that number.

But in contrast, during the wars of the Empire, very precisely because of the more versatile Corps system, Napoleon commanded and controlled more than 100,000 in several of his battles: 175,000 at Smolensk; 110,00 at Lutzen 175,000 at Bautzen; 167,000 at Wagram; 160,000 at Gross Gorschen, 133,000 at Borodino 100,000 at Dresden and 195,000 at Leipzig.

The Allies, after they also introduced the Corps system, or variations of it, also became capable of commanding and controlling larger armies. Kutusov had 120,000 at Borodino. Bliacher had 80,000 at the Katzbach, 100,000 at Craonne, 128,000 at La Rothi6re. At Leipzig, the Allies concentrated no less than 320,000.

Obviously a revolution of some kind had taken place.

The reason that large armies in the old system could not be effectively commanded and controlled once fielded was due to several reasons.

- (1) The Commander-in-Chief staff was very often insufficient and lacked sufficient ADCs to carry a multitude of orders to the different ad hoc subdivisions composing the army. Consequently, an army operated in single, fairly close and compact bodies directly under the eyes of the commander-in-chief.

(2) Since their cavalry was distributed among the troops, these armies lacked the strategic versatility due to the lack of long range reconnaissance forces. In 1805, the unfortunate Mack at Ulm, had no idea of what was about to take place until it was too late.

(3) These armies depended on a very large supply train system, and since armies were concentrated, it was very difficult to fit such a large train in relatively narrow frontage. The dependence on the supply train considerably slowed the rate of advance of such armies.

(4) The rigid deployment of the linear tactics in which an army was deployed in two extended lines acting in concert with cavalry on the flanks prevented the concentration of large armies since these lines had to be controlled as a whole.

THE IMPULSE SYSTEM

With the new Corps system (and of independent Divisions) defense and offensive actions were no longer the effort of an entire line under the direction of a single commander attempting to control the movement and actions of an entire army.

The attacking or defensive actions but were broken up in a series of individual actions or series of "impulses" on the enemy position. These impulse actions were now the responsibility and under the control of the subcommanders who controlled Divisions and Corps.

Hence, the role of the commander-in-chief was greatly simplified and had no longer the task of commanding and controlling directly his troops. He was now in a position to hand out the control of larger forces to individual subcommanders.

The introduction of the organization by permanent brigades and Divisions was the basic ingredient of the flexible French tactics based on the battalion column for maneuver and the introduction of was is sometimes called the impulse system.

The Army Corps System

The idea of the Army Corps was not new, it had been experienced by Hoche, Moreau and others as early as 1795-6. For instance Moreau in 1795, organized his army Rhin-et-Moselle in 3 commands: Right Wing under General FA-rino (25,018), Center under General Desaix (27,292) and Left Wing under General St.Cyr (19,271).

These "wings" and "center" although not called Army Corps had the strength of a Napoleonic Corps and operated on a wide front under the command of a single General: Moreau.

Moreau had divided his army in 3 separate Corps. Napoleon, like Moreau, in all his campaign also integrated his Corps under a single command. The difference was that now instead of single army, Napoleon integrated the bulk of the French army on a given theater of war into a single command.

With the Grande Armee operating by Corps under a single commander backed up with an elaborate staff, Napoleon introduced something far more important than tactics. He introduced a strategic system allowing a general-in-chief to command and control many more troops than before.

The system was to be enthusiastically accepted by the Prussian after 1806, the Russians after 1807 and less so by the Austrians in 1809.

OPERATING AN ARMY BASED ON THE CORPS SYSTEM

Napoleon's concept of warfare was based on principles outlined by Bourcet's and others which recommended to move troops on a wide a frontage.

That was in sharp contrast with the strategic concept of other countries which, in 1805-1806, moved troops on a close frontage.

The new strategic concept was to seek the enemy to force him to a decisive battle, as quickly as possible.

Consequently the Grande Armee, moved his Corps on a wide frontage.

In 1806, at the beginning of the Campaign against Prussia, the bataillon carre had an initial frontage of 200 kilometers [125 miles] soon reduced to 45 kilometers [28 miles] to go through the Thuringerwald and then re-expanded to 60 kilometers [38 miles] during the advance to Leipzig.

That advance was carried on several axis.

