The tactics were very simple. They ignored all the subtle maneuvering and obeyed a general principle that overrode everything else:

- "Attack. all out attack. quickly and completely."

Cavalry

For speed in attack and surprise i.e. to constantly dominate the enemy. the French cavalry grandmasters based their actions on two principles:

- 1. Concentration under one direct command all the forces so the cavalry

commander could strike quickly the assigned objective with the maximum

strength possible.

2. Use of simple evolutions and attack procedures to avoid errors and and be executed without hesitation.

Time is important! If an order is to be repeated, time is wasted and the opportunity may have disappeared as well as the supreme advantage of attacking first.

PRACTICAL IMPLEMENTATION AT THE BRIGADE AND DIVISION LEVEL

PRACTICAL IMPLEMENTATION AT THE BRIGADE AND DIVISION LEVEL

The basic phases of a cavalry combat were:

- 1. IN AWAITING POSITION: The cavalry adopted a formation per regiment en masse

i.e. in close column by deployed squadrons one behind the other.

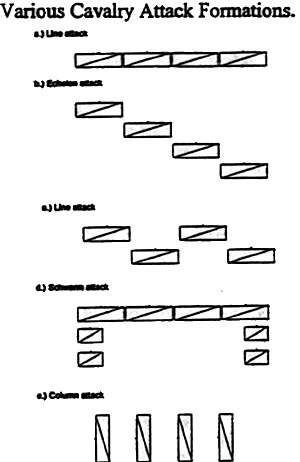

2. COMBAT FORMATIONS: The basic combat formation was the line.

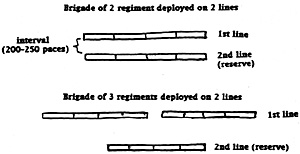

For combat a brigade or a Division was deployed in 2 lines.

The first line was to deliver the attack and the second was the reserve. The two lines were deployed either one behind the other or in overlappping echelons.

With a Division including 3 brigades, 2 brigades were placed on the first line and the 3rd on the second line.

With a brigade with 3 regiments. 2 were placed on the first line and the 3rd on the second line.

3. THE CHARGE

3. THE CHARGE

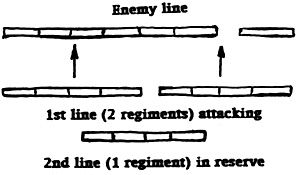

The first line was to charge -- straight ahead.

The charge was always carried out deployed in line (or in echelons) but not necessarily with the full line. The enemy could be probed with a regiment or a brigade. Then, the commander would evaluate before launching a new echelon, the result obtained by the first one in order to engage only the necessary units. So the order given to attacking force was very clear:

- "Here is the objective to strike. Charge home without worrying about

your flanks and run over everything."

Only one objective was assigned: strike the enemy like lightning and break them!

If the first fraction was repulsed, a second one was launched. And if that one was also repulsed, then the commander himself would strike like at the combat of Hoff confirmed by Murat's report:

- "The cuirassier regiment launched first was repulsed as well as Colbert's

brigade, but I was there; I vigourously charged forward with the Division and

everything was run over."

4. THE SECOND LINE

The second line was the reserve and was to assist the first line.

On occasions, it prevented flank attacks. It had to be ready to pursue the defeated enemy.

That reserve followed the first line to a certain distance to assist it without risking to be thrown back if the first line was repulsed. The distance between the first and second line was 200 to 250 pas (paces).

5. RALLYING AND REFORMING

After the charge, the cavalry fell back to the rear as quickly as possible to reform on 2 lines so to be in a position to quickly renew an attack.

So was the way an isolated cavalry brigade or Division was fighting and had most of the time infantry as a support. to allow it to rally if necessary. But in a large battle, it was relatively rare to engage on a decisive point such relatively small forces. Preferably larger forces were used in such cases.

COMBAT TACTICS: CAVALRY FORCES LARGER THAN THE BRIGADE OR DIVISION

When in a larger battle a decisive blow was planned against the enemy,

several Divisions were concentrated as -oer the above principles. that is also

on two lines under a single command (usually Murat),. each echelon flanking

the other.

When in a larger battle a decisive blow was planned against the enemy,

several Divisions were concentrated as -oer the above principles. that is also

on two lines under a single command (usually Murat),. each echelon flanking

the other.

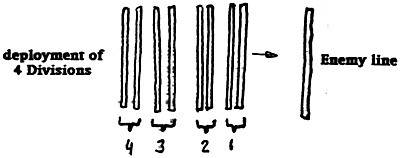

1. THE DEPLOYMENT

The deployment was as it follows:

As a first echelon, one Divisions on 2 lines. Then behind it on one of the flanks. A second division also on two lines. A third Division, behind the first line, also on two lines. Finally, the fourth Division, if it was available, was deployed behind that large formation also on 2 lines. So in such an instance, the cavalry cold often be deployed in 4, 6 or 8 successive lines depending on the number of units concentrated.

