Background

Rupert doubtless understood the risk which he felt forced to take, and did what he could to minimise it. His main concern was for the key garrisons of Chester and Shrewsbury, and for the small town of Oswestry which guarded communications between them. In a command shake-up, the Prince appointed professional soldiers as Governors of each of them. At Chester he stationed the redoubtable Will Legge (his duties for the moment carried out by Sir Francis Gamull, Colonel of the City Regiment); at Shrewsbury Sir Michael Earnley (though his ill-health meant that command was delegated to another veteran of Ireland, Colonel Sir Fulke Hunckes). The new Governor of Oswestry was the former Deputy Governor of Chester, Sir Abraham Shipman, a career soldier from Nottinghamshire, who had proved competent enough in his previous appointment.

A more serious problem was shortage of troops. At Chester, apart from a few remnants of depleted units of Lord Capel's old command, Rupert left only Gamull's City Regiment of Foot, which in theory was only intended for strictly defensive duties, and Colonel John Marrow's Regiment of Horse. The latter, formerly an undistinguished formation raised by the local magnate Lord Cholmondeley, had been revitalised when Marrow, a veteran from the Army in Ireland, had taken over command in December 1643, and now bore comparison with some of the best field army units. [2]

At Shrewsbury the situation was little better. The only first line foot units were a detachment of Sir Michael Earnley's and Sir Fulke Hunckes" Regiments, both of which had been severely mauled at Nantwich. They had since received new recruits to fill out their ranks, but these lacked the experience of the veterans from Ireland. Also present was Colonel Randolph Egerton's Regiment of Horse, a not particularly outstanding unit.

[1]Sir Abraham Shipman at Oswestry seems to have been still less fortunate. His garrison consisted of fairly raw Welsh levies, notably, it appears, Colonel Roger Whitley's Flintshire -raised Foot Regiment. [3] As Byron among others was later to complain, the Welsh gentry who formed the bulk of the officers of such units tended to be "very inexact upon their duty", and the morale of the probably already unenthusiastic rank and file was not to be improved by the presence in the town of many of their dependents.

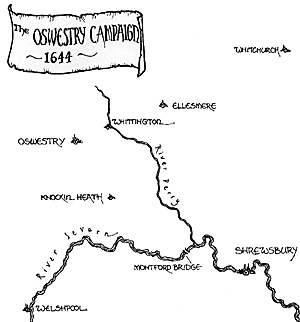

The local Parliamentarian commanders, Sir William Brereton in Cheshire, Sir Thomas Myddleton, Parliament's commander designate for North Wales, and Colonel Thomas Mytton of the Shropshire forces, were eager to take advantage of the current enemy weakness, but interest in Oswestry in particular was sparked off in the middle of June by reports that a Royalist ammunition convoy, "which we hear he standeth in need of very much", [4] probably from Bristol, was making its way north to Rupert in Lancashire by way of Oswestry. Thomas Mytton drew his own forces towards Chirk in the hope of intercepting the convoy, and on June 20th sent for aid to Basil Feilding, Earl of Denbigh, Parliament's Commander in Chief of the associated counties of Warwick, Worcester, Staffordshire and Shropshire.

Mytton pointed out that there was an opportunity to seize Oswestry, "which they are about to fortify very strongly". He was probably also influenced by information that Shipman was absent in Shrewsbury, where he had just taken a convoy of prisoners. Mytton had been further encouraged by a small victory on the previous day, when he had intercepted a company of over 50 musketeers en route for the small Royalist garrison at Bangor on Dee, and captured 27 of them.

Denbigh was fresh from his indecisive encounter with Lord Wilmot's detachment from the Oxford Army at Tipton Green on June 12th. He was currently persona non grata with a number of the Midland Parliamentarian leadership, who had accused him of disloyalty and assorted malpractices, so he may have been glad of an opportunity to demonstrate enthusiasm. However he had already been ordered by the Committee of Both Kingdoms to support the Lancashire Parliamentarians against Rupert, so could only bring his horse to assist Mytton. Denbigh's combined foot and horse had marched out of Stafford on the evening of Thursday, June 20th, but their march that night was retarded by "great rain". Next day, leaving his foot at Market Drayton, Denbigh headed for the Shropshire Parliamentarian headquarters at Wem, detaching some of his horse to Ellesmere, where they linked up with 200 Shropshire foot and a troop of horse.

