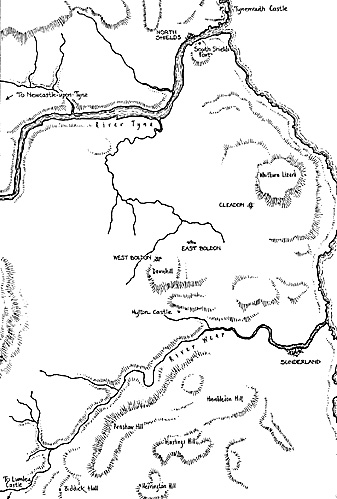

At the beginning of March 1644 the Scots army crossed the Tyne, by-passing Royalist held Newcastle and made for Sunderland. This move led to nearly a month of fighting and a largely unknown major battle.

Leven entered the town on the 4th of March. The inhabitants immediately took the opportunity to declare for Parliament and he was thus able to threaten the Royalist line of communications while at the same time drawing his own supplies through the port. The natural consequence of this move was that the Marquis of Newcastle now had to fall back southwards. On the 6th of March he crossed the River Wear by the New Bridge below Lumley Castle and came in sight of a Scots cavalry outpost on Penshaw Hill. After some skirmishing the Scots fell back and next day both armies drew up in order of battle.

By this time the Scots were established on Humbledon Hill just to the south-west of the town and Newcastle's army was probably on Hastings Hill a little to the east of Penshaw. [1] Heavy snowfalls prevented any movement during the morning but there was some skirmishing in the afternoon as both sides tried too feel their way forward. It quickly transpired that this was no place to fight a battle for it was heavily enclosed with banks and hedges and the Scots moreover had part of their front covered by a stream called the Barnes Bum running through a dene or narrow valley. Both armies therefore faced each other until nightfall when the Royalists retired to Penshaw.

For a time the skirmishing escalated and the Scots cavalry received the support of some commanded musketeers. Then the weather closed in again and the Royalists safely retired to Durham, having accomplished nothing but the loss of a considerable number of horses to the bad weather and consequent shortage of forage. These were losses which Newcastle could ill afford. Leven tried to follow up his advantage by advancing towards Durham on the 12th but Newcastle failed to oblige him with a battle. As there was no forage to be found for his cavalry he in turn retired back to Sunderland on the l3th and tried to take steps to improve his supply position. Since neither food nor forage could be obtained locally he was totally dependent on the provisions being shipped in through the port. Unfortunately the same bad weather which hampered military operations was also causing havoc at sea.

Consequently Leven now turned his eyes northwards. On the 15th an unsuccessful attempt was made to storm one of the Royalist forts covering the mouth of the Tyne, at South Shields. Undismayed, the Scots made a second and this time successful attempt on the 20th. Royalist morale was not improved when Lieutenant Colonel Ballentyne of Leven's Horse beat up some Royalist cavalry at Chester-le-Street on the same day. Stirred into action the Marquis once again drew his army out of Durham on the 23rd and moved forward to offer battle for a second time. On this occasion he moved along the north bank of the Wear, perhaps hoping to force the Scots to relinquish the fort at South Shields.

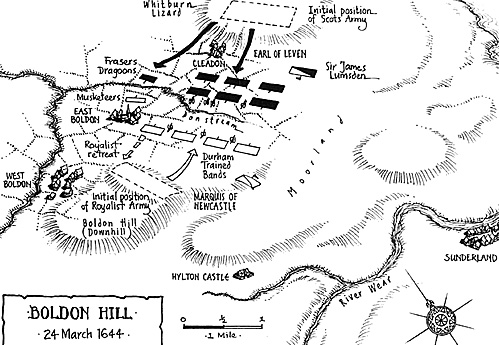

Leven very quickly got the bulk of his own army across the river and on Sunday the 24th of March both took up their positions facing each other about three miles apart. The Marquis drew up his army on the imposing Boldon Hill (now known as Down Hill) facing northeastwards to the Scots on the only slightly lower Whitburn Lizard. Between them lay a flat expanse of moorland cut across by the valley of a stream called the Don and interspersed with hedged enclosures around the villages of West Boldon, East Boldon and Cleadon. The latter played no part in the battle but the two former lie at the foot of Down Hill [3] It was not particularly suitable ground for cavalry to operate upon and the fight which followed was very largely an infantry battle.

