The ladle was given some prominence

in contemporary literature. At its simplest it

was like an elongated grocer's scoop,

constructed of sheet copper or an alloy, bent

round a former and fitted to a stave. The use

of non-ferrous metals minimised the

possibility of a spark being struck during

loading. The capacity of the ladle was usually

calculated in terms of volume, using the shot

diameter as a unit of measure. If the ladle were

not to be uncomfortably large, the load was

divided by two and the ladle used twice to

charge the gun. This technique meant that a

powder barrel had to be kept close at hand

during firing. The use of a 'budge' barrel, with a

leather cover and drawstring, or other method

of closure, helped to prevent fire reaching its

contents (figure 1).

(2)

During the late sixteenth and early

seventeenth centuries many ladies were

supplied to forces by the Ordnance Office at

the Tower. Very often materials such as

copper plate were furnished by merchants, for

example Edward Fawconer, Richard Cockyn

(or Cockaine), Robert Evelyn or Nicholas

Blaque, and the pieces were finished and

staved by Ordnance employees, contractors

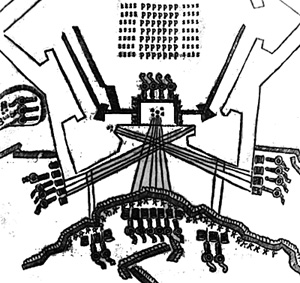

or London Pikemakers (Figure 2).

(3)

The many difficulties of loading with

the ladle are readily apparent. In the heat of

battle, the measures obtained are not likely to

have been any more exact than numbers of

heaped spoonfuls. Henry Hexam helpfully

suggested a 'little jog (to the ladle) that the

surplus may fall down again into the barrell'.

Thomas Smith favoured a brisk tap with a

ruler. (4)

Another drawback was the slowness

of the method. Using the ladle two or more

times took longer and, of course, a whole

barrel of powder had to be moved about.

Lastly, and most importantly, ladle loading

was highly dangerous. Loose powder could

fall to the ground or onto a wooden deck and

be ignited by flash embers, dust could rise

from the powder, and additionally, the

gunner's burning match was a danger both to

the ladle and to the barrel of powder. The

matchlocks; of the infantry and enemy action

could double the problem. Walking back and

forth with an open powder barrel cannot have

been pleasant at the best of times, but in

action it was tantamount to suicide. On a ship

it is very difficult to see how this method could have worked at all.

William Bourne summed up the difficulties of the ladle in his 'Shooting in great

ordnance'.

Spilt powder could result in the 'spoyling of men' and, in short, there was no worse lading or charging of Ordnance than with a ladell'.

(5)

It would therefore seem obvious that

the use of cartridges - sewn or glued bags of

paper, linen or canvas - was a highly practical

solution (Figure 3). Contemporary manuals

seem remarkably consistent on this point. As

Peter Whitehorne observed:

(6)

This sort of advice was repeated

frequently during the next century and most

authorities agreed that the cartridge was the

best method of loading, particularly in action.

Instructions

Every manual gave instructions for the

making of cartridges. Amongst the most

important English examples were Bourne's

'Art of shooting in great ordnance', 1587,

Lucar's version of 'Tartaglia', 1558, Thomas

Smith's 'Art of gunnery, 1600 and William

Eldred's 'Gunners glasse', 1646 (Figure 4).

Nathaniel Nye in his 'Art of gunnery'

described the making of cartridges in the

following terms:

(7)

Paper cartridges could be made in a

similar fashion, but in this case the former

was first smeared with tallow to prevent

sticking and the scams were glued.

(8)

Parallel examples for cartridge

manufacture can be found in every major

European language. Diego Ufano's celebrated

'Trato de Artilleria' clearly illustrates the

point. The original edition, in Spanish, was

published in Brussels in 1613. Here the reader

was informed of the making of 'el cartucho'

and how handy a way this was to charge

ordnance. In the French edition of 1621, the

cartridge translates to 'patron' and 'sachets', In

the German editions these became 'Secklein

oder patronen'. In Norton's 'The Gunner', the

diagrams by De Bry for the continental

editions of Ufano were pirated and put

straight into an English text - noted as 'cartridges'.

(9)

The Italians similarly were not left out as

many of their texts also mention cartridges.

The best example was perhaps Luigi Collado's

'Pratica nianuale'.

(10)

All of this goes to show that the

making of cartridges was common knowledge.

Proof that they were actually used on a

regular basis is more difficult to establish,

although some archaeological evidence, such as

the presence of reamers aboard the 'Mary

Rose' makes this seem likely.

(11)

It is noticeable, however, that

cartridges were not a central issue store. In

England, prior to the Civil War, it was not

usual to find cartridges sent from the

Ordnance Office at the Towers to ships and

garrisons in the same way as guns and barrels

of powder. Furthermore, there is evidence to

suppose that it was the duty of individual

gunners to make up their own cartridges, as

Eldred says ,at spare times ... in garrisons or

other places'.