2. THE CHARGE

Except in exceptional cases like a Eylau, Ratisbonne, Waterloo. etc. were the charges were made in columns for lack of space, the usual combat took place as it follows.

The first echelon carried on the attack, and if successful, started to pursue the enemy supported by the other echelons at proper distances.

If the first echelon was repulsed, the second echelon moved forward to reestablish contact with the enemy and allow the first echelon to fall back to the rear to reform on two lines.

If the second echelon was not sufficient, the third one intervened, and finally the fourth one, so each each defeated echelon would fall back to the rear to rally and reform on two lines to renew the attack if necessary.

So the combat took place in a series of efforts given by echelons flanking each others -- each of them forming an independent unit -- but each line was still under the control of a single commander.

In fact, such actions, because they were separated on the right or on the left had a tendency to give back some independence to the individual Division commanders and prevented the single commander the control of the combat.

When the mass of cavalry reached 3 or 4 Divisions, the Emperor gave the command of that de facto corps, a commander of his own choosing, but the combat still took place as outlined above.

EVOLUTIONS

EVOLUTIONS

We have outlined how charges were carried out. Now, let us see how some simple formations allowed breaks through. deployments, flank attacks, the means to counter that of the enemy and finally the rallyment.

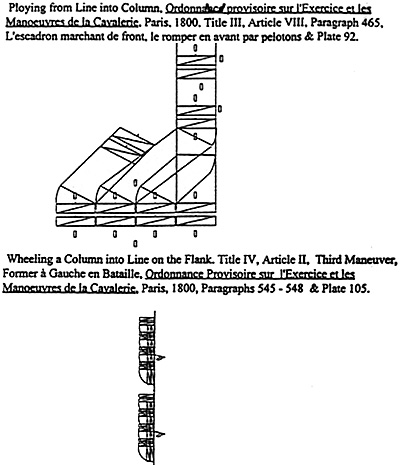

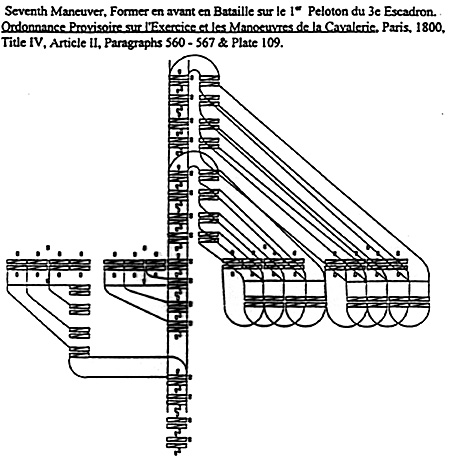

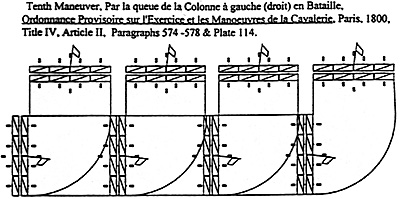

For the breakthroughs and deployments, the squadrons, having most of the time to go through some gaps to move forward, had to reduce frontage by forming columns of platoons, then redeploying ahead in line and charged. When it was necessary to move on the right or left of the line, the squadrons also formed in columns of platoons and refaced forward by either successively moving left or right par platoon, or the change of direction by the column heads and by a forward to redeploy into line.

During the Empire, the change of front were seldom used as too slow and too complicated.

FLANK ATTACKS

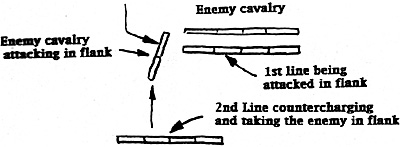

To counter a flank attack, the maneuver was very simple and consisted in moving the second line (or part of it) in good order, forward straight ahead. Consequently, that was now the turn of the enemy to be taken in flank, which was often disorganized and at a disadvantage because in order to make its flank attack, it had had to make some successive quarter-wheels.

Flank attacks were made to either relieve a defeated friendly line or

to initiate combats on several points at the same time.

In the first case, i.e. to relieve a defeated friendly line, a flank

attack was almost always successful since it was carried on a

disorganized unit with tired horses because of the prior combat and

were taken in flank or the back by fresh cavalry.

In the first case, i.e. to relieve a defeated friendly line, a flank

attack was almost always successful since it was carried on a

disorganized unit with tired horses because of the prior combat and

were taken in flank or the back by fresh cavalry.

In the second case, it was a different story as it was practically impossible to take the enemy in flank by breaking through its center line. Such a maneuver could not be carried out 99% of the time. That type of flank attack had for main objective to confuse and deconcerter the enemy by attacking it on several points.

RALLYING

The rallying was carried on as per the following principles:

- 1. If defeated the cavalry was failing back quickly to the rear

behind the support echelon (infantry or cavalry) to quickly reform on

two lines, and then moving forward to resume the attack if necessary.

