Introduction

Few aspects of the military history of the First Civil

War, both at the time and since, have caused more confusion

and controversy than the Royalists' use of troops from

Ireland. Their numbers, effectiveness, impact on the Royalist

cause and even their nationality have been the subject of

much heated debate. This new examination is intended as a

contribution towards a more measured assessment of these

questions - not, I feel sure, as the final word on the subject!

Few aspects of the military history of the First Civil

War, both at the time and since, have caused more confusion

and controversy than the Royalists' use of troops from

Ireland. Their numbers, effectiveness, impact on the Royalist

cause and even their nationality have been the subject of

much heated debate. This new examination is intended as a

contribution towards a more measured assessment of these

questions - not, I feel sure, as the final word on the subject!

The Coming of the "Irish"

By the summer of 1643, despite a continuing run of military successes, the King and his advisers were facing the prospect of the war lasting a considerable time longer. They were, for example, no nearer to capturing London than they had been at the, start of the war, whilst the strongly regional loyalties of many of the Royalist supporters in the North and West, as well as the remaining Parliamentarian garrisons in those areas, were preventing Charles from capitalising on his victories by drawing on his armies there for operations in the decisive Southern England theatre of the war.

Parliament still had considerably superior material resources at its disposal, and an urgent new factor was injected by Pym's negotiations with Scotland, which would lead to the signing of the Solemn League and Covenant, and the arrival in the new year of a Scottish army to fight alongside the Parliamentarians.

In these circumstances, the Royalist leadership was

anxious to obtain help from abroad. Whilst negotiations

continued in the hope of obtaining an alliance with one or

more foreign governments, a more immediate, and indeed

realistic attraction was presented by the various English

troops serving abroad. Prince Rupert had been pressing since

the winter to t to obtain the release of the English regiments in

Holland [1] but still more

attractive was the possibility of obtaining the use of some of

the 20-30,000 troops serving in Ireland. [2]

These were a mixture of the Old Army in Ireland and

the new units which had been despatched from England in

1641/42 to combat the rebellion of the Irish Confederates. All

had by this time gained considerable combat experience, and

were potentially highly valuable. The idea of using them

against the King's opponents in mainland Britain was not, of

course, a new one. Such a suggestion in 1641 had been one of

the reasons for the impeachment and execution of the then

Lord Deputy, Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, but the

notion was now pursued with renewed urgency.

In order to release some of the troops for service in

England , it would be necessary to reach a truce with the Irish

Confederates, who in any case had no reason to welcome the

prospect of a victory by Parliament.

<>The current Lord Deputy, James Butler, Earl of Ormonde,

on the King's instructions began negotiating with the Irish

Confederates early in 1643, Charles writing to him on March

23rd that once peace was made: "Then my lrish army is to

come over with all speed to assist me, and not else unless I send you

word". [3] In fact, a

steady flow of individual officers from the forces in Ireland

had been returning to England since the summer of 1642.

Many of them took service with the King, examples being the

ruthless Sir Michael Woodhouse, who became Colonel of the

Prince of Wales' Regiment of Foot, and later Governor of

Ludlow, and Major John Marrow, with the Royalists by July

of 1643. Others, initially at least, took service with Parliament,

two prominant examples, Sir Faithfull Fortescue and Sir

Richard Grenvile, later deserting to the Royalists.

Thus, from the opening of hostilities, the King was

already receiving valuable military expertise from the

forces in Ireland, and this process took a decisive turn

when, on September 15th, 1643, Ormonde succcessfully

concluded a truce or "Cessation" with the Irish

Confederates. The way was clear to begin transporting the

Irish Army over to England.

The actual results of the Cessation have been the

subject of considerable debate. The main areas of

disagreement lie in how many troops were actually shipped

over, and their nationality. The latter point will be discussed

later, initially I intend to answer the question of numbers. A

leading researcher in the field, Joyce Lee Malcolm, has given a

total of some 22,240-22,740 men, half of them native Irish,

arriving in the period October 1643-June 1644, and this figure

has gained considerably more credence than is warranted.

[4] The table below

gives what I believe to be a more accurate summary of the

forces which the King actually obtained from Ireland.

