The staff answers questions on French civilians during

the 1814 campaign, and the organization of Napoleon's cavalry

I. A QUESTION ON EE&L #6

from Art GreenfieldIn reading the excellent article on the Battle of Saalfeld in EE&L #6,I was puzzled by the second paragraph quotation on page 22. Something appears to be missing. Am I right?

II. ANSWER TO THE ABOVE QUESTION

by the EE&L StaffYes, you are correct. The beginning of the quotation was left out. The full text of Frederick William quoted from Foch is as follows:

"That the theory of the decisive attack had been perfectly grasped by the Prussians of 1813, from studying the wars of the Empire. Proof:

"Instructions For Officers Commanding Corps, Brigades, etc. Delivered by King Frederick William During the Truce of 1813:

Picture: Our advisor, Frederick William III of Prussia. Napoleon described his wife as being the "only man in Prussia."

"As it has come to my notice that, during actions and battles, the various arms have not been always conveniently brought into action and that dispositions in view of battle are generally unsatisfactory, I desire upon the occasion of the coming resumption of hostilities, to recall the following rules of war:

"These are the general principles: [Note that some of these principles, numbers three through five, are missing in Foch's quotation]

"(1) In view of the manner in which our enemy is making war, it is generally unwiseto begin a battle with cavalry, or to bring all the troops immediately into action. Owing to the way in which he uses his infantry, he succeeds in delaying and supporting the action; he carries villages and woods, hides behind houses, bushes and ditches; he knows how to defend himself skillfully against our attacks by attacking himself; he inflicts on us losses with a few troops, when we advance against him in great masses; he then relieves those troops, or sends freshones into action and, if we have no fresh troops to oppose his, he compels us to giveway. We must draw from this principle, which is the enemy's, that we must spare our forces and support the action until we turn to the main attack.

(2) Our artillery has not produced a great effect, because it has been too much divided

(6) War in general, but above all, the issue of battle, depends upon superiority of forces on one point.

(7) In order to secure this superiority of forces, it is necessary to deceive the enemy concerning the real front of attack and to make a false attack and a real attack.

(8) Both attacks must be masked by skirmishers, so that the enemy should be unable to distinguish the difference.

(9) A line of skirmishers is first of all to be sent out. The attention of the enemy is to be drawn by several battalions designed to fire on one of the wings, on which guns must be firing heavily at the same moment. Battle must be ordered in that fashion.

(10) Meanwhile, the real attack is still postponed and it only begins later on, at the moment when the enemy's attention is entirely turned on the false attack.

(11) The real attack is made as quickly and as vigorously as possible and above all by a large mass of artillery and infantry,of a superior force, if possible, while aparticular corps goes round the enemyflank....In principle, a commander shoulddevote one brigade to the false attack, twobrigades to the real one and have onebrigade in reserve.

"These are principles which are wellknown to you and which have beenseveral times recommended. We have putthem frequently into practice in our peace maneuvers but I remind you of them, because what is known is sometimes forgotten, because though a simple thing may seem to be commonplace, yet victory often depends upon it. Unless one is careful to recall it everyday to mind, one indulges in combinations which are too scientific, or, what is worse, one goes into battle without having taken any disposition whatever."

Then Foch goes on to his own conclusions:

"As we see, after explaining the theory of the preparatory attack, or false attack, and of the decisive attack, which he calls the real attack, after showing by what kind of actions this theory must express itself,the King states, in order to make more precise for the use of undecided minds: 'Out of four brigades, you shall devote one in the false attack, two to the real one and one to the reserve.' Later on, a perfect plan will lay down the formula: a third in order to open, a third in order to weardown, and a third in order to finish."

FURTHER NOTES ON EE&L #6:

The previous quotation is very important to the wargamer since the King of Prussiahad set down the principles for winning a battle. In addition, all the true principles of battle have been presented to us. We just have to apply them, providing we have our own self-discipline to obey the principles (see what the King says) and also realistic rules that allow us to practice them (and that is far from a sure bet!).

