The "Trot of Turriff" as it was known for obvious reasons is important to history only as being the first real battle of the Civil War and has little to offer the military historian save an admirable example of how not to conduct military operations.

The battle was a very straightforward affair which may be briefly described by the statement that the Royalists ran towards the village of Turriff and the Covenanters ran away from it! But the circumstances surrounding the encounter were from beginning to end pure comic opera and the story well worth telling.

In Scotland as in England there was at first some considerable reluctance on the part of either faction to tranalate rhetoric into cold-blooded action though preparations for an armed conflict went on apace. Shortly before his arrest by Montrose (deepite the protection of a 'safe-conduct') the Marquis of Huntly, the Royalist leader, had received a considerable quantity of arms from the King much to the alarm of the local Covenanters and as soon as he was incarcerated in Edinburgh Castle, they spared no time in confiscating such of the arms as could be found.

A quantity of the sequestered materiel was secured in Towie Barclay Castle near Turriff and on the 10th of May a party of Royalist Gentry and their servants made a noisy but ineffectual attempt to sieze the castle and recapture the arms. What set this miserable affair apart from numerous other similar affrays taking place at the time was the death of one of the Royalists, shot by a Covenanter. Taking this to be the signal for a general conflagration, the gentry of both sides called their followers together, the Royalists at Strathbogie and the Covenanters at Turriff, though at first neither party was willing to go further.

The Royalists, mindful of a previous visitation by large numbers of Covenanting trooys from the south were not unaware that they ought to act quickly, but with Huntly a prisoner and his eldest son, the Earl of Aboyne in England, they lacked a leader. Therefore the whole of the 13th of May was spent in trying to decide who amonst them were fittest to 1ead their small army. Some unanimity was quickly established that the ablest was in fact a gentleman named Ogilvy, but it was nontheless felt to be unnacceptable by most of the gentry, who belonging to the great house of Gordon refused to countenance any but a Cordon leading them.

At length they compromised on a dual command by which time it was dusk and having wasted all day in deciding who was in charge, they then proceeded to spend all night in discussing whether they actually had the authority to fight anybody in the first place.

Thoroughly exasperated however one of their number roundly declared that it would be better in this instance to fight first and then justify themselves afterwarde and content with this sensible advice, the Royalist arny at last took the road for Turriff.

To Turriff

Deficient though it may have been in senior officers this, the first of the Royalist armies was a compact, well-equipped force comprising two Troop of Horse armed with carbines, pistols, swords, buff-coats and in many cases corsettes as well. Five or six Companies of the Strathbogie Regiment, a regular unit "all new levied souldiours, who Huntly had caused train" now led by a professional soldier, Lieutenent Colonel William Johnston, two thirds of the men being musketeers and the remainder pikemen - most of them boasting corsettes and four brass cannon of uncertain vintage. The Covenanters they intended to beat were equally strong but had not yet attempted to organize themselves properly and certainly had nothing capable of facing up to Huntly's Foot, raw though they were.

Marching all night the Royalists approached Turriff just before daybreak but at this point one of their cannon broke down and to Johnston's deepir a halt was called while the gunners went in search of a carpenter, one at length being found the gun was "patched up as well as time wold permitt" and the rather shaky blitzkrieg lurched onwards once more.

To make matters worse it would mean that a Covenanting picket had both seen and listened to the whole incredible episode but as if to prove that the Royalists had no monopoly on incompetance that morning they talked amongst themselves about but no-one thought of informing anyone in the village.

Thus it was daylight before the Covenanters realized that they were about to be attacked - and then they pannicked for they too lacked a recognieed 1eader so that in the words of one chronicler "all commanded and none obeyed.." Meanwhile, Johnston, thoroughly disguated by his amateur superiors had siezed command of the Royalist artillery, seeing that the enemy were in some difficulties, he took advantage of their confusion to fetch a compass about the village in order to attack it from the more open eastern side. This induced an even greater panic in the Covenanters for they had only barricaded the Strathbogie road at the north-western end of the village and frantic efforts were made to build another while Johnston drew up his men.

The Battle

Two of the Royalist cannon were fired, seemingly too high, but to the Covenenters frightening enough, a third cannonball went through the gable end of the house but the destination of the fourth must remain a mystery since the carraige colapsed as it was being fired--Suggesting the carpenter had not been too successful.

The brief cannonade was too much for the Covenanters, who cravenly abandoned their half-finished barricade and ran down the street. Suitably encouraged by this sight, the Royalist Foot "could not, by their commanders, be restrained from a present charge upon their enemies" and after succeeding in shooting one of their own men in the back, secured the eastern end of the village.

Whilst the musketeers burst into the houses and gardens, the pikemen tore down the barricade and the Horse poured in. For the Covenanters, this was thefinal straw, and rushing out of the village, they bolted in all directions.

Feeling suitably pleased with themselves, the Royalists did not bother to follow them, though to be fair, the fugitives were so broken and scattered that a pursuit would have been pointless. Nevertheless, having quite literally beaten the King's enemies before breakfast, the Royalists found themselves at something of a lose end until someone remembered the unfortunate who had earlier been shot in the back. It was resolved to give him a proper military funeral, for he had been the only man killed on either side. As one might expect, even this was botched, and what occured is best described by James Gordon in his "History of the Scots Affairs."

-

"one common soldier killed...whom the Gordons caused burye solemly that day, out of ane idle vaunte, in the buriell place of Walter Barclay of Towie, within the churche of Turreffe: not without great terror to the miinister of the place, Mr. Thomas Michell, who all the whyle with his sonne, disgwysed in a woman's habit, had gott upp and was lurking above the syling of the churche, and whilst the soldiers wer discharging volleyse of shotte within the churche and piercing the syling with their bullets in severall places."

Sources

James Gordon: History of the Scots Affairs, Spalding Club, 1841

Patrick Gordon: Britaines Distemper, Spalding Club, 1844

John Spalding: Memorialls of the Trubles in Scotland, Spalding Club, 1850-51

Stuart Reid: Scots Armies of the Civil War, Partizan Press, 1982

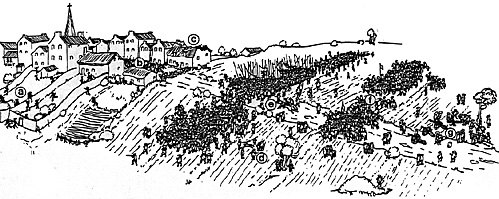

Battle Map

A (lower left): Covenanters flee out of Village

B (left, edge of town): Affrighted by cannon, the Covenanters abandon the barricade.

C (top middle): A House struck by cannon ball

D (low middle): Common Soldier slain by his own comrades

E (middle): Marquis of Huntley's Strathbogie regt.

F (right): Two troops of Horse

G (lower right): Four brass cannon, one sadly broken in firing it.

Back to English Civil War Notes&Queries No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com