Skippon's reputation ensured that he was appointed as Sergeant-Major General for the New Model Army under Sir Thomas Fairfax. He began his work by putting into effect the reorganisation of the three armies of the Earl of Essex, Sir William Waller and the Eastern Association into one, the New Model Army.

At right: Contemporary engraving of Philip Skippon as Sergeant-Major General of the New Model Army. (Author's collection).

This involved the disbanding of several regiments; and while the private soldiers were needed for the new army, not all the officers were, and many units were in a state bordering upon mutiny. Skippon resolved the unrest by drawing the soldiers together and doing some plain talking. He began by reminding them of their loyalties:

'Gentlemen and fellow-soldiers all, I am now to acquaint you with the commands of Parliament, to which in con science to God, and love to our country, we are bound to give all cheerful and ready obedience. There is a necessity lies upon us (since three armies are to be reduced into one) that some commanders and officers must go out of their employments wherein they now are; it is not out of any personal disrespect to any of you that shall go of, and therefore I hope you Will behave yourselves accordingly'. He continued with the even plainer warning :'let no man deceive himself; for although he may perhaps occasion some trouble in the present business, yet in the issue the greatest mischief will fall upon himself'.

Skippon succeeded where others might well have failed, and the creation of the New as a fighting force from the remnants of three others owes more to him than to either Fairfax or Cromwell.

This new army consisted of 12 infantry regiments organised in three brigades; I I cavalry regiments; a regiment of dragoons (mounted infantry), and an artillery train. Its theoretical establishment of 600 men plus officers for cavalry regiments and 1,200 men plus officers for infantry regiments gave the New Model Army a ratio of nearly one cavalryman to every two infantrymen. According to contemporary tactical doctrines this was the optimum ratio for an army which was to campaign with a view to forcing battle in open country. The number of infantry regiments was considered to be the optimum for an army, which was to fight as a single force. Evidently, this army was designed according to contemporary military theory with one aim in mind: the destruction of the best of the surviving Royalist armies, the Mug's Oxford Army.

NASEBY, 1645

When the two forces met at Naseby on 14 June 1645, the New Model's commander, Sir Thomas Fairfax, left the deployment of the Parliamentary infantry to Skippon while Oliver Cromwell, as Lieutenant General of the Horse, deployed the cavalry. Skippon drew up his infantry regiments in a simple style, which he had learned while serving in the Dutch army. This contrasted with the more complex deployment of the Royalist army, which followed the practice of German armies during the Thirty Years' War. Skippon's simpler formation proved more robust.

Although the first line of Parliamentary infantry regiments was broken by the Royalist attack, Skippon's reserves in the second line followed his instructions and advanced to sweep away the Royalist infantry before they could regroup. Once again Skippon fought in the front lines with his infantry, receiving a wound in his right side from a musket bullet at close range which burst through his armour and passed entirely through his body.

Despite the agony of his wound Skippon stayed in the saddle for two and a half-hours, until his infantry had rallied from their early reverse and overthrown their Royalist opponents. One of his officers, George Bishop, helped him from the battlefield to a nearby house where his wound was dressed, and remarked: I'Sir, your wound hath caused a little cloud on this glorious day'. Skippon replied: 'By no means let mine eclipse its glory, for it is to my honour that I should have received a wound'.

The Speakers of both Houses of Parliament sent letters of thanks to Skippon and, more practically, sent Dr. Clarke from London to tend his wound. He had completed his convalescence by December 1645, and was appointed Governor of the city of Bristol; but left to join the main army and to direct siege operations against Oxford in May 1646. Oxford surrendered on terms in June before an assault could be mounted. In December that year Skippon commenced his Parliamentary career and was returned as MP for Barnstable. He was also entrusted with command of the treasure convoy of £ 200,000 sent from London to Newcastle as payment of the price the Scots demanded for the surrender of King Charles. Skippon remained at Newcastle with his own regiment, and the king was taken south to Holmby House.