III. SOME QUESTIONS ON THE TRAINING OF NAPOLEON'S GRANDE ARMÉE OF 1813

from Nigel Ashcroft

I have recently read Scott Bowden's Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813, which highlights the conscript quality of the French troops and their limited tactical deployment ability. On page 62, Mr.Bowden quotes Napoleon's correspondence to Lauriston "....manoeuvres of change of formation from attack column to square and back are recommended, exercise the battalions in column of attack...."

Having read many of the articles in previous issues of EE&L with regard to the deployment of troops, I am a little confused with the reference to an Attack Column or Column of Attack. Does this refer to a column formed on the middle division (e.g. Companies 3 & 4 in the 1808-15 battalion)? Or is the term used loosely to suggest that the attack is made in column (formed on Companies 1 & 2), e.g.,is this type of column being used as an attack formation rather than a waiting and manoeuvre formation? Was it no longer possible to get the troops into position in column and then deploy into line (which is the trend that I interpret from your previous articles)? Also it seems at variance that this column used would beformed on the middle, as it is necessary to go from column of route to line to form this type of column, some thing beyond the conscripts ability. I raise this point so that it may be clarified for other readers of the book who may not have the benefit of all of your other articles.

IV. SOME COMMENTS ON THE TRAINING OF THE GRANDE ARMÉE OF 1813

by J. Lochet and the EE&L Staff

So much has been written on the poor training of the French infantry in 1813 that we have a tendency to generalize too much. We have accepted, perhaps unconsciously, the different negative interpretations that we have been bombarded with in the past by numerous inaccurate sources. Thus, in the process,we have generally ignored the primary sources that, if properly studied, mightserve to dismiss the prevailing myths.

I must confess that we were very skeptical about the Grande Armée of 1813 being capable of using the column of attack (or column on the middle) on a regular basis. Many of us have a tendency to forget that Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813 was far from homogeneous in terms of training and quality of troops. Tactical formations (and here I mean battalions, brigades and Divisions) ranged widely from Old Guard quality to untrained militia. Scott Bowden in his Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813 covers that point extensively.[1]

At Historicon 94, I spoke to Scott Bowden and George Nafziger on the training of the Grande Armée of 1813 and, in addition, I re-investigated the question using a profusion of primary and secondary sources.[2] Both Mr.Bowden and Mr. Nafziger sent us a copy of the primary source quoted by Scott Bowden in his Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813 which was a direct quotation of Napoleon's Correspondence No.19775 dated Paris, March 27, 1813 to General Bertrand commanding the IV Corps. The translation (the French original is included on the next page) reads as follows:

"A square can be formed indistinctly on any divisions of a troop in line, parallel or perpendicular to that line, and according to the circumstances and condition of the ground; there is, in the appendix of the Ordinance, a comment given, I believe in 1805, that clarifies the subject completely, but it is important to familiarize the troops with it and to close in the serre-files on the third rank, the square being formed and the cavalry trying to break it. It is desirable that a company of voltigeurs always have a reserve on which it may rally, when it becomes unable to withstand a charge when deployed in skirmishers.

Picture: Conscripts of 1813 by Sergent

"The colonne d'attaque will always be formed according to the principles of the Ordnance, but, if the line has to advance forward in that order, the first division, or forward division of each column, with bayonets at the ready, and, after reaching the point where the line must stop, these same forward divisions [divisions de fete] will open fire from two ranks, and the columns will deploy under the cover ofthat fire. [See diagram below, JAL.]

"I desire in that maneuver a quicker action that the regulation calls for, that is each platoon shall open fire as soon as it arrives on the line, and that the guides must be eliminated.

"If one has to redeploy his line to form acolonne d'attaque while the entire line is firing, the redeploying action can be done under the cover of the fire of the forward divisions, but then, the commander of each battalion, by his adjutant-major and his adjutants, shall inform the platoon commanders on the wings of the maneuver that they shall perform, the drum command to cease fire not having been given. The charge shall be beaten only when facing the enemy, or during maneuvering, and always in the simplest form, that is the most impressive. The firing practice on target is good; it is important to fire individually very much and to give some recognition to the best ones."