Early next morning (June 22nd) the united Parliamentarian force advanced on Oswestry, arriving before the town sometime between noon and 2 pm.

In his "Itinerary" of Shropshire, compiled in 1539, the Tudor topographer John Leland gave a detailed description of Oswestry, which had not essentially altered a century later. The town was situated in a flat site in a valley, in "open treeless country". The town walls occupied a circuit of about a mile, and had four gates.

Just outside the New Gate stood the imposing structure of St Oswald's Church with its dominant tower and spire. According to Leland, the township within the walls consisted of ten principal streets, notably Cross Street, Bailey Street, where the market was held and Newgate Street. The most important buildings were the wooden Booth Hall or town hall, which stood near the Castle. This was still defensible, and was built on a mound surrounded by a ditch, on the south-west side of the town between Beatrice and Wallia Gates. Most of the houses were timber-built, with slate roofs. Suburbs had begun to develop outside the town walls, including many barns and storehouses.

Oswestry's strategic value, lying as it did on the main route into Central Wales via Welshpool, and close by the main Chester-Shrewsbury road, had been recognised from the early days of the war. It had been secured for the Royalists by Colonel Edward Lloyd of Llanvorda, but not much seems to have been done to strengthen the existing medieval defences, despite orders to that effect from Lord Capel in the summer of 1643.

When Denbigh's force appeared before the town, the defenders "gave us a hot salute, and our men as gallantly entertained it and returned an answer". The Parliamentarian forces began to deploy. Captain Keme of Denbigh's Regiment was sent with his own troop of horse and those of Colonel Barton, Captain Noakes, Captain Tompson and Captain Brothers to guard the Chester road, and send out scouts in the direction of Chirk, from which direction Marrow's Regiment was rumoured (incorrectly) to be approaching. More of Denbigh's horse, under Major Frazer, guarded the road to Shrewsbury.

The initial assault, by Mytton's 200 Shropshire Foot, was directed against the Royalist outpost in St Oswald's Church, and the Parliamentarians forced an entrance "after half an houres sore fight." The remaining defenders took refuge in the steeple, but "thence they fetched them down with powder", 27 prisoners being taken.

The Parliamentarians now moved against the town itself. A saker was brought up to within close range of New Gate, and, according to Denbigh: "We shot the gate through at two shots, and they fired from the gate at our men. But one of our shot striking a woman's bowels out, and wounding two or three, upset them in fear; that they betook themselves to the castle. We forced open the gate,and the horse entered resolutely, and by three o clock were possessed of the town - as good a piece of service (God hath all praise) as this year hath produced." According to one later account [5], after the gate was smashed by artillery fire, "a bold youth named George Cranage went with his hatchet, and let down the chains of the drawbridge, over which the horsemen passed immediately."

Denbigh himself led his Lifeguard of Horse into Oswestry, the Parliamentarian troops resisting the temptation to plunder as they pressed on towards the Castle. They met with little resistance in the town itself. Many of the more "timorous men" among the defenders slipped out over the town walls as the Parliamentarians entered, in an attempt to escape. They were not, for the most part, successful, a Captain and 14 men being rounded up and brought back as prisoners by Captain Kemes.

However the Castle remained in Royalist hands, held by the remains of the garrison, who had been joined by some of the terrified townsfolk. They appeared full of fight, and "fiercely fired upon us - every way being well manned. We made some shot with the great sacre, but they took little effect."

As darkness fell, Denbigh held a Council of War to consider his next move. The Castle was closely surrounded, and a party of troopers were sent forward in an attempt to fire the gate with pitch. But the weary soldiers 'slipped the opportunity", and Denbigh ordered Captain Kemes to repeat the operation at dawn. [6]

But, probably to that officer's relief ," on his way there met him a party of women of all sorts down on their kness confounding him with their Welsh howlings, that he was fain to get an interpreter, which was to beseech me to entreat my Lord, before he blew up the Castle, they might go up and speak to their husbands, children and the officers, which he moved, and my lord condescended to..." All was not quite yet over. Denbigh's terms offering life only were rejected by the defenders, who replied with their own propositions.