Skippon was not involved in the early stages of the mutiny of the New Model Army, but he was too prominent a military leader to be left alone. A group of Presbyterian MPs led by Denzil Holles hoped to use Skippon's standing in the army to persuade some of the soldiers to volunteer for service in Ireland and the rest to disband peacefully on worthless promises of settlement of their arrears of pay. Skippon had managed to prevent mutiny on the formation of the New Model, and Holles' group hoped that by appointing him as commander of a new army for service in Ireland he could resolve their difficulties. Skippon was reluctant to accept this appointment, but was prevailed upon to do so, only because he was persuaded it was essential for the good of the state.

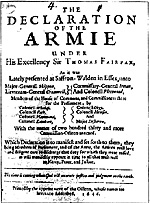

'The Decleration of the Armie', the famous pamphlet printed at the direction of representitives of the mutinous New Model Army to show the basis of their dispute with their Parliamentary masters. Skippon was appointed one of the Parliamentary commisioners to negotiate with the army.(Author's collection)

'The Decleration of the Armie', the famous pamphlet printed at the direction of representitives of the mutinous New Model Army to show the basis of their dispute with their Parliamentary masters. Skippon was appointed one of the Parliamentary commisioners to negotiate with the army.(Author's collection)

Declaration of Army Large (slow: 97K)

THE ARMY MUTINY

Skippon's appointment was now overtaken by events, how ever, as the temper of the army grew steadily more mutinous. Three delegates or 'agitators' from the cavalry - Edward Sexby, William Allen and Thomas Shepherd - brought him a letter signed by themselves and 13 others which expressed their complaints, and sought his aid as one I that hath so often been engaged with us, and from that heart that hath as often been so tender over us'. Skippon, an MP himself; read the letter in the House of Commons the following day, to the fury of the Presbyterian party led by Holles.

The soldiers were questioned in the Commons, but their testimony only showed the length of their service in the Parliament cause: all claimed to have served since the battle of Edgehill, and their declared determination to receive some just settlement. One recalled that Skippon had found him lying wounded after the battle of Newbury, and left him five shillings (over a week's pay for a soldier) to support himself while he recovered, a shilling for each wound. Skippon recalled the incident, and although he did not agree with their making demands of Parliament he had some sympathy with the men themselves. He spoke up for the army delegates during the debate, saying that 'they were honest men, and he wished they might not be severely dealt with'.

It was now apparent that serious steps must be taken to deal with the mutiny, and Skippon was appointed as Parliament's chief commissioner to discuss terms with the army; the other commissioners were Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton and Charles Fleetwood. This placed Skippon in an invidious position, as although he felt a strong loyalty to Parliament and the good of the country as a whole he also sympathised with the soldiers' complaints. He had personal experience of the privation caused by arrears of pay from his service in European armies, and must have felt that the settlement offered by Parliament was a callous return for his soldiers' efforts on their behalf.

Even so, he might have been able to use the great personal influence which he retained over the common soldiers to bring about a settlement if only Parliament had been prepared to offer reasonable terms. Without acceptable terms as a viable bargaining counter Skippon was caught in the middle of an insoluble argument; and as a result his influence was 'quite lost in the army by endeavouring to please both sides'.

When the army seized the king as a bargaining counter on 4 June 1647, Skippon formally advised Parliament that they had no option but to accede to the soldiers' demand for their arrears of pay, as they now faced armed revolt. Finally appreciating the gravity of their situation, Parliament voted the army its arrears; but it was now too late, as the mutiny had developed political overtones and this belated promise was no longer enough. Writing after the event, Holles considered that 'by this unfortunate man's (Skippon's) interposition at that time... all was dashed'; but Holles had miscalculated the depth of the army's discontent from the beginning, and Skippon's estimate of the position was entirely accurate.

Philip Skippon brought Parliament's latest offer to the army at a major rendezvous at Triploc Heath near Cambridge on 10 June; and although he was met with respect, he heard cries of 'Justice, Justice' when he rode by each regiment instead of the cheers he would have received a year before. Although he continued to negotiate with the army on Parliament's behalf; Skippon no longer had any hopes of reconciliation. In July he wrote to the Speaker of the House of Commons seeking release from his appointments as commander of the proposed army for Ireland and its chief commissioner in negotiations with the army. This marked the end of his attempt at mediation, and he rejoined the army in his old capacity as Sergeant-Major General.

