Note from Editor: The Battle on the River Piave took place on May 8, 1809. The following account of the battle is authored by a long time Italian reader and contributor of EE&L and is based on General Eugenio Barbarich's La Piave in due guerre di liberazione italica (1809-1918), Rome, 1923. Mr. Gioannini authored Neither Caesar Nor Punchinell, The Army of the Kingdom of Italy in the 1812 Campaign in Russia, published in EE&L 5 and 6.

The French therefore had to act by using the element of surprise and engage the enemy before they reached Conegliano and the Livenza River, attacking on a limited front and establishing a bridgehead beyond the Piave.

Fords or, according to the level and speed of the river, temporary pontoon bridges appeared to be more suitable to the purpose than bridges or other permanent gangways, whose function of delaying the enemy's advance the French had experienced to their advantage in the early phase of the campaign. Toward the bridges and, particularly, toward Nervesa and the Priula bridge feint actions might, however, be advisable.

This was really a daring plan which was called for by the urgency of the moment, the morale of the enemy, the course of the main campaign on the Danube as well as the Viceroy's desire to redeem himself, by a stroke of luck, from the errors committed during the first phase of the campaign in Veneto. [2]

Orders

All these purposes were evident in the orders issued by Eugene from his headquarters at S. Artien on the morning of May 7th, as reported in this letter to Napoleon:

"Yesterday, the army arrived on the Piave, with Treviso on its right. The rest of the Austrian army had crossed over, during the night, on the two bridges they had build at Vidor and Nervesa. These bridges were either either removed or sunk: 4 sections of the bridge on the Priula have been competely burnt....

Tomorrow, then, I am going to make a false attack on the bridges at Nervesa and of the Pirula and made all the army cross over in 2 columns around Lovadina, the cavalry shall transport the vanguard and the rest crossing over on a small bridge of rafts, which will be built during the night, the caissons crossing later on a temporary bridge and a Division shall move by Covolo, to turn the enmey's right." [3]

The destinations of this movement were Conegliano and Sacile, that is, the Austrian back-lines stretching toward the Livenza River.

For their part, the Austrians needed a rear guard battle on the Piave River to keep the enemy at bay in order to gain time for their slow supply train to advance along the road from Conegliano to Sacile and Pordenone. This would imply taking up a position near the river's left bank, thus keeping their forces concentrated in a central position and ready for a counterattack. This was in theory. In practice, remembering what had happened at the crossings of Vidor, Nervesa, the Priula bridge and Ponte di Piave, the Austrians detached part of their forces to these places in order to avoid any surprises. Masses of troops were therefore posted in front of Nervesa between Susegana and Colfosco, at Barco and at the Priula bridge, to the great imperilment of the whole army, whose bulk should have been deployed in a central position in front of the fords and the gangways at Lovadina, from where it could have effectively defended the access ways to Conegliano, via Bocca di Strada and S. Lucia di Piave.

Danger

The danger for the Austrian forces scattered along the river increased further as other troops were sent off as flanking detachments. Erzherzog Johann established his observation point in the castle of S. Salvatore di Collalto.

The rain that had fallen on the 6th as well as the sudden changes in the level and the speed of the current made the Austrian Staff believe that the passive obstacle of the Piave River would allow them to recuperate the four days they had lost in April, from the 19th to the 22nd while pursuing the French toward Treviso and Vicenza.

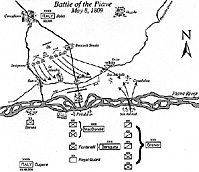

A thick fog covered the Piave valley as General Dessaix, Ospedaletto's brave defender, led the French advance guard to the fords of Lovadina just before 5 a.m. on May 8th. Elite troops, 300 voltigeurs and 50 chasseurs under the command of Captain Traverse, marched at the front. They crossed the rough and high current of the Piave River and at about 5:30 a.m. received other voltigeurs and the 9th Chasseurs as reinforcements. After consolidating the small bridgehead on the left bank, Dessaix sent a squadron of the 9th Chasseurs in reconnaissance toward Case Campana. Suddenly the French horsemen fell under heavy artillery fire and were attacked, repulsed and pursued by an overwhelming Austrian cavalry.

What the chasseurs had come across was the Austrian main battle line that formed an arc in front of the crossing points of the Grave di Papadopoli - from Cimadolmo to Tezze, from Borgo Malanotte to Case Campana and the Priula bridge. In the meantime the water level kept on rising, making things worse for Dessaix (...)

