FIRELOCKS 1646-1660

Unlike the earlier period above, the use of firelocks in the New Model Army does not appear to have been specifically limited to specialist companies as when it was originally formed the issue of firelocks seems to have been extended to every regiment of foot. In the Ordnance papers over 3,300 firelocks were supplied to the army between 1645-46, far in excess of the numbers required by the two companies of firelocks guarding the artillery train or Okey's Dragoons, even accounting for replacements due to losses in the field. [33] Instead, it would appear that a number were issued to every company in the army for the purpose of sentry duty. Although dating from a little later, a return of May 1650 for the re-equipping of Colonel Walton's company lists the issue of 66 muskets of which 6 were firelocks. [34] Assuming a similar proportion to each of a regiments ten companies (10 to the larger Colonel's and Lieutenant-Colonel's companies and 8 to the Major's company) then a regiment would have had around 80 to 100 firelocks. With twelve regiments of loot in the original New Model Army, then the 3,300 firelocks would appear about correct.

This practice of the general issue of firelocks would seem to have already been developing prior to 1645. Back on 15th. November 1643 an official return for the arms necessary to equip Colonel Edward Harley's regiment of Foot to its regulation strength of 1,200 men recorded a requirement of 800 muskets of which 150 were to be firelocks. [35]

The Ordnance Papers for post 1646 show a continuing high level of firelocks being ordered and delivered to the army. Some would appear to have been for specific firelock companies. For example, in 1647 it is listed that two un-regimented companies of firelocks were landed in Dublin. [36] Yet the above return for Colonel Walton's company indicates that a proportion were being issued to all companies of Foot. For example, after the reduction of the old London Trained Bands due to their questionable loyalty to the new regime in 1650, new "London Volunteer Regiments" were raised by the Commonwealth. An order for 28th August 1650 details some of their equipment as "1,000 matchlock muskets, 500 snaphance muskets, 500 pikes, 1,500 bandoliers and 2,000 swords". [37] One might speculate that the high proportion of firelocks was to guard the Tower with its magazine of powder.

Another indication that the role of the firelock was becoming recognized was in the text of the 1650 military manual of Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Elton "The Compleat Body of the Art Military". Certainly reflecting the state of military thought after the First and Second Civil Wars, Elton states in relation to the artillery,

"Those which are ordained for their guard to be firelocks or to have snaphances for the avoiding of the danger that might happen by the coal of the match".[38]

It is interesting that Elton distinguishes between the firelock and snaphance as distinct mechanisms suggesting that both were still in use in the late 1640's.

ACTIVE SERVICE

Three examples of the Protectorate Army on campaign demonstrate the established role of the firelock by the 1650's.

SCOTLAND 1653-54

The important role of firelocks in outpost and irregular warfare was forcefully demonstrated in the suppression of Glencairn's Royalist uprising in Scotland. In a letter to General George Monck in early 1654, Colonel Robert Lilburne stressed the need for "some more firelocks" to help counter the Highlanders guerrilla tactics. [39] The operational advantages of the firelock, with its instant readiness for action and the fact it did not give away the presence of its holder, were at a premium.

JAMAICA 1655

General Venables' expedition to the West Indies in 1655 received some 4,000 muskets from the Tower of which 1,000 were "snaphance" along with ten tons of "flint stones", purchased at 13s 4d per thousand. [40] There was also a specific company of firelocks attached to the train of artillery under the command of a Captain Johnson which had a strength of 12 officers and 120 men. It is also possible that one company in each of the six infantry regiments were armed with firelocks as certainly, in General Venables own regiment, Captain Pawley or Pawlet's were so armed. [41] In the early stages of the campaign Captain Pawlet commanded a specific force of firelocks which operated in text-book fashion. With the very first landing on 14th April 1655 on the Spanish Island of Hispamola Captain Pawlet's firelocks formed part of the scouting force. According to a contemporary account there were "Captam Pawlet's firelocks on both wings in the woods to discover ambuscados". [42] Pawlet's firelocks continued to operate as part of the advance guard, scouting ahead of the main force until largely destroyed on 25th April before the City of San Domingo. [43]

FLANDERS 1657

Here too, the firelocks were to the fore. There is no specific surviving warrant for the issue of firelocks to the infantry regiments raised for the army that served in Flanders. Having said this, at the Battle of the Dunes on 4th June 1658, two contemporary accounts by the senior officers of that force give prominence to the Protectorate force having a body ot 400 firelocks. The overall commander of the English force, General Sir William Lockhart (previously Cromwell's ambassador to France but appointed to overall command with the death of the original commander General Reynolds), related how some detachments of picket foot (firelocks) were sent out to be stationed amongst the squadrons of French horse on the right wing. These 'four hundred firelocks' were then recalled and ordered to take part in an attack on a strongly defended sand-hill on the right wing of the Anglo-French army. He related how the body of firelocks fired on two sides of this sand-hill which was inaccessible to assault whilst two infantry regiments assaulted its front. Then the firelocks supported Lockhart's own Blue Regiments assault on the Spanish front which won the day. [44] A second account, by Major-General Sir Thomas Morgan, supports this and gives further details. He initially places them on "...the right wing with the Blue Regiment, and the 400 Firelocks which were in the intervals of the French Horse;..". Then, supported by the Blue and the White regiments, "...the 400 Firelocks shock the enemy's right wing off the ground". Finally, Morgan ordered "...the Blue Regiment and the 400 Firelocks to advance to the Charge."[45]

Both Lockhart's and Morgan's accounts makes it clear that the firelocks operated as a specific unit on the field of battle. Their total number equated to the 75 odd firelocks (each company having a file of such) one would have expected to find in each of the six regiments of foot and it would seem fair to conclude that the firelocks of each regiment had been temporarily drawn together as the battle commenced. This practice appears to foreshadow the later 1670' and 80's practice of forming the grenadier files from each of the ten companies of a battalion into a single formation for combat (grenadier companies did not exist in the English army until the start of the eighteenth century). Interestingly, the initial deployment of the firelocks in the intervals between the French squadrons of horse recalls Prince Rupert's deployment of commanded shot in the intervals amongst the royalist horse at the Battle of Naseby.