With the aid of some local keelmen (boatmen employed in transporting coal) Leven's General of Artillery, Sandie Hamilton managed to get one of his big guns across the Wear, together with a number of smaller ones, but in the process two other large pieces were lost in the river . [4] For most of the day both sides then contented themselves with a fairly ineffectual cannonade. Neither side was keen to launch a frontal attack. The Marquis had came north with some 5,000 foot and although many of those raised by Glenham were perforce left as a garrison for Newcastle, he had also been joined by some of the Durham Trained Bands. Even allowing for the inevitable heavy wastage attendant on a winter campaign he still ought to have been able to bring about 5-6,000 men into the field.

The Scots were in a similar situation. Leven had crossed the border with around 10,000 infantry in January but close on 3,000 men were left behind at Heddon to mask Newcastle. Sir James Lumsden brought some or all of the cavalry left there across on the 23rd, but nevertheless by the time smaller detachments and wastage are taken into account, his total field force cannot have outnumbered that of the Royalists.

Once driven out of East Boldon, Newcastle's men retreated up the slopes of Down Hill. They were not followed in the darkness and at some point during the early hours of the following morning the Scots broke contact and fell back to their main position on Whitburn Lizard. Although the Mercurius Aulicus report made the most of this, it also had to admit to the loss of some 240 men. In any case the Marquis began drawing off his army on the 25th and covered once again by Sir Charles Lucas he retired to Durham on the 26th. While the battle tends to be dismissed as a minor skirmish the true scale of the affair is evident both from the 240 Cavalier dead and the 37 barrels of powder which the Scots expended in killing them.

Five days later, after re-equipping his regiments Leven broke up his camp at Sunderland and moved southwards to Easington. There he was able to find sufficient forage for his cavalry and still maintain contact with the Royalists. On the 8th of April the weather at last began to improve and he decided to increase the pressure. Moving south-west on to the Quarrington Hills he took up a position threatening the Royalist line of ommunications a mile or two south of Durham. Newcastle's position was once again untenable. Faced with the choice of fighting or falling back he opted for retreat.

[1] A Faithfull Relation of the late Occurrences and Proceedings of the Scottish Army before Newcastle. IN Terry, C.S. 'The Scottish Campaign in Northumberland and Durham' Archaeologia Aeliana (New Series) Vol.XXI (1899) p162-31bi and Firth, Memoirs of the Duke of Newcastle p201-2 (Newcastle's account) The location of the fighting on the 6th can be worked out, with a little application, from both the accounts above and the Duchess's reference (Firth p35) to 'Pensher Hill'. As to the position occupied by the Scots on the 7th there is an unambiguous reference in the ordnance papers to 30 axes being issued to the army while it was at 'Hamelton' Hill. Newcastle also describes the Scots as standing on a 'plain' behind the valley and oddly enough there is in fact a Plains Farm in what would have been the Scots rear area on Humbledon Hill. For some reason and despite the fact that it undoubtedly took place on the south side of the River Wear, historians also tend to have some difficulty in distinguishing this engagement from the later one at Boldon on the north side of the river.

[2] Firth Memoirs p203

[3] Once again it is relatively straightforward to identify the site of this battle using the available texts. All too often historians casually refer to it as 'Bowden' Hill without troubling themselves to take the rather obvious step of looking at a map. Others prefer to call it the battle of Hylton. This again can be misleading as Hylton Castle actually lies between the southern slopes of Down Hill and the River Wear. No fighting took place on this side of the hill but the now vanished Jacobean mansion which stood there in 1644 was the home of one of Newcastle's officers Colonel John Hilton - and the Marquis may well have slept there or even used it as his headquarters. One source does rather confusingly refer to the fighting taking place at West Bedwich (Biddick), but this lies on the other side of the river and it is clear from the context that West Boldon is intended.

