CH Firth, one of the greatest English Civil War scholars, presented this paper exactly 100 years ago. We have made minor adjustments to make it more readable for the early 21st Century researcher. The copious footnotes will appear as the final part of this classic and influential article.

The nucleus of Cromwell's regiment was the troop of horse which he raised at the beginning of the Civil War. In the list of the army under the Earl of Essex in 1642 there are 75 troops of horse, and the 67th troop is that of Oliver Cromwell. It must not, be supposed that the troops enumerated in this list were raised entirely at the expense of the persons commanding them though no doubt some few of them were. Cromwell was not rich, and like other leading Parliamentarians, he had subscribed liberally to the loan for raising Essex's army. He contributed £ 500 for that purpose, which was probably not much less than a year's income.[2]

From the fund obtained by these subscriptions and from loans procured in London the Parliament defrayed the cost of equipping its troops. A captain who was given a commission to raise a troop of horse received a certain sum from the Treasury to enable him to mount and arm his troopers and his subordinate officers. This sum was called mounting money,' and Cromwell's name appears in a list of 80 captains who were each of them paid the sum of £ 1,041 for this purpose.[3]

Cromwell's officers consisted of Lieutenant Cuthbert Baildon, Cornet Joseph Waterhouse, and Quartermaster John Desborough, and his men were probably volunteers enlisted in Huntingdonshire and Cambridge.[4]

The business of raising the troop was completed in August 1642, and in September it was ready to take the field. The first notice of it to be found in the accounts is a payment dated September 7, 1642, for a month's pay due to Captain Oliver Cromwell's troop of 60 men, mustered on August 29, and the receipt is signed by John Desborough. A week later, on September 13, 1642, ' the Committee appointed to settle the affairs of the kingdom ' ordered that Captain Cromwell and two other officers named ' should forthwith muster their troops of horse, and make themselves ready to go to his Excellency the Earl of Essex,' who had set out three days before for the headquarters of his army at Northampton.[5] Cromwell accordingly joined Essex, and his troop was put into the Lord General's own regiment of horse, under the command of Sir Philip Stapleton. Under Stapleton's command Cromwell and his troop fought at Edgehill, though there is some evidence that Cromwell was not on the field at the time when the battle begun, but arrived later.[6]

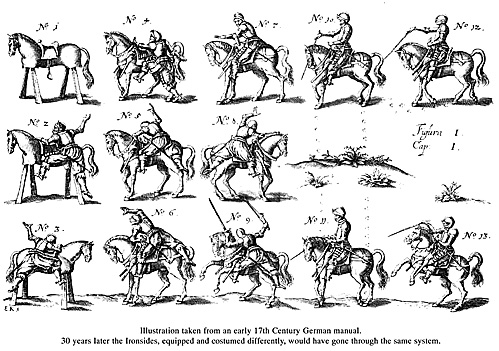

After Edgehill Essex retreated to Warwick, but about the beginning of November his army was quartered about London. The next notice of Cromwells troop is a warrant from Essex, dated December 17, 1642, for a fortnights pay to Captain Cromwell's troop. In it Cromwell is described as Captain of a troop of 80 harquebusiers.[7] the meaning and use of the term harquebusiers are explained in a later part of this paper; at present it is enough to say that harquebusiers were a class of cavalry less heavily armed than cuirassiers. The fact that Cromwell's troop of 60 had now become a troop of 80 is also worth noting, though it is not easy to explain.[8]

Less than a month later, Cromwell left the army under Essex to return to the eastern counties. At the close of 1642 the need of united action for defensive purposes led to the formation of little local leagues amongst the counties supporting the Parliament. On December 22, 1642, the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, and Cambridge established what was known as the Eastern Association. On January 16, 1643, eight midland counties, including Huntingdonshire, formed a similar association, but, unlike the former, it soon broke up.

Cromwell, as member for Cambridge, was appointed one of the committee for that county, and being a person of influence in Huntingdonshire, was one of its committee also. In both capacities, therefore, he was wanted in the eastern counties, and obtained leave from Essex to repair thither, and to take his troop with him, as soon as the first campaign was over. There Cromwell hoped to carry out the scheme which he had discussed to Hampden - to raise men that had a spirit that would do something in the work, a spirit that was likely to go on as far as gentlemen would go - such men as had the fear of God before them and made some conscience of what they did. [9]

With this object before him he set out from London about the beginning of January 1643. On his way down, about January 14, he seized the Royalist high sheriff of Hertfordshire, as he was proclaiming the King's Commission of Array at St. Albans, and sent him up to London to answer for his conduct to Parliament.[10]

