THE BACKGROUND

Built on a sandstone crag, 160 metres above sea level, with precipitous drops on two sides to the Cheshire Plain below, Beeston Castle still dominates the surrounding countryside. The strategic importance of the site was recognised as early as the Bronze Age, when the hilltop was fortified, but the Castle itself was constructed by Ranulf de Blundeville, sixth Earl of Chester, after 1225. Its original purpose was to guard against Welsh incursions through the Peckforton Gap, cover communications from Chester to the Midlands, and to act as a superb observation post over miles of surrounding terrain.

Beeston 's history during the first four hundred years of its existence - apart from being a rumoured hiding place for King Richard II's treasure - was comparatively uneventful, but on the outbreak of Civil War in 1642, its strategic value again became apparent.

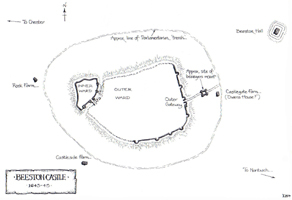

The Castle consisted of a large Outer Ward on the lower slopes of the crag, with a fortified gatehouse, and a curtain wall, with an uncertain number of towers set at intervals around it, and, occupying the summit of the crag, and separated from the Outer Ward by a deep ditch cut into the rock, an Inner Ward, with gatehouse, walls and towers, protected on three sides by precipitous cliffs.

Described by Camden in the previous century as "A place well guarded by walls of a great compass, by a great number of towers and by a mountain of very steep ascent", by 1642, Beeston had fallen into considerable disrepair, and was summed up as "no more than the Skeliton or bare Anatomy of a Castle". [1] None the less, as it became evident that the conflict would be prolonged, the importance of securing Beeston became increasingly clear.

PARLIAMENTARIAN CONTROL

Arriving in January 1643 to take command of the Parliamentarian war effort in Cheshire, Sir William Brereton, who "prized it by its situation", lost no time in occupying Beeston before the Royalists preempted him. On February 20th he stationed a force of 2-300 men in the Castle, and after they next day got the better of the Royalists in a skirmish in nearby Tarporley, the Parliamentarians set to work to make Beeston both defensible and habitable.

Brereton ordered "the breaches [in the walls of the Outer Ward] to be made up with mud walls, the well of the outer ward to be cleansed, and a few rooms erected." [2] Archaelogical evidence suggests that the latter consisted of some timber buildings in the Outer Ward, replacing original constructions which had fallen into ruin. The Parliamentarian Governors seem to have established their quarters in the towers of the Outer Gateway, which was further strengthened at this time by some apparently rudimentary outworks outside it, and a new wooden gateway. [3] Not a great deal else seems to have been done at this point to strengthen or modernise the defences, and, during the spring and summer of 1643, as the Parliamentarians gained the upper hand in Cheshire, Beeston seems to have been increasingly viewed as a quiet backwater, precautions were relaxed, and the garrison reduced: "A captain or two being wearied out of the charge of such a prison, it was committed to Captain [Thomas] Steele (a rough-hewn man; no soldier) whose care was more to see it repaired, victualled and live quietly there, than the safe custody of it." [4]

Steele, a cheese-factor from Nantwich, receives a universally bad press from Parliamentarian writers. In part this seems to have been because his morals did not match up to godly expectations, but his military performance certainly left much to be desired. By the autumn of 1643, Beeston Castle was being used as a supply depot, possibly as an armoury [5], and as a safe deposit for the valuables of a number of the Parliamentarian gentry of the area. The garrison had been reduced to about 60 men, probably members of the local Trained Band.

This peaceful interlude came to an abrupt end in November with the landing in North Wales of English veterans from Ireland, brought over in support of King Charles, and the appointment ot Lord John Byron to command the new armv formed around them, tasked with restoring the Royalist position in Cheshire, and capturing the Parliamentarian headquarters at Nantwich.

As a first step in this campaign, it was obviously important to secure Beeston Castle, a potentially formidable task, especially when time was short. On the night of December 12th/13th, a Royalist lorce, evidently consisting of some of Colonel Francis Gamull's Chester Regiment of Foot, and a company of firelocks from Ireland under the lire-eating Captain Thomas Sandford, appeared before Beeston.

Exactly what happened next is still the subject of some debate. It seems that Gamull and the bulk of the Royalist force staged some sort of demonstration before the Outer Gate. Steele appears to have drawn virtually all of His men down to meet this threat, leaving the way clear for Sandford and eight of his firelocks to gain entry to the Castle and occupy the dominating Inner Ward. It is usually presumed that they achieved this feat by scaling the north face of the crag, which was generally regarded as impregnable, and the curtain wall at this point consequently low, and so getting into the Inner Ward.