"First, to march away with our arms, bag and baggage, officers and soldiers, and all other persons whatever being in the said Castle, and

Secondly, that we, the said Officers, and all other persons whatsoever, being in the said Castle, may be guarded through your quarters to Montford Bridge, or quietly to abide in our own habitations.

Thirdly, that we may march out of the said Castle, over the said bridge, with our muskets charged, lighted matches, and balls in our mouthes.

These propositions being granted, the Castle shall be delivered by the officers subscribed. Denbigh rejected these proposals out of hand, and in the meantime the women, whom Kemes had left in the Castle, had renewed their persuasions on the troops. The result was that the defenders quickly changed their minds, and yielded on Denbigh's original terms. In the Castle the Parliamentarians found 100 good muskets, halberts, a barrel of powder and some match, some pistols and various other stores. They claimed to have taken prisoner a number of officers and 200 ordinary soldiers. Another version lists the prisoners as the acting Governor of Oswestry, Lieutenant-Colonel Bledwyn or Baldwin, Captains John Farrell, John Madryn, Thomas Tennant and Phillips, Lieutenants Nicholas Hook, Richard Franklin, Thomas Davenport, Cornets Leonard and Lloyd, Ensigns Morgan and Wynne , Commissary Richard Edwards. Nine sergeants and nine corporals were also taken, together with 305 soldiers, 80 townsmen in arms, 200 muskets, 100 pikes and 45 barrels of powder. The Parliamentarians admitted to losing 2 dead., 4 wounded, and one horse.

From the Royalist viewpoint it was vital to recover Oswestry. Operations were directed by Sir Fulke Hunckes, Governor of Shrewsbury, who drew in contingents from already depleted Royalist garrisons covering a wide area. According to Parliamentarian reports, elements from Chester, Shrewsbury, Wales, Ludlow and smaller garrisons as far away as Derbyshire were included. Estimates of total Royalist strength also varied considerably- 1500 foot and 600 horse according to Denbigh, 3,500 foot and 1500 horse in Sir Thomas Myddleton's version. On balance Denbigh's figure seems more probable.

In Oswestry Mytton had three foot companies of Sir Thomas Myddleton's, left behind by Denbigh because "they are grown soe weake that they are not able to guard their colours.,"- about 400 musketeers, and a "full troop of horse". He also had the services of a "great ingenier to secure that garrison". But work cannot have been very far advanced before the storm broke.

Mytton despatched news of the threat to the Earl of Denbigh, reaching him on June 27th when he was on the road to Knutsford. He warned the Committee of Both Kingdoms that "the enemy is now emptying all their garrisons and will venture all rather than not recover that place, which they concieve to be of so great concernmemt to their affairs." He urged that troops be sent to protect the area in his absence.

Details of Royalist operations against Oswestry are sketchy. It seems that the vanguard of their force, including Marrow's Regiment of Horse, began to close in around the town on June 28th. According to Sir Thomas Myddleton, the Royalists "endeavoured to storm the town by battering, and storming of the same, violently to have carried it", but it is not clear how far these operations actually got under way, though the attackers evidently retook St Oswald's Church. The evidence suggests that, apart from foraging in the surrounding area, the Royalists were still moving into position and siting two heavy battering pieces from Shrewsbury on July 2nd, when a Parliamentarian relief force was sighted.

The Earl of Denbigh had called a Council of War to consider the threat to Oswestry, and "after mature deliberation, and with the advise of the Council of War, I desired Sir Thomas Myddleton to take with him his owne horse, and the Cheshire foot, and to joyne with the foote in Wem, to raise the siege." Denbigh himself then rode to Manchester to consult with Sir John Meldrum, commanding the Parliamentarian forces there, and decided that it was unsafe to leave his own command in the current situation, and so, after detaching 500 Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Horse to join Meldrum and the remaining Lancashire and Cheshire forces in operations against Prince Rupert, set off for Oswestry, sending Myddleton word of his intentions to join him.