The Fog Lifts

Large Map 1: 8 A.M. (slow: 87K)

At about 7 a.m. the fog lifted. Finally getting a clear view of the battlefield, the Archduke realized that the movements toward Nervesa and the Priula bridge were but diversions and the real threat was instead at the Grave di Papadopoli. Consequently he ordered General Wolfskehl to place himself at the head of the dragoon regiments Savoia and Hohenlohe, presently in position at the Case Campana, and drive the French advance guard back to the fords of Lovadina; in the meantime a column of light troops :(6 battalions, 2 hussar squadrons) under General Kalnassy would advance on Tezze, S. Michele and Cimadolmo to cover the roads to Oderzo and the Livenza River.

With some artillery support, General Wolfskehl led his squadrons at full gallop against Dessaix's hastily formed squares and forced them to withdraw back to the fords. It was about 8:00 a.m.. Three infantry brigades (Marziani's, Gavassini's and Kleinmayer's), with four hussar squadrons on their flanks, advanced to support Wolfkehl from Bocca di Strada to Case Campana and took up positions along the Piavesella stream. The latter were led by Erzherzog Johann in person, who wanted to be present at what he thought would be a favorable outcome of the engagement. From Case Campana the Archduke issued a new battle plan. He sent the following orders: to General Albert Gyulai (VIII Corps) to detach the Colloredo brigade with four squadrons toward Barco as a threat to the enemy's left flank; to the troops in front of Lovadina to be ready to press again the French, this time with the support of 20 guns; to some hussar squadrons (Regiment Ott) to move beyond Borgo Malanotte and thus keep the link with General Kalnassy's detachment in Cimadolmo.

Before 9 a.m. the Austrian counterattack was in full swing: Dessaix's repulsed advance guard thronged in disorder on the fords of Lovadina. The crisis is well described by General Broussier who was at that moment crossing the Piave at Lovadina:

"At the moment I reached the left of the Piave, the enemy after repulsing the charge of the 9th Chasseurs … Cheval, a few runaways came up to cross over the river, it was rather difficult to rally a part of them and to make them move forward again." [4]

Broussier's division, with the 9th and 84th regiments of the Line (Ospedaletto's veterans), had marched onto the field at about 8 a.m.. Their action appeared rapidly bound for success, as soon as a well timed flanking diversion beyond the Grave di Papadopoli distracted the Austrians, constantly worried about their communication lines to Oderzo and the Livenza River. For this purpose, as early as 7 a.m. General Sahuc had sent a party of Chasseurs … cheval from Salettuol across the Grave di Papadopoli to Cimadolmo and Tezze. The presence of French cavalry attracted General Kalnassy's attention immediately. But Sahuc's chasseurs were soon joined by Grouchy's and Pully's squadrons, and all together formed an offensive flank that could support Dessaix and Broussier's recovering action as well as threaten Kalnassy's advance.

Crossing with Difficulty

By that time General Broussier's troops, under the personal supervision of the Viceroy, were slowly crossing the river at Lovadina with increasing difficulties due to the water level as well as the speed of the current. The infantry had to wade in water up to their shoulders. Ropes were stretched between the two banks and expert swimmers sent to keep them taut. Nonetheless, many soldiers were swept away by the surging current. The cartridge boxes were tied on to the muskets, which were carried above their heads. As the building of a pontoon bridge proceeded with exasperating slowliness and many difficulties, Lamarque's division, following Broussier's, crossed the river in march column so as to cut their way through the water more easily.

The Austrians, faced with two attacks at Lovadina and Cimadolmo, hesitated and missed their chance of victory as the time slipped away from them. In fact, what both parties needed was an action which could gain space in front so that its own infantry could maneuver. Who first succeeded in getting this would lay a serious claim to victory. The cavalry was the most suitable arm for this goal and about 21 squadrons on each side were presently facing each other on the plain beyond the Grave di Papadopoli.

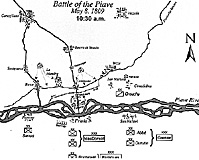

Both commanders had the same thought at the same moment. At about 10a.m. the Archduke sent one of his staff officers to General Wolfskehl with orders to attack once again. At about the same time Colonel Triaire, one of Eugene's ADCs, brought an attack order to the French cavalry.

