The Kingdom of Italy was the first of France's satellite states and one of the greatest contributors of troops to the Napoleonic armies. Between 1802 and 1814, upwards of 200,000 Italians served in the kingdom's army, in virtually every region of Europe and all of Napoleon's campaigns. The army was a substantial force within the Imperial armies, mustering some 80-90,000 soldiers at its height in 1812.

The military system and establishment of the kingdom mirrored that of France, and its leadership was drawn from the most loyal of Italian officers. What places the Italian army in a peculiar light is the fact that prior to the French Revolution and Empire, there was no "Italian state", but a series of small disunified duchies. The creation of an Italian state in northern Italy and the establishment of an "Italian army" was truly a revolutionary event in Italy and a major credit to Napoleon's political and administrative ability.

GENERAL HISTORY:

The first Italian military formations were organized shortly after General Bonaparte's Armee d'Italie swept through northern Italy in 1796. They were composed of several thousand Italian revolutionaries, many with no prior military service. The most notable of these were the Legione Lombarda, Legione Italiana and eight Legioni Cisalpina. roughout the revolutionary period in Italy, 1796-1800 roughly 7,000 Italians served in these units. After the victory of Marengo in 1800, Napoleon reformed the Italian revolutionary formations, creating a regular army from the revolutionary cadres. Five mezza-brigata di linea (line demi-brigade) and two mezza-brigata leggiere (light demi-brigade) were established as the army of the Cisalpine Republic. Two cavalry regiments, 1 Cacciatore a cavallo (chaussers a cheval) and l Reggimento di Ussaro (hussars) were also raised.

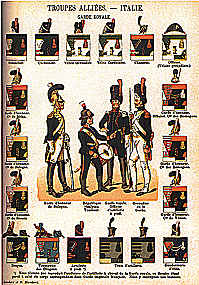

Garde Royale (Large: very slow: 214K)

Garde Royale (Large: very slow: 214K)

Garde Royale (Jumbo: extremely slow: 562K)

In 1802 the Cisalpine Republic became the Italian Republic, with a new constitution and a new President, Napoleon Bonaparte. It was at this time that the Italian army, originally all volunteer, adopted a conscription law based on the French Jourdan Law of 1798. The institution of conscription provided for an increased size of the army and was conducted with Napoleon's future plans clearly in mind. The first conscription law called for 6,000 conscripts annually, 3,000 in the active army and 3,000 in the reserve. By 1805 the Italian army numbered 20,000 infantry, cavalry and artillerists.

In 1806, the conscription quotas were increased to provide for 12,000 conscripts annually. This led to a dramatic increase in the size of the army, the number of regiments almost doubling. By 1811 the Italian army mustered seven Reggimento di linea, four Reggimento di leggiere, two dragoon regiments, four Reggimento cacciatore a cavallo, and Royal Guard consisting of the Granatieri, Cacciatori, Veliti and Reggimento del Coscritti. During the expansion of the army, specifically between 1805 and 1807 the Italian army maintained auxiliary light infantry regiments raised from the mountainous regions of northern Italy, the Cacciatori Reale Bresciani and the Cacciatori Istriani, raised in Dalmatia. All tolled the Italian army by 1812 was the largest of Napoleon's satellite armies.

While the Italian army was based upon the French model, Napoleon preferred to increase the number of battalions within the regiments rather than create entirely new formations. In 1812, therefore, with 80,000 men in the Italian army, they were divided between twelve infantry, three guard, and seven cavalry regiments in addition to the artillery and engineer corps. Originally the Italian regiments maintained two combat battalions and a third depot battalion. Shortly after the campaign of 1805 Napoleon authorized the establishment of a third combat battalion to the regiment. Due to a shortage of experience NCO's and officers, this task was not completed until 1808.

Only a few months later in 1809, Napoleon again ordered the expansion of the regiments to include a fourth combat battalion to the Leggiere and a fifth to the Lines. The strength of the battalions was generally larger than their French counterparts, roughly 750 effectives on campaign.

The rationale for maintaining a low number of regiments with a larger than normal compliment, was that it reduced the need for qualified officers and NCO's in the regiments. Throughout the Napoleonic era the Italian army always suffered from a lack of officers and NCOs.