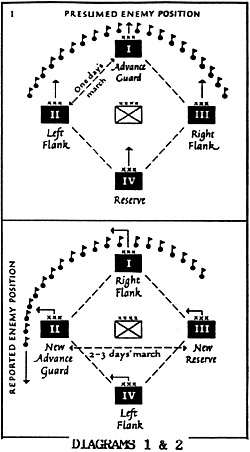

The principle of the bataillon carre shown on the diagrams was simple. It consisted in moving Army Corps over wide distances and wide frontages in a loosely drawn but carefully coordinated formations within support distance of each others. Our example (Diagram 1) shows 4 Corps moving forward at one day's march from each other, Corps #1 is the advance guard, Corps #2 and #3 are respectively the left and right flanks while Corps #4 is the reserve. The formation is screened by Light Cavalry from the Cavalry Reserve which has for primary mission to seek the enemy20.

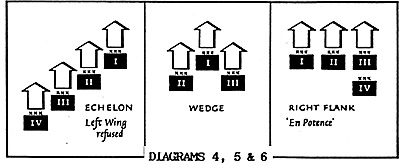

Then Diagram 2 shows the changes after the cavalry screen had located the enemy on the left flank, etc. So, it did not matter where the enemy was discovered. If ahead the Advance Guard would engage the enemy. If on the flank, like at Jena, a flanking Corps (that of Lannes) would do the initial pinning. Diagrams 4, 5 and 6 show other strategic formations used in other circumstances, always with a cavalry screen on an advance on a wide front. But the location and progression of the Corps were carefully controlled and based on the same principles.

Then when the enemy was discovered and a decisive action was about to take place, Napoleon ordered the nearest Corps to make contact with the enemy and pin him down on the present location so the rest of the army on the eve prior to the battle the different Corps were assembled.

Diagrams

Diagrams

The principle of the batallion carre shown on the diagrams was simple. It consisted in moving Army Corps over wide distances and wide frontages in a loosely drawn but carefully coordinated formations within support distance of each others. Our example (Diagram 1) shows 4 Corps moving forwaxd at am day's march from each other. Corps #1 is the advance guard, Corps #2 and #3 are respectively the left and right flanks while Corps #4 is the reserve. The formation is screened by Light units from the Cavalry Reserve which has the primary mission to seek the enemy.

Then Diagram 2 shows the changes after the cavalry screen had located the enemy on the left flank, etc. So, it did not matter where the enemy was discovered. If ahead the Advance Corp would engage the enemy. If on the flank, like at Jena, a flanking Corps (that of Lannes) would do the initial pinning.

Diagrams 4, 5 and 6 show other strategic formations used in other circumstances, always with a cavalry screen on an advance on a wide front. But the location and progression of the Corps were carefully controlled and based on the same principles.

Then when the enemy was discovered and a decisive action was about to take place, Napoleon ordered the nearest Corps to make contact with the enemy and pin his down on the present location so the rest of the army on the eve prior to the battle the different Corps were assembled.

What was a French Corps?

An army Corps was a miniature army of all arms and strong enough of engaging and resist if necessary an superior enemy for a certain time until an other Corps would come to the rescue.

In some instances, the apparent weakness of the French force immediately engaged tempted the enemy to move forward to achieve its destruction.

This was the case on October 13, 1806 at Jena, when the Prussian Prince Hohenlohe believed, after Lannes had crossed the Saale to occupy an exposed position on the Landgrafenberg, that he was dealing with an isolated flank of Napoleon's army.

Consequently, he moved his troops on a leisurely fashion sure to win an easy victory on the next day. The trouble was that during the night a much large French force had materialized.

How a French Corps Operated

(1) The Corps commander had received a clear and precise mission and seldom detailed orders on how to do it. He was informed on the movement of the army as a whole, and who he was to support, etc.

(2) The location of the Emperor headquarters was given.

(3) The Corps commanders were to inform Napoleon on the location of their own headquarters so they could contacted.

A good example is provided by the order from Berthier to Davout on October 7, 1806, prior to the Battle of Auerstadt:

- "The Emperor orders, Marshal, that you move your headquarters during

October 7 to Lichtenfels. Your 1st Division will camp around that town; your

two others between Bamberg and Lichtenfels in such a way that tomorrow the

8th, your Corps can be concentrated in order to battle in front of Kronach in

a position to support Marshal Bernadotte, who should during the 9th reach the

Saale.

I inform you that the right of the army, leaving Bamberg, will occupy Bayreuth on the 7th and will be at Hof on the 9th. It is composed of the Corps of Marshal Ney and Soult.

The center will occupy Kronach. It will move via Lobenstein. It is composed of your Corps and that of Marshal Bernadotte, of the greater part of the reserve, and of the Imperial Guard...

The left, leaving Schweinfurth, is directed on Coburg, and from their to Grafenthal; it is composed of the Corps of Marshal Lannes and Augereau.