However, no contemporary account actually says that this happened, and, although a theoretically feasible route has been traced, [6] there must be some question whether a party of troops, encumbered with firelocks and other equipment, could actually have undertaken such a climb in pitch darkness ("between moonset and dawn"). The Cheshire Royalist, Randle Holme, wrote: "Colonel Gamull with the assistance ol Captain Sandford and his firelocks, in the middle of a dark night, surprised the innermost ward of Beeston Castle and garrisoned it for the King." [7] A Parliamentarian version states simply that Sandford and his men gained entrance to the Castle "by a bye way through treachery, as is supposed. [8] The fullest Royalist account, in the propaganda sheet, "Mercurius Aulicus", which might have been expected to wax eloquent on such a dramatic mountaineering feat, also makes no such suggestion, saving that on the night of December 12th: "Lord Byron sent out the firelocks and about 200 commanded musketeers to Beeston Castle .... and having two men to be their guide that had formerly been very conversant in the Castle, assaulted the outer ward, and presently forced the entrance, after that they fell upon the river ward [sic; probably an error for "inner ward", as there is no river anywhere near the Castle!] (where the greater part of their provision and all their ammunition was stored up) and very courageously soone made themselves masters of it, we caused the Rebells to betake themselves to the severall Towers of the Castle, where having little provision and no Ammunition, they desired a treaty, which was presently granted, wherein it was concluded that they should march away with such baggage as did properly belong to the soldiers, leaving all the Ordnance and ammunition behind them with all plate and other goods layd up in that Castle, which was the place wherein the Rebels of that County chiefly confided." [9]

A possible scenario is that Sandford and his men approached the Outer Ward on its northern side, where the slope of the hill, though steep enough to have resulted in the wall being less formidable than elsewhere, was still relatively easy to climb. They encountered few if any defenders, slipped in, possibly via the sally port which is known to have existed at some point in the outer walls, and made their way undetected to the entrance to the Inner Ward. This may in fact have been deserted, for Lancaster says that "there was nothing there but stones and a good prospect." [10]

Apparently threatened with imminent assault on the Outer Gateway, and with Sandford loose in his rear, Steele, understandably given his inexperience, lost his nerve and surrendered. He might have been forgiven this, but now made a fatal error by entertaining Sandford to dinner in his quarters in the Outer Gateway, and sending up a supply of beer to the firelocks in the Inner Ward. For the Cheshire Parliamentarian leadership, alarmed by the loss of Beeston, and doubtless infuriated by the capture of their valuables, this was the final insult; Steele, accused of treachery, was imprisoned on reaching Nantwich, courtmartialled, and shot.

ROYALIST BEESTON

It is possible that Captain Sandford was appointed briefly as First Royalist Governor of Beeston [11], but his tenure was short, as he was killed on January 18th in Byron's abortive assault on Nantwich. The only Royalist Governor so far definitely identified is Captain William Vallett, who held the command by April 1645, though the date oi his appointment is unknown. Vallett was evidently a professional soldier, who had served in Byron's Regiment of Horse [12]. The composition of the garrison is unclear; it may be assumed to have varied in strength according to circumstances. There is some slight evidence (see below) to suggest that in the spring of 1645 at least, the defenders of Beeston included soldiers claimed by the Parliamentarians to be "native Irish. Such claims are always to be treated with caution, but could mean that some of Byron's own Regiment of Foot, part raised in Ireland, were present.

Archeological work has produced considerable evidence of Royalist efforts to strengthen Beeston's defences. [13] It seems likely that the Royalist Governor, doubtless remembering the experience of the unfortunate Steele, established his private quarters in the South West Tower of the Inner Ward, whose fortifications were further strengthened and improved. It was probably after the Royalist takeover that the arrow-loops in the Hanking towers of the Inner Gatehouse were partially blocked to convert them into musket loopholes. To the south oi the East Tower is a blocked opening, which was probably a gunport, and a second one has been identified between the South East Tower and the East Gatehouse Tower, though there is no evidence that any ordnance was ever mounted. Surviving artifacts suggest that the South East Tower may have been used as an equipment store, whilst fragments ot lead shot moulds have been found in the South West Tower.

Undoubtedly, the Outer Ward will have remained the main centre of activity, containing timber barracks, storehouses and stables, and providing housing for other livestock, including sheep and cattle. In at least two of the towers, arrow slits were widened to permit the use of muskets, and a large number of military artifacts found in and around the Outer Gatehouse (see Appendix) suggest intensive use.

Beeston remained m largely undisturbed Royalist possession until the late autumn of 1644, when Byron's defeat at Montgomery, and the fall of Liverpool, enabled Brereton to resume operations against the main Royalist stronghold of Chester. The capture, or at least neutralisation, of Beeston, which was important both as an observation post and a base for Royalist cavalry raids into enemy territory, was a major Parliamentarian objective.

Back to English Civil War Times No. 51 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com