2. If the enemy had been defeated, rallying was carried on the most forward echelon and the pursuit actively carried on by the second line (reserve) supported in turn by the reformed victorious echelon.

Quick rallying was a very important maneuver since victorious or defeated, the line was broken after the impact, and -- ONLY -- regained its initial power by reforming and by going back under the control of its commander.

The battle reports of the period have a tendency to prove that the squadrons were well versed in quick rallying.

CONCLUSION

The combats evolutions and tactics were so easy and simple to apply

that they could be carried out with horses of relatively average

training and of lesser blood and with horsemen of mediocre abilities.

The combats evolutions and tactics were so easy and simple to apply

that they could be carried out with horses of relatively average

training and of lesser blood and with horsemen of mediocre abilities.

The irrefutable proof is given by the great cavalry battles carried on by the poorly trained French cavalry in 1813, 1814 and 1815. At that time the French cavalry was facing the well mounted European cavalry mostly numbering many veteran horsemen in its ranks. On the contrary, the French cavalry after the huge losses of the retreat of Russia, was in the process of reforming and practically, with the exception of that of the Guard, had only conscripts in its ranks, but in spite of that consistently defeated the enemy squadrons.

The secret of these successes is easily explained. The speed and the

audacity on the attack were the two main factors. To obtain the speed

the illustrious cavalry commanders had understood that only the

simplest movements had to be used to be understood without errors and

lost of time.

Unusual Cavalry Tactics and Tricks: Cavalry vs. Infantry and Artillery

Some unusual cavalry tactics are, on occasions, found in many battle

reports and first hand accounts and can be useful to wargamers eager to

apply real Napoleonic tactics in their tabletop battles.

Some unusual cavalry tactics are, on occasions, found in many battle

reports and first hand accounts and can be useful to wargamers eager to

apply real Napoleonic tactics in their tabletop battles.

1. ARTILLERY BATTERIES

As a general rule, cavalry avoided to attack an artillery battery or position frontally.

If ordered or forced to do so, the cavalry would do so in skirmish or open order. It was not important to maintain good order when attacking artillery, but was important to avoid the effect of canister, which became murderous at short range (about 300 yards). So the assaulting cavalry would normally gallop the last 350 yards or so.

When sent to attack artillery in position, cavalry would normally make an approach from the rear or flanks often in open order or to the opposite side to the position of any infantry or cavalry in support. When the enemy support was cavalry, the approach would be made most of the time in echelon.

At Austerlitz, the 5th Chasseurs a cheval took an 8-gun battery by an attack on the rear.

During the 1814 Campaign of France, in March 1814, a cavalry force of chasseurs a cheval and lancers came upon a battery of 18 Russian guns near St. Dizier. 1 squadron of chasseurs charged in skirmish order at the gallop the front of the battery and at a distance of about 350 feet (100 meters) from it the wheeled to left and right, then charged on both flanks. At the same moment a squadron of lancers in open order charged the front. The battery was taken and eliminated.

2. CAVALRY VERSUS INFANTRY

According to von Bismark:

- the most difficult part of the cavalry combats is the art of attacking

infantry successfully.....

With the progress of the modern tactic, it becomes every day more difficult to attack it with success. That new infantry tactic consists in the quick formation of masses (squares) and in the destructive effect of a well-kept fire.... When the infantry has its morale intact, a charge... will rarely succeed... here we can recommend:

- (1) to use artillery fire (canister)prior to a cavalry, charge...

(2) to avoid attacking infantry when fresh, well posted and of apparent good morale...

It is much better if the cavalry await the opportunity, to catch the infantry at a disadvantage, during a maneuver or while marching...

When the infantry has received a shock strong enough to to damage its morale, for instance in the steady rain at Dresden and Grossbeeren in August 1813, etc, in these cases, the cavalry has only to present itself to obtain the results.

In the other cases against fresh infantry, one must weight the price of success against the losses that may, occur and balance the success.

Well, the above confirms what we all already know. The success of cavalry against fresh and well trained infantry is almost nil. Occasional square breaking, like at Gamia Hernandez, was pure luck and not the norm. Cavalry charges against poorly trained infantry were much more successful.

We wish to thank George Nafziger for providing us with most of the original French material that was used to prepare our lecture.

Sources

Aubier, Lt.Colonel A. La cavalerie napoleonienne peut-elle encore servir

de modele?, Berger-Levrault, Paris, 1902.

Bonie, General T. La cavalerlie au combat, Baudoin & Cie, Paris 1887.

Bismark, comte von Bismark Tactique de la cavalerie, Levrault, Paris 1821.

Chandler, David The Campaigns of Napoleon MacMillan, N.Y. 1966.

Parquin, Charles Napoleon's Army, London 1969.

de Lee Nigel French Lancers, Amark Publishing Co. London 1967.

Misc. notes and documents from French archives (Archives Guerre).

Back to EEL List of Issues and List of Lochet's Lectures

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Jean Lochet

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com