Thomas Lord Grey of Groby, the eldest Son of Henry Grey the Earl of Stamford, Midland Association Commander during the English Civil War and prominent MP during the Interregnum, was born into one of the most noble families in England. A family which had included Lady Elizabeth Woodville, the Wife of King Edward IV and also the prestigious but unfortunate, Lady Jane Grey who was Queen for June nine days.

Thomas Lord Grey of Groby, the eldest Son of Henry Grey the Earl of Stamford, Midland Association Commander during the English Civil War and prominent MP during the Interregnum, was born into one of the most noble families in England. A family which had included Lady Elizabeth Woodville, the Wife of King Edward IV and also the prestigious but unfortunate, Lady Jane Grey who was Queen for June nine days.

There have been many schools of thought amongst historians concerning the causes of the English Civil War from whiggish to Marxist and a revisionist theory. However, Leicestershire would fit classically into the factionist theory. This is because the Greys were not the only great family in Leicestershire. They had competed for royal patronage since the Wars of the Roses with the Hastings family.

The Hastings lived at Ashby Castle and had included such noblemen as George Villiers (the once favourite of James I) in its lineage and it was no surprise that they were to side with the Royalist cause during the Civil War.

The fact that the Hastings family had sided with Charles I and that they were higher in position in the noble families than the Greys, possibly had a great bearing upon Henry Grey siding with parliament. However, it becomes apparent that Thomas Grey not only pledged his allegiance to Parliament because of his Father and the hated Hastings, but also because he was a staunch Protestant and wanted further Godly reform and feared Charles I popish plot.

In March 1642, Henry Grey was made Lord Lieutenant of Leicestershire by a parliamentarian ordinance and the Records of the Borough of Leicester record that parliament in March 1642 ordered the warrant for raising of the militia. "In accordance the Earl of Stamford named his son, Thomas Lord Grey of Groby as being responsible for ministering the training the forces of Leicestershire". [1]

On December the 13th 1642, Henry, Earl of Stamford, was appointed Lord General of South Wales, Hereford, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire and Cheshire. His Son, Thomas Lord Grey of Groby, was appointed Lord-General of the Midlands Association of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Rutland.

"They were both given power to raise forces and appoint officers and commanders, to train and exercise them to fight with, kill and slay all who came against them. It appears that the younger Lords area of jurisdiction was tended for on the 15th December, Northamptonshire, Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire and Huntingdonshire were added to his Midlands Association". [2]

This was because the entrenched localism of the Militia's was a constant problem for the armies during the English Civil War, and the parliamentarian army was restructured in 1642 into larger areas comprising of sets of counties in an attempt to overcome localism (see Coward The Stuart Age). By the end of May 1643, Lord Grey of Groby had concentrated an army of between 5,000.00 and 6,000 men. [3]

Lord Grey garrisoned his troops at Kirby Bellars, Thurnby, Abbey, Bagworth and later at Coleorton. The Greys lived in one of the most magnificent brick built houses in England, set amidst parkland at Bradgate in Leicestershire. The park can be visited today but the house stands in ruins after a fire in the time of Harry Grey - the third Earl of Stamford who lived in the Eighteenth Century. After this fire the house was never repaired and the Grey family built a new house at Dunham Massey in Cheshire. It is at Dunham Massey where one can view the portraits of Thomas Grey and his Father, Henry the first Earl of Stamford.

Prince Rupert and Colonel Hastings brought a troop of Royalist horse to storm Bradgate only four days after the Civil War began. However, neither Thomas nor his Father were there and there was very little damage done other than seizing some ammunition, frightening the maids and taking the chaplains clothes.

Thomas' military action began when he was just nineteen years old, when Lord Thomas Grey's troop, part of Sir William Balfour's Regiment travelled to Edgehill and during the battle "fought on the Earl of Essex's right wing". [4]

In August 1643 John Nicholls writes that "The Lord Grey showed his attachment to the Earl of Essex, the parliament General, by hastening to the nobleman's rendezvous at Aylesbury, with his regiment and a large body of foot belonging to the associated counties, which enabled the General to reach Gloucester in time to prevent its surrender". [5]

Three days later, Lord Grey obtained a comprehensive victory over the royal army at Newbury. Subsequently one finds in the journals of the House of Commons [6], that "in the thanks, which were on this occasion, voted by the House that The Lord Grey stands the foremost".

