One of the persistent Bonapartist myths that keeps on turning up, year in and year out, is the idea that Napoleon solved the great tactical debates of the 1780s between the Column and the Line, by inventing the hybrid (or compromise) formation of the Ordre Mixte.

I believe that this myth was originally started by Napoleon himself, taking his cue from some of the tactical orders he issued in Italy in 1796 (eg crossing the Tagliamento). He again prescribed the Ordre Mixte in some of his great battles as Emperor (eg Soult's attack on the Pratzen at Austerlitz, Ney's operations at Friedland, d'Erlon's at Waterloo&c), and he can be found boasting about it several times over in his St Helena memoirs. Since that time it has been seized upon by his admirers as the 'perfect' infantry assault formation, and yet more proof that the Emperor was indeed a genius in absolutely every branch of the military art. The fact that he was actually mainly a gunner and a strategist, with no true understanding of the details of infantry work, mattered as little to these uncritical apologists as it did to that other, equally wild-eyed, group of apologists who have identified Napoleon as the leading literary figure (ie 'The greatest user of the French language', no less) of his generation...

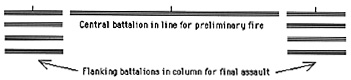

The theory is that whereas the line was good for fire but poor for shock charges, and the column was vice versa, the Ordre Mixte combined the best features of both. The attacking demi-brigade or regiment would first present a firing line of one and a half battalions, to wear down the enemy by musketry. Then the two flanking battalions would charge forward in column with the bayonet. Since the whole operation would take place on the frontage of only one and a half battalions, the initial firefight would be fought on equal terms but the subsequent two-battalion assault would enjoy the benefit of superior numbers.

So: Voila!

So: Voila!

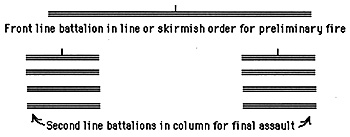

The main problem with all this is that it was often psychologically very difficult for troops in line to engage in a prolonged firefight and then cease fire, on demand, to make an assault. It was far easier for them to continue firing without advancing, or alternatively to hang back behind the front line without firing (until the enemy had been suitably weakened) and only then to get involved in the battle, and charge forward at the critical moment. Thus it made psychological sense to use the front line (whether in close or open formation) only for fire, and the second line only for shock:

It really does not make any sense to use the forward elements of an assault column for prolonged firing before the attack is unleashed, since this will tend to exhaust them and thereby also remove the aggressive impetus from the whole column. Troops who are held in the rearward ranks of a column will tend to take their cue from the men they can see ahead of them in the same column, nearer to the enemy. This seems to have happened in Soult's Ordre Mixte at Albuera in 1811, which opened fire and could not be persuaded to stop, even though it greatly outnumbered the opposition. The result was the longest and most bloody exchange of musketry in the whole of the Peninsular War, eventually leading to a French defeat.

It really does not make any sense to use the forward elements of an assault column for prolonged firing before the attack is unleashed, since this will tend to exhaust them and thereby also remove the aggressive impetus from the whole column. Troops who are held in the rearward ranks of a column will tend to take their cue from the men they can see ahead of them in the same column, nearer to the enemy. This seems to have happened in Soult's Ordre Mixte at Albuera in 1811, which opened fire and could not be persuaded to stop, even though it greatly outnumbered the opposition. The result was the longest and most bloody exchange of musketry in the whole of the Peninsular War, eventually leading to a French defeat.

It seems to be far better to detach different, specialist troops ahead of an assault column, to deliver the initial softening fire against the enemy and thereby to spare the column itself from the searing heat of battle. Then, when the time is ripe to commit the column into its assault, the troops who form part of it will be relatively fresh and ready for their task.

This perspective is reinforced by the finding that the Ordre Mixte was actually used by Napoleon's army on remarkably few occasions - and mainly when the Emperor in person was watching. Even then, as in Soult's case on the Pratzen or Ney's at Friedland, it seems that the formation employed on the ground often bore relatively little relationship to the classic Ordre Mixte that the great Napoleon is supposed to have prescribed. It is certainly my own belief that the classic Ordre Mixte was used in a major battle on very few occasions indeed. Very much more frequent were attacks in column, line or skirmish order or - perhaps most frequent of all - attacks that were first prepared by a dedicated skirmish line and then delivered by a body of formed troops who had not previously been exposed in the front line at all. Such attacks have sometimes been reported as examples of the Ordre Mixte, but in fact they were not. Equally a line which happens to have its flank secured against cavalry by a square or column should not be seen as a true Ordre Mixte, but rather as a local defensive expedient intended to improve the firepower potential of the line, without any offensive purpose. The true Ordre Mixte should be seen as an ingenious experiment that led nowhere: a whim of the Emperor's that would never have been widely discussed if Napoleon had not happened to be such a commanding figure. I maintain that it was not really a robust or viable tactical formation, and its invention by Napoleon added nothing to his reputation.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 5

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com