This is the first of a two-part series on the various mounted units that made up the Ottoman army of the Napoleonic era. In part one we will look at those units that were at least nominally under the control of the central state. In our next installment we will look at the troops under the control of the provincial governors.

SUVARILERI

The Capou-Koulis cavalry was militarily more importent and had higher prestige than the infantry. It was known as the Suvarileri or Boluk Halki (regiment men) and numbered about 28,000 men.

Ar right, an army command group consisting of from left to right, the Grand Vezir's pipebearer, the Grand Vezir, an officer of Janissaries, a Tartar courier and a Mamluk officer.

Ar right, an army command group consisting of from left to right, the Grand Vezir's pipebearer, the Grand Vezir, an officer of Janissaries, a Tartar courier and a Mamluk officer.

Only about a third of this total were actual members of the force. The rest were slaves owned by the corps members. Each man had to train and take on campaign a given number of armed and mounted slaves, maintained at his own expense.

This force was composed of six divisions, two of which were considered guard cavalry. One guard unit was known as the Silahdar (weapons bearers) and had originally been the Sultan's personal guard. By the time of Sultan Selim III, this duty had been taken over by the Suvarileri's newest unit, the elite Sipahi Oglans (Sipahi's children).

Both units were armored, lance-armed, heavy cavalry. The Silahdar numbered about 8,000 horsemen and the Sipahi Oglans about 10,000. In addition to his other duties, the commander of the Silahdar served as swordbearer to the Sultan.

The other units were the left and right Ulufecijan (salaried men) and the left and right Gureba (strangers, so called because they were originally Muslim mercenaries drawn from other parts of the empire). The designation left and right referred to the positions the units would traditionally take in the line of battle.

Not as heavily armored as the two guard units, these units were all medium cavalry. Each numbered about 2,000 men. Administratively these units were grouped under the guard cavalry with the units of the right under the Silahdar and the units of the left under the Sipahi Oglans. Each trooper was equipped as he saw fit, though most were armored, usually wearing his robes over chain mail, and armed with swords, lances, pistols and javelins.

The banners of the Sipahi Oglans and Silahdar were both pennant shaped and marked with two silver crescents. The Sipahi Oglans banner was red and that of the Silahdar was yellow.

The Banners of the Ulufecijan units were square shaped and were red and yellow and yellow and white striped (though some sources list them as red-and-white and red-and-yellow). The flags of the Gurebas were also square and were decorated with green and white horizontal stripes.

The number of armed slaves maintained by each man was proportionate to the scale at which he was paid. The members of the Sipahi Oglans, the highest paid unit, were expected to maintain five or six, the members of the Silahdar, four or five, the members of the Ulufecijan only two or three and the members of the Gurebas. the least well paid, were under no obligation to maintain any slaves at all.

Each division was commanded by an Agha appointed from the Imperial Household, who was assisted by four other general officers and one or more secretaries. Within the units the men were organized into squadrons of 20, each commanded by a Boluk Bashi and sub officers.

Unlike the Janissaries, the cavalry were not provided with barracks. Instead, most lived in villages near the capital in order to use the local pastures for their horses. Only the Agha and other general officers of each division had quarters in the capital.

The men of the Suvarileri were noted for the magnificence of their dress and accoutrements, which put those of the Janissaries and feudal cavalry in the shade.

In addition to these traditional forces, Sultan Selim raised a body of 10,000 Sipahis, known as the Sipahis of the Porte, which were maintained under salary at the capital. This force of lance-armed light cavalry was barracked in Istanbul and received regular training.

At right, shown above is an Ottoman Imperial cavalry soldier of the Napoleonic era. The illustration on which it is based is labeled only as "Heavy Cavalry." In all probability the picture shows a member of the Suvarileri. In battle most of his armor would have been hidden under his robes.

At right, shown above is an Ottoman Imperial cavalry soldier of the Napoleonic era. The illustration on which it is based is labeled only as "Heavy Cavalry." In all probability the picture shows a member of the Suvarileri. In battle most of his armor would have been hidden under his robes.

A number of smaller units were also attached to the Imperial Household.

These included the Sultan's Mounted Life Guards (the Muteferrik), a mounted force of about 500 made up of the sons of prominent soldiers and the relatives of tributary rulers. They were highly paid and magnificently accoutred, each owning a number of armed slave retainers. The term Muteferrika, which means 'separated,' is believed to have been applied to the members of this unit because they were employed on special duties. The unit underwent extensive training in European cavalry tactics by French advisers during Selim's reign.