This was similarly true of ship's

gunners, as is suggested by Richard Hawkins

in his 'Observations', where he relates the loss

of his ship 'Dainty' in action with the

Spaniards. He blames the master gunner,

(12)

This may be exaggerated, but clearly

cartridges were the norm and it was the

gunner's duty to make them.

Best Evidence

The best evidence that cartridges were

used as a matter of course is in the supply of

materials for their construction, and in

'remains', or lists of stores returned after

voyages. We have many excellent examples of

the provision of cartridge-making materials to

the ships of the Elizabethan navy. When the

'Hoape' was fitted out in 1572, cartridge

formers featured in its stores. In 1572 the lists

for the 'Swallow' mentioned not only formers,

but 'canvas for cartouches xx elles' and three

reams of ,royal paper'. In 1597 Richard Ascue,

purser of the 'Warspite', delivered 57 yards of

canvas to the master gunner William Bull at a

cost of 71s 3d. We can trace many similar

deliveries, explicitly for cartridge-making

purposes. (13)

In the 'Book of the Remaynes' taken in 1595 and 1596 for returning Royal Navy vessels, every ship has been provided with cartridgemaking materials, most of which had been

expanded by the time the fleet returned. (14)

The records are yet more specific for

the early Stuart navy. The fleet which went to

Cadiz in 1625, set out with formers, canvas,

Paper Royal, glue and thread amongst the

gunnery stores. When the ship returned the

clerks of the Ordnance were able to enumerate

the finished cartridges aboard. In the fleet of

1639, the minutely detailed account shows

that the cartridges were made up early in the

voyage, and that much powder was wasted in

the process especially if the cartridges were

emptied again at a later stage. However, it is

possible that a certain percentage was

accepted as a perk of the job.

(15)

We have similar information on land

garrisons, if not so complete or organised.

Cartridge -making equipment was sometimes

supplied and gunners sometimes petitioned

for more. This was the case in 1629, when one

of the gunners at Dover wrote to Lord Zouch,

Warden of the Cinque ports, requesting a

multitude of supplies including - 'Royall

Paper to make carthridges withall'.

(16)

Even if the Ordnance Office did not

actually supply the finished cartridge, it

certainly provided materials and the

inventories Suggest there was usually quite a

lot in store. In 1559 stocktaking revealed 125

years of canvas for cartridges and ten reams of

Paper Royal. The 1635 list shows not only

materials, but over 600 formers. Every

inventory of the sixteenth and seventeenth

century shows some provision for cartridge

manufacture.

(17)

Evidence relating to field armies also

reveals plenty of cartridge making material

In 1620-1 an expedition was planned to go to

the aid of the Elector Palatine. Equipment

included 'canvas for cartouches 1000 elles at

6d the ell' - no less than three quarters of a

mile of cartridge- making canvas. In 1627 an

expedition to the Isle dc Rhe took with it at

least five hundred yards of canvas and two

tons of cartridge paper. We should not

imagine that these stores were intended for

any other purposes, for there were plentiful

supplies of writing paper and canvas sandbags

over and above the provisions for cartridges.

(18)

During the Civil War cartridges were

carried along with the field guns. The Scottish

gunner and theorist Thomas Binning suggested

a universal scale of issue of 24 cartridges per

gun, of which half were to be filled and ready

for use at all times. A number of entries in

Roys 'Royalist Ordnance Papers' suggest this

was the sort of high standard which they

wanted to attain.

(19)

The case of the New Model Army is

particularly interesting, as this body was

provided not only with cartridge- making

materials but, unusually, with finished

cartridges as well as with cartridges cut out of

cloth but not sewn. This may give us a date at

which cartridges began to be considered an

issue item, rather than something which it was

the duty of individual gunners to make up. No

doubt this was made possible by the greater

standardisation of armament in the New

Model Army, in which field pieces of 31b and

61b were normal. In earlier times, when guns

were much more individually styled, it was

not worthwhile considering the cartridge as an

issue store, because so many different types

were required.

One of the largest orders for finished

cartridges was contracted on 10 January 1646

with Nathaniel Hunifreys and Richard

Bradley for 1,000, at ten pence a pecce ...

ready money'. It was highly unusual that

ready money be either asked for, or given, on

a government contract and this may be a

measure of the importance placed on the

supply of cartridges.

(20)

Such strong evidence can only suggest

that the cartridge was the normal method of

loading used from the early sixteenth century

onwards. The ladle in the manuals and in

archaeological finds requires sonic

reinterpretation. Two possible explanations

may reasonably be put forward.

First, it was an added security. If the

cartridges were insufficient in number, or

damp, or lost, the gunner could have resorted

to the ladle for loose powder as an emergency

measure. It is even possible that the ladle

could have been used for the quick insertion of

the cartridge. Second, in ceremonial or

practice firing, speed was not important. It

was the quality of the show that mattered. In

such circumstances few gunners would have

bothered with the expense of a cartridge. We

have therefore the highly-choreographed

descriptions of the use of the ladle - handled as Eldred said like 'an artist'.