Army Expansion

The expansion of the army occurred as follows:

| Year | Regiment | Battalions/ Squadrons | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 1 Linea | 2 (5)* | . |

| 1800 | 2 Linea | 2 (5) | . |

| 1800 | 3 Linea | 2 (5) | . |

| 1800 | 4 Linea | 2 (5) | . |

| 1800 | 5 Linea | 2 (5) | . |

| 1800 | 1 Leggiere | 2 (4) | . |

| 1800 | 2 Leggiere | 2 (4) | . |

| 1800 | 1 Cacciatore a cavallo | 4 | "Reale Italiani" in 1805 |

| 1800 | Artigliera a piedi | ** | . |

| 1802 | 1 Reggimento di Ussaro | 4 | . |

| 1803 | Granatieri delle Presidente | 1 | . |

| 1804 | 2 Reggimento di Ussaro | 4 | . |

| 1804 | Artigliera a cavallo | ** | . |

| 1805 | 2 Cacciatore a cavallo | 4 | "Principe Reale" |

| 1805 | Dragoni Napoleone | 4 | Formerly 1 Ussaro |

| 1805 | Dragoni Regina | 4 | Formerly 2 Ussaro |

| 1805 | Granatieri della | . | . |

| 1805 | Guardia | 2 | Formerly Presidente |

| 1805 | Dragoni della Guardia | 2 | . |

| 1805 | Guardia della onore | 1 | . |

| 1805 | Veliti della Guardia | 1 (2) | . |

| 1805 | Caccatori Reale Bresciani | 1 | . |

| 1806 | Cacciatori Istriani | 1 | To 1 & 2 Leggiere 1809 |

| 1808 | 6 Linea | 3 (4) | . |

| 1808 | 7 Linea | 3 (4) | . |

| 1809 | Reggimento | . | . |

| 1809 | Dalmazia Reale | 3 | . |

| 1809 | 3 Leggiere | 2 (3) | Formerly Reale Bresciani |

| 1810 | 3 Cacciatore a cavallo | 4 | . |

| 1811 | 4 Leggiere | 3 | . |

| 1811 | 4 Cacciatore a cavallo | 4 | . |

| 1811 | Coscritti della Guardia | 2 | . |

| * In parentheses the number of battalions per regiment by 1812. | |||

| ** The army's artillery were organized into one regiment of foot and one of horse, however, as the army expanded artillery companies were added to the regiments. | |||

Managing these regiments, regulating conscription and running the military administration was a task left to the Italian equivalent of Napoleon's Grande Quartier Generale (GQG). The Italian GQG was substantially smaller than its French counterpart, but by most European standards its was quite large. In 1811, after the completion of army expansion the Italian GQG numbered l,387 officers and personnel. Its success and efficiency can be seen in the ability of the army to expand and fill its ranks, as well as replace those lost on campaign.

COMPOSITION OF THE ARMY:

While the soldiers of the army were culturally homogeneous their social and political backgrounds were quite diverse. The Kingdom of Italy was formed from the former duchies of Milan, and Mantua, the Republic of Venic, the Paal Marches and parts of the duchy of Parma, the Austrian Tyrol, Italian Switzerland and the Kingdom of Piedmont. This regional diversity made initial attempts to forge a national army somewhat problematic. There was much dislike between Milanese and Bolognese, as well between Italians from the other regions of the kingdom. To reduce and eventually eliminate this dislike regiments were formed not upon regional grounds, but by military necessity. The officers, NCOs and conscripts from the twenty four departments of the kingdom were assigned to regiments based upon the manpower requirements of the unit. In time this produced a common bond among soldiers from all regions of Italy who served and fought side by side during the wars.

The officer corps of the Italian army was largely professional in nature. During its first years many officers were drawn from the Italian revolutionary legions and the army of the Cisalpine Republic. A considerable number of officers from Piedmont Tuscany, Parma, the Papal States, Naples and Corsica volunteered for service in the nascent Italian army. Beyond the small ducal armies, Italians serving with the Habsburg army in their "Italian" regiments deserted en masse during the conquest of Italy between 1796-1800 and joined the revolutionary legions.

These officers not only brought experience to the army, but provided a solid national foundation for the Italian army. In addition to officers drawn from the kingdom's departments and other regions of Italy, Napoleon transferred French officers to the Italian army. Most of these French officers were assigned to the revolutionary legions in the Year V (1797) and were originally NCOs in the Armee d'Italie. Remaining with the Italian army through the Italian Republic and kingdom, they rose through the ranks to become battalion and regimental commanders.

Officers indigenous to the kingdom were often found in the infantry regiments, while many of the "foreign" officers served in the Italian cavalry. Many of the French officers served in both infantry and cavalry units, but almost maintained a monopoly of command with the Italian artillery regiments. Only the regiments of the Guardia Reale were officered by a clear majority of Italians from the kingdom's departments.

At its height the Italian army required 5,000 officers. This number, however, was never fully achieved. Although in the army's formative years, 1801-1806, all 1,158 positions were filled, the expansion of the army outpaced the ability to produce officers. Military academies were established along the lines of the French military schools, but they were unable to recruit enough candidates. On the whole, officers were promoted from the ranks, especially the Veliti della Guardia, who were only initially formed to provide for future NCOs. Expediency and necessity dictated otherwise.