But, to Denbigh's considerable annoyance, Sir Thomas had not waited for his superior, but had already gone into action. The relief force included Sir Thomas Myddleton's Regiment of Horse, some Shropshire Foot from Wem, and the Cheshire Foot Regiments of Sir George Booth, Henry Mainwaring and Thomas Croxton, evidently drawn from the Nantwich garrison. Whilst the Parliamentarians may not have had many fewer foot than their opponents, it seems likely that they were outnumbered by the Royalist horse.

At about 2 o'clock on the afternoon of July 3rd, the relief force. approaching from the North-East, sighted Oswestry about three miles away. The Royalists had been aware for some time of Myddleton's approach, and Sir Fulke Hunckes was later to claim in his brief and self-justifying report to Prince Rupert that he had ordered Colonel John Marrow "to discover their strength, but expressly forbad him to engage himself, yet contrarie to my knowledge or direction, he tooke with him the whole bodie of horse, and was routed before I knew anything of it." How true this was is open to question; certainly it seems that Marrow attempted to hold the crossing of the little River Perry near Whittington, and "very firmly assaulted and charged us, but were repulsed, and forced to retire through the courage of our horse, who most courageously entertained the enemy. Three several times the skirmish was doubtful, either side being forced so often to retreat; but in the end, our foot forces coming up relieved the horse, beat back the enemy and pursued them with such force that the horse, thereby encouraged, which indeed was formerly weary, joining with the foot, they put the enemy to absolute flight.."

Denbigh, in his extremely grudging recognition of Myddleton's success, suggests that a key role was played by the Cheshire foot under Major General James Lothian, and it may be surmised that the Parliamentarians owed much of their success on this as on other occasions, to the effectiveness of the Cheshire musketeers. This is borne out by Sir Thomas Myddleton, who wrote of George Booth's men as "a gallant regiment, led by himself on foot to the face of the enemy", whilst the other Cheshire colonels were "all of them stout and gallant commanders, and the rest of the officers and soldiers full of courage and resolution. He described Lothian as "that brave and faithful commander, to whom I cannot ascribe too much honour, [who] brouht up the rear that day."

Whatever the rights and wrongs of Marrow's actions, he had at least given Hunckes, who claimed only to have left Shrewsbury with his main force on the previous day, time to begin his retreat. Hunckes alleged that his first news of Marrow's defeat came when "the first man I met with was Marrow all alone." However Sir Fulke certainly had sufficient warning to withdraw his foot substantially intact, falling back on Shrewsbury with his two heavy guns.

The Parliamentarians claimed "We killed of their men, about forty, and some of them proper handsome men and very well clad." Myddleton was rather vague about his own losses, admitting to losing several horses, 'some of out troopers, but no foot which I am yet informed of. " A Captain Williams was killed, and Fletcher , Captain Lieutenant to Colonel Barton, " a very courageous man", was 'dangerously shot." Myddlton's force pursued the Royalists as far as Felton Heath, about 4 miles South-East of Oswestry, "where we remained after their flight masters of the field."

The Parliamentarians claimed to have taken Captain Francis Newport, Captain Swynnerton, a reformado cornet, Lieutenant Newall, one quartermaster, two corporals, 32 troopers 200 common soldiers and 100 horses. Particularly gratifying to Myddleton's tired men were the large quantities of provisions which they found strewn along the Royalist line of retreat, including 'some whole veals and muttons newly killed." Also taken were seven carts, including one loaded with powder and ammunition.

Myddleton added with evident satisfaction: "The Town of Oswestry I find to be a very strong town, and if once fortified, of great concernment, and the key that lets us into Wales." The Earl of Denbigh, arriving on the scene too late to take any credit for the victory, was considerably less happy. Hinting darkly that the letters announcing his imminent arrival had been deliberately concealed, he went on to blame Myddleton's premature action for the failure to take Hunckes' guns.

However, making the best of the situation, Denbigh called an immediate Council of War, and decided to press on towards Shrewsbury, in the hope of following up their success by fomenting an uprising among Parliamentarian sympathizers in Shrewsbury, whom the Wem Committee claimed to be awaiting an opportunity to declare themselves.