The Sultan's guard also included several small units: the elite Djellis, the Gonullu and the Lifewatch Guides, each numbering about 100 men. It was the job of the Lifewatch Guard to escort the commander-in-chief while on campaign.

Other cavalry units stationed in or around the capital included the Mamluks of the Grand Vezir, about 100 men, the Mamluks of the Grand Signor, about 100 men, and the Mamluks of Istanbul, about 500 men. These Mamluk units should not be confused with the Egyptian cavalry force of the same name, but were instead lance-armed light cavalry.

At the time of the destruction of the Janissaries in 1826 the entire Imperial cavalry force was disbanded and replaced by a new European-style cavalry.

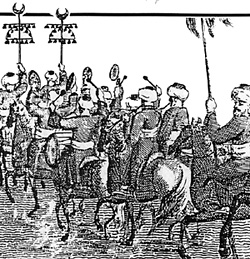

This drawing and the illustration at the beginning of this article are both details from a much larger work by E. Dayes entitled "The March of the Grand Vezir's Army Across the Desert," which served as the frontice piece of Dr. William Wittman s book "Travels in Turkey, Asia-Minor, Syria and Across the Desert into Egypt During the Years 1799, 1800, and 1801 in the Company of the Turkish Army." At right is a drawing of the Grand Vezir's mounted band.

This drawing and the illustration at the beginning of this article are both details from a much larger work by E. Dayes entitled "The March of the Grand Vezir's Army Across the Desert," which served as the frontice piece of Dr. William Wittman s book "Travels in Turkey, Asia-Minor, Syria and Across the Desert into Egypt During the Years 1799, 1800, and 1801 in the Company of the Turkish Army." At right is a drawing of the Grand Vezir's mounted band.

SIPAHIS

The majority of the Ottoman army was made up of cavalry and the majority of the cavalry was made up of the Sipahis (horsemen).

The Sipahis received no pay but were instead granted tracts of land known as Timars in exchange for their services. For this reason they are often compared with medieval European knights. This is not a totally accurate comparison, though, for the Sipahis did not own their lands but simply held them in trust. They also had only limited rights over the peasants on their lands, having to pay them for their work.

Each Sipahi had to be ready at any moment to call his men to arms in specified numbers. In the event of failure to do so, the Sipahi was deprived of his fief. To keep the force up to full strength, each district was required to maintain a pool of apprentices that was equal to 10 percent of its active Timar holders.

The conditions of service were not uniform for all Sipahi. Some were always obliged to obey the call to arms. These were known as Eskincis (from Esmek meaning 'to ride to war'). Others served in rotation and were known as Bi-nevbet, an Arabic word meaning 'in turn.'

The Sipahi were further divided by the wealth of the Timars. The largest Timars were known as Zaimets. The lowest class of Sipahi went on service unaccompanied, mounted, wearing a breastplate and bringing a tent.

Those that derived as much as twice the minimum yield of a Timar were obliged to bring with them a fully equipped and mounted man-at-arms known as a Cebeli (from the Persian word Coba, 'a coat of mail'). The larger the income of the fief, the more Cebeli that were required, with the largest Timars supplying a Sipahi and 15 Cebeli. Additionally, it was not uncommon for zealots to provide additional contingents of as many as 50 additional warriors.

The Timars could be inherited. If the Timar holder was honorably in active service and left heirs capable immediately taking over his position, this was allowed. If the Timar holder died of natural causes, his heirs could not inherit. If he left sons who were not of age, they could not inherit, but they were allowed to join the corps of apprentices and eventually earn the rights to a Timar on their own military merits.

Sipahi units, which numbered about 1,000 men each, were organized around geographical districts (Sanjaks).

At the highest level the Sipahis were organized under the provincial governors. The officers of the Sipahis below the governors were of three ranks.

The highest was the Alay-Bey. Each Alay-Bey was elected for a three-year term by the Timar holders in his district (Sanjak). It was his job to muster the Sipahi for campaign and provide direct field command of the unit. In exchange for this service he was granted the largest ot the Timars and provided with a standard and drum.