The Russian campaign was both the highlight and low point of the officer corps. More than 600 officers participated in the campaign of 1812, of these 350 were either killed or taken prisoner, with an even larger number receiving wounds, most of which were incurred at Malo-Jarosiavets in October 1812. But during these harsh days and those before the army reached Moskow, the status reports of the IV Corps of the Grande Armee indicated that virtually no officers were lost through combat or desertion. Only during the great retreat did their numbers even begin to dwindle. This was a credit to the officer corps, or what was left of it. In all, between 1805 and 1814, 1,173 officers, almost 20 percent of the total number who served were killed or wounded in the line of duty.

Of the rank and file there was a marked difference between professional and conscript. During the years 1796-1814, 44,000 Italians from every region of the peninsula volunteered for military service. Approximately half this number left the army after 1802, leaving 22,000 volunteers between 1803-1814, only 10-15 percent of the entire army. The balance, some 165,000 soldiers were conscripted in the years 1802-1814. The NCO corps was formed generally from the volunteers while the masses of men made up the army as a whole. This was not unusual, as the same was true of the French army after 1805.

Background

By and large the background of the common soldier differed from that of the officers. Whereas the officer corps consisted to a great extent of men who came from the cities of northern Italy, the rank and file was divided, almost equally between the urban and rural sectors. A mixture of peasant and farmer, artisan and urban worker populated the army. The practice of conscription followed the French model and each conscription class was called up every November in order for the recruits to be ready for spring campaigning. Supplemental conscription, however, was instituted several times, generally in an emergency, such as in 1813 when 24,000 young men were called, in addition to the annual levy.

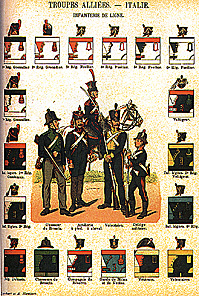

Infanterie de Ligne (Large: very slow: 229K)

Infanterie de Ligne (Large: very slow: 229K)

Infanterie de Ligne (Jumbo: extremely slow: 1004K)

The performance of these troops was mixed, and often depended on the region of Europe where their regiments were serving. On the whole, Italian regiments performed well when stationed in Italy, defending the kingdom. In Russia too the majority of the 25,000 Italians did well in both the advance and initial stages of retreat from Moskow. Even in Spain, the 10,000 Italians performed generally as well as their French counterparts. Yet, their perception as reliable troops did not negate the problem of desertion.

Desertion

In the Italian army roughly 15 percent of conscripts deserted, almost double the average French desertion rates. It can be said of the Italian army that when Napoleon and the Empire were scoring victories the soldiers and the Italian population were supportive of the military endeavors. When defeat struck, desertion increased and support for the Empire waned. During the Russian campaign the l5 Division Italienne lost 29 percent of its ranks to desertion by 1 August, and 57 percent by the time they marched out of Moskow in October. These figures match the desertion rates of the French divisions of IV corps. In 1813, there was a mixed reaction, as defeat brought war to the kingdom. The campaign in Italy in 1813-1814, witnessed large numbers of desertions, but conversely the ability of the army to replace those losses as quickly as they occurred.

Despite desertion, which plagued all armies of the Napoleonic period, the French and Italian generals had a favorable perception of the Italian troops. One of the greatest compliments was paid by General Antoine Lasalle. In 1807, he wrote, the colonel of the 1 Cacciatore Reale Italiani, stating that he commanded a "brave regiment...which distinguished itself." Lasalle continued, "they contended with the older French regiments for glory...it was my honor to serve with the general officers and have the regiment serve under my command. It was highly disciplined." During the same year, Napoleon complemented the Italian division on their conduct while besieging Colberg, telling its general that he had heard of the division's "esprit".

In 1808, in Spain, Italian troops were again complimented on their performance during the long and hot marches, as well as their conduct during the siege of Rosas. "...the young soldiers were as meritorious as they were brave..." wrote General Lechi, "they were patient and withstood privation." Even Sir Robert Wilson, a British observer with the Russian army commented after Malo-Jarosiavets, "the Italian army surprised me by their heroism."

