Note from Editor: We present this article as a two-part complement to the attack of the Middle Guard at Waterloo as per General Petit's report to be found elsewhere in this issue. Part I is authored by George Nafziger and Part II by J. Lochet follows with complementary data and comments.

PART I: ON NAPOLEONIC SQUARES by G.F.Nafziger

The square was the universal anti-cavalry formation. Each nation formed it according to the requirements of its battalion organization.

The square was the universal anti-cavalry formation. Each nation formed it according to the requirements of its battalion organization.

The French Reglement de 1791 set the formation of the square with three ranks on each face. When forming square it was done by divisions and a column was formed at the distance de peloton, or length of a peloton formed in line. The first division did not move, the last division did an about face and the center pelotons swung out to the right or left to form those faces of the square.

The tactical history of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is filled with a multitude of comments about infantry forming squares. It's use is very straight forward and there is really very little question about its use. There are, however, a few minor questions that need to be answered.

Maneuverability

The first question is the maneuverability and speed at which a square could be marched.

In his description of an attack at Geisberg, Girardon

[1] states that the Chaumont Battalion moved onto a open plain in column by peloton, until it was just below Geisberg. At that time it formed itself into square, because the terrain was open and the threat of cavalry significant. It was jointed by the 2/33rd Line Regiment, which also formed in square on the left of the Chaumont Battalion. Together the two battalions "charged" the enemy with bayonets, deployed the battalions (into line) and moved across the plateau at the "pas de charge" and striking two Austrian battalions. The French continued the pursuit, probably in line as no reference was made to any formation change until they arrived before the Geisberg Chƒteau, where they reformed their line. This means that the charge was probably made in square not column or line.

Also, if this maneuver could be made by a revolutionary battalion, there is no reason why it could not have been done by any regular, line infantry formation during the entire period. The probability of it's being done very frequently, however, is open to discussion.

The battle of Lutzen in 1813 provides a good example of several uses of the square. It should be remembered that the French were, in the spring of 1813, desperately short of cavalry and were under constant threat by allied cavalry.

As Marmont advanced onto the battlefield towards Pergau he acted in accordance with Napoleon's instructions. He advanced his forces in nine columns on several lines, ready to form square instantly and advancing in echelon. The 20th Division crossed Starsiedel at the "pas accelere" [2] with Bonnet's 21st Division en echelon to the left and Friederich's 22nd Division in the rear.

Marmont's corps was attacked by Prussian cavalry, which surprised his forces. The 37th Legere Regiment, formed square, but broke and fled in terror. The 1st Marine Artillery Regiment, outfitted as an infantry regiment, formed in squares to the east of Starsiedel, when it was charged by the Brandenburg Cuirassier Regiment. Though the Brandenburgers had caused the 37th Legere Regiment to break, the 1st Marines repelled them easily. No doubt the surprise of the attack had worn off and the 1st Marines had the time to set their square.

Marmont withdrew Compan's 20th Division to the edge of Starsiedel and formed his forces into several squares, so that any new attack would not throw them into the same disorder that had struck the 37th Legere Regiment. These squares were placed so close that they could not fire unless the enemy cavalry actually passed between them.

Difficult Terrain

Also at Lutzen we have an instance of how difficult terrain was handled by units marching in square. Around 3:00 p.m., the IV Corps was advancing slowly towards Pobles and the crossing of the Grunabach. Facing it was Wintzingerode, who occupied the east bank of the Grunabach stream. Though faced with enemy artillery, the French were advancing in square because of the cavalry threat. Under the cover of the French guns, Morand's 12th Division broke into columns, crossed the stream, and reformed itself into squares to resume its advance.

There is an instance of an Confederation of the Rhine formation using squares with the IV Corps which is also enlightening and should be considered when reviewing the use of squares.

Two Hessian regiments were moving against Klein-Gorschen. The Hessian Leib-Garde Regiment formed into square and advanced against Klein-Gorschen. The Leib Regiment moved in the second line to the left and the Fusiliers moved on the extreme left, formed in column and covering the whole advance. The force was covered by a screen of Hessian skirmishers and a redoubled artillery fire in support. The attack advanced at the "sturmschritte" (storming pace)" to seize the bridge to Klein-Gorschen. Here, we have infantry both attacking and advancing at the "sturmschritte", which was the Hessian equivalent of the "pas de charge!" The square was obviously not slower than any other formation, despite modern thought on that point.

