In her adulatory biography the Duchess of Newcastle wrote that "Amongst the rest of his army, my Lord had chosen for his own regiment of foot, 3,000 of such valiant, stout and faithful men (whereof many were bred in the moorish grounds of the northern parts) that they were ready to die at my Lord's feet..." (Ed. Firth p84) The notion of Newcastle having such a strong regiment has always appeared on the face of it to be inherently unlikely, particularly when coming from this source. Surprisingly enough however independent corroboration exists.

In her adulatory biography the Duchess of Newcastle wrote that "Amongst the rest of his army, my Lord had chosen for his own regiment of foot, 3,000 of such valiant, stout and faithful men (whereof many were bred in the moorish grounds of the northern parts) that they were ready to die at my Lord's feet..." (Ed. Firth p84) The notion of Newcastle having such a strong regiment has always appeared on the face of it to be inherently unlikely, particularly when coming from this source. Surprisingly enough however independent corroboration exists.

On the 29th July 1643 Captain Edward Ayscoghe, Sir John Meldrum and Colonel Oliver Cromwell sent to Speaker Lenthall what might be regarded as the official account of the battle of Gainsborough, the day before. (English Civil War Times 51 p31) After the utter defeat of Cavendish's cavalry early in the day the Parliamentarians were dismayed to discover what soon transpired to be Newcastle's whole army marching towards them. According to the official account the second regiment to appear was : "my Lord Newcastle's own Regiment, consisting of nineteen colours."(my emphasis)

With nineteen colours/companies, Newcastle's regiment must have been a double one with one Colonel's company (his own), two Lieutenant Colonels', two Majors' and fourteen Captains' companies. As the full establishment of an infantry regiment was theoretically 1500 men then the Duchess's reference to his double regiment being 3,000 strong may not be so wide of the mark. Ordinarily it would be surprising to find any regiment fully recruited up to its full establishment during the war, but the statement that he "chose" men from the rest of his army may be significant. If he was indeed foreshadowing Napoleon by drafting men from other regiments it is quite possible that his very own Imperial Guard was indeed maintained at something like establishment.

With nineteen colours/companies, Newcastle's regiment must have been a double one with one Colonel's company (his own), two Lieutenant Colonels', two Majors' and fourteen Captains' companies. As the full establishment of an infantry regiment was theoretically 1500 men then the Duchess's reference to his double regiment being 3,000 strong may not be so wide of the mark. Ordinarily it would be surprising to find any regiment fully recruited up to its full establishment during the war, but the statement that he "chose" men from the rest of his army may be significant. If he was indeed foreshadowing Napoleon by drafting men from other regiments it is quite possible that his very own Imperial Guard was indeed maintained at something like establishment.

As to the officers, it was originally proposed by the late Brigadier Young that the commander of the regiment was Sir Arthur Basset, but in the 1980s Dr Peter Newman suggested Sir William Lambton instead and the writer of this note has previously championed Colonel Posthumous Kirton.

Lambton's claim may be dismissed at once. Dr Newman has offered no evidence in support of his candidacy beyond the erroneous assumption that Lambton was the only northern infantry commander to die at Marston Moor and the quite astonishing theory that the regiment's supposed nickname, the 'Lambs' was derived from his arms carried on Newcastle's colours. In reality of course the Marston Moor casualties included three more of Newcastle's colonels; Posthumous Kirton and Sir Charles Slingsby were killed, while Colonel John Lamplugh was wounded and captured. As to the 'Lambs', Lilly, who appears to provide the earliest reference to it, explicitly links it with their wearing white coats. In any case contemporary accounts on both sides of the northern war refer to Newcastle's and Lambton's regiments quite separately.

The evidence regarding the other two, although hardly conclusive, is rather stronger and since Newcastle's was a double regiment it is probably safe to assert that both served in it at the same time.