This figure, whilst considerably lower than Malcolm's,

is still almost certainly too high. The 700 men listed as arriving

at Bristol in February 1644, are almost certainly the product of

Parliamentarian propaganda and misinformation, whilst the

2,000 troops landing at Whitehaven/Carlisle in February 1644,

are mentioned in the Royalist propaganda sheet "Mercurius

Aulicus ", but no other reliable contemporary source. A

real total of about 13,000 (2,000 of them Montrose's "Irish

Brigade" under Alastair MacDonald) may be nearer the mark.

How were the 11,000 or so troops from Ireland which

actually arrived employed?

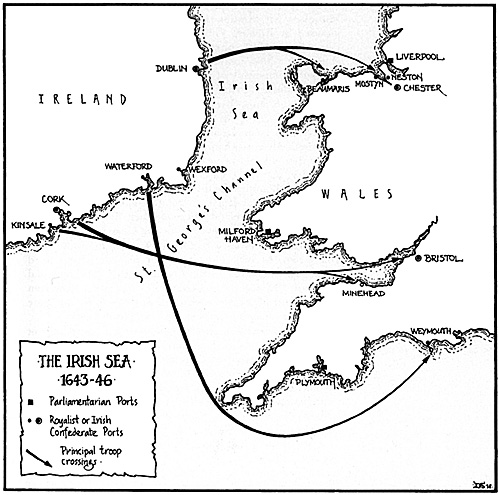

The initial problem lay in transporting the troops across

the Irish Sea, where the Parliamentarian Navy theoretically

enjoyed a considerable supremacy. The main force of

Parliamentarian ships in the area consisted of the so-called

"Irish Guard", mostly smaller fourth and fifth-rate vessels.

These were based on the south coast of England, with an

advanced base at Milford Haven. Fortunately for the Irish

forces, however, the Royalist successes during the summer of

1643 diverted much of the attention of the Parliamentarian fleet

during the period when the bulk of the troops were being

transported.

Another difficulty was lack of shipping,; we will

examine later how Ormonde tackled this problem in relation to

the major contingent from Dublin, but first we will look at the

forces brought over to South-West England from Munster.

Partly because of lack of shipping, and also because of

the nature of the military situation in Southern England, the

troops from Munster were brought over in a piecemeal

fashion, and used to strengthen the existing Royalist forces,

rather than being employed as a separate formation. The first

units to arrive, in late October 1643, were the Foot Regiments

of Sir Charles Vavasour and Sir John Paulet. They landed at

Minehead and Bristol, and were incorporated into the new

army which Lord Hopton was raising to advance into

Hampshire and the South East. The two units were each

between 4 and 500 strong, and were described by Hopton as

"bold, hardy men, and excellently well officer'd, but the

common-men were mutinous and shrewdly infected with the

rebellious humour of England, being brought over meerly by

the virtue, and loyalty of their officers, and large promises

[of pay] which there was then but small means to

performe." [6]

Disciplinary problems were common enough among the

troops from Ireland, but in the case of Vavasour's Regiment

proved particularly serious. The Irish troops were sent to join

in the siege of Wardour Castle, where matters quickly

deteriorated. Preparing to march to the relief of Basing House

"And not haveing heard of the proceedings of the Irish

Regiment at Warder, and doubting that nothing but money

would make them tractable, he [Hopton] went himself thither

from Winchester, and carried £ 30 with him; where

comeing to Funtill he was presently entertained by Sir Cha:

Vavaser and Lo: Arundell of Warder (who was then there)

with a complaint, that the regiment lying at Henden was in a

high mutiny against theire officers, in so much ad they durst

not adventure to come amongst them. Whereupon the Lo:

Hopton that night appointed a Rendezvous of Sir George

Vaughand's Regiment of horse, and of the two troopes of

dragoones neere Henden, and with them, the next morning

early fell into the Towne upon the mutineers, tooke some of

the Principals, and commanded the rest of the regiment to

drawe out. And upon that terror, and the execution of two or

three of the principale offendours, he drew the regiment

quietly to Winchester." [7]

Possibly because of this incident, or through ill-health,

Vavasour gave up his command, and was replaced by his

Lieutenant- Colonel, Matthew Appleyard, a capable

professional soldier, under whose leadership there was no

further evidence of mutiny. Sir John Paulet's Regiment was

also brought up from Bristol, and Paulet, "a bold hardy

man", with European experience, was appointed as

Hopton's Major-General of Foot.