On January 23 or thereabouts, he was at Huntingdon, and three or four days later at Cambridge.[111 Cromwell brought his commission to raise a regiment in his pocket. He is described as colonel in the proceedings of the Norfolk Committee on January 26, 1643, [12] and in a letter written by Lord Grey on February 6, though it is not till March that he is mentioned as a colonel in the newspapers. His commission was probably not derived from Essex, but from Lord Grey. William Lord Grey of Wark had been chosen Commander-in Chief of all the forces to be raised in the Eastern Association, with the rank of major-general, and Essex had been desired to grant him a commission empowering him to appoint colonels, captains, and other officers. It was from Lord Grey, therefore, that Cromwell's commission as colonel was probably derived. [13]

As soon as he was established at Cambridge, Cromwell set to work to convert his troop into a regiment. The principle upon which he selected his officers and enlisted his men was that set forth in his conversation with Hampden. He had already put it into practice in the formation of his original troop. 'At his first entrance into the wars.' writes Baxter, ' being but a captain of horse he had special care to get religious men into his troop. These men were of greater understanding than common soldiers, and therefore more apprehensive of the importance and consequence of war; and making not money but that which they took for the public felicity to be their end, they were the more engaged to be valiant; for he that maketh money his end doth esteem his life above his pay, and there-ore is like enough to save it, when danger comes, if possibly he can: but he that taketh the felicity of Church and State to be his end, esteemeth it above his life, and therefore will the sooner lay down his life for it. And men of parts and understanding know how to manage their business, and know that flying is the surest way to death, and that standing to it is the likeliest way to escape; there being many usually that fall in flight for one that falls in valiant fight. These things 'tis probable

Cromwell understood; and that none would be such engaged valiant men as the religious. But yet I conjecture, that at his first choosing such men into his troop, it was the very esteem and love of religious men that principally moved him; and the avoiding of those disorders, mutinies, plunderings, and grievances of the country, which deboist men in armies are commonly guilty of. By this means he indeed sped better than he expected. Aires, Desborough, Berry, Evanson, and the rest of that troop did prove so valiant, that as far as I could learn they never once ran away before an enemy.'[14]

Whitelocke briefly confirms Baxter's statement, describing the regiment as 'most of them freeholders and freeholders' sons, and who upon matter of conscience engaged in this quarrel and under Cromwell. And thus being well armed within, by the satisfaction of their consciences, and without by good iron arms, they would as one man stand firmly and charge desperately.' [15]

Cromwell's opponents amongst his own party complained bitterly of the method in which he selected his officers. 'Col. Cromwell raysing of his regiment,' wrote one of them in 1645, ' makes choyce of his officers, not such as weare souldiers or men of estate, but such as were common men, pore and of mean parentage, onely he would give them the title of godly pretious men.... I have heard him oftentimes say that it must not be souldiers nor Scots that must doe this worke, but it must be the godly to this purpose.... If you looke upon his own regiment of horse see what a swarme ther is of thos that call themselves the godly; some of them profess they have sene visions and had revelations.'

But in spite of the fact that Cromwell's officers were most of them men of no great local position, and that his'men were selected with far more care than was usual, the develop,ment of his troop into a regiment was astonishingly rapid. In March 1643, when Cromwell suppressed the intended Royalist rising at Lowestoft, he had with him, according to a contemporary letter, 'his five troops.' [16]

In September, when Lincolnshire was added to the Eastern Association, the ordinance authorising the addition states that 'Colonel Cromwell hath ten troops of horse already armed, which were heretofore raised in the said Associated Counties.' [17] Baxter states that Cromwell's regiment became in the end ' a double regiment of fourteen full troops, and all these as full of religious men as he could get. [18]

Baxter's statement has been called in question, on the ground that six troops was the usual number in a regiment,[19] but the fact that Cromwell's regiment did actually contain fourteen troops is proved by the existence of a pay,-roll for Manchester's army showing the sums paid by his treasurer, Gregory Gawsell, to different troops and companies between April 29, 1644, and March 1, 1645.[20] Taking this list as a basis it is possible to show who the commanders of these fourteen troops were and when they were raised.

The term ' Ironsides ' was a nickname, originally conferred upon Cromwell by Prince Rupert, which was afterwards applied to the regiment, as well as to the man who commanded it. Popular usage has come to employ it as a designation for Cromwell's troopers rather than for Cromwell himself, and in its popular sense it is employed in the title of this paper. [1] In this paper, therefore, I shall attempt to trace the history of Cromwell's regiment of horse from its origin in 1643 to its incorporation in the New Model in 1645 and to show how it was raised, equipped, and organised, and by whom it was commanded.

The term ' Ironsides ' was a nickname, originally conferred upon Cromwell by Prince Rupert, which was afterwards applied to the regiment, as well as to the man who commanded it. Popular usage has come to employ it as a designation for Cromwell's troopers rather than for Cromwell himself, and in its popular sense it is employed in the title of this paper. [1] In this paper, therefore, I shall attempt to trace the history of Cromwell's regiment of horse from its origin in 1643 to its incorporation in the New Model in 1645 and to show how it was raised, equipped, and organised, and by whom it was commanded.

The 14 Troops and Their Officers

Back to English Civil War Times No. 56 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com