As to Kirton little is known beyond the fact that he was evidently a professional soldier who served in the 1640 army and that his brother Theodore was Major in the Duke of York's Regiment. There seems no reason to doubt the traditional identification of him with the wild and desperate 'Coll. Skirton' who Fairfax describes as leading the decisive charge at Adwalton Moor. Since the Duchess states that 'my Lord's' regiment was the one which delivered the attack, it would follow that Kirton was then in command of it. He was of course subsequently killed at Marston Moor.

Sir Arthur Basset was not killed there and indeed was one of the officers who afterwards accompanied Newcastle into exile. His association with Newcastle's regiment rests on the evidence of the 1661 List of Indigent Officers wherein a number of former Cavaliers claimed to have served under him in Newcastle's regiment. Although this is by no means as reliable an indicator as it might be since it was common for officers to remember their general before their colonel, a process of cross-checking does appear to show a connection. Newman identifies him as Arthur Bassett of Umberleigh Co. Devon, a Trained Band officer who spent most of the war in the West Country. He quite rightly points out that there is no real evidence for him spending time in the north, let alone hanging around long enough to serve as the commander of Newcastle's own regiment.

In so doing however I feel that he fails to draw the obvious conclusion that Arthur Bassett of Umberleigh and the Arthur Basset who served under Newcastle are almost certainly two entirely different individuals. I also feel it is significant that Newcastle's first wife, who died in 1643, was the daughter of William Basset of Blore, Co. Stafford, and that the gallant Colonel was a near relation.

Distinctive Colours

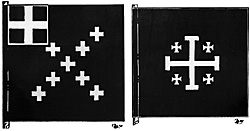

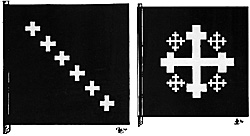

Judging by the official account of Gainsborough, the regiment's colours were quite distinctive. Included amongst the Allied trophies acquired at Marston Moor a year later were eleven colours described as 'red with white crosses'. These are almost certainly Newcastle's. It seems to have been the practice in the Royalist army for regiments commanded by General officers to have red colours, and the eleven referred to are clearly too many for an ordinary-sized unit. The mention of white crosses is unclear. It may simply mean that the several companies were distinguished one from another by varying numbers of white crosses on a red field.

Judging by the official account of Gainsborough, the regiment's colours were quite distinctive. Included amongst the Allied trophies acquired at Marston Moor a year later were eleven colours described as 'red with white crosses'. These are almost certainly Newcastle's. It seems to have been the practice in the Royalist army for regiments commanded by General officers to have red colours, and the eleven referred to are clearly too many for an ordinary-sized unit. The mention of white crosses is unclear. It may simply mean that the several companies were distinguished one from another by varying numbers of white crosses on a red field.

However the other trophies recorded in A True Relation of the Victory... (Thomason Tracts E59 19) are invariably described as having red crosses on white besides any other distinguishing marks. (Incidentally none of the colours bore Lambton's arms) This would suggest that on Newcastle's colours the St.George's cross normally displayed in the canton of infantry colours was either omitted, or perhaps even replaced by a white cross. The former is perhaps more likely. It is also possible that they may perhaps have been similar to those carried by Colonel Sir Henry Bard's Regiment.

In closing it is worth making two further points. In the first place although the regiment is usually referred to as wearing white, contemporary references on both sides allude to this being an emergency issue of clothing shortly before the siege of York. Earlier, if the Duchess's account is to be relied upon they wore red. There is also a very widespread belief that in Newcastle's army infantry regiments could only field equal numbers of musketeers and pikemen. However there is absolutely no evidence to support this unwarranted assumption. On the contrary, unlike the Oxford Army, Newcastle's men were receiving arms shipments directly from the continent.

Apart from the large quantities brought by the Queen and turned over to Newcastle's army (only the powder and artillery was passed on to Oxford), a steady procession of gun-runners passed through the Tyne. There is no reason therefore why Newcastle's Regiments should not have been achieving ratios of 2:3 or even 1:2 pikes to muskets.

Back to English Civil War Times No. 53 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com