Advance

On Thursday July 4th, after rendezvousing on Knockin Heath, the Parliamentarian forces advanced to Montford Bridge, spanning the River Severn, about 4 miles north-west of Shrewsbury. One arch of the bridge had been replaced by drawbridge, guarded by 40 Royalist musketeers and some horse, but Denbigh's foot gained the bridge after "a little dispute", the horse meanwhile crossing by a ford a couple of miles to the south-west. The Parliamentarians kept up the pursuit to within 1 1/2 miles of Shrewsbury, surprising Colonel Randolph Egerton's Regiment of Horse in their quarters, and capturing Major Fisher and some troopers. Suspecting, accurately enough, that the Royalists might be preparing an ambush, Denbigh called a halt to the pursuit about a mile from the town and drew up his forces on a heath. Here he received word that Marrow had advanced out of Shrewsbury and lined all the hedges between the heath and the town with musketeers.

Denbigh reported: "immediately I ordered the horse and foote to give on, who kill'd some on the place, drove the rest into the gates of the town, and my troope which led the van took Major Manley, major to the Lord Byron [10] and Governor of Bangor, within little more than pistoll shott of their workes. " Denbigh claimed to have taken a number of arms, and about 20 troopers and common soldiers, claiming that Marrow himself had only escaped through the goodness of his horse, but decided that the defences of Shrewsbury were too strong to assault. Hunckes, naturally enough, claimed that the Royalists had beaten off the attackers, who withdrew, burning Montford Bridge behind them.

With the relief of Oswestry, Denbigh had achieved his immediate objective, and, still ignorant of the Parliamentarian victory at Marston Moor on July 2nd, reverted to his original orders to assist the Allied forces against Prince Rupert. [11] Resuming their march north, the Parliamentarians captured the Royalist outpost at Cholmondeley House in Cheshire, but soon afterwards dispersed. Myddleton and Mytton began preparations for their campaign in mid-Wales. Denbigh's troops, discontented over pay arrears, retired to Stafford.

In the Royalist camp recriminations over the defeat continued. Hunckes endeavoured to shift the blame on to Marrow, though Rupert appears to have been unconvinced, for Hunckes lost his command in August. By this time Marrow was dead, mortally wounded in a skirmish on August 18th.

The loss of Oswestry had been a serious blow for the Royalists; henceforward their line of communications along the Welsh Border was subject to serious disruption, and the way was open for the Parliamentarian offensive along the Severn Valley which would result two months later in the Battle of Montgomery.

Denbigh's Forces -- June 1644

The following units had been with Denbigh at the Battle of Tipton Green, and probably formed the basis of his command at the capture of Oswestry.

[1] Byron to Ormonde, Carte MSS 15, f.465.

Virtually all the accounts of the Oswestry campaign, including the despatches of Denbigh, Myddleton and Hunckes, are reprinted in J. R. Phillips Memoirs of the Civil War in Wales and the Marches, vol II, 1874. The Royalist newspaper, Mercurius Aulicus, makes brief mention of the loss of Oswestry. Norman Tucker, Royalist Officers of North Wales, identifies some of the personalities on the Royalist side.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. By May 1644 Prince Rupert and Lord Byron had largely restored the Royalist position along the northern and central Welsh Marches, which had been threatened by the defeat at Nantwich in January. However, Rupert's plans to advance into Lancashire, with the primary objective of capturing Liverpool, and then of going to the relief of the Marquis of Newcastle, besieged in York by the combined Allied Armies, meant that the garrisons of the Welsh Border would be stripped dangerously thinly of troops in order to raise an army for the new campaign. Lord Byron for one was concerned by the problems which this might cause. Pointing out that Royalist forces along the border would be stretched very tight, he added "This falls out unlucky for the King's affairs in these parts, in the army is drawne hence, before these countyes can be reduced." [1]

By May 1644 Prince Rupert and Lord Byron had largely restored the Royalist position along the northern and central Welsh Marches, which had been threatened by the defeat at Nantwich in January. However, Rupert's plans to advance into Lancashire, with the primary objective of capturing Liverpool, and then of going to the relief of the Marquis of Newcastle, besieged in York by the combined Allied Armies, meant that the garrisons of the Welsh Border would be stripped dangerously thinly of troops in order to raise an army for the new campaign. Lord Byron for one was concerned by the problems which this might cause. Pointing out that Royalist forces along the border would be stretched very tight, he added "This falls out unlucky for the King's affairs in these parts, in the army is drawne hence, before these countyes can be reduced." [1]

The Fall of Oswestry

The New Gate lay on the south side of the town, the Black Gate opened south eastwards towards Shrewsbury, Beatrice Gate on Beatrice Street was on the route to Chester, whilst from Wallia or Mountain Gate emerged the road which ran north-westwards into Wales. There were no additional towers on the walls, but they were strengthened by a wet ditch filled by several nearby streams.