[4] The Scots ordnance papers record two guns (weight unspecified) 'broken' at Boldon Hill. One of them was dredged from the bottom of the river in the 19thC.

[5] All six of the Scots regiments can be identified from the ammunition records in the Ordnance papers. In addition, when the army's equipment deficiencies were made good on the 29th all six (uniquely) received pikes presumably to replace those, lost of broken in the fighting at Boldon - the numbers appended to each unit refer to the number of pikes issued to each.

[6] A True Relation of the Proceedings of the Scottish Army from the 12 of March instant to 25.

Encouraged the Scots pushed forward again on the 8th at which the Royalists set fire to their quarters and drew off, covered by some horse [2]:

Encouraged the Scots pushed forward again on the 8th at which the Royalists set fire to their quarters and drew off, covered by some horse [2]:

we sent off 120 horses to entertain them near their own leaguer, Sir Charles Luca his major (Sir Simon Fanshaw) commanding them. when meeting with 20' of the enemy's the first that charged them not passing 60 of this one regiment. Notwithstanding the enemy was so placed before a hedge, where they had some dragooners as it seems. they were confident ours would not have come up unto them; but when they saw that their muskets could not prevent the courage of our men, they turned their backs and leaped over their dragooners, affording our men the execution of them to a great body of theirs, in which chase our men killed some 40 of them, and had taken near 100 men, but they advanced so suddenly we could bring off but 20 of them. of whom there were three English - one of them were hanged immediately, having formerly served in our army: their lancers did seem to follow eagerly upon our men in their retreat in great numbers, but we had not passing six men hurt, whereof one died...

Of five ships sent from Scotland at the beginning of March three were lost and two driven to take shelter in the Tyne. Both of the latter were of course seized by the Royalists.

Of five ships sent from Scotland at the beginning of March three were lost and two driven to take shelter in the Tyne. Both of the latter were of course seized by the Royalists.

Late in the afternoon Fraser's Dragoons opened the battle with an attack on some Royalist musketeers lining the hedges around East Boldon. The fight quickly escalated and according to the Royalist account in Mercurius Aulicus four of Newcastle's Regiments were engaged by six Scots ones. [5] Once begun the fighting continued through the night [6]:

Late in the afternoon Fraser's Dragoons opened the battle with an attack on some Royalist musketeers lining the hedges around East Boldon. The fight quickly escalated and according to the Royalist account in Mercurius Aulicus four of Newcastle's Regiments were engaged by six Scots ones. [5] Once begun the fighting continued through the night [6]:

After the Armies had faced each other most part of that day, toward five oclock the Cannon began to play, which they bestowed freely though to little purpose, and withall the commanded Foot fell to it to drive one another from their hedges, and continued shooting till eleven at night. in which time we gained some ground, some barrels of gunpowder, and ball and match. wee lost few men, had more hurt and wounded of whom no Officcr of note hurt with danger but the Lieutenant Colonel of the Lord Lothian's Regiment; (Patrick Leslie) what their loss was is yet uncertain to us, but we know they had more slain. as wee finde finde being masters of their ground.

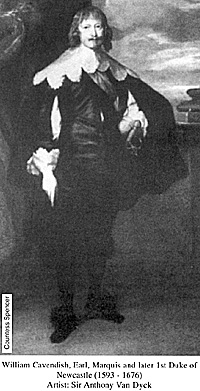

William Cavendish, Earl, Marquis and later 1st Duke of Newcastle (1593 - 1676) Artist: Sir Anthony Van Dyck

William Cavendish, Earl, Marquis and later 1st Duke of Newcastle (1593 - 1676) Artist: Sir Anthony Van Dyck

Footnotes

General of the Artillery's Regt. (Hamilton's) 36

Lord Chancellor's Regt. (Loudoun's) 24

Earl of Lindsay's Regt. 25

Lord Livingston's Regt. 30

Earl of Lothian's Regt. 40

Master of Yester's Regt. 20Map

Back to English Civil War Times No. 56 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com