The presence of these veterans from Ireland enabled

Hopton to take the offensive in December 1643, and both

were present at Cheriton on March 29th 1644. Here Appleyard

led a force of 1,000 commanded musketeers, who most

probably included some of the Irish troops, with considerable

success.

Both Regiments (described as Yellowcoats) were

present at the Aldbourne rendezvous of April 10th, and

served with the Oxford Army during the 1644 campaign, being

at Cropredy Bridge, Lostwithiel (where Appleyard again

played an important role in the Royalist attack) and II

Newbury. Whilst the evidence does not permit a detailed

assessment of their roles, it seems likely that the Irish troops

must have helped give some extra backbone to the King's

foot.

Paulet's Regiment was in Winchester garrison during

the winter of 1644/45, but took part in the Naseby campaign. The Regiment may still have totalled 5 companies at Naseby,

where it was effectively destroyed.

Appleyard's Regiment was involved in the storm of

Leicester, evidently playing a key role, for Appleyarrd was

knighted for gallantry and made Deputy Governor. Four

companies seem to have been at Naseby, and were lost there.

The next units arrived at Bristol in November. They

consisted of the Foot Regiments of Lord Kerry, which had

been raised in the West Country in 1642, now commanded by

Colonel Sir William St Leger, and that formerly commanded by

Sir William Ogle, now led by Colonel Nicholas Mynne. These

units had lost some 500 deserters prior to embarkation,

ostensibly because of supply shortages, and on reaching

England mustered between 800-1,000 men. They were

accompanied by about 300 of Lord Inchiquin's Regiment of

Horse under Captain Bridges. [8]

These units were despatched to reinforce Sir William

Vavasour, commanding Royalist forces in Herefordshire and

Gloucestershire, and enabled him to tighten pressure on

Parliamentary-held Gloucester. But in April, part of Vavasour's

force, including St Leger's Regiment, was added to the Oxford

field army. In April, St Leger's men, described by Symonds as

a 'full regiment", [9] were

lying at Marlborough, and were being re-equipped with pikes

and matchlocks from Oxford. In February, the Regiment had

been placed under the titular colonelcy of James, Duke of

York. [10]

The Duke of York's Regiment, possibly Redcoats,

continued to serve with the Oxford Army for the remainder of

its career. It was present at Cropredy Bridge, Lostwithiel and

11 Newbury (where St Leger was killed). In 1645, at Naseby, it

still seems to have been a fairly strong unit with at least six

companies. Henry Ireton was captured when he led an attack

on its pikes. Interestingly, two of the officers captured at

Naseby have possibly Irish names. [11]

So the Oxford Army was reinforced by three regiments

of foot from Ireland during the 1644 campaign. They may have

totalled in the region of 1,500 men, just over a quarter of its

total infantry. Whilst it is certainly too much to claim, as

Malcolm does, that the King would have been unable to have

taken the field without them, it may be that the markedly

improved showing of the Oxford Army foot during the 1644

campaigns, compared with its performance in the previous

year may have owed something to the veterans from Ireland.

[12]

Nicholas Mynne's Regiment remained on the Welsh

Border, its Colonel, favoured by Prince Rupert, succeeding

Vavasour as Colonel-General of the area. Mynne met with

little success, however, and was killed by Edward Massey at

Redmarley on August 4th, his Regiment being destroyed in

the process. [13]

Inchiquin's Horse, who probably included a number of

English settlers from Ireland, eventually made their way to the

West Country, and suffered a mauling at Dorchester, a

number of officers being captured and hanged. On the

defection of Inchiquin to Parliament, the Regiment changed

sides, and was shipped back to Ireland. [14]

The final major reinforcement from Munster arrived at

Weymouth in January 1644. It consisted of the Foot

Regiments of Inch in and Lord Broghill, each possibly about

800 strong. [15] They

reinforced Prince Maurice s Army, and were engaged in the

Siege of Lyme. Inchiquin's men captured Wareham in April 1644, and later garrisoned the

town. However, on Inchiquin's defection to Parliament in the

autumn of 1644, his Regiment surrendered, and was shipped

back to Ireland. Broghill's Regiment followed its example, after

serving, without particular notice, with Maurice at the siege of

Plymouth and Lostwithiel.

There was a final attempt to despatch troops from

Munster to the West of England in the spring of 1644.