The above translation is in full agreement with Mr. Bowden's quotation in Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813 (on page 62). It is quite to the point and the quote sheds a great deal of light on the training of the Grande Armée of 1813, which, as mentioned above, was unevenly trained. Bertrand's IV Corps consisted of very good troops.[3] There is little doubt that all the regular line infantry regiments were properly trained in this type of maneuvering and all had received target practice.[4]

Similar letters putting the emphasis on forming squares, the column of attack, etc. were sent to Ney, Marmont, and Macdonald, to name a few.[5] Scott Bowden covers that extensively from primary sources (pp. 62 to 66) and quotes General Girard's report on April 24: "The battalions of my division can rapidly deploy from attack column to square and reform into attack column. But God help us if anyother formation is asked."[6]

So, basically, all the regular infantry regiments in the spring of 1813 could perform the basic deployment into line,[7] column of attack, and square and redeploy back into a column of attack as prescribed by Napoleon. And there is ample primary evidence that Napoleon's instructions had been carried out. What it boils down to from all these primary sources is that these battalions had been trained as per the Reglement through the battalion school, but had not received training in the regimental or brigade schools.

Prior to 1813, Napoleon's generals had been in the habit of choosing their own formations. That came to a end in 1813 and Bowden is once more to the point when he says:

"Inflexibility with the choice of formations used by the infantry was something new to the corps and division commanders in Napoleon's army. In the earlier years of the Empire, highly trained Napoleonic infantry were able to rapidly deploy in many more formations than just attack columns and squares, they were able to deploy in a number of other formations as well as effectively maneuver by regiments and by entire brigades. Being able to move in combat in multi-battalion and multi-regimental formations of many combinations offered enormous tactical flexibility and advantages, especially when pitted against opponents whose choice of formations and concept of coordination often times did not go above theregiment." (page 64)

It is a very important point worth emphasizing. The battalions had been drilled in the basic formations mentioned above as per the School of the Battalions[8] but were lacking in drill at higher levels. This fact is also well covered in Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813:

"With the rebuilding of the army in 1813, the French marshals and generals needed the time to teach their new infantry multi-battalion maneuvers. This was particularly difficult to achieve, owing the lack of officers and non-commissioned officers, and to the short period of time with which the army had to drill its formations before war broke out.

"General Lauriston voiced a strong opinion about the level of regimental drill on April 15, when he wrote to Prince Eugene about his regiments, which will be remembered were comprised entirely of old cohorts. 'His Majesty must reasonably believe that, from the time the cohorts were brought into a regiment, there must exist teamwork in maneuvers and in the make-up of the regiments; that does not exist at all.' Since all corps commanders were struggling to bring the level of drillup to regimental coordination, brigade drill for the new regiments was impossible. Except for the regiments of the Old and Middle Guard, as well as the 1st Regiments of the Young Guard Tirailleurs and Voltigeurs which were reconstituted with the instructional battalions of Fontainebleau and veteran 3rd Regiments of the Young Guard Tirailleurs and Voltigeurs, the entire army went to war in late April 1813, with its infantry only being able to maneuver by battalion." (page 64)

This may be the point many English language historians were trying to make when they claim that Napoleon's army in early 1813 lacked training. But we are speaking of degrees of training. The army did lack training at the regimental, brigade and Division levels but not at the battalion level, which is quite a difference from the sweeping assertions that the French conscripts were completely incapable of maneuvering.

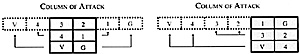

Another question comes to mind. Why was the Column of Attack (also known as column on the middle) preferred to the easier formed Column of divisions? The answer is provided by taking a quick look at the two drawings on page 34. Note that the two columns both have a 2-company frontage but that the arrangement of the companies is different. For that reason:

(1) The column of attack is faster to deploy than the column of divisions; and

(2) The companies come into firing position sooner than they did using the column of divisions, which is precisely what Napoleon was looking for as he wrote to Bertrand in his letter quoted previously:

"The colonne d'attaque will always be formed according to the principles of the Ordinance, but, if the line has to advance forward in that order, the first division, or forward division of each column, with bayonets at the ready, and, after reaching the point where the line must stop, these same forward divisions (divisions de tete) will open fire from two ranks, and the columns will deploy under the cover of that fire.