Headquarters is at Bamberg. It will be on the 8th at Lichtenfels...

From Operations du 3eme corps, 1806-1807.

The Implementation of Orders by the Corps Commander

To implement his orders the Corps commander had his own Staff.

The Corps commanders transmitted their orders to their Divisions which operated as per rigid principles.

The Light Cavalry attributed to their Corps was sent ahead of the Corps, etc.

The Corps commander knew the capabilities of each of Divisions commanders, brigadiers, etc. and the capabilities of his troops that had been trained as per his instructions and under his supervision.

The Corps commander staff included a number of ADCs and often one or more "spare" generals and capable ADCs.

Each Division and brigade had also their own small but adequate trained staff.

The result was a homogeneous and efficient military unit.

Napoleon's Central Staff System

We only cover the single aspect of Napoleon's complex staff system that concern us directly. That is the part of the Staff that operated under Berthier to coordinate all the Grande Armee movements as per Napoleon orders.

An important point helps to understand the "secret" of Napoleon's system of warfare, is the speed at which they were interpreted by Berthier, written, transmitted and carried out.

The orders themselves were carried out by ADCs on an average speed of 5 1/2 miles an hour, a speed that had not changed for many years.

But these orders were carried out on the average in less than 2 hours between reception and execution.

| TRANSMISSION AND EXECUTION OF NAPOLEON'S ORDERS ON OCTOBER 11-12, 1806 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORPS | LOCATION ON THE NIGHT OF OCTOBER 11 | DISTANCE FROM HQ (IN MILES) | DEPARTURE OF ORDER | ARRIVAL OF ORDER | MOVEMENT STARTS | |

| Murat | Gera | 19 | 0400 hrs | 0715 hrs | 0900 hrs | |

| Bernadotte | Gera | 19 | 0400 hrs | 0715 hrs | 0900 hrs | |

| Davout | Mittel | 4.5 | 0500 hrs | 0600 hrs | 0700 hrs | |

| Soult | Weida | 11 | 0400 hrs | 0600 hrs | 0700 hrs | |

| Lannes | Neustadt | 8.5 | 0430 hrs | 0600 hrs | 1000 hrs | |

| Ney | Scleiz | 12 | 0300 hrs | 0530 hrs | 0600 hrs | |

| Augereau | Saalfeld | 20 | 0530 hrs | 0815 hrs | 1000 hrs | |

The time between the arrival of order and execution is the time that was required to interpret the order and transmit the order to the different Divisions, artillery and cavalry they were also somewhat distant from the Corps Headquarter.

So, in the Battalion carre system, the interval from the time the order was issued to the moment it was carried out averaged 4 hours. That was a huge improvement over what other armies could do and combined with the marching capabilities of the Grande Armee contributed to Napoleon flagrant successes in the field.

Overall the Allies were very far to match Napoleon's staff efficiency as well as the speed in the transmission of orders but that is another story.

Berthier, who had already been Napoleon Chief-of-staff in Italy back in 1793 and had accompanied him in that function in Egypt and in Italy in 1799, was the man behind Napoleon's efficient staff. In 1815, Soult was Napoleon's Chief-of-staff and committed many blunders in the transmission of orders.

Differences and similarities between the Revolutionary Divisions and the Empire Corps System

There is a great deal of similarity between the de Broglie's (and the Revolution's) permanent Divisions.

The permanent Divisions were the "ancestor" of the Empire's Army Corps. However, there was a great deal of differences.

- (1) The main one is in the effective. The permanent Divisions seldom

reached the effective of the Army Corps.

In many instances, they lacked the strength of the army Corps to carry out a given mission and could not, like the army Corps, sustain a full day combat with superior forces. In other words, they lacked the standing power of the Army Corps.

(2) The Revolutionary Divisions (and the brigades part of them) included a cavalry detachment ranging from a few hundreds to several thousands. There again, the Army Corps, was more versatile since the attribution of cavalry was variable and not permanent. It depended on the mission attributed to the Corps. The consequence of that was the constitution of an extraordinarily efficient cavalry Reserve. A subject in itself.

Cavalry was not attributed to Army Corps on a rigid basis but in function of the mission given to an army Corps and was attributed to Divisions (or even brigades or task forces) when necessary. Colonel Elting, p. 49, brings up an important point:

The cavalry attached to the Divisions often was used up early in the campaign; the average general didn't know what to do with it or how to take care of it. By 1797, commanders as dissimilar as Hoche, Napoleon, and Moreau were going back to separate divisions of infantry and cavalry, each with its own artillery. Napoleon was forming Divisions of three brigades, one of them light infantry."

