Dear EE&L Staff,

I was recently reading the article in an old EE&L about the formations that the Guard attacked in towards the end of the Battle of Waterloo. This prompted by having just read Waterloo: New Perspectives by David HamiltonWilliams. In his book he mentions that they probably advanced in Open Square, a la Egyptian Square, the front being two companies wide [division frontage] two companies at the rear and two companies either side in line of threes. A total of eight companies per battalion. I was under the impression that when the Guard was reorganized in 1808, the battalions were reduced from eight companies to four companies per battalion.

I have found the following snippets:

(1) The Imperial Guard had eight companies per battalion as opposed to the six in the Line regiments. (Ref. Waterloo: New Perspectives, David Hamilton- Williams, pg. 340.)

(2) 1806, Grenadiers and Chasseurs two regiments each. Each regiment had two battalions, each of eight companies of 122 men.

1808, Amalgamated to one regiment each. No suggestion of a reduction of the number of companies, except that a battalion may be reduced to two or three companies due to losses. (Ref. Foot Regiments of the Imperial Guard, Michael Head.)

(3) 1805-07, Grenadiers and Chasseurs two regiments each. Each regiment had two battalions each of four companies (200 men per company).

1809, reorganization to one regiment each with no change in composition of the battalions. (Ref. Napoleonic Armies, Ray Johnson.)

(4) 1804, Grenadiers and Chasseurs a regiment each. A regiment had two battalions, each of eight companies.

1806-08, expanded to two regiments. (Ref. Swords Around the Throne, John Elting pp. 185186.)

(5) 1804, Grenadiers and Chasseurs a regiment each. A regiment had two battalions, each of eight companies.

1809, reorganised to one regiment each with four companies per battalion. (Ref. Napoleon's Guard Infantry, P. Haythornthwaite.)

I also believe that the Guard companies were purely "normal," i.e., no voltigeurs or grenadiers as in the Line or Light battalions.

My question: What was the company organization of the Grenadier or Chasseurs battalions of the Imperial Guard?

ANSWERS BY THE EE&L STAFF

From the above snippets, the organization of the Guard Grenadiers and Chasseurs regiments at Waterloo appears to be a confusing issue. However, when reference works are consulted using data traceable to French archives, like that of Philippe Haythornthwaite or Colonel Elting, the issue becomes simple.

The origin of the Guard infantry dated back to the late 1790s when there was formed the Garde des Consuls later to be changed to Imperial Guard on May 18, 1804. Until the reorganization of the Guard in 1806, the Old Guard Grenadier and Chasseur battalions included eight companies.

Then, the decree of April 15, 1806, set forth much of the organization, pay and privileges of the Imperial Guard for the remainder of the Napoleonic Wars. Each regiment was to consist of two battalions, each of four companies of equal status totaling 123 effectives of all ranks. In addition, the decree also called for the raising of two more regiments of Old Guard Infantry, namely the 2nd Grenadiers and 2nd Chasseurs. These regiments also included two battalions each at four companies.

The decree was formal: each battalion included four companies of equal status. Consequently, Guards battalions, grenadiers or chasseurs, were not organized like the Line or Light regiments and did not include the traditional voltigeur or grenadier companies of these units. In the Old Guard grenadiers regiments, all the companies were grenadiers and in the Old Guard chasseurs regiments, all the companies were chasseurs. The same applies to the Middle and Young Guard regiments. (In the Young and Middle Guard regiments, the term grenadier and chasseur was associated with another word such Fusilier-Grenadier, Flankeur grenadiers, etc.)

The Campaign of 1805 and 1806 had shown that the four regiments of Old Guard infantry were organizationally too weak for the rigors of campaign. Consequently, before the Campaign of 1809 against Austria, the second regiment was merged with the first regiment of each arm and the strength of each company increased to 200 effectives (officers and other ranks) on war footing.

In 1811, when the second regiments of Old Guard infantry were raised again, the fourcompany organization was not altered.

One should realize that the grenadiers and chasseurs of the Guard grenadiers and Chasseurs regiments were highly trained veterans capable of acting as skirmishers if necessary, etc. (At Hainaut, two battalions of Guard grenadiers in skirmish order cleared the woods.) Their regular training even included the firing of artillery pieces (which they did at Wagram).

Even after the horrible losses suffered during the retreat om Russia the standards to enter the Guard were kept very high. The candidates Old Guard grenadiers or chasseurs, (as well as those of the Middle Guard) had to have a number of years of service and have served in several campaigns. Whatever his needs, Napoleon recruited his Old Guard regiments with great care.