Anthony Willoughby's Foot Regiment was shipped across,

but met with disaster at the hands of the increasingly active

Parliamentarian fleet. At least 150 of Willoughby's 400 men

were captured, and 70 of these were tied back to back and

thrown overboard by Captain Richard Swanley "under

the name of Irish rebels" (they certainly included a

number of men locally raised in Connaught). This incident

marked the effective end of "Irish" reinforcements for the

SouthWest. Not only the increasing threat of the

Parliamentarian navy, but also the demands of the situation in

Ireland, and shortage of shipping ended an effort which had

always lacked any clear strategic objective.

The story of the troops from Leinster, however, was

very different.

There were a number of factors which made the

potential of the troops stationed in Leinster, mostly in Dublin

and its environs, considerably different from that of the

troops from Munster. They were under Ormonde's direct

control, and the shorter sea crossing from Dublin to Royalist-

held territory in North Wales and North-West England made

their transport less difficult. Furthermore, naval strengths in

the northern part of the Irish Sea were more evenly balanced.

The Parliamentarian "Irish Guard" generally operated

further south, and the Navy's effective strength in the area

consisted of half a dozen armed merchentmen based on

Liverpool, which were effectively countered by the Royalist

John and Thomas Bartlett, with the naval fifth rate, "Swan"

and the armed merchantship "Providence". these, operating

from Dublin, proved able to keep the sea lanes open for the

Royalists for a fairly brief but critical period. These factors,

combined with wintry weather which further hindered the

Parliamentarian fleet, made it possible to bring over between 5-

6,000 troops from November 1643 to February 1644.

[16]

Unlike in the SouthWest, the prospect of being able to

bring over comparatively large numbers of troops fairly

quickly opened up the possibility of using them as a unified

force to carry out a more coherent strategic programme than

was either possible or necessary eleswhere. The long-term

aim, it was generally assumed in Royalist quarters, was to use

the Army from Ireland as a counter to the imminently expected

Scottish invasion. Arthur Trevor, in Oxford, expressed this

view in a letter to Ormonde on November 21st.

There seem to have been several proposals as to the

best way of initially employing the troops when they landed.

One was to use them to re-establish Royalist control of

Lancashire and Cheshire, a course urged by such local leaders

as the Earl of Derby. [18]

After fulfilling this objective, they could be used to bar any

Scottish incursion down the west coast of England.

Alternatively, the troops might winter in the North-West

before being used in the spring to reinforce either the King or

the Marquis of Newcastle. [19] The final option, and the one, partly through

circumstances, eventually adopted, was to leave the decision

to the commander on the spot, originally intended to have been Ormonde himself.

Though eventually the need for Ormonde's continued

presence in Ireland prevented him from taking up this

command, there were good reasons for the Royalists to feel

his presence with his troops to be desirable. For there were

considerable doubts concerning the reliability and loyalty of

many of the soldiers from Ireland. Even before they set out,

The King's Secretary of State, Lord George Digby, expressed

to Ormonde the Royalists' nightmare scenario: if "the armye that is transporting hither, considered as fatal to the rebels here, in case it come over and continue with hearty and entire affections, but folly as fatall to bid majesty's affaires in case it should revolt."

[20]

This fear was to continue to haunt the Royalists, and

give hope to their opponents, for some months to come.

Ormonde himself was gravely concerned, fearing the effects

of Parliamentarian agents who had been reported promising

the soldiers their arrears of pay if they should switch sides on

arrival. He warned the authorities at Chester, in whose vicinity

the troops were expected to land, that the troops "would

be apt to fall into disorders, and will think themselves

delivered from prisons when they come to English ground,

and that they may make use of their liberties to go whither

they will. And if the case bee such, that plentifull provision

cannot be instantly readie, it is absolutely needfull that a

compitent strength of horse and foote, of whoes affections

you are confident, sbould bee in readiness by force to keepe

the common soldier in awe- And whatever provision is made

for them, this will not be amiss."

[21]

A further concern was presented by the loyalty of the

officers, who were required to swear an oath of allegiance to

the King.

