In EE&L #7, in Leona's Corner, we have seen how Napoleon generally behaved with women and how he alienated Madame de StaŽl who, from being anardent admirer, became his bitter enemy. We feel that more should be said about Madame de StaŽl's background to better understand her personality and behavior since she was deeply involved in French political life - like Talleyrand - from the Revolution to the overthrow of Napoleon.

In EE&L #7, in Leona's Corner, we have seen how Napoleon generally behaved with women and how he alienated Madame de StaŽl who, from being anardent admirer, became his bitter enemy. We feel that more should be said about Madame de StaŽl's background to better understand her personality and behavior since she was deeply involved in French political life - like Talleyrand - from the Revolution to the overthrow of Napoleon.

Anne Marie Germaine Necker was born in Paris on April 22, 1766 from Swiss parents. Her father was Jacques Necker, the finance minister of Louis XVI, and her mother, Suzanne Curchod, considerably helped her husband in his career by establishing a brilliant literary and political salon in Paris. The young Germaine Necker gained early in life a reputation for lively wit, if not for beauty. While still a child, she was to be seen in her mother's salon, listening and even taking part in the conversation with the lively intellectual curiosity that was to remain her most attractive quality.

She was married in 1786 to the Swedish ambassador in Paris, Baron Eric de StaŽl-Holstein.

Then, came the Revolution. Madame de StaŽl admired Montesquieu, one of the preeminient liberal philosophers, and under his influence as well as her father's she adopted political views based on the English parliamentary monarchy and favored the Revolution. She acquired a reputation for Jacobism and, under the Convention, the Girondin (moderate, liberal) faction corresponded best to her ideas. In the beginning, protected by her husband's diplomatic status, she was in no danger in Paris, but, soon, she became a suspect and was even interrogated by the Republican Tribunal. [1] She prudently retreated to the family estate in Coppetnear Geneva in Switzerland, where she established a meeting place for some of the leading European intellectuals.

Like many of her contemporary society women Madame de StaŽl was not a model of virtue either. In 1789, she became the mistress of one of Louis XVI's last ministers, Louis de Narbonne. To save his neck, he took refuge in England in 1792, where she joined him in 1793. She stayed at JuniperHall, near Mickeleham in Surrey. There she met Fanny Burney (later Madame d'Arblay), but their friendship was cut short because Madame de StaŽl's political views and morals were considered undesirableby good society in England.

She returned to France via the family estate in Coppet. At the end of the Reign of Terror, in 1794, she established another flourishing salon in Paris.

Brilliant Career

A brilliant period of her career started. She published several political and literary essays among which is De l'influence des passions [2] (1796). She began to study the new ideas being developed particularly in Germany. It is Henri Benjamin de Constant Rebecque, her new lover, who influenced her most directly in favor of German culture. Her fluctuating liaisons with Constant started in 1794 and lasted for fourteen years. It is alleged that he is the father of Albertine de StaŽl born in 1796.

Her marriage to Baron de StaŽl was a marriage of convenience which was ended in 1797 by formal separation.

Among her many lovers was Talleyrand. That relationship had started much before Talleyrand [3] was exiled to the United States and continued through a somewhat abundant and passionate correspondence too lengthy to quote here. She was instrumental in helping Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand to come back from exile. [4] Following are some extracts of letters that give a pretty good idea of the relationship between Talleyrand and Madame de StaŽl. On September 8, 1795, Talleyrand from New York wrote to Madame de StaŽl:

"I have great need, dear friend to receive your letters....In my last letter that is perhaps at the bottom of the sea, I talked about the children of Madame de Perigord [5] and I would ask you to do whatever is possible for them....I am resolute to go back to France in the spring....Farewell, dear friend, etc."

Then, after he received the news that he was allowed back to France, Charles Maurice on November 14, 1795, wrote from New York:

"So, thanks to you, dear friend, that matter is closed to my complete satisfaction. I wanted the Convention,that had accused me to recede her decree....In the spring I will leave the USA for the port of your choice, and the rest of my life, in a any place you'll inhabit, will be spent near you....Will Madame de StaŽl give me a small bedroom in her house?...Farewell dear friend, I love you with all my soul."