In 1813, to rebuild his Guard practically destroyed in Russia, he had ordered the 250 combat hardened battalions of line and light infantry serving in the Peninsula each to nominate twelve of their best veterans. Of these twelve veterans from every battalion, half of those nominated had to be distinguished veterans with at least eight years of service, and these soldiers went into the Old Guard. The remaining six handpicked soldiers from each battalion had to have at least four years service and went into the Middle Guard Fusiliers and Chasseurs regiments. (Bowden, Scott, Napoleon's Grande Armee of 1813, Emperor's Press, Chicago, 1990, pp. 28-29.)

To confirm the above, on March 19, 1813, at a time when Napoleon desperately needed soldiers, he wrote: "An officer or NCO may not be admitted into the Old Guard until he had served twelve years and fought in several campaigns; a soldier must have served ten years and fought in several campaigns; but eight years' service is sufficient to enter the 2nd Chasseurs and 2nd Grenadiers. If nominations contrary to this rule are made they shall be presented for confirmation to the Emperor before taking effect." (Lachouque, Cdt,. and Brown, Ann, The Anatomy of Glory, p. 277.)

In 1815, for the Hundred Days Campaign, the situation was a little different but the standards were kept high for the two Old Guard regiments of Grenadiers and Chasseurs. The Emperor ordered the Guard infantry which had accompanied him to Elba to take their place at the head of the Ist Grenadier Regiment. Consequently, the I st Grenadier was the most elite regiment of the Old Guard since a third of its effectives were distinguished veterans of twenty or twenty-five campaigns. In addition, many wore the Legion of Honor.

However, Napoleon, carefully watching the daily returns for the Old Guard regiments, realized that the stringent standards for entry into the Guard set forth in the 1806 decree had to be somewhat relaxed in order to attain the desired manpower. So a new decree dated April 8 was issued. Article 22 of the decree covering the raising of the Guard stated that soldiers to be eligible for the Old Guard should have twelve years service and as many campaigns. However, the minimum height requirements were lowered from 5'10" to 5'5" for the Grenadiers and from 5'8" to 5'3" for the Chasseurs.' In addition, ex-Guardsmen (The recipients of the Legion of Honor, known as Legionaires were exempt from the measurement rule) NCOs and soldiers who had received their discharge were asked to return to the colors. Also, the Line regiments were asked to send two officers and thirty NCOs and soldiers to complete the Guard. The objective of 200 men per company was hard to achieve for the 3rd regiments.

In spite of the overall shortage of qualified veterans, Napoleon decided on May 9 to raise the 4th Regiment of Grenadiers and the 4th Regiment of Chasseurs. These 4th regiments could only raise seven battalions, each regiment fielding two battalions with the exception of the 4th Grenadiers which only had a single battalion. Although the name was not official in 1815, (The title "Middle Guard" had been official nomenclature for some of the infantry and cavalry units. However, in 1815, although used by the army, the "Middle Guard" designation was not officially reinstated) it was customary throughout the army to refer to the 3rd and 4th regiments of Grenadiers and Chasseurs as "Middle Guard" since, although these regiments were also raised from veterans, their quality was not as high as those of the 1st and 2nd regiments. The Middle Guards regiments carried the famous attack of the Guard at Waterloo.

Finally, the last point to answer is about the attack of the Guard at Waterloo. Waterloo: New Perspectives by David Hamilton- Williams tells us that each battalion probably advanced in Open Square, ala Egyptian Square, the front being two companies wide [division frontage] two companies at the rear and two companies either side in line of threes. That explanation cannot be accepted verbatim since the Middle Guard battalions had only four companies.

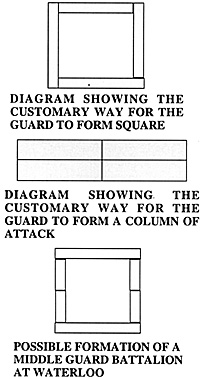

Consequently, if the Guard battalions were in square, the frontage could not have been two companies wide. The only possible explanation is that the Middle Guard battalions formed a column of companies, i.e., a column with a single company frontage, which formed a quick square by breaking number 2 and 3 companies in two and facing them left and right. Then 2 and 3 companies could have been rearranged in columns by 3 or 4. It's probably what took place at Waterloo, if the Middle Guard attacked in squares.' (Besides General Petit's report, there is no other primary source evidence that the Middle Guard at Waterloo attacked in open square.) (We'll probably never know!) So, the battalions could have looked as shown by the diagram on this page.

We hope the above sheds some light on the organization of the Guard and its battle formations.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 7

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com