The next problem lay in finding sufficient shipping to

transport the troops. This was never fully solved, with the

result that the Leinster forces had to be carried across in three

waves, but Digby (responsible for arranging the reception of

the Irish forces in England) was able to despatch to Dublin

seven or eight Bristol ships under Captain Baldwin Wake,

which were reinforced by a number of vessels obtained by

Ormonde. [22]

The need for haste in bringing the troops over was

increased by the accelerating collapse of Royalist fortunes in

North-West England and North Wales. The local

Parliamentarians, under Sir William Brereton and Sir Thomas

Myddleton, in an attempt to pre-empt the landings, in late

October 1643 launched an offensive into North-East Wales

which led to a speedy collapse of Royalist resistance there,

and left Chester isolated. On November 16th, the first

contingent of Ormonde's troops sailed from Dublin.

This force consisted of about 1,850 men, under the

overall command of Sir Michael Earnley, an experienced

professional soldier. The troops with him included 400 men

(possibly all musketeers) of the Regiment of Sir Fulke

Hunckes, Sir Simoin Harcourt's Regiment (now commanded

by Richard Gibson), (700 men), Earnley's own regiment, (400),

part of Robert Byron's composite Regiment (200), again

possibly all musketeers, and the firelock companies of

Captains Thomas Sandford and Francis Langley, each 50

strong. [23]

Earnley's men disembarked without opposition on

November 21st at Mostyn in Flintshire. The Parliamentarian

invasion of North-East Wales promptly collapsed. After

making an apparently vain attempt to persuade the

newcomers to defect, [24] Brereton retreated into Cheshire, leaving a garrison

to hold Hawarden Castle, which, partly under the influence of

blood-curdling threats from Captain Sandford, surrendered on

4th December. The troops from Ireland had made their first

major contribution to the Royalist cause by saving Chester.

Probably in response to Ormonde's plea that other

reliable troops be on hand, on November 21st John Lord

Byron was despatched from Oxford with 1,000 horse and 300

foot. On arrival in Chester, Byron, who had been made "Field

Marshal-General of North Wales and those Parts" took over

command of the forces from Ireland.

[25]

On or about December 6th, the second contingent of

troops from Dublin disembarked safely at Neston in Wirral. It

consisted of the remainder of Robert Byron's Foot Regiment

(about 750 men), and Henry Warren's Regiment (about 500

men), together with three companies of dragoons totalling

about 140 men. [26]

They rendezvoused with the rest of Byron's command in

Chester.

The troops from Ireland had been wretchedly provided

for on arrival; it was noted that they reached Chester "in

very evill equipage..., and looked ad if they bad been used

hardship not having either money, hose or sboes, and 'faint,

weary and out of clothing."

[27]

However, in a remarkably successful piece of

organisation, the Royalist M.P. for Wigan, Orlando

Bridgeman, had organised the collection of both money and

clothing throughout North Wales and the Royalistheld area of

Cheshire. In Chester, the Mayor sent "through all the

wardd to get apparell of citizend who gave freely, dome

whole sutes, some two, some doubletts, others breeches,

otherd shirts, shoes, stockings and batts to the apparelling of

about 300." [28]

Unfortunately much of this apparent store of initial

goodwill was speedily dissipated. It has been claimed, notably

by Joyce Malcolm, [29] that the use of the troops from Ireland proved

severely damaging to the King's cause among a population

fed for years on stories of Irish and Catholic atrocities.

However, it should be remembered that the bulk of the new

arrivals were in fact natives of Cheshire and North Wales, with

friends and relatives in the area! Problems arose rather

because of the behaviour of the soldiers. Looting, of cattle

and other goods, seems to have begun immediately, many of

the men sold their donated clothing back again to the civilian

population, and brawling and robberies became a source of

increasing alarm to the citizens of Chester.

[30]

So alarmed were the civic authorities, that on Ist

December they offered at least £ 100 of the city plate to

the Royalist commanders on condition that "the soldierd be

removed sorth of the Cittie to quarters else wheere by Monday next."

[31]

Once active campaigning began, problems continued.

Byron was to complain of the hostility of the bulk of the

Cheshire population. This was, of course, partly due to the

fact that many of them were Parliamentarian in sympathy in

any case, but once again the behaviour of the troops, harshened by the brutal war in Ireland, played a large part. Looting continued to be widespread, and was worsened by incidents such as

the "mamacre" of civilians at Bartholmley on December 26th. [31]

Though there was in fact some strictly military justification for

this, it provided ready propaganda for the enemy, particularly after

Byron's letter to the Marquis of Newcastle, defending the action on

the grounds that "I find to be the best way to proceed with these

kind of people, for mercy to them is cruelty", fell into enemy

hands.