"In February 1643, the Queen had landed at Bridlington Bay, with ammunition and weapons which she had purchased in Holland. In the Midlands, Sir John Gell and Oliver Cromwell realised that, in order to prevent her reaching the King, they had to attack Newark. For this enterprise they would need the support of the Lord Grey's Regiment". [7]

It is well documented that Lord Grey was late at his rendezvous with Cromwell, and an argument ensued. Lord Grey was involved in an incalculable amount of local skirmishes, including the siege of Ashby Castle and the Battle of Cotes Bridge.

A Parliamentarian soldier wrote, "our army came to Loughborough and we were joined by Lord Grey's regiment. They fired a canon at the enemy, which killed a great many of their men and forced the rest to retreat. Learning that Prince Rupert was not far off, with 2,000 cavalry and as many soldiers on foot we retreated towards Newark and Lord Grey towards Leicester"

[8]

On April 15th 1643, The Committee for the safety of the Kingdom were ordered by the House of Commons "to furnish my Lord Grey of Groby with six pieces of ordinance and one thousand muskets and to send them hence with all speed". [9]

In 1644, Lord Grey's Regiment took the Royalist garrison of Wilne Ferry in Derbyshire and in February 1644, it was reported to the House of Commons that "a part of Manchester's foot and horse out of Lincolnshire were joined by Lord Greys foot and horse at Melton Mowbray", there they relieved Melton. There are numerous primary sources which give reference to Lord Grey's regiment of foot for instance a letter from Lord Grey dated July 1st, which appears in the Diary of Parliamentarian Proceedings on July 4th, 1644 states "he marched thence on the Lords day before, with 200 foot and 50 horse to Stamford, and hearing of a scattered force of the enemy that were quartered about Belvoir and Ashby, he wheeled about and encountered a party of them. He killed 5 or 6, took 40 horse and many gentleman of quality, one Lieutenant, 2 cornets and some others".

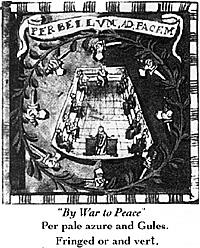

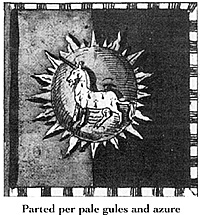

We have two recorded standards for Lord Grey and his regiment, one showing a unicorn set in a golden sun (from the Grey's Coat of Arms), upon an azure and glues background. The other also on an azure and glues baground shows a laurel wreath, with hands holding daggers guarding the Parliament building, with Lord Greys motto being 'by war to peace'.

[10]

It is extremely doubtful that Thomas Lord Grey's regiment of foot ever progressed into the New Model Army, and is not mentioned in Firth; also the Directory of National Biography (Volume XXIII), informs one, that in 1648 Grey raised his regiment in Leicestershire and "after the defeat of the Scots at Preston, he pursued the Duke of Hamilton and his horse to Uttoxeter. Grey claimed the credit of Hamilton's capture and although Hamilton declared himself to have surrendered to Lambert, Parliament admitted Grey's claim and voted him their thanks".

[11]

In August 1651, Lord Grey was sent to raise volunteers with the commission of Commander and Chief of all the horse he should raise in the counties of Leicester, Nottingham, Northampton and Rutland to meet the Scottish invasion. In September after the battle of Worcester, Massey surrendered to Grey.

There seems to have been a difference of opinion upon the nature of Grey's character "Clarendon says, a man of no eminent parts, but useful on account of his wealth and local influence". Whereas, "Mrs Hutchinson speaks of "his credulous good nature" and he seems to have been a favourite of Essex". [12]

Thomas Grey married Dorothy, second daughter and heiress of the fourth Earl of Bath and their only son, Thomas became the second Earl of Stamford in 1673.

On November 25th, 1648, Lord Grey was nominated for the County of Leicestershire, to take care to bring in the assessments of the army. [13]

It has been argued that the first Civil War was a rebellion rather than a revolution and the purging of parliament was actually the English revolution in December 1648. If this is so, then Lord Grey was integral in the revolution as it was Colonel Pride and Lord Grey whom purged parliament in December 1648. Nichols writes "he had always been an advocate for violent measures; and when Colonel Thomas Pride, under the orders of the Council of Officers, undertook to garble the House of Commons his Lordship was the prime mover and agent in the transaction".