There is also another major differences between an army Corps and a Division.

The Division had a tendency to occupy too large of a frontage for its effective and they had to be grouped in armies, which by themselves were closer to the Empire's army Corps than the Division. Colonel Elting p. 49, makes more comments on the Revolutionary Division:

- ...Especially when understrength, as they usually was, a Division was big

enough to get into trouble but sometimes not big enough to get out of

it...

That also led Generals like Moreau to group Divisions in makeshift army Corps like the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse.

Conclusion

The lineage between the permanent Divisions introduced by de Broglie during the Seven Years and perfected before 1789 and during the Wars of the Revolution has been established.

The Corps system revolutionized the art of war and hence, the new system allowed more numerous troops to be moved much faster than before without losing command and control.

That was the main achievement of the chain of events started during the Seven Years War. It was a revolution in strategy which became only possible with the development of an important staff system similar to Napoleon's huge Imperial Staff and Headquarters that directed the Grande Armee.

Perhaps wargamers instead of concentrating almost exclusively on the difference between the French tactics and that of their opponents should somewhat concentrate more on the command structure of opposing armies and on the speed of the transmission of orders, etc.

As Chandler says it in his Dictionary of Napoleonic Wars: "All in, the corps d'armee system was one major factor in Napoleon's success..."

Additional Info

The Second Coalition included Great Britain, Russia, Austria, the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, Naples, and the Papal state. With the exception of Russia and Austria, the coalition lacked substantial land forces. Austria and Russia alone were to bear the land fighting.)

Hostilities had started in Italy in November 1798 and the Neapolitan army, as well as that of the Papal state were quickly overrun. Austria had declared war on March 12, 1799. Jourdan had already crossed the Rhine with an underpowered command (The Directory had assured Jourdan that he would have 100,000 men provided with a park of artillery, magazine of provisions etc. His left flank was to be protected with an army of observation of some 38,000, while Massena with some 24,000 men was to operate in Switzerland and protect his right. But at the opening of the campaign, Jourdan's command included only 36,994 men and the army of observation supposed to protect his left flank was only 10,000 and much too weak to do anything significant. (Jomini, Vol,XI, p.96.)

Jourdan should have resigned as he lost his reputation in the process. The Archduke Charles had a huge superiority. The total of his forces against Jourdan on the Danube and Massrna in Switzerland was 165,000. He faced Jourdan with some 80,000 troops: 53,900 infantry and 23,000 cavalry. (Phipps, Vol.V. p.35.)

The rest was sent against Massena. He advanced through the Black Forest and soon came in contact with the more numerous Austrians. He was speedily defeated by Charles on March 21 at Ostrach and again on March 27 at Stockach, while Massena was repulsed on March 23 at Feldkirch. Jourdan retreated in haste. Massena was further defeated at the first battle of Zurich. On April 5, the Austrians under Kray won another victory at Magnano and made his junction with Souvarov and his Russians. Together they swept the French out of Italy. Souvarov in Switzerland was defeated by Massena at the second battle of Zurich on September 26-27.5 (5. After that defeat, Souvarov was recalled to Russia by the Tsar Paul the 1st.)

Cavalry was a variable force, and more cavalry could be attributed to a Corps if necessary or part of the cavalry was withdrawn from a Corps. We have to be careful with our wording. When we say variable forces of Light Cavalry to the different army corps, that means that the cavalry ranged from one half regiment to a full Division that is 2 to 20 squadrons (and, on some occasions, even more). For instance in 1805, the 5th and 7th Corps (Lannes and Augereau) each had only 1 Light Cavalry regiment, the 2nd and 3rd (Marmont and Davout) had 4. Massena who commanded the Army of Italy had for 5 infantry Divisions an important mass of no less than 68 squadrons. D'Espagne Light Cavalry Division formed his vanguard with 5 regiments and a battalion of converged grenadiers.)

Finally, the Corps commander had to feed back information to the commander-in-chief.

- ..."In an army, the constant unit... is the Division. It is ordinarily composed of two brigades, each of two regiments, and sometimes of three; and it has, besides, two batteries of artillery and a corps of seven or eight hundred horse. It has a complete administration it is an army on a small scale: it can act separately, march, subsist and fight; or it can come with ease to take the part assigned to it in line of battle."

It was thus that the French army was organized in our first and immortal campaigns in Italy, and also some years afterwards.

Back to EEL List of Issues and List of Lochet's Lectures

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Jean Lochet

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com