The Essex Committee's Recruitment and Equipping of Dragoons for the Parliamentary Forces of the Eastern Association 1643-44

The Essex Committee's Recruitment and Equipping of Dragoons for the Parliamentary Forces of the Eastern Association 1643-44

When Lieutenant Colonel John Lilburne first inspected the Earl of Manchester's Dragoons in May 1644, he would probably have found that most of the men in his new command spoke with Essex accents. The task of raising a force of dragoons for

Parliament's Eastern Association army had fallen largely on that county in the summer of 1643. Much of the administrative paperwork engendered by the operation has survived, preserving the names and origins of hundreds of ordinary soldiers as well as their officers.

By the end of the first year of war Essex had already supplied 2,000 or more men to the Parliament cause, volunteers for the army of the Earl of Essex. The escalation of the conflict soon necessitated many more troops. In 1643, not only were more men needed to replace casualties and deserters from the Earl's army, but the establishment of the Eastern Association required some 20,000 souls from the eastern counties.

Essex's initial contribution to the Eastern Association infantry alone was expected to be at least another 1,000 men. In contrast to 1642, enthusiasm for the war had dwindled and volunteers were now scarce. The country authorities were therefore forced to introduce conscription in

order to meet their commitments to the new army. At the same time as this highly unpopular operation was being carried out, Parliament

passed an additional Ordinance ordering Essex to raise 1,000 dragoons.

Although the Ordinance came into effect on 12 August 1643, the documentary evidence indicates that the Essex authorities had already begun recruiting some days earlier. Surviving lists from the various parishes of Essex show that at least 289 named men enlisted as dragoons on 3 August

1643. By far the largest contingent of these (60) came from the town of Colchester. As only one dragoon is recorded from the neighbouring hundred of Tendring, it is possible that villagers may also have gone to enlist in town.

A further list of 12 August records the names of 57 dragoons entered on full pay. Over half of these men, such as Nathaniel Newman of Colchester, also appear on the earlier lists of 3 August, suggesting that they were now being organised into companies. Three dragoon companies in particular now began to figure repeatedly in the expense accounts of the Essex Committee, commanded by Captains Holcroft, Harbottle and Miller. The allocation of dragoon horses to other captains, however, prove that more dragoon units existed, some of whom appear to have been attached to locally-raised cavalry units, such as that of Captain Nathaniel Rich.

As with the cavalry, it is clear that the Parliamentary authorities much preferred their dragoons to be volunteers rather than conscripts. One obvious reason must have been that it would be folly to press an unwilling man into military service, and then give him a horse on which he could make his escape. However, both Royalists and Parliamentarians found it easier to attract volunteers for the mounted arms (dragoons and cavalry) than for the infantry. Dragoons, like the cavalry, appear to have come from the middling sort (such as tenant farmers or craftsmen) rather than the labouring poor or the unemployed. Certainly, it is noticeable that whereas infantry conscripts were shamefully neglected by the Essex authorities, the Parliamentary County Committee lavished significant amounts of money on clothing and equipping their dragoons. The dra goons themselves seem to have shared the cavalry's disdain for footsloggers, a fact clearly exploited by the Essex authorities, who used a contingent of their newly-raised dragoons to herd hapless infantry conscripts up to Cambridge.

Equipment

Equipment for the dragoon companies of Holcroft, Harbottle and Miller arrived remarkably quickly. On 16 August 1643, the Committee's treasurer was instructed to forward f 184 15s in part payment for a consignment of snaphaunce pistols and "360 musquets with ring nails & swevells". A later entry records a further instalment of £ 342 for the "360 musketts furnished for Dragoones ... these delivered to Capt. Holcroft, Capt. Harebottle & Capt. Miller". The treasurer was also instructed to pay £ 133 7s for 381 swords "at 7s a piece", to be delivered to the same three captains. Finally, he paid £ 9 for "3 colours & 6 drummes for the severall companyes of Dragoones under the command- of the Right honorable the Earle of Manchester". Frustratingly, there is no indication as to the appearance of these colours. A further order concerned the supply of "great" saddles and "pad" saddles (the former presumably for the use of officers, the latter for issue to the dragoons).

Records of the actual pay given to these three companies have not as yet come to light, although 73 dragoons under the command of two other Essex officers, Captain Carew Mildmay and Captain William Harlackenden, were paid £ 27 7s 6d on 24 August 1643.