"I desire in that maneuver a quicker action than the regulation calls for, that is each platoon[9] shall open fire as soon as it arrives on the line...."

Drawing: Comparing the deployment of a Column of Attack (or Column on the Middle) and of a column of divisions. The Deployment of the Column of Attack is slightly faster than the deployment of a column of divisions, and, when deploying into line, the deployment from the Column of Attack can be made under the protection of the middle division which is already in firing position. Such is not the case with a column of divisions.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that overall the new Grande Armée of 1813 lacked training, but that lack of training was not as bad as we have been led to believe.

Let us not forget that it's with this imperfect tool that Napoleon won Lutzen and Bautzen in the spring of 1813, as well as a string of lesser engagements.

Napoleon said: "The armistice stops the progress of my victories." It was not his infantry, but rather the state of his cavalry that persuaded him to accept an armistice.

Let us not generalize too far either. What we said above is only pertinent to the Grande Armée in the spring of 1813, and that army only fought for about two months, from very late April to June 4.

The armistice extended from June 4 to August 16, and, during that time, the commanders and troops worked very hard at improving the training level of the army. Once more, the results varied greatly from Corps to Corps,'[10] but that is a topic for a future issue.

We hope the above explanations will shed some light on the drilling and training of Napoleon's infantry in the spring of 1813 and help correct some of the errors perpetuated by many English language historians.[11] Once more, let us point out that the best sources to study French army drill are French primary sources and reliable secondary sources using French primary sources. We are happy to report that Scott Bowden's Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813 [12] fully qualifies as a reliable secondary source.

Footnotes:

1. The subject is covered mainly in Chapters III, IV, V, etc., and in Appendix Z.p. 342.

2. We are speaking here exclusively of secondary sources carefully using primary sources. Scott Bowden's Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813 is one of them.

3. See IV Corps order of battle p. 216 and Appendix Z. pp.343-344.

4. We do not generalize. It is doubtful that most of the temporary regiments and their like had been fully trained. Some may have even lacked musketry training.

5. See Correspondences 19775, 19714, 19553, etc.

6. General Girard to Ney,24 April, 1813, Archives du Service Historique.

7. The battalions were also able to deploy into line since in order to form an attack column a battalion has to deploy from column of route to line then redeploy intoan attack column.

8. The Reglement of 1791 included several training stages called schools. It started with stage 1: Ecole de bataillon' (battalionschool), i.e.,. basic drill for the battalion, followed by the Ecole de regiment (regimental school), i.e., basic regimental evolutions with more than one battalion, followed by brigade drill, i.e. evolution by brigades, and so forth.

9. In the French infantry of the period, each company only included one platoon so the terms company and platoon are interchangeable.

10. See Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813, pp. 111 to 137.

11. See for instance, Petre, Napoleon's Last Campaign in Germany.

12. Scott Bowden, Napoleon's Grande Armée of 1813, The Emperor's Press, Chicago, Illinois.

Picture: A conscript in his hirst action, by Raffet

V. QUESTION ON RAIN AND THE ABILITY OF INFANTRY TO WITHSTAND A CAVALRY CHARGE

also from Nigel Ashcroft

This question is a wargame effects one, based on Mr. Bowden's book. I read with interest the terrible weather that the troops suffered during the 1813 campaign. The occurances of infantry in square being unable to withstand cavalry (especially Lancers) seem to have drastically increased. Whether this phenomenon was due mainly to the weather (and the subsequent demoralising effects of not being able to shoot at the cavalry), or to the poor quality of the French troops of this period is not clear. What do you feel is the effect of persistent rain on the ability of infantry to withstand cavalry in square? So far, I have not found any references to rain changing the tactics or grand tactics used in battle.

VI. ANSWER TO QUESTION ON RAIN AND INFANTRY SQUARES IN THE 1813 CAMPAIGN

by J. Lochet and the EE&L Staff

Constant rain and empty stomachs are by no means morale boosters. In addition, there is little doubt that the quality of infantry affected its ability to withstand a cavalry attack. Undoubtedly, so did the weather. But neither the weather nor inexperience were the exclusive problem of the French, and both sides suffered accordingly. Veterans knew they had nothing to fear from cavalry while in square. That is at least true when the weather was good and muskets could be fired. However, it was an entirely different story when the powder in the pans of the flint-lock musket were saturated by the rain, preventing infantry from firing their weapons.