The New Gate lay on the south side of the town, the Black Gate opened south eastwards towards Shrewsbury, Beatrice Gate on Beatrice Street was on the route to Chester, whilst from Wallia or Mountain Gate emerged the road which ran north-westwards into Wales. There were no additional towers on the walls, but they were strengthened by a wet ditch filled by several nearby streams.

John Birdwell [7]

Lieutenant-Colonel John Warren

Captain Nicholas Hookes, Lieutenant [8]

Thomas Davenport, Lieutenant [9]

Hugh Lloyd, Ancient

Lewis Morgan, Ancient."The Royalists Strike Back

The capture of Oswestry was rightly seen as an important regional success. As Denbigh wrote: "This town is of greate concernment". Easy communications between Chester and Shrewsbury had been severed, and the way opened for a further advance along the Severn Valley into mid Wales. Denbigh appointed Mytton Governor of Oswestry, an action which made him unpopular with the Shropshire Committee, who currently were regarding Mytton with disfavour because of a prolonged absence in London, and headed back into Cheshire, to resume his interrupted march into Lancashire.

The capture of Oswestry was rightly seen as an important regional success. As Denbigh wrote: "This town is of greate concernment". Easy communications between Chester and Shrewsbury had been severed, and the way opened for a further advance along the Severn Valley into mid Wales. Denbigh appointed Mytton Governor of Oswestry, an action which made him unpopular with the Shropshire Committee, who currently were regarding Mytton with disfavour because of a prolonged absence in London, and headed back into Cheshire, to resume his interrupted march into Lancashire.

Large Map of Oswestry (slow: 92K)

Large Map of Oswestry (slow: 92K)

Jumbo Map of Oswestry (very slow: 172K)

Aftermath

Appendix

Earl of Denbigh's Regiment of Horse (400 men plus officers)

Sir Thomas Myddleton's Regiment of Horse (200 men)

Colonel Simon Rugeley's Regiment of Horse (150 men)

Colonel "Tinker" Fox's Regiment of Horse

Shropshire Horse (100 men)

Shropshire Foot (200 men)Notes

[2] See my forthcoming article on Marrow's Horse.

[3] Most of the officers captured at Oswestry are currently unidentified, though Tomas Davenport did serve in Whitley's otherwise obscure foot unit. It seems most likely that the garrison consisted of elements of this regiment plus other local Welsh troops and townsmen.

[4] Rupert had used up a great deal of powder in the siege of Liverpool, and his "York March" was partly delayed by the need to await new supplies from Bristol.

[5] A local (and otherwise unsupported) tradition quoted in Stackpole, The Garrisons of Shropshire during the Civil War, 1867, p. 68.

[6] The above local tradition credits the redoubtable George Cranage with blowing in the Castle gate with a petard, but no other source mentions such an occurrence, which seems unlikely to have happened.

[7] Also variously named Bledwell or Baldwyn, this officer remains unidentified.

[8] Probably of Conway.

[9] Roger Whitley, Foot.

[10] Most of Lord Byron's Regiment of Foot had accompanied Prince Rupert in his march into Lancashire. Possibly a company had been left to garrison Bangor on Dee, and some drawn out for the Oswestry operation.

[11] Operations around York immediately preceeding the Battle of Marston Moor were influenced by the assumption that the Allies were about to receive significant reinforcements under Meldrum and Denbigh. The latter's peregrinations around Cheshire and Shropshire, and the discontent of his men, suggest that in fact the Allies would have obtained rather less assistance than they (and perhaps Rupert) expected.

Sources

Back to English Civil War Times No. 53 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com