Thomas Grey's signature appears as the second signature upon Charles I death warrant, but it is a recorded that his Father, Henry Grey the Earl of Stamford said "Thomas, no king no Lord", thus highlighting his dislike. At Charles I's trial, the King referred to Lord Grey as the 'grinning dwarf'. Lord Grey continued in the forefront of politics in the interregnum and Nichols writes "so far he had been trusted, courted, applauded and gratified, chiefly by Cromwell; but, as this great man Grey was as ambitious as himself, or at least that he could not brook a superior, he began to treat him with less confidence and at length to watch him as a dangerous person. They probably cordially hated each other. He feared Cromwell and regarded him as a revloter from the common interest; and Cromwell knew that a man who had been untrue to his sovereign could not be expected to one whom he viewed as inferior to himself. Outwardly, however they behaved with seeming attention to each other, whilst each was watching for the favourable moment to ruin his enemy. Oliver dared not trust him in London he therefore kept him in his station in Leicester, but that being the central situation of the kingdom and in case of a revolt, a very dangerous one for a person of Lord Grey's consequence and turn of mind he kept constant spies upon him". [14]

On February 12th, 1654 Cromwell arrested Grey and took him to Windsor Castle, possibly because of his involvement with the fifth monarchists. Grey was released and pronounced head of the Fifth Monarchists then as Cromwell was keen to return to stability during his protectorate imprisoned Grey again. Grey was to die in 1657 most probably of gout.

In the weeks following the execution of the King, expectations of the millennium were at fever pitch. There is little doubt that millenarianism was part of the mainstream of English intellectual life in the first half of the Seventeenth Century. The Fifth Monarchists flourished in the early 1650's. Central to their philosophy were the biblical prophecies in the Books of Revelations and Daniel, which had been the subject of ingenious speculation for centuries.

Like many other before them, the Fifth monarchists interpreted the prophecy in Daniel VII, that after the rise and fall of four great empires a kingdom would be established that would last forever to mean that Christ's Kingdom - the fifth monarchy - would follow the collapse of the four great empires of Babylon, Persia, Greece and Rome. Using this and other interpretations of key old Testament Prophecies the execution of King Charles (the little horn in Revelations) was to sign for the establishment of the reign of King Jesus. Ludicrous as these ideas seem they were well in line with those held by many people in the mid Seventeenth Century. Cromwell for a time was closely connected with the Fifth Monarchists.

The parliaments of the Rump and Barebones struggled to achieve a status quo between the army and religious groups in their quest for a godly reformation and return to stability. However, the protectorate years of Cromwell was primarily concerned with stability and Lord Grey possibly became a victim of this.

Thomas Lord Grey was a conspicuous figure throughout the Civil War and Interregnum. Unfortunately very few of his papers survived as there were two great fires at Bradgate in the Eighteenth and also in the early part of this Century.

[1] Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society Transactions Volume LV1 1980-81

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. However, Thomas Grey was in a precarious position when leaving Leicestershire, as it left Leicestershire vulnerable to Hastings of Ashby and so left a corridor through the county for the King to supply himself from his only port, Bridlington to supply his forces in Oxford.

However, Thomas Grey was in a precarious position when leaving Leicestershire, as it left Leicestershire vulnerable to Hastings of Ashby and so left a corridor through the county for the King to supply himself from his only port, Bridlington to supply his forces in Oxford.

NOTES

[2] The Civil War in Leicestershire and Rutland - Philip Scaysbrook pp 38-39

[3] The English Civil War, Brigadier Peter Young and Richard Holmes

[4] Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society Transactions Volume LVI 1980-81

[5] The History and Antiquities of Leicestershire Vol II Part II, John Nichols

[6] House of Commons Journals Volume III page 256

[7] Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society Transactions Volume LVI 1980-81

[8] The Civil War in Leicestershire, Douglas Clinton

[9] House of Commons Journals

[10] Republica, Prestwich pp 27,28, 35

[11] Lives of the Hamiltons ed 1853 Burnet pp 461. 491

[12] Dictionary of National Biography

[13] The History and Antiquities of Leicestershire Vol III Part II, John Nichols

[14] The History and Antiquities of Leicestershire Vol III Part II, John Nichols

Back to English Civil War Times No. 53 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com