Ensign of Foot. Each company of infantry in a regiment carried it's own fl1ag, both

the flag and the officer who carried it being described as an 'Ensign'. This figure

provides a good illustration of the appearance of junior officers on either side at

Naseby. (Courtesy the Tmstees of the Royal Armouries).

Ensign of Foot. Each company of infantry in a regiment carried it's own fl1ag, both

the flag and the officer who carried it being described as an 'Ensign'. This figure

provides a good illustration of the appearance of junior officers on either side at

Naseby. (Courtesy the Tmstees of the Royal Armouries).

When the army made its triumphal entry into London on 6 August it was led by all three of its old commanders, Sir Thomas Fairfax (Lord General), Philip Skippon (SergeantMajor General) and Oliver Cromwell (Lieutenant General of the Horse).

THE SECOND CIVIL WAR

As negotiations for a political settlement continued, former Parliamentarians joined with Royalists and the Scots to oppose the army in a second civil war. While the army marched north to crush their opponents at the Battle of Preston (17-19 August 1648), London remained the key to the country. Skippon was the man chosen to command the London Trained Bands once again and hold London secure, possibly because he was the only man trusted by the army, the City authorities and the pro-army MPs.

With unrest seething throughout the City Skippon retained control; and when the Royalist Earl of Norwich marched a force to the outskirts of the City and seized Bow Bridge and Stratford, Skippon was able to persuade the Trained Bands to march and oppose it. This was one of the most critical events of the war, as although Norwich had too small a force to take the City if the Trained Bands would oppose him, it was large enough to spark a Royalist rising if the Bands refused to muster. In the face of the London Trained Bands Norwich could only march away tojoin the Royalist forces in Colchester. The main interest of the citizen soldiers of the Militia was in their families and businesses, and in the confusing political climate of the time Skippon was a man they knew and felt they could trust - one certainty in a 'world turned upside down'.

After the Second Civil War Skippon was appointed to the special tribunal which put King Charles on trial for his life but, like Fairfax, he refused to take part in it. He remained a respected Figure for the remainder of his life, Sitting in Cromwell's Parliaments in 1654 and 1656 as MP for King's Lynn,. as a member of the council of State and in December 1657 in the House of Lords. He was also still regarded as the one man who could control London in times of disturbance; and he held it again in 1650 when Cromwell marched North once more to crush the Scots during the Third Civil War, in 1655 during the Royalist John Penruddock's rising, and again in 1659 when 'Tumbledown Dick' Cromwell's brief government fell. He lived to see John Lambert go north to oppose the march of General George Monk's army on London, but died before a new Parliament met to restore the Monarchy.

THE LAST WORD

Throughout his career as Parliamentary soldier Skippon's personal qualities of courage, determination and integrity gained him the respect and loyalty of his soldiers and the admiration of his enemies. His exceptional experience and ability made him the perfect Sergeant-Major General of his day, with the technical competence to visualise an army's battle formations and the practical ability to turn paper plans into reality. A very tough soldier, he was able to continue in command of his infantry at Naseby with a wound which would have killed a lesser man on the spot; but his soldiers' respectful comments also speak of his compassion for their suffering, his fighting alongside them in the front lines and sharing the hardships of their marches. His contemporaries stressed his reliability using terms such as 'stout Skippon' or 'honest Skippon', but perhaps the most revealing summary of this remarkable soldier comes from the epitaph written by his stepdaughter Katherine Phillips, daughter of his second wife. This concludes:

'For his great heart did such a temper show,/Stout as a Rock, yet soft as melting SnowAn him so prudent, and yet so sincere/The Serpent much, the Dove did more appear:/He was above the little Arts of State, And scorn'd to sell his Peace to mend his Fate/Anxious of nothing, but an inward spot, His hand was open, but his conscience not/Just to his Word, to all Religious kind an Duty strict, in Bounty unconfin'd;/And yet so modest was to him less pain/To do great things, than hear them told again.'

Note: I am obliged to Dr. Peter Gaunt, Chairman of the Cromwell Association,for mentioning Katherine Phillips verse to me. This article first appeared in 'Military Illustrated'. Our thanks to the editor Tim Newark for permission to use this article.

More Skippon

Back to English Civil War Times No. 54 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com