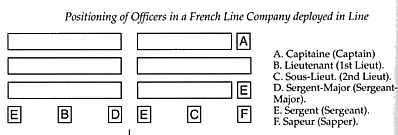

Positioning of Battalion Officers

INQUIRY BY KENNETH R. HAYNES JR.

There are two topics that are rarely addressed in discussions of eighteenth to nineteenth century tactics. Perhaps drill books of the period ignore them as far as I can tell.

(1) What were the positions of battalion and company officers in a column of route? The flags and drums?

(2) How could the regular companies of a battalion drawn up in close order, two or three men deep, advance through a body of woods and engage an enemy therein?

Many battles of the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries were fought in broken wooded terrain. With the exception of one very general article on this subject by Christopher Duffy, I have never seen the subject addressed. Even Brent Nosworthy's excellent Anatomy of Victory has nothing.

The British army deployed from an open order into little company columns called "double Indian files." Whether this column then deployed into an open order two or four deep line for combat purposes is beyond me. Several men from the wing sections of each company could have been thrown forward 20-30 yards as skirmishers.

Napoleonic armies in close order, shoulder to shoulder, could have opened ranks, then the men count off in threes. The ones became the pivot men as number two and three wheeled behind him. The three ranks would now be tripled to nine plus the file closer rank in the rear. This "wheeling by threes" is how I believe battalions in the War of the Spanish Succession prepared for advancing into woods. Each file would have some four to five feet between each other, ample room for winding a file of nine men between trees with minimal interference to one's neighboring files.

If a prolonged woods fight was inevitable, as at Abensberg in 1809, battalion commanders may have doubled or tripled their unit frontages before entering a forest. One section from each company could have been thrown forward "in great bands," while the other section followed as a reserve in loose files described above. As the drill books describe none of this (as far as I am aware) I suspect divisional commanders left such details to the judgment of regimental commanders. Does anyone have any better ideas or concrete knowledge?

ANSWERS AND COMMENTS

BY J. LOCHET AND THE EE&L STAFF

Because of the complexity of the subject covered, what follows are only sketchy comments and partial answers to the above questions.

On columns of route:

In theory, to form a column of march from a line, each individual would wheel to the right and form a column of three. But we should realize that a column of route was not necessarily a definite formation and could be formed from any type of column. Usually, the frontage of a battalion moving forward on a road-especially when close to the enemy-was dictated by the width of road on which the march was done. Most columns of route had a frontage ranging from three to six men and sometimes more.

When close to the enemy in open country, battalions very often moved in columns of companies or divisions in order to reduce the deployment time.

In French service during the Wars of the French Revolution and the Empire, the flag (and its Eagle [1]) in the line infantry was with the 1st Fusilier company and the officers and drummers (usually two per company) were at their assigned position in the companies, the battalion commander usually being in the front. The flag or standard varied from country to country but similar positioning of the battalion commander was also apparently applicable to the other nations.

Footnotes

[1] When a regiment had only one eagle, the eagle and the regulation flag was in theory carried by the 1st battalion, but the eagle had to be with the largest part of the regiment where the colonel was located. The other battalions had a fanion.

Part (2) of the inquiry: Infantry Deployments in Woods Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents #11

(Battlion Front faces bottom of screen)

© Copyright 1995 by The Emperor's Press