Part 1: Birmingham

Part 1: Birmingham

By the Spring of 1643, Charles I was in such need of gunpowder, that his forthcoming campaign rested largely upon the Queen being able to bring over supplies from the Continent. That she did, landing at Bridlington in February, with Officers, arms for 10,O00 men and the vital powder, as well as ordnance.

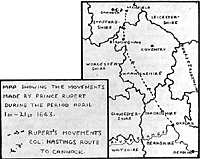

Large Map (85K)

However, while the King and his army were in Oxford, the Queen and the munitions were with the Earl of Newcastle in York. The road between them was so heavily infested with Parliamentarian garrisons and sypathizers that even "the most private messengers travelled with great hazard, three being intercepted for (every) one that escaped.."

If, as was the case, the most innocent looking messengers could not get to or from the King, then a large convoy of powder would need "nothing lese than an army" to get it through. To this end, Prince Rupert volunteered to go north with a small force. He convinced his uncle that he could seize Lichfleld (from where many of the enemy outposts along the proposed route drew their strength), before entering Yorkshire. There he would join the Queen and then escort her,

"if she were ready," and the munitions back to Oxford.

The force that left the Royal Capital waa chosen for speed, being largely comprised of Horse and Dragoons. There were 1,200 of the former and an unspecified number of the latter.

Besides these, there were 6-700 Foote, many of whom were armed with little more than farm tools and clubs. There was also have been up to 6 light guns, the largest being a 2,500 LB

Saker, firing a 5.25 LB shot.

The main route north to Lichfleld ran through Birmingham, "....a town so generally wicked that it had risen upon small parties of the King's (men), and killed or taken them prisoners

and sent them to Coventry, declaring a more peremptory malice to his Majesty than any other place."

If this were not enough, the inhabitants readily supplied Parliament with Swords (for which the town was renowned) and other weapons but refused such service for the King.

Armed and ready as the town was, supported by Colonel Richard Graves with 14O musketeers and some horse from Lichfield, it did not deter Rupert.

"His Highness, hardly believing it possible that when they should discover his power they would offer to make resistance, and being unwilling to receive interruption in his more

important design, sent his Quartermasters thither to take up his lodging and to assure then that if they behaved themselves peaceably, they should not suffer for what was past.."

The people of the Town were in no trusting mood though. Their response was to pour shot upon the Quartermasters. Indeed, a Noble action in the name of Parliament but foolhardy nonetheless, for Birmingham was not a walled City such as York. The point was emphasized by tbe fact that Rupert, as he stood before the Town on that Easter Friday, 3rd April, could see that "they (had) cast up little slight worke at both ends of the Town, and barricadad the rest."

Behind the works stood thatched cottages, an inviting target indeed. They were quickly fired, the defenders, being not able to "contend with both enemies," fled back from the works. As the Royalists pursued them were counter-attacked by the Horse.

Though quickly swept away by sheer numbers, they left their mark. "In tbe entrance of this town, and in the too eager pursuit of that loose troop of horse that was in it, the earl

of Denbigh...was unfortunately wounded with many hurte to the head and body with swords and poleaxes."

The Earl died five days later after having been overthrown in his coach by a careless coachman.

The storming of Birmingham had not taken long. Royalist casualties were light, as were those of the defenders, whose flight had been covered by the thick smoke from the burning

houses. Among those who fell was the Rev. Whitehall, military as well ae Spiritual leader of the citizens. "...he had not only refused quarter but provoked the soldier by the most

odious revilings and reproaches of the person and honour of the King that can be imagined....."

Besides being quite a fanatic, it was proved by letters found on him that Whitehall lusted after the pleasures of the flesh. Probably because of this, Parliament claimed he had nothing to do with the loca1 Leadership, being nothing more than an escaped Lunatic!

As to the burning of the Cottages, both sides blamed each other but there can be no doubt it was the Royalists. For they had the the most to gain--Birmingham itself. The Royalists claimed later that they had tried to quench the flames.

As well as costing Rupert an admonishment from the King, it lost him valuable time in which Craves and most of his men were able to reach, and alert, Lichfield, the main objective.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.Birmingham

Back to English Civil War Notes&Queries No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by Partizan Press

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com