Large Illustration (slow: 33K)

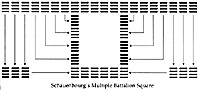

However, the intended use of these squares is not clear. Schauenbourg's notes do not indicate if this formation was intended as a defense against cavalry or if they were intended for other, unnamed purposes.

In one example of a massive square formed by battalions in lieu of companies, the line folded back into a square with each battalion marching backwards to the required depth, performing a perpendicular turn towards the center and marching to its final resting place. The front of the square was formed by battalions that retained their initial position. The rear was formed by the flank battalions marching directly to the rear, halting at the prescribed distance, turning inwards and marching in a line to their final position. This is very much like the ploying of a line into an attack column.

Sweeping Movements

In a second maneuver Schauenbourg used a system of folding the line on the center much like the Prussians used to form square from line under the directions of the 1788 regulation. The line folded on the center battalions, much as in the previous example. However, the French battalions marched independently of one another, in great sweeping movements towards their final position.

This type of maneuver may seem very theoretical until one realizes that it is essentially the formation that Macdonald employed at the battle of Wagram. There are also other examples of this type of formation being used, though Macdonald's is the most famous.

The French infantry also formed regimental squares. These were large and more complex affairs that provided a maximization of fire while retaining the integrity of the square formation. These squares formations were used at Lutzen, Borodino and Weissenfels. However, these formations were not made in immediate response to an attack by cavalry, but were, at least for Lutzen and Weissenfels, the formations in which the French marched onto the battlefield.

One of the many current misconceptions of the square is that it was a fixed formation, barely able to move. This is not true. When the Prussians retreated off the field after their defeat at Jena-Auerstadt, their rear was a Saxon grenadier battalion in square. It outmarched the pursuing French infantry and held the French cavalry at bay.

In the battle of Jena, Baron Seruzier, commander of the artillery of General Morand's Division of the III Corps (Davout), states in his memoirs: "J'en etais la quand notre division, formee en carres d'infanterie marchant au pas de charge, parvint a notre hauteur." (which translate as: "I was there, when our Division, formed in infantry squares moving at the pas de charge, aligned itself with us, JAL). That passage states very clearly that he witnessed a French division formed in square, marching at the pas de charge (120 paces per minute), up a rise. Such a passage is rare because it specifies the march rate and the formation, but it clearly shows that the square was as mobile as any other formation.

One reason that a square might have gained the reputation of moving at a slower rate would be if the infantry forming it was poorly trained and could not maintain formation at the higher rate of speed. It is also possible that it moved in a loose square that tightened up and set itself when cavalry approached. If cavalry was too near the infantry square might well not move very quickly so as to prevent its ranks from opening up due to the accordion effect. It would be possible, under those circumstances, for a formed square to be broken if cavalry could dash in upon it quickly enough before it closed all the gaps.

[1] (Commandant) Girardon, was the commanding officer of the Battalion de R‚quisition de Chaumont, one of the volunteer units of the first ban (JAL).

Colin, J., La Tactique et la Discipline dans les Armees de la Revolution; Paris, Librairie, Militaire R. Chapelot et Cie.

More Squares

Related:

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. In another discussion, Colin presents column tactics which Schauenbourg trained his division to use. At least twice in major exercises, Schauenbourg had his division convert from a line of battalions into a massive, four sided square. These formations bear very strong similarities to Macdonald's Wagram column as well.

In another discussion, Colin presents column tactics which Schauenbourg trained his division to use. At least twice in major exercises, Schauenbourg had his division convert from a line of battalions into a massive, four sided square. These formations bear very strong similarities to Macdonald's Wagram column as well.

In 1813, due to the lack of cavalry to protect it, many units of the French army marched onto the battlefield at Lutzen in square. How slow could the square have truly been if it was used on a divisional scale by maneuvering armies? Obviously, the historical record shows that the formation had no impact on the speed with which a battalion could maneuver.

In 1813, due to the lack of cavalry to protect it, many units of the French army marched onto the battlefield at Lutzen in square. How slow could the square have truly been if it was used on a divisional scale by maneuvering armies? Obviously, the historical record shows that the formation had no impact on the speed with which a battalion could maneuver.

Footnotes

[2] The pas accelere is a marching pace of 100 paces per minute.

Sources

Nafziger, G.F., Lutzen and Bautzen, 1992, Chicago, IL, Emperor's Press.

Nafziger, G.F., A Guide to Napoleonic Warfare, 1995, Cincinnati, OH, Privately Published.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 13

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Emperor's Headquarters

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com