In Disgrace

Well that is to the point. Thirteen years later, Madame de StaŽl, [6] in disgrace, wrote to Talleyrand, begging him to intercede in her favor with Napoleon to allow her to return to Paris and forget her offenses. With great thoughtfulness she reminded Charles-Maurice of his pledge of love when he was in exile in the U.S.A.:

"You will be surprised to receive a writing you have forgotten....Thirteen years ago you wrote me from America 'If I stay one more year here, I'll surely die....' I could say the same for myself for being in a foreign land: I am slowly dying, but the time for self-pity has passed, necessity has taken over. Please, see, if you can help my children...."

At the news that Talleyrand was coming back to France, Madame de StaŽl even made plans to meet Charles Maurice at the port of his disembarkment. On April 17, 1796, she told her new lover Mr. de Ribbing that she will have to travel in the beginning of the summer because "my friend from America wrote me that he'll arrive in early June...." That was a superfluous measure, as she soon broke off her relationship with the handsome Swede about whom Talleyrand [7] later ironically said: "That Mr. de Ribbing, from which you wrote me so much good while in America, appeared to me as very little, he is handsome in the fashion of the old servant of Mr. de Poix, but concerning his intellect, he is not very much."

Talleyrand reached Hamburg on July 31,1796, where he spent a month in the company of his friend Karl Henrich grafvon Reinhard and the Comtesse de Genlis. Reaching Paris on September 20, he immediately occupied at the Institut National the seat to which he had been elected the previous December. Although the Directors, with the exception of Barras, despised Talleyrand, on the insistence of Madame de StaŽl, in July 1797, the latter became foreign minister. Talleyrand owed much to Madame de StaŽl, but later became ungrateful and did not respect his pledge to spend the rest of his days near her.

Wit

The following are a few anecdotes showing Madame de StaŽl's wit and inquisitive mind that are worth telling.

If Madame de StaŽl became Napoleon's enemy that was not always the case. Since she came back to France in 1794, she had witnessed the evolution of the political life and, in 1797, Bonaparte still seemed to her the epitome of the hero who would bring peace and sanity back to France. We have seen that she pursued and flattered him constantly but that he eluded her whenever possible. A question comes to mind: Was Madame de StaŽl trying to add Bonaparte to her numerous conquests? That is certain, but, at that time, Bonaparte was still passionately in love with Josephine, so Germaine's advances remained completely ignored. While her overdone flattery had inspired him with an aversion toward her, he still received her while he was First Consul, but he answered her importunities with coldness. Baron de Meneval is of the opinion that the contempt for her advances was sufficient - although it has been said that some financial interest was mixed with it to change Madame de StaŽl's devotion into an antipathy which so on revealed itself in open opposition.

On one occasion, she called on Bonaparte's house demanding to be admitted at once to his presence. The butler explained that was impossible sincethe general was in his bathtub. "No matter," Madame de StaŽl cried, "Genius has no sex!"

In 1803, Madame de StaŽl published her feminist novel Delphine, in which she herself appears, flimsily concealed, as the heroine. The opinions and characters of Talleyrand were embodied in the fictional figure of the book's villainess, Madame de Vernon. When Talleyrand next saw Madame de StaŽl, he greeted her with the words, "They tell me we are both of us in your novel, in the disguise of women."

Talleyrand never missed an opportunity to tease Madame de StaŽl. Her officiousness could be a trial even for her friends. Talleyrand remarked that she was such a good friend that she would throw all her acquaintances into the water for the pleasure of fishing them out.

Another time Talleyrand was sitting between Madame de StaŽl and the famous beauty Madame Rťcamier (see EE&L #5 on page 24 for a picture of her), his attention very much engaged with the latter. Madame de StaŽl made a bid to get into the conversation: "Monsieur de Talleyrand, if you and I and Madame Rťcamier were shipwrecked together and you could save only one of us, whomwould you save?" Talleyrand replied with his deepest bow, "Madame, you know everything, so clearly you know how to swim."

Madame de StaŽl told the story of how she and beautiful Madame Rťcamier were seated at dinner on either side of a young fop, who announced, "Here I am between wit and beauty."

"Quite so," said Madame de StaŽl, "and without possessing either."

By 1800, Madame de StaŽl's literary and political character had become clearly defined. [8] But she was also important politically. The merited literary reputation which she enjoyed, her virile talents, her passion for fame, her irresistible mania for meddling with the affairs of the government, her quarrelsome nature, the charm of her conversation - which always sparkled with flashes of wit - had given her an influence over the political men of the period which she abused. With Constant de Rebecque and his friends she formed the nucleus of a liberal resistance.