The situation was very bad for the Austrians on the Allied left during the last phase of the Battle of Dresden (August 27, 1813). It had been raining steadily since the morning and what took place is well-illustrated by General SirEvelyn Wood in Achievements of Cavalry, London 1897:

"This action gave rise to several remarkable scenes. General Bordesoule confronted a brigade of Aloys Lichtenstein's division, formed in square. The French commander, riding in the front, summoned the Austrians to surrender, saying, 'Your muskets won't go off!'

To which their leader replied, 'Surrender! Never! If our muskets won't go off, your horses cannot charge in mud upto their hocks.'

'That is right,' replied Bordesoule; 'but I will blow you to atoms with my guns.'

'You have got none up with you,' replied the Austrian.

'Yes, I have' was the reply, and a battery of horse artillery trotting up, unlimbered within 100 yards of the square. The Austrians seeing the French gunners standing with lighted port fires in hand, realized the impossibility of further resistance, and surrendered.

"During the struggle of Horsemen against Footmen, who were unable to fire, several expedients were adopted in order to break the ranks of the steadfast Austrian infantry.... One square was broken by the expedient of sending forward Cuirassiers with drawn pistols[1], who riding close up to the ranks, shot the infantry, and then, being followed by squadrons in mass, broke in over the fallen bodies." (pages 92-93)

Then on page 94:

"...the squadrons found themselves in front of an Austrian battery, flanked on either side by two large squares. The battery opened fire as the French cavalry appeared, but their guns were laid too high, and the only loss at this time inflicted on the cavalry was caused by a party of Riflemen posted in a ravine behind some trees. Possibly they had another type of firearm,[2] which would have been more serious had not a French infantry column appeared at that moment, which attacking the Riflemen, drove them off. The French cavalry now advanced on the squares, and the battery, abandoning its infantry, limbered up, and drove off. Twice the attack, which was made at the walk, failed, the Austrians standing firm in ranks three deep, and presenting an unbroken front of bayonets. Latour Maubourg, who was present, then sent for his personal escort which consisted of half a squadron of Lancers, and having placed these at the head of the column, sent the mass forward. The lancers speared the front rank of the Austrian infantry, and then the squares were practically annihilated!

"Murat himself...led a brigade of Cuirassiers and Carabiniers, against one of the squares of General Metzko's division...broke through. Indeed, the guns and the pistols of the Cuirassiers were the only available firearms...."

Then page 96:

"Eventually the six Austrian divisions on the left flank, separated from the Centre by the Weisseritz stream, and the Plauen ravine; assaulted in front by Victor's Corps, and attacked in the rear by Murat's Cavalry, were utterly routed. By 2p.m. Murat had killed or wounded between 4,000 and 5,000, and had captured 12,000 men. The cavalry then moved in pursuit, and the next day took many more prisoners and guns; the total loss, which fell principally on the Austrians, being 22,000 casualties, 18,000 prisoners, 26guns, and 18 stands of Colours."

Then page 97:

"The success of untrained French cavalry . . . was due to the rain having rendered firearms temporarily useless. "

Similar accounts on the French cavalry's performance during the Battle of Dresdenare given by Petre in Napoleon's Last Campaign in Germany.

This battle offers a dramatic example of what cavalry could do to infantry if their muskets were rendered useless by steady rain (the Katzbach is another example from 1813, fought on the same day as Dresden, this time with the Prussian cavalry taking advantage of the soaked French infantry). Note that the rain did not prevent artillery from firing, and lancers, obviously because of their long weapons, were particularly efficient against the shorter reach of the infantry's bayonets.

Footnotes:

1. The pistols had been shielded from the rain in the wallets and were practically the only firearms able to fire.

2. Possibly the weapon of these riflemen could have been the famous Austrian air rifle, distributed in small numbers in the Austrian army.

Picture: The Saxon Cuirassier Regiment Zastrow breaks an Austrian square at Dresden. Like their allies the French, they were assisted by the rain.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 10

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com