What follows is mostly the work of Leona; however, her husband provided some of the anecdotal and historical details to tie in her part with the picture Tentation (i.e. temptation) to be found elsewhere in this issue.

What follows is mostly the work of Leona; however, her husband provided some of the anecdotal and historical details to tie in her part with the picture Tentation (i.e. temptation) to be found elsewhere in this issue.

In past issues, Leona's Corner had some Napoleonic recipes which required at least a rudimentary kitchen and a fairly competent cook. There is nothing wrong with that and Leona is busy collecting period recipes (with the help of some of our readers) from the different participants of the Napoleonic Wars. But what about the recipes used by the rank and file? From time to time, space and the interest of the readers permitting, we plan to cover the food habits and related events of the soldiers of the Wars of the Revolution and of the Empire.

Many historians lead us to believe that foraging was exclusive to the French armies of the Revolution and of the Empire. Nothing is further from the truth. For a clear understanding of that point, we recommend the reading of Christopher Duffy's The Military Experience in the Age of Reason, (Duffy thereafter.). During the Seven Years War, Frederick's troops on many occasions had to depend on foraging to survive. The following quotation from Duffy, p. 166, illustrates our point very well:

- "... The hunger of the soldiers recognized no laws, unless a good disciplinarian was in charge of the army, and the passage of the troops resembled that of a swarm of locusts. The demand on firewood was still more destructive. On the march into Bohemia in 1757, detachments went out from the Prussian regiments to dismantle the houses, and 'we carried out shingles, laths, rafters, faggots and finally the equivalent of an entire village into the camp. The unfortunate people raised a chorus of cries, howls, pleas and curses, but we carried on regardless, for we could not live without wood' (Prittwitz, 1935, 105) "

Christopher Duffy continues on page 167:

- "...Marauding in the French army had an almost institutional status, which enabled the French soldier (long before the Revolutionary Wars) to develop a high degree of skill in living off the country. French soldiers could be relied upon to return to the colours as soon as the alarm sounded... "

However, the above is only pertinent to the soldiers on campaign. When peace comes, discipline once more takes control. Then, the Intendance gets its act together and the rank and file receive a regular flow of food.

The next move was to organize the regular camps preferably in the countryside near a city or town. During the period of peace between the end of the Campaign of 1809 and the invasion of Russia in June 1812, the Grand Army was housed in such camps. Davout [1] spread his corps around Rostock. There his soldiers were trained to a high standard under the strictest discipline, went out of the camps only with permission and took care of thieves themselves. The degree of obedience obtained is well illustrated by the comments of the Prince of Mecklenburg, who, upon seeing the geese of the neighboring villages walking in the camp of Rostock, said to Davout's officers: "Here is, Gentlemen, your best praise".

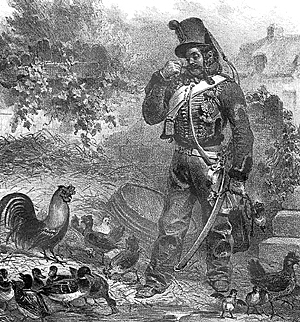

The Hussar, a marechal ferrand (i.e. a farrier) of our picture "Tentation" could very well have been part of Davout's III Corps if not for his shako, which is of a later version. Or perhaps he is thinking about the improvement the ducks and the cock would make in his daily

pot-au-feu, or these ducks bring back memories of his younger years spent at the family farm?

For many years, under the Consulate and the Empire, the daily ration of bread was 28 ounces (about 800 grams) and was reduced in 1810 to 24 ounces (about 700 grams) [2], supplemented by half a pound of meat, 1 ounce of rice or 2oz of dry beans, peas, lentils, etc., a quart of wine [3], some brandy (1/16th of a liter) and vinegar. Fresh vegetables were added whenever available. Wood was also provided for cooking. The system was changed in 1806 and money on the basis of 25 centimes was turned over to the regiment to purchase food, but that is another story to be covered in a future issue.

The common Napoleonic soldier of all nations was accustomed to simple food and living. One of their main worries was to keep their bellies full and to improve l'ordinaire. [4] It could have very well been that what was in the mind of the Hussar in our picture. But soupe and bread with regular ration of wine -- the so-called ordinaire -- kept the French and other soldiers happy, providing there was enough of it.

Usually, the French soldier while in camp had two meals a day. Around noon was the soupe, some boiled meat, beef, mutton or pork, and vegetables. Most of the time, the meat was taken out of the soupe and eaten with mustard and bread. [5]

In the evening perhaps some more soupe, potatoes and vegetables with or without meat. Often, the French soldier ended his meal by soaking his left over bread in red wine. That was called le gateau du soldat (i.e. soldier's cake; by the way, on occasion, my husband still does that.)

As can be seen, boiled meals, i.e. endless versions of pot-aufeu [6], were the most common dishes but stews were also common as the cooking was done by group of 6 to 8 men which had a camp kettle. [7]

In the endless versions of pot-au-jeu (or beef soup), generally the meat was taken out and eaten separately with the vegetables as it will be seen in the recipe below. The remaining broth could be spiked with bread, biscuit, or preferably rice [8] and/or wine.

The Napoleonic wargamer can appreciate the value of the basic pot-au-jeu or beef soup at very little expense and with relatively little work. It is a wonderful winter dinner, and last week we had the pleasure to share a pot au-jeu with some friends. They loved the soup made with the broth and.spiked to their (surprised) delight with white wine. They were surprised that the tradition went way back to the Napoleonic times and even before! The boiled beef was a separate dish as recommended below.

