But the technical difficulties were found to be insurmountable using the technology available in the early 19th Century, and the first tunnel project under the Channel had to be

abandoned. However, the plans to invade England continued and a considerable flotilla was assembled from Dieppe to Belgium as the invasion troops trained around Boulogne.

Sir John Jervis, victor of the naval Battle of St. Vincent and later known as Lord St. Vincent, remarked that he had never said the French would never invade England, but only

that they would not come by sea.

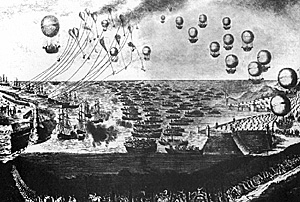

The projected tunnel and the invasion by air may have been abandoned, but that did not stop the popular print trade from presenting to the public a number of fantastic ideas

on ways to transport the invasion troops across the Channel.

Newer Chunnel Projects

Newer Channel projects, most of them also impractical, were developed between 1805 and 1881

until another Frenchman, Thomas de Gamond, took a more scientific approach working with an Englishman, William Low. These two gentlemen thought they had found the solution to

the crucial problem of tunnel ventilation: The trains moving through two parallel tunnels, connected in some places by ducts, should be able to push the polluted air in front of

them, replacing it with fresh air pulled in behind them by suction.

"A couple of thousand armed men might easily come through a tunnel in a train at night," Lord Wolseley, the British army commander, warned, "avoiding all suspicion by being dressed as ordinary passengers." The project was moving very slowly anyway. In two years, only two kilometers of galleries had been dug, and the work was stopped.

Other projects were also dismissed on the grounds of British security. However, political conditions have changed and from London, in 1979, the massive project to build the Chunnel was initiated. The British conservative government of Mrs. Thatcher reached an agreement with

the French socialist government of Mitterand and voila.... Some fifteen years and 13.5 billion dollars later the Chunnel was officially opened by the Queen of England and

President Mitterand.

I have been following with great interest many of the comments that lately have filled newspapers and magazines. Obviously, opinions about the Chunnel are mixed and, understandably, it's not to the liking of some ultra-conservative Englishmen (and certainly some Frenchmen as well). In its May 1994 issue, National Geographic magazine related the comments of a

British retired civil servant:

Well, there are some slim truths in the above statements, but I would not go so far as to not finding any good red wines in England. [3]

But one thing for sure, one does not fool around with a Frenchman's food or wine. When

the bureaucrats in Brussels wanted the French to make their cheeses with pasteurized milk, that proved to be much too much and rightfully the French told them to go to h.... One

has to draw the line somewhere!

Our daughter-in-law, who is from London, had a good laugh at the above comments on French

foods, as she has the time of her life with my wife in the kitchen every time she has the opportunity to visit.

Obviously, the British couple quoted in National Geographic have not read A Year in Provence [4] or Tonjours, Provence by Peter

Mayle. The French have long been used to Englishmen buying weekend homes in Normandy or permanently moving to the sunny French south (Provence being their primary choice).

Last year frontiers virtually

disappeared in the European

Community and Europeans - like it or

not - can live anywhere they want to.

That understandably disturbs some

people.

So, after fighting two world wars side-by-side, and after so much blood spilled in "a common cause," it is time for the French to learn to like Stilton cheese and fish and chips, [5] and for the British to appreciate a good canard a la

orange (duck with an orange sauce) without catchup. We can all follow Voltaire's prescription: "Let us forget one another's follies."

[1] The project is related in Napoleon's Correspondence 14442.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. In 1802, a French engineer presented to Napoleon Bonaparte a project to tunnel under the English Channel. The planned passageway, to be lighted by oil lamps, included a paved road on which coaches would have traveled.

In 1802, a French engineer presented to Napoleon Bonaparte a project to tunnel under the English Channel. The planned passageway, to be lighted by oil lamps, included a paved road on which coaches would have traveled.

In 1808, the scientist Monge L. Hommond [1] proposed to

invade England by means of a hundred balloons of 328 feet (100 meters) in diameter. The car of each balloon was to hold 1,000 men with food for a fortnight, [2] two guns with their wagons, twenty-five horses, and sufficient wood to keep

up the fires for these Montgolfieres or hot-air balloons. This plan, too, proved to be impractical.

In 1808, the scientist Monge L. Hommond [1] proposed to

invade England by means of a hundred balloons of 328 feet (100 meters) in diameter. The car of each balloon was to hold 1,000 men with food for a fortnight, [2] two guns with their wagons, twenty-five horses, and sufficient wood to keep

up the fires for these Montgolfieres or hot-air balloons. This plan, too, proved to be impractical.

Their project was funded and work began in 1881, but stopped two years later after a political campaign publicized the danger of invasion for England.

Their project was funded and work began in 1881, but stopped two years later after a political campaign publicized the danger of invasion for England.

"'I'd rather become the 51st state of the USA than get tied up there," as he nodded toward the steel gray Channel out of the window.... 'Awful place,' added his wife, lifting a teacup

to her lips, 'They drink all the time, and the food is terrible. When I go to the Continent, I take my own bottle of English sauce.'... 'We don't care much for the French,' her husband concluded. 'But the French....' Here a pause, a shudder, as the gull-wing eyebrows shot

upward, 'The French don't care for anybody."

Then the author continues by quoting a French farmer living close to the Chunnel terminal near Calais: "'I went to England once,' he said, 'Never again! All they eat is catchup.' A tiny

explosion of air from pursed lips, then the coup de grace: 'You can't even have a decent glass of red wine!"'

Then the author continues by quoting a French farmer living close to the Chunnel terminal near Calais: "'I went to England once,' he said, 'Never again! All they eat is catchup.' A tiny

explosion of air from pursed lips, then the coup de grace: 'You can't even have a decent glass of red wine!"'

As we noted, times are changing. There is a mixed French-German brigade stationed in

Strasbourg, in the heart of Alsace, a region contested by the French and Germans for decades. Now many Germans from nearby Baden make their homes there, living peacefully with their French

neighbors.

As we noted, times are changing. There is a mixed French-German brigade stationed in

Strasbourg, in the heart of Alsace, a region contested by the French and Germans for decades. Now many Germans from nearby Baden make their homes there, living peacefully with their French

neighbors.

Footnotes

[2] The project does not say anything about wine. A most

regrettable oversight!

[3] England is one of the largest markets for Bordeaux wines and Champagne.

[4] A Year in Provence has been on the "Paperback Best Seller" list of the New York Times for 140 weeks (so far!). It was authored by Peter Mayle originally from London and it describes his sojourn in Provence where he now resides. Highly

recommended. Available from Vintage Press ($10.00).

[5] The French have been quite fond of Scotch whiskey for a number of years.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 8

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com