Napoleon put up with her continual hostilities for three years during which she had treated his warnings and notices with contempt. In fact it appears that this tolerance had encouraged her to stir up opposition against him on every side. Her salon had become a political club where the acts of the government were bitterly censured, and where, without any concealment, people were urged on to open revolt against the authority of the Head of the State. Her actions so embarrassed Bonaparte that in 1803 he had her banished to a distance of forty miles (sixty four kilometers) from Paris. Her anti-Napoleon stand did not stop there.

But this woman who could not endure an existence far from salons and the theater on which her active mind wished to bestir herself, took recourse to the most urgent solicitation to be allowed to return to Paris. She even managed to come close to Paris. She knocked on every door to no avail but was forced to return to Coppet the victim of her nature, and whose judgment, as Napoleon used to say, [9] was not on the level with her brilliant imagination and rare faculties.

Several new liasons were made and broken off at the retreat in Coppet to while away her leisure hours. Among her new conquests were the son of Prefect of Geneva M. Barante [10] and the Prince Augustus of Prussia.

Letters By Napoleon

Two letters from Napoleon showing the Emperor's feelings about Madame de StaŽl and her seditious friends are worth quoting. The first one is from Pultusk on December 31, 1806 and is addressed to:

"Monsieur Fouchť, Minister of the General Police in Paris,

"Monsieur Fouchť, if M. Chenier permits himself to make the slightest remark, inform him that I shall give orders for him to be sent to the St. Marguerite Islands. The time for fooling has passed by. Let him keep quiet; it is only right. Don't allow that rascally Madame de StaŽl to approach Paris. I know that she is not far from it."

The second letter was addressed to Marshal Victor who was governor of Berlin and is dated December 6,1807:

"My cousin, I am in receipt of the letter in which you inform me that Prince Augustus of Prussia is misconducting himself in Berlin. It does not surprise me, for he is a man of no intelligence. He spent his time making love to Madame de StaŽl, at Coppet, and could gain none but bad principles there. He must not be overlooked. Inform him that the very first time he says anything, you will have him arrested and locked up in a fortress, and that you will send him Madame de StaŽl to comfort him...."

In 1808, she tried to regain Napoleon's favors to no avail by writing to Talleyrand, but he could do little as Napoleon's hostile feelings toward Charles Maurice's former mistress were too deeply rooted.

In 1810, the Emperor ordered the notes concerning several people in the Faubourg St. Germain, [11] whose removal Fouchť had demanded. He was surprised at the trifling nature of the complaints made against some of them, and ordered that these persons should be recalled from exile. Four or five of them alone were excepted, among these Mesdames de Chevreuse and de StaŽl. The Emperor, deeming them incorrigible, and along with the beautiful Madame Rťcamier, now one of Madame de StaŽl's henchwomen, confirmed their exile and forbade them to live in Paris in the strictest terms.

Madame Rťcamier had been drawn over to the opposition by Madame de StaŽl, and by her own animosity against the Emperor. This was the reason of her enmity:

Monsieur Bernard, Madame de Rťcamier's father, director of the post office, had lent his name and patronage to a periodical edited by one of his friends, the Abbe Guyot, which attacked the government, the First Consul and his family. He was arrested. His daughter protested his innocence in vain. Bernard was found guilty but instead of being sent to prison was simply dismissed. The Rťcamier firm having failed during the financial crisis of 1806, Madame de Rťcamier was forced to leave Paris, which she visited from time to time, spending the rest of her time in Coppet, from where she brought with her the quarrelsome spirit of Madame de StaŽl and her coterie. Consequently, she found herself involved in Madame de StaŽl's disgrace. The latter was flattered at being able to hold in bondage a woman celebrated for herbeauty, who was the object of the admiration of all the fashionable world. It delighted her to hear people say that the connection of the two women, one famous for her graces and the other for her wit, was the alliance of genius and beauty.

During Madame Rťcamier's stay at Coppet, Prince Augustus of Prussia, [12] fell violently in love with her, and went so far, it is said, to sign a promise of mariage. [13] Madame Rťcamier was not banished. She had condemmed herself to voluntary exile in the provinces. It was only after she began to take active part in Madame de StaŽl's opposition that she was forbiden to return to Paris. After three years spent at Chalons Lyons and Geneva, she made a journey in Italy. She did not return to France until 1814.

Madame de StaŽl's work De l'Allemagne (1810) on German Romanticism was considered by Napoleon as anti-French and the French edition, 10,000 copies, was seized and destroyed. It was finally published in England in 1813.