(1)

See for example 0 F G Hogg, 'English Artillery' Woolwich, 1963, p.45; H W 1, Hime, 'Gunpowder and Ammunition', London, 1904, p.235.

Norton's "Gunner" (circa 1628) Illustrations.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Despite the amount of interest in early

modern artillery, particularly that aroused by

nautical archaeology, there are many areas of

gunnery technique which have yet to receive

detailed examination. Loading is perhaps the

most vital of these. Several authorities have

assumed that the process of loading was

necessarily slow, usually being carried out

with the use of the ladle.

(1)

Despite the amount of interest in early

modern artillery, particularly that aroused by

nautical archaeology, there are many areas of

gunnery technique which have yet to receive

detailed examination. Loading is perhaps the

most vital of these. Several authorities have

assumed that the process of loading was

necessarily slow, usually being carried out

with the use of the ladle.

(1)

'The ladell shall have some tyme more

powder, and sometyme less powder, by a

good quantitye, and especially if that hee

clothe it hastely as in time of service it

alwayes requireth haste.'

'For the more speedie shooting of

ordinance, the iuste charge in pouder of everye

peece may aforhand be prepared in a

readinesse and put in bagges of linnen or in

great papers made for the same purpose,

which in a sodaine may be chapt into the

mouth of a peece with the holler thereof

thrust after, as farre as they will goe, and then

thrusting a long wyer into the touchehole with

some pouder so soone as it is leveled, it may

incontinent be shot of: which maner of

charging is done most quikely and a great deale

sooner than any other wave, and when haste

requires very needfull.'

'take canvas, such as the powder will

not creep thorow, and let it be in breadth ...

just three diameters of the peece ... and for

the length you will find it by the filling of

them, these being sewed together upon a

mould; which must be a very little lesse than

the diameter of the bore, and about 4

diameters long.'

'For bearing me ever in hand, that he

had five hundred cartreges in a readinesse,

within one hours fight we were forced to

occupie three persons, only in making and

filling cartreges, and of five hundreth Elles of

canvas and other cloth given him for that

purpose, at sundry times, not one yard was

to be found.'

NOTES

(2) See R Norton, 'The Gunner', London, 1628, pp. 42-3, and folding plates.

(3) Public Record Office, War Office papers 54/3; 6; 7; 8; 9; 11.

(4)H Hexam, 'The Principles of the Art Militarie',

The Hague, 1640, Part III, pl.3; Thomas Smith, 'The Art of Gunnery', London, 1600, p.8 1.

(5)W Bourne, 'The Art of Shooting in Great Ordnance', London, 1587, pp.30-1.

(6) P Whitehorne, 'Certain Wayes for the Ordering of Souldiers in Battelray', London, 1573, p.33v.

(7) W Nye, 'The Art of Gunnery', London, 1647,

p.42.

(8)See Roberts, 'Compleate Cannoniere', London,

1639, p.29.

(9) D Ufano, 'Trato de Artilleria', Brussels, 1613,

p.306; 'Artillerie C'est a Dire' Zutphen, 1621; 'Archeley', Frankfurt, 1614.

(10) L Collaclo, 'Pratica Manuale Di Arteglieria', Venice, 1586.

(11) The "reamer" or priming iron was a sharp spike or wire to clear the touch hole and pierce the skin of the cartridge.

(12) 'The Observations of Sir Richard Hawkins Knight, in his 'Voiage to the South Sea Anno Dom 1593', London, 1622, p. 127. An "Ell" was a unit of meaure equalling 1.25 yards in English usage. (A Scottish "Ell" was 37.2 in; the Flemish "Ell" 27 in.)

(13) British Library Additional NIS 5752 f36; PRO WO 52/2. "Paper Roval" probably meant initially any large sheet. In the printing trade it was later 25 in. by 20 in. The term is known to have been in use from the late fifteenth century.

(14) National Maritime Museum NIS CAD C/I; ADL/H/14; PLA/PI 1; PRO WO 55/1627.

(15) PRO WO 49/110; 55/1601.

(16) British Library Egerton MS 2584, t362.

(17) PRO WO 55/1672; 55/1690; State Papers 12/6 etc. See also H L. Blackmore, 'The Armouries of the Tower of London'. Vol I Ordnance, London, 1976, pp. 251-389.

(18) British Library Harleian NIS 5109. Royal Artillery

Institution MD 979 "Inventory of the Equipment of the Artillery Embarked", 1627.

(19) I. Roy, 'The Royalist Ordnance Papers',

Oxfordshire Record Society, 2 Vols 1964 and 1976, passim. T Binning, 'Light to the Art of

Gunnery', Edinburgh 1676, p. 109.

(20) Museum of London MS 46-78/709. See also G I Mungeam,

"Contracts for the Supply of Equipment to the New Model" 'Journal of the Arms and Armour Society', Vol VI, part 3, 1967.

Back to English Civil War Times No. 45 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by Partizan Press

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com