In the future, Leona will present some variations of the potau-feu, used by other nations.

Pot-au-feu is a very old family dish that goes way back in time, and is prepared in an earthenware, cast iron or modem kettle. This preparation provides two dishes; the delicious soup, to which can be added a variety of garnish suitable for clear soups like bread, toasted bread, rice, a variety of pasta, etc., and meat and vegetables. These two dishes, simple as they are, are always appreciated especially in winter. Gherkins, Samphire pickled in vinegar, mustard, horseradish or horseradish sauce can be served with the meat.

The classical version of pot-au-jeu is made with beef. However, in certain provinces of France, it is customary to add chicken, veal, pork and mutton. On occasion, chicken is replaced with duck (it may be what the hussar of our picture is thinking about).

Whatever meat is used in this dish, the method is the same. The following is the method Leona likes best. It will serve at least 4 or more people and always makes a great hit with guests.

Ingredients

A kettle large enough to hold all the ingredients. beef (cooking time 3 hours) 4-lbs of shank(*), marrow bones 6 ounces,

Vegetable garnish (cooking time 1 1/2 hours), carrots, onions, turnips, leeks (2 of each vegetable per person), 1 large head of curly cabbage

4 potatoes (1 per person), a large herb bouquet consisting of 6 parsley sprigs, 1 bay leaf, 2 garlic cloves, 4 peppercorns tied in cheesecloth.

1 small horseradish (optional) salt and pepper to taste

Preparation

(1) All the meat and vegetables listed above are simmered together but are added at various times into the kettle, depending on how long they take to cook. Start the cooking 3 hours before you expect to serve to be sure the meat is well cooked.

(2) Prepare the vegetables: peel the carrots and turnips (do not cut them, leave them in one piece; peel the onions, trim and wash the leeks. Wash and cut the cabbage in two. Clean and peel horseradish.

(3) Place the beef in the kettle with the vegetables, (except the potatoes and carrots which should be added 45 minutes before the end of the cooking cycle), herb bouquet and marrow bones. Cover with water at least 6 inches above the meat and vegetables (more liquid may be added later if necessary).

(4) Set kettle over moderate heat, bring to a simmer and skim. Partially cover the kettle and simmer slowly for 3 hours.

(5) 45 minutes before the end of cooking do not forget to add the carrots and potatoes.

(6) After the 3 hours of cooking, part of the broth is separated from the meat and vegetables and used to prepare the beef soup which is served before the meat and vegetables.

(7) The beef soup is prepared prior the removal of the meat and vegetables and prepared as it follows:

2. For special taste add some white or red wine to the soup. (8) Remove the meat and vegetables from the rest of the broth (the excess can be kept for more soup) and place on a large platter. Keep warm and serve after the beef soup. The meat is usually served with gherkins, samphire pickled in vinegar, mustard, horseradish or horseradish sauce according to your taste etc..

[1] There were many instances in which the Napoleonic soldiers under the command of a disciplinarian behaved well. Davout was such a strict disciplinarian. Like many other generals, in time of peace when supplies were sufficient, he did not allow foraging. In time of war, he never accepted marauding by individuals. Only when on campaign and supplies were short, was foraging by small parties of 8 to 12 men tolerated and the inhabitants properly compensated. A receipt was to be issued to the inhabitants. Of course, many foragers did not bother with such formalities. Marauders and pillagers, if caught, were shot.

A RECIPE FOR POT-AU-FEU OR BEEF SOUP

* substitutes for beef shank are: rump pot roast, bottom round chuck pot roast, brisket (or for the Napoleonic soldier: horse meat!)

1. Remove enough broth, then boil the broth and add to your taste, rice, small pasta or both. Simmer until the pasta and/or rice is cooked.

Endnotes

[2] The basic food for the soldier (and most peasants of the time) was bread. When bread was the only available food, the normal ration was considered around 2 pounds (about a kilogram) and remained around that level in many armies. That was the quantity of bread supplied to Frederick's soldiers during the Age of Reason (see Christopher Duffy's The Military Experience in the Age of Reason, Atheneum, New York, 1988, p. 161). In 1793, during the invasion of France, prior to Valmy, the Prussian army stopped every 6 days to bake a 6-day supply of bread. On many occasions, such as during the Campaign of 1813 in Germany, the military intendance was unable to supply even that reduced quantity. Deprived of their most basic needs, Napoleon's young soldiers were on the verge of starvation during the armistice of the summer of 1813.

[3] No wine, no soldier or Pas de vin, pas de soldats is an old adage in the French army. The preferred kind was a dry red wine.

[4] In the French army, amiliorer l'ordinaire, (i.e. improve the food as l'ordinaire is the proper terminology for the food provided by the Intendance) has always been a high priority.

[5] The bread was given once a day and the soldier could nibble en his ration whenever he was hungry.

[6] Replace the beef with chicken and you have the poule-au-pot, or Pot-au-Jeu a la Bearnaise that goes back to Henry the IVth (1600) (who was from Bearn, a province from the south of France); replace the beef with ham and you have a Potee Morvandelle, or with just cabbage and beef you have something close to the Irish boiled diner.

[7] Camp kettles were often lost while in campaign and often replaced from enemy stores. In 1807, during the terrible Campaign of Poland, the captured Prussian magazines of Berlin, Potsdam and Spandau furnished no less than some 49,000 camp kettles and 47,000 stew pans for the Grand Army.

[8] Rice was highly valued as a healthy food that prevented dysentery and in addition, it gave body to the soup.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 6

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com