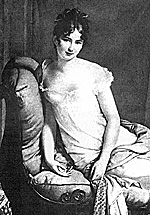

Picture: Madame Recamier as painted by Gerard

Madame de StaŽl, now prosecuted by the police, fled from Napoleon's Europe. Having married a young Swiss officer "John" Rocca, [14] she went to Austria, Russia, Finland and Sweden and, in June 1813, arrived in England. She was received with enthusiasm, but liberals like Byron reproached her for being more anti-Napoleonic than liberal, and the Tories criticised her for being too liberal.

In 1814, upon the Bourbon restoration, she returned to Paris but was deeply disillusioned. During the Hundred Days she fled once more to Coppet. She returned to Paris, but her health declined and she died in Paris on July 14, 1817.

After 1808, Madame de StaŽl knew no limits. She wrote another book expressing her bitterness and hoped that France should suffer reverses which would open her eyes to the facts that Napoleon was the author of all her troubles. She wrote another book entitled Ten Years in Exile, which was printed after her death. After the title was written: "A work written to justify Napoleon's persecution of the authoress."

Sources:

-

Blanc, Louis, Histoire de la Revolution Francaise, Paris, date unknown.

Connelly, Owen, The French Revolution and Napoleonic Era, 1991

Duchť, Jean, L'Histoire de France racontťe ŗ Juliette, MacMillan, NY, 1987.

Mťneval, Baron Claude-FranÁois de, Memoirs of the Baron of Mťneval, NewYork, 1894.

Poniatowski, Michel, Talleyrand aux Etats-Unis, Presse de la Citť, Paris, 1967.

Footnotes:

[1] Between March 1793 and June 10, 1794, Robespierre's Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris alone sent 1,251 victims to the guillotine, but between June 10 and July 27 (9 Thermidor), in six weeks, there were 1,376 executions! That was the Grande Terreur and everyone felt threatened.

[2] De l'influence des passions (1796), is considered as one of the important documents of European Romanticism.

[3] Talleyrand favored the Revolution and became part of the Convention. In 1793 he was sent to London in an official mission but while there was declared an emigrť. Because of his political views, shorthly after, he was expelled from England and took refuge in the USA in 1794 (Philadelphia, New York, etc.) where he remained until 1796.

[4] Madame de StaŽl authored the plan to reintegrate Talleyrand into French society. With Madame Tallien and her husband, she tried to recruit in the Convention enough members to support the motion of Talleyrand's recall: Cambares, Dubois-Dubay, Genisson, Boissy d'Englas, Barras, Gregoire, Carat, Guinguene, etc. Talleyrand's cause was argued by Chenier. Marie Joseph Blaise de Chenier, (1764-1811) was the brother of Andre Chenier who was guillotined on July 25, 1794. He was a member of the Convention, who, besides being a politician, was also a dramatist and a poet. He authored numerous patriotic hymns among which is the famous Chant du Depart.

[5] Madame de Perigord was Talleyrand's sister-in-law. Her husband had been guillotined during the Terror and she found herself without resources. Madame de StaŽl, at Tallerand's request, helped her.

[6] Letter from Madame de StaŽl to Talleyrand dated April 3, 1808.

[7] Letter from Talleyrand to Madame de StaŽl dated February 18,1797.

[8] Her literary importance emerged with De la litterature consideree dans ses rapports avecles institutions sociales (1800), Delphine(1802), and Corinne (1807), etc.

[9] Meneval, Vol. 2, p. 13.

[10] During the course of this magistrate's frequent visits to the Chateau de Coppet, his son made the acquaintance of Madame de StaŽl and captivated her with his remarkable intelligence. To such a degree was she affected that when the younger Monsieur de Barante left Coppet to go to Paris, Madame de StaŽl tried to commit suicide.

[11] The area of Paris in which the famous salons were located. On the same occasion, Napoleon, wishing to inform himself on what was the real state of affairs in the Faubourg St. Germain, ordered investigation of some influential families who were known for their active opposition against the new order of things.

[12] Prince Augustus of Prussia was the son of Prince Ferdinand and nephew of the great Frederick.

[13] The promise was returned but the Prince remained attached to Madame Rťcamier. It was for her that he ordered from the painter Gerard the fine picture of Corrina's improvisation at Cape Misene.

[14] Rocca's account of his service in Spain has been published by Greenhill Press as In the Peninsular with a French Hussar.