At the head of the latter was the dragoon brigade under General Poinsot, who took command of the 28th regiment. General Pully, the division commander, was at the head of the 29th regiment. [5] Their forward movement was suddenly stopped by a large dike: the Austrian soldiers behind this obstacle sneered loudly at the badly positioned French horsemen. Although under the canister fire of 20 guns, nonetheless the dragoons succeeded in crossing the dike and fell upon the astonished enemy sabering the gunners. On the Austrian side, Colonel Callot was mortally wounded, General Reisner was taken prisoner and 14 pieces were lost. [6]

Charged

Large Map 2: 10:30 A.M. (slow: 76K)

Soon afterwards the French dragoons charged the Austrian cavalry deployed en bataille not far from the dike. As there was not enough space for the Austrian masses to maneuver, the two French dragoon regiments, charging in small squads (open order), rapidly got the better of the massive enemy formation. While General Poinsot with the 28th charged the Savoia Dragoons, General Pully with the 29th engaged the Hohenlohe Dragoons in a fierce melee. As the French stormed the village of Le Mandre, the Austrian Dragoon division was routed. General Wolfskehl was mortally wounded in the melee and many other cavalry officers were killed or taken prisoner.

Carried by their elan, the French dragoons pushed on to the outskirts of Conegliano, where they ran into the Austrian supply train and put it in the greatest of disorder. At this point they were recalled back to the battlefield. In the meantime Sahuc's squadrons had vigorously charged and defeated the Austrian defenders of Barco, in front of the Priula bridge.

At this juncture the French needed to reap the benefits of the dragoons' efforts which meant settling the situation at the fords where the water level was still rising, retaking the initiative at Le Mandre and acting on the wings. An excellent opportunity for the latter arose beyond the Grave di Papadopoli at about noon.

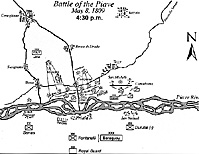

Several hitches had made a coordinate managing of the battle impossible for the Viceroy. Consequently, the Archduke could reasonably hope to succeed in disengaging his troops and withdraw to the Livenza. But at about 4 p.m. the fighting broke out again as fierce as ever. Prince Eugene, encouraged by the progress of Dessaix at Le Mandre, decided to deliver the final blow with the troops at hand (34 l/2 battalions, 8 elite battalions, 58 guns and the cavalry).

Large Map 3, 4:30 P.M. (slow: 67K)

He therefore ordered General Grenier to move against the Austrian left wing at Cimadolmo and, with the support of Grouchy, to outflank it; General MacDonald, with the support of Sahuc's and Pully's cavalry divisions, to reopen the hostilities in the centre so as to sustain Grenier in his outflanking movement. Finally, the Viceroy sent orders to Dessaix's advance guard to attack Le Mandre once again.

Rally

Upon receiving these new orders the French troops rallied and resumed their advance between 5 and 6 p.m.. They forced the Austrians to give up Borgo Malanotte and Case Campana, and Gifflenga's Italians stormed Cimadolmo with fixed bayonets (?). Lamarque's division advanced on the Piavesella to threaten the Campana mill; General Dessaix pressed the enemy along the road from Le Mandre to Susegana and pushed on to San Salvatore di Collalto.

At 8 p.m. the Austrians were everywhere in full and disordered retreat to Conegliano, pressed upon by the French who, as darkness fell, rallied and encamped along the Piavesella. On the 9th the rest of Eugene's army crossed the Piave River and began the pursuit. On the Austrian side losses were heavy: 400 dead, 697 wounded, 1,681 prisoners, 1,120 stragglers. All in all 3,896 were hors de combat. Fifteen guns were also lost, together with other war materials. As 18,000 infantry and 2,800 cavalry had taken part in the battle, the losses amounted to 19%. On the French side the date is unreliable, but total losses (dead, wounded and stragglers) were reported to be about 2,000. As 42 l/2 battalions were supposed to be on the field (34 1/2 of the line, 8 elite, about 650 men each), the French strength at the battle of the Piave River was about 26,000 infantry and 4,500 cavalry. It follows that French losses were 6%, a ratio of 1 Frenchman to 3 Austrians.