[1] Frank

Kitson, "Prince Rupert" (1994), p. 115.

Date Where Landed Number October 1643 Bristol and Minehead 900-1000* November 1643 Bristol 1300* November 1643 Mostyn, Flintshire 1800 December 1643 Neston, Cheshire 1500 Jan/Feb 1644 Neston/Beaumaris 1300 January 1644 Weymouth 1600* February 1644 Bristol 700 ?? February 1644 Whitehaven/Carlisle 2000??? March 1644 Neston/Chester 500 # April 1644 Bristol 400* June 1644 Scotland 2000# April 1645 North Wales ? January 1646 North Wales 160# [5] Total: 16200 *-indicates troops from Munster

# indicates "native" Irish.The "Irish" in the South

"A Cure for the Scots"

"The expectation of English Irish aydes is the

dayly prayers, and allmost the dayly bread of them that love

the Kinge and his business, and is putt into the dispensory

and medicine booke of state as a cure for the Scots"

[17].

Notes

[2] The exact total

strength of the government forces in Ireland at this date is virtually

impossible to calculate. In August 1642 they had, on paper, an

establishment of 42,800, but in reality were considerably weaker.

Numbers had dwindled still further in the interim. See Ian Ryder,

"An Army for Ireland", 1987.

[3] Thomas Carte, "life

J'Ormonde" vol V 5.

[4] Malcolm's findings

can be found in her "All the King's Men: the Impact of the Crown

lrish Soldiers on the English Civil War", in "Irish Historical

Studies", vol. XXI, No 83, 1979, pp.239-264, largely repeated in

her book, Caesar's Due: Loyalty and King Charles 1642-46",

1983. Malcolm's theisis is that the King's cause lacked widespread

popular support in England, and as a result he was forced to rely

heavily on help from elsewhere notably Ireland. Unfortunately, in

order to attempt to support her theory, the author relies heavily on

indescriminate and unsystematic use of Parliamentarian news

sheets, and other unreliable sources. Her statistics are devastating

and convincingly, indicted by R. N. Dore in his article "The Sea

Approached: the Importance of the Dee and the Mersey in the Civil

War in the North Weot"in "Trandactions of the Historic Society of

Lancashire and Cheshire, vol. 136, 1986, pp. 1-26

[5] Figures based in

part on Ryder, op.cit., pp.31-34, where full references are given.

[6] Ralph Hopton,

"Bellum Civile" (1902 ed) p. 62.

[7] ibid p. 64-5

[8] Ryder, og. cit. pp.

31, 33.

[9] Richard Symonds,

Harleian MS. 986.

[10] See Ian Roy (ed)

"Royalist Ordnance Papers", Oxfordshire Record Society, 1963/4

and 1975, pp. 137, 332, 425.

[11] Peter Young,'

Naseby"', P 78-79

[12] Malcolm, "All the

King's Men" pp.262-3.

[13] Ronald Hutton, "

The Royalist War Effort", 1982, pp. 148-9.

[14] Stuart Reid,

"Officers and Regiments of the Royalist Army",vol. III, p104.

[15] Ryder, op. cit.

p.33.

[16] See Dore, op. cit. P

1-4

[17] Thomas Carte,

"Life of Ormonde", vol. V, p. 52 1.

[18] ibid., pp 504-52.

[19] Clarenton, History

of the Great Rebellion", Vol.III., p.35.

[20] Carte, op. cit., vol

V., p.51.

[21] Ibid, pp. 505-6.

[22] see Dore, op. cit., 8-9

[23]

details drawn from Ryder op. cit., p. 31.

[24] A number of the

troops did temporarily leave their colours, but they were

apparently mainly local men taking self-granted home leave.

[21] This was not a

piece of self-seeking intrigue by Byron as is sometimes alleged,

but a clearly defined command intended to remain in force until

either Ormonde or some other senior commander was appointed.

See Ronald Hutton "The Royalist War Effort", 1982, pp. 123-4.

[26] See Ryder, op cit.,

pp.31, 32.

[27] HMC Vol. XX

App XI, p' 41 '; Harleian MSS (British Library) , 2125, f.135

[28] ibid.

[29] Malcolm, op. cit.

P.248.

[30] Chester RO

AF/26/4

[31] Chester Assembly

Book, f. 64v.

Back to English Civil War Times No. 54 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com