THE SUPPLY OF FIRELOCKS

To support the contention that the use of firelocks was increasing one would expect to find that the production of such weapons was also increasing. While the records for the Royalists are inconclusive in this respect, those for Parliament are not. The records for the gunmakers William and John Watson are complete for the whole period 1642-1651 and they demonstrate a tremendous increase in the proportion of firelocks being manufactured relative to matchlocks.

The Watson family were central to Parliament's manufacture of firearms. While the period 1642 to early 1645 saw the major importation of Continental weapons, especially from Holland, from early 1645 domestic production for Parliament largely took over, especially from the London Gunmakers Company based just outside the Tower in the Minories. Formed in 1637 it consisted of 53 gunsmiths who were Freeman of London and 62 who were not. Between them they were able to manufacture literally thousands of weapons a month if required and one of the largest manufacture was the Watson family. In fact, in 1646, William Watson was to become Master Gunmaker and Proofmaster to the Ordnance itself.

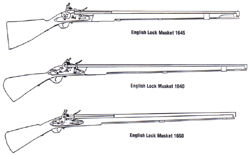

By breaking down into three seperate periods the Watson's delivery of weapons the vast increase in the use of the firelock becomes obvious along with the decline in the unit cost of manufacture. It should be noted that in these orders, the contemporary term still used was "snaphance" although by 1642 all weapons labelled snaphance were recognisably firelocks/flintlocks of either the "English Lock" or "Dog Lock" variety.

- March 1642 to December 1644 = 400 "Muskets with snaphance locks and bandoleers" at 20s each (matchlocks were then 16s each). [46]

- January 1645 to June 1646 = 2,300 "snaphance muskets to be English full bore and proofe" at an average cost of 15s.6d each (matchlocks were then 11s each). [47]

- July 1646 to September 1651 = 4,463 snaphance muskets, ranging in price from 12s each in November 1646 to 15s each in October 1647. Of these, 900 were for the navy and 3,563 for the army. In addition, on 17th September 1650 they specifically delivered "400 Snaphance Dragoons" at 13s each.

During the same five year period, up to 1651, the Watsons delivered some 5,000 matchlock muskets for as little as 10s each. The Watsons also supplied flints, for example, on 9th December 1650, "Flint stones for snaphance muskets and pistolls 12000 at 23s.4d per thousand'. [48] As the above statistics demonstrate, by the later period 50% of the Watsons output were firelocks, just short of 5,000 in total as compared with just 400 at the commencement of the war. That these were full length snaphance muskets and not cavalry carbines is demonstrated by the following specifications of one of the orders for the original New Model Army contract, a delivery of 22nd December 1645 was "for 600 Snaphance Musketts full bore and proofe and four foote longe and 14s.4d each."[49]

While the Watsons were the largest single company, there were others adding to this total. For example, on 12th March 1652 the Committee of the Ordnance placed an enormous order for the Commonwealth Navy for 5000 matchlocks and 2000 snaphance muskets, along with 1500 pairs of pistols. This order was divided between fifty-eight gunsmiths of the London company and it was fully delivered within eight weeks, one Robert Murden's share being 50 matchlock and 30 snaphance muskets, and 30 pairs of pistols, while a Ralph Venn's share was 150 matchlock and 40 snaphance muskets, and 25 pairs of pistols. The Watsons only supplied 150 matchlock and 60 snaphance muskets, and 35 pairs of pistols for this particular order. [50] One can hence judge the enormous manufacturing capacity which had now become available even for the supposedly complex mechanism of the firelock.

CONCLUSION

By the late 1650's the firelock had seemingly become an established proportion of the firepower of all foot regiments and one might have expected this to have continued under the Restoration. Initially this appears to have occurred as George Monck issued warrents to arm four companies of his regiment entirely with firelocks in February and April 1660. This though gives a misleading impression as these four companies had the task of guarding the Tower of London with its strategic arsenal and so issuing them with firelocks was necessary solely for that role. When these four companies left the Tower in 1664 they were entirely re-equiped with matchlocks. [51]

In fact, initially at least, the small Restoration army stationed in England equipped its infantry with matchlocks, seemingly without any proportion of firelocks prior to 1664. The reason for this was simple, MONEY, the matchlocks were cheaper. Further, this small army was primarily involved in maintaining domestic order and the hardier matchlock mechanism stood-up better to the rough usage of crowd control. One element of the new army did though maintain a significant proportion of firelocks which were the regiments forming the garrison of Tangier, as before, operational requirements were the deciding factor. It should be added that by 1662 the majority of the garrison of Tangier were drawn from the ex-Protectorate Regiment of Lillingstone, then Sir Robert Harley's Regiment (later the 2nd Foot, The Queens), that had been garrisoning Dunkirk and as their original organisational structure was maintained they brought with them their firelocks. [52] As the century progressed and the new army became involved in new wars, the proportion of firelocks to matchlocks did inevitably increase as its innate operational advantages outweighed its greater initial cost and more delicate mechanism until the ultimate demise of the matchlock in the English Army by 1703.

Part 1 - Firelocks 1642 - 1646

List of References

Back to English Civil War Times No. 51 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com