[1] Rusca's Division had in fact, been entrusted with a flanking mission, but on the strategical level. They left Trento on May 4th, advanced across the Val Sugana on the 5th, reached Primolano on the 6th and Cordevole on the 7th and made for Belluno on the 8th (Revue d'Histoire Militaire, 1900, P.794)

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Upon arriving in proximity to the Piave River the French had to face the following problems: crossing the river at any cost in order to set out in pursuit of the Austrians across the Veneto; maneuvering in such way as to force the main body of the enemy forces to fight and cut it off from its lines of communication. Since on the grand tactical level the French had missed the opportunity of sending flanking columns across the hills or along the coast [1] both objectives could be gained only by means of frontal actions.

Upon arriving in proximity to the Piave River the French had to face the following problems: crossing the river at any cost in order to set out in pursuit of the Austrians across the Veneto; maneuvering in such way as to force the main body of the enemy forces to fight and cut it off from its lines of communication. Since on the grand tactical level the French had missed the opportunity of sending flanking columns across the hills or along the coast [1] both objectives could be gained only by means of frontal actions.

Jumbo Map 1: 8 A.M. (slow: 215K)

Jumbo Map 2: 10:30 A.M. (slow: 261K)

Preceded by the Italian dragoons Napoleone under the command of Colonel Gifflenga and covered by Grouchy's dragoon division, Abbe's infantry division had crossed the Piave at the fords of San Michele. This village (at right) as well as Cimadolmo were rapidly seized so that the way to Oderzo and the Livenza was now open to the French. The current prevented Durutte's division from crossing the Piave at Lovadina between 2 and 4 p.m.. They moved downstream to the fords of S. Michele, but again the current was so strong that Durutte's troops had to put off their crossing to the following day.

Preceded by the Italian dragoons Napoleone under the command of Colonel Gifflenga and covered by Grouchy's dragoon division, Abbe's infantry division had crossed the Piave at the fords of San Michele. This village (at right) as well as Cimadolmo were rapidly seized so that the way to Oderzo and the Livenza was now open to the French. The current prevented Durutte's division from crossing the Piave at Lovadina between 2 and 4 p.m.. They moved downstream to the fords of S. Michele, but again the current was so strong that Durutte's troops had to put off their crossing to the following day.

Jumbo Map 3: 4:30 P.M. (slow: 226K)

Epstein, Robert. Prince Eugene at War, 1809, The Emperor Headquarters, Chicago, 1984.

OTHER SOURCES:

OTHER SOURCES:Footnotes:

[2] From a letter of Caffarelli to Duroc: "S.A.I. m'a paru vivement affectee du mecontenment de l'Empereur. Cela l'occupe beaucoup et le Prince en souffre." which translate as: " His Imperial Highness, appears to me greatly affected by the Emperor's discontentment. That preoccupies him a great deal and he suffers a lot".) (du Case, vol. XIII, p. 176)

[3] French text: "Hier l'armee est venue sur la Piave, en laissant Treviso a droite. Le reste de l'armee autrichienne avait passe, pendant la nuit, sur les deux ponts qu'ils avaient etablis … Vidor et … Nervesa. Les ponts ont ete retires ou coules: 4 arches du pont de la Priula ont ete brulees totalement... Demain, alors, je ferai une fausse attaque sur les ponts de Nervesa et de la Pirula et je ferai passer en deux colonnes, savoir: toute l'armee … hauteur de Lovadina, la cavalerie portant l'avangarde et le reste passant sur un petit pont de radeaux, qui serait fait cette nuit, les caissons passant ensuite sur un pont volant et une division passera … Covolo, pour tourner la droite de l'ennemi". "Historique de la Campage 1809. Revue d'Histoire Militaire>, 1900, p. 796. The flanking maneuver toward Covolo never took place.

[4] French text:"Au moment o— je touchais la rive gauche du Piave, l'ennemi ayant repousse la charge du 9me Regiment de chasseurs … cheval, quelques fuyards se presenterent pour repasser la riviere, il me fut assez difficile d'en rallier une certaine partie et de la faire marcher en avant". Journal historique de la Division Broussier, p. 34.

[5] The 2nd Dragoon division was commanded by General Pully and was constituted of a brigade of three regiments (23, 28th, 29th) led by General Poinsot.

[6] Colonel Callot was the IX Corps Artillery Commander, General Reisner the Army Artillery Commander

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 13

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Emperor's Headquarters

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com