One must not be swayed entirely by these comments. In general, the Italian army had its good days, and bad days. Their performance on campaign and in battle could vary, as did most regiments in the Imperial armies. They were, however, considered reliable and were a consistent part of Napoleon's armies. As a new national army, only officially created in 1801, the Italian army was a success, providing additional manpower for the Napoleonic wars. In this respect they made a considerable contribution to the Empire.

| SERVICE OF REGIMENTS OF THE ITALIAN ARMY: 1805-1814: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Theater of War | Army Designation | Corps or Division |

| 1805 | Italy | Armee d'Italie | Div. Fontanelli |

| 1805 | Italy | Corps d'Observation du Naples | Div. G. Lechi |

| 1805 | France | Armee du Angleterre | Div. Teulie |

| 1805 | France | Grande Armee | Imperial Guard |

| 1805 | France | Corps d'Observation (Channel) | Div. Teulie |

| 1806 | Italy | Armee d'Italie | Div Fontanelli |

| 1806 | Italy | Armee du Naples | Div. G. Lechi |

| 1807 | Italy | Armee d'Italie | Div. Pino |

| 1807 | Italy | Armee du Naples | Div. G. Lechi |

| 1807 | Germany | Corps d'Observation (Styraslund) | Div Teulie (Pino) |

| 1807 | Poland | Grande Armee | Div. Severoli |

| 1807 | France | Corps d'Observation | . |

| 1807 | France | de la Pyrenees-Occidentales | Div G. Lechi |

| 1808 | Italy | Armee d'Italie | 2 Divs + Guard |

| 1808 | Spain | Armee d'Espagne | VII Corps |

| 1810 | Italy | Armee d'Italie | 2 Divs + Guard |

| 1810 | Spain | Armee d'Espagne | VII Corps |

| 1811 | Italy | Armee d'Italie | 2 Divs + Guard |

| 1811 | Spain | Armee du Aragon | Div. Peyri |

| 1811 | Spain | Armee du Nord | Div. Severoli |

| 1812 | Italy | Corps d'Observation d'Italie | Depot Battalions |

| 1812 | Russia | Grande Armee | IV Corps |

| 1812 | Spain | Armee du Centre | Div Palombini |

| 1812 | Spain | Armee du Aragon | Div. Severoli |

| 1813 | Italy | Corps d'Observation de l'Adige | Assorted |

| 1813 | Italy | Armee d'Italie | I,II,III Corps' |

| 1813 | Germany | Grande Armee (remnants) | Assorted Battalions |

| 1813 | Germany | Armee du Elbe | XI Corps, Old Guard |

| 1813 | Germany | Armee du Main | IV Corps |

| 1813 | Germany | Grande Armee (reunited) | IV, XI Corps |

| 1813 | Spain | Armee du Aragon | Div. Severoli |

| 1814 | Italy | d'Italie | I, II Corps' |

Uniform Guides

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY:

The vast majority of information in this article was derived from the Archivio di Stato, Milano, Archivi Napoleonici, Ministero della Guerra (ASM) and the Archives de la guerre, Service historique de la armee du terre, (AG) Chateau de Vincennes, Paris.

AG:

-

C2 484. 8e Corps, Massena, 1805-1807

C2 527. IV Corps, Massena, 1812

C4 127. 8e Situations, Armee d'Italie et Armee du Dalmatie, 1806-1807

C17 200. Armee d'Italie, 1804-1813

Xl23. Legion italienne... Sept regiments d'infanterie de italienne

ASM:

-

45. Appendice = Storia = Corpi Italiani in Germania, Russia & Tirola

49. Appendice = Storia = Corpi Italiani in Spagna 1807-1810

51. Appendice = Storia = Reggimenti

391. Formazione de Corpi Legione Cisalpine

392. Formazione de Corpi Legione Cisalpine.

398. Formazione de Corpi Fanteria di Linea I Reggimento al 1810.

400. Formazione di Corpi Fanteria di Linea II.

402. Formazione di Corpi Fanteria di Linea III.

403. Formazione de Corpi Fanteria di Linea IV al 1811.

421. Formazione de Corpi Fanteria di Leggera II.

423. Formazione de Corpi Fanteria di Leggera IV.

456. Formazione de Corpi Dragoni Napoleone.

460. Formazione de Corpi Dragoni Regina.

461. Formazione de Corpi Cacciatori a Cavallo I.

462. Formazione de Corpi Cacciatori a Cavallo II.

463. Formazione de Corpi Cacciatori a Cavallo III.

464, Formazione de Corpi Cacciatori a Cavallo IV.

785. Leva - disposione generale, 1805

786. Leva - disposione generale, 1806.

793. Leva - disposione generale, 1809.

794. Leva - disposione generale, 1809.

795. Leva - disposione generale, 1810.

799. Leva - disposione generale, 1812.

803. Leva - disposione generale, 1813.

805. Leva - disposione generale, 1813-1814.

l067. Ministero della Guerra = Rapporti a S.A.I. al 1813.

1489. Leva - Personale Cov. - Cos.

2754. Stati di Situazione Divisione ed Armata in Spagna....al 1814.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 13

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com