Below the Alay-Bey came the Ceri-Bashis (or subasis) who were chosen from among the largest Timar holders of each of the smaller administrative districts, called Kada (the area ruled by a Kadi, or judge). In times of peace the Ceri- Bashis performed the duties of police.

The third rank of officers were the Ceri-Surucus, who enrolled and policed the Sipahis when on campaign.

The Sipahis, which were administratively divided into 16 legions, were chiefly drawn from the Asian provinces. These Asian units rode horses which, while smaller than most European horses, were very hardy and full of fire and spirit.

At the time of Selim III, the empire numbered approximately 100,000 Timar holders. The force, though, had been allowed to deteriorate badly. Many Timars were held by individuals or local governors simply for their revenue with no one willing or able to perform the required military service.

It is estimated that the actual number of Sipahis who could be counted on to perform military duties numbered only about 40,000 to 60,000. To correct this Selim ordered all Timar holders to undergo at least six months' training every two years in Istanbul under the direction of European cavalry officers, mainly from France. In reality very few Timar holders accepted the training.

Another weakness of the Sipahi system which was exposed by the disastrous 1787-1792 war with Russia and Austria was the fact that the Sipahis, as land administrators, were only summer soldiers. Under the traditional feudal system it was necessary for them to return home each winter to collect the revenues they needed to maintain themselves and their troops in the Imperial army.

To correct this, Selim declared that it was no longer an absolute right for the Sipahis to return home each winter. Instead every 10 Sipahis in the army holding lands in the same or neighboring districts were allowed to choose one of their number to go home and administer the land for himself and the others.

After the overthrow of Selim in 1807 his reforms were overturned and the provincial Sipahis became merely a provincial militia cavalry, no longer even being called up to serve in the Imperial army.

As with other irregular troops of the Ottoman army, the Sipahis had no standard uniform, with each man being responsible for his own costume, horse and weapons. The Sipahis were usually armed with two swords. a pair of pistols, a musket and a lance with either a red or yellow pennant, the traditional distinctive mark of a Sipahi.

The dress of the Sipahis was both colorful and rich. The preferred colors were scarlet, red, violet, dark blue and green. Gold and silver thread were used extensively to highlight clothing. Caftans worn over armor often had Hussars-style lace fronts. Their trousers were baggy and their boots normally yellow. When turbans were worn, they were always white with a red or purple central cap. Cloaks were often worn.

In the field each Sipahi unit carried its own large banner. The first corps carried a yellow standard, the second a red one. The other Sipahi units carried red and white, white and yellow, green, or white standards. In addition to this "regimental" banner, the Sipahis also carried a tremendous mixture of smaller banners and flags into battle, with each unit and subdivision carrying its own banner, down to the troop level.

GARRISON TROOPS

The Ottomans placed heavy reliance on large, formidable fortresses to guard their European and Asian frontiers and many of the important passes within the Empire. When Selim III became Sultan he spent a great deal of effort upgrading and repairing the numerous fortresses throughout the empire. The cost of the garrisons and maintenance of these important fortresses was paid from local revenues set aside specifically for this purpose.

Originally all fortresses were garrisoned exclusively by Janissaries, but over time the fortresses came to have an independent organization of their own. While Janissary officers and, in some cases, a few troops, were still sent out from the capital to form the nucleus of such garrisons, they were by the time of Selim III maintained primarily by local troops. On paper these forces were made up primarily of Yamaks, but since these men, mostly local artisans, preferred to work at their trade in the cities, the fortresses came to be actually garrisoned by a new mercenary force.

This mercenary force was known collectively as the Serhadd-Koulis (slaves of the frontier) to distinguish them from the Capou-Koulis (slaves of the Porte). In Europe they were almost all drawn from Bosnia, Albania and Macedonia and totaled about 10,000 cavalry and 40,000 infantry. While the European Serhadd-Kouli enjoyed a fair reputation, the members of the Asian force were regarded as the worst soldiers in the Empire.

The troops within the Serhadd-Koulis were divided into three types of infantry (Azabs, Segmens and Muellems) and three types of cavalry (Gonullus, Beslis and Djellis). The Segmens and Muellems served as pioneers, being charged with the upkeep of roads and fortifications. The Azabs were regular infantry. The Gonullus were heavy cavalry, the Beslis light cavalry and the Djellis served as scouts.

Back to Dragoman Vol. 3 No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Dragoman List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by William E. Johnson

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com