The supply of the dragoon's clothing appears to have taken slightly more time to organise, for it is not until 26 January 1644 that Committee accounts recorded Paid to Mr. Will Gray, Merc[han]t Taylor of London in p[ar]t for 1,000 soldiers coates £ 200". These may, of course, have been for the Essex conscripts then enduring winter conditions with the Eastern Association army in Lincolnshire. However, there had been little response to the Eastern Association's continual complaints at the lack of clothes for the Essex infantry, as William Harlackenden, by then the Earl of Manchester's Commissary-General, observed: "the poor soldiers long for coats and the time of year calls for them". The pattern of previous Essex Committee expenditure suggests that it was the dragoons who received William Gray's coats.

The mounting of dragoons is a subject which is subject to considerable debate, particularly the misleading impression given by many writers that dragoon horses were old, broken-down or infirm. Dragoon horses were probably "inferior" to cavalry mounts in that they were simply lighter beasts, unsuitable for carrying cuirassier or harquebusier on campaign. Light horses appear to have been somewhat of a speciality of north Essex, which had previously supplied this type of mount for Queen Elizabeth's expeditions. This may have been one reason why the Parliamentary Ordinance of 12 August 1643 had detailed Essex to raise 1,000 dragoons in preference to other counties. At the same time as men were being recruited, the various Hundreds of Essex were donating suitable horses to carry them. Eventually 679 horses were collected. These were complemented by Committee purchases and individual contributions to bring the final tally of mounts to 942. 881 "Dragoon horses" were distributed amongst various Essex commanders. Captains Harbottle, Holcroft and Miller received 130 each, which, allowing for remounts, suggests that their companies had an establishment strength of 100 men. Other sizeable allocations were given to Captain Dingley (103), Captain Sparrow (100) and Captain Stradley (119).

Suitably mounted and equipped, the various companies of Essex dragoons rode away to war. Hopefully, following further research, their subsequent activities will form the basis of a future article. War certainly took its toll on them, for the companies were described as being in a bad state when the Earl of Manchester's dragoons were reorganised into five companies under the command of Lt. Col. John Lilburne in April-May 1644. Only two of the eight dragoon captains were retained, although this may have been a reflection of their politics rather than their competence. Most of their replacements, such as Richard Beaumont, were radical Independents. Captain St. John Holcroft was one of those forcibly retired. However, many of his men served on. Nathaniel Newman and Edward Robinson, who had enlisted in Essex on 3 August 1643, were named in Richard Beaumont's company of Lilburne's Dragoons during a muster of the regiment held on 16 January 1645. Similarly, Sergeant John Clarke and John Harkyn of Captain Abbott's company may be the dragoons of the same names who enlisted in Essex. When Lilburne resigned his commission rather than take the Covenant in April 1645, his regiment was taken over by Colonel Okey. One of the two dragoons chosen to represent Okey's rank and file during the debates of 1647 was William Hall, perhaps the same William Hall who enlisted as a dragoon in Braintree, Essex, four years before.

Essex's contribution to the Parliamentary war effort was substantial in both men and materiel. When the soldiers eventually returned home, many were maimed and unable to follow their civilian trades. Of the original dragoons, Daniel Wright (lacking a leg) certainly received a small pension, whilst other maimed pensioners whose names coincide with names of original Essex dragoons or John Lilburne's regimental paylists are Thomas Sutton, Henry Lyman and William Burnham. These men and their comrades had come forward to volunteer for Parliament in the peaceful surroundings of their Essex parishes, most with no prior experience of the full horrors of war. By the end of the Civil Wars, inspired by such charismatic leaders as Lilburne and Okey, and seasoned by campaigns such as Marston Moor and Naseby, they had proved to be some of the best troops in Parliament's service.

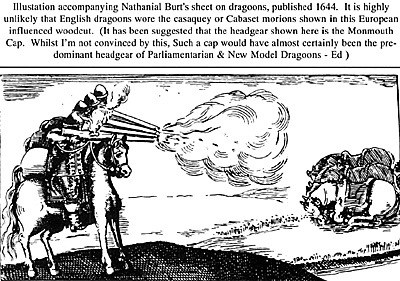

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Illustation accompanying Nathanial Burt's sheet on dragoons, published 1644. It is highly unlikely that English dragoons wore the casaquey or Cabaset morions shown in this European influenced woodcut. (It has been suggested that the headgear shown here is the Monmouth Cap. Whilst I'm not convinced by this, Such a cap would have almost certainly been the pre dominant headgear of Parliamentarian & New Model Dragoons - Ed )

Illustation accompanying Nathanial Burt's sheet on dragoons, published 1644. It is highly unlikely that English dragoons wore the casaquey or Cabaset morions shown in this European influenced woodcut. (It has been suggested that the headgear shown here is the Monmouth Cap. Whilst I'm not convinced by this, Such a cap would have almost certainly been the pre dominant headgear of Parliamentarian & New Model Dragoons - Ed )

Back to English Civil War Times No. 56 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com