For more than 400 years Bosnia was a frontier

province of the Ottoman Empire, providing the first line of

defense against the Austrians. Throughout the 18th and 19th

centuries it was often a battleground.

For more than 400 years Bosnia was a frontier

province of the Ottoman Empire, providing the first line of

defense against the Austrians. Throughout the 18th and 19th

centuries it was often a battleground.

At right, the Ghazi-Husrefbey Mosque in Sarejevo.

During the Napoleonic Era it was twice the scene of intense combat. During the War of 1789-1792 which opened the period, it was twice invaded by major Austrian armies, one of which penetrated as far as the borders of Herzegovina. During the War of 1806-1812 the provincial forces of Bosnia were again heavily engaged, this time against the Serbian rebels and their Russian allies with several major battles being fought along the Serbian border, along the Drina River line.

By the Napoleonic Era the Bosnians had become among the most conservative of all the Sultan's subjects in their opposition to reform and devotion to the law of the Prophet. For instance, in 1807 they refused to allow an allied French force to cross their land to attack the invading Russians who were then overrunning the Ottoman provinces of Wallachia and Moldavia. The local Beys felt both the French and the Russians were infidels and both needed to be resisted with all possible force.

Even after the destruction of the Janissaries in 1826, the Bosnian Beys refused to accept all attempts at modernization or reform and frequently rose in rebellion against the reforms of Sultan Mahmud II.

As with most Ottoman provinces, Bosnia was ruled by a Vezir appointed from Istanbul. However, in Bosnia, the real power was centered in the great Bosnian Beys who had gradually become hereditary headmen of the various divisions of the country.

Tracts of Land

Originally feudal warriors who had been granted Timars (tracks of land in exchange for military service), many of them had over the years, by hook or by crook, converted these Timars into quasi-hereditary estates. The most important of these local landed warriors come mended fortresses scattered around the region and ruled their local districts as all but independent princes. With their retainers, who often included Christians, they kept local order and defended their territories from Hapsburg raiders and brigands.

While some were hereditary, holding their estates for generation after generation, others continued to be appointed by the local Vezir and records show the Vezir occasionally transferring them from one fortress to another. These local Bosnian fortress commanders, usually bearing the title of Kapetan, were a major part of the local defense structure. During the Napoleonic Era there were about 38 great Kapetans, each with at least a thousand men or more under his direct command.

So strong was their power that they would only permit the governor appointed by Istanbul to remain in the main city of Sarajevo for 48 hours at a time. They also resisted all attempts to move the official capital to Sarajevo from the much smaller town of Travnik. The Beys ruled the province on feudal lines and were quite content with a system that allowed them to do as they pleased at home and provided them with the occasional luxury of plunder from forays abroad.

The regular military forces of Bosnia, under the command of the governor, consisted of the local Janissaries and their Yamak auxiliaries. During the Napoleonic Era there were approximately 16,000 enrolled in the Janissary Ortas stationed in Bosnia and a further 62,000 in the Yamaks; although as in other parts of the empire, the actual number which could be called upon in a crisis was much smaller. Over the years the Janissaries had increasingly become an hereditary caste with more interest in trade than in fighting. In Bosnia they were an especially turbulent group, often resisting the orders of their Agha (commander) who was sent from Istanbul.

In addition to these forces the governor had his private guard of both infantry and cavalry, usually made up of Albanians. At right, commander of the Vezir's Guard in 1730.

In addition to these forces the governor had his private guard of both infantry and cavalry, usually made up of Albanians. At right, commander of the Vezir's Guard in 1730.

As a result of the strength of the Beys, the Ottoman governor of Bosnia was in the habit of annually convening an all-Bosnia meeting with his Divan (advisory council). This included the Kapetans plus the important Ayans (landed nobles) and town leaders.

The Land and its People

Located in the heart of Europe (as the crow flies, Sarajevo is closer to Rome than is Milan), it was a beautiful land of picturesque mountain scenery, much of it covered by forests, with some coal and minerals.

Bosnia was one of the larger Ottoman provinces encompassing about 20,000 square miles (about the size of West Virginia; 1/4 larger than Switzerland). The province's traditional borders, established in the medieval period, were: the Sava River in the north, the Drina River in the east and southeast, and the Dinaric Alps in the west. Henegovina (the Duchy) was the historical name for the country's southwestern region (around the town of Mostar).

Under the Ottomans the province was further divided into four Sanjaks, or districts. These included Bosnia in the center administered from Sarajevo, Herzegovina in the south administered from Plevlja, and Zvornik in the east and Klis in the west bordering Dalmatia, both ruled from towns of the same name. These four Sanjaks were further divided into a total of 19 Kadiliks. The entire region was administered by a Vezir (Vali) who ruled from Travnik, the provincial capital.

By Balkan standards the land in Bosnia was very rich. From the Middle Ages on it enjoyed an export trade from its many mines, primarily lead and silver, with an especially rich silver mine near Srebrenica.

Besides the majority Muslims, Bosnia also had large groups of Catholics (in the north and west) and Orthodox Christians (in the south and east). Under the Ottoman Millet system, which divided the citizens of the empire into groups based on religion, both sets of Christians were under the Greek Orthodox patriarch in Istanbul who appointed local bishops and priests, drawn almost exclusively from the Greek community in Istanbul. These Greeks, most of whom spoke no Slavic, had purchased their offices and hoped to recoup their investment as rapidly and profitably as possible. There was also a small Jewish community, limited primarily to the major towns and cities.

Bosnia's towns and cities had always been the shared home of people from all ethnic and religious groups. This even included the Jews, many of whom had found a haven in the tolerant city of Sarajevo in 1492 following their expulsion from Spain. Unlike Jews in Venice and elsewhere in Europe, Sarajevo's Jews were not confined to a ghetto. The city's principal mosques, synagogues and Christian churches were all located in close proximity to each other, a visible sign of the intermingled public and private lives of its ethnic and religious communities.

Christians and Muslims

In Bosnia, more so than in most regions, the Christians and Muslims were especially close and friendly, with the Christians often volunteering to help repel attacks by the Christian Austrians.

In the countryside the main social organization of the people, for both Muslims and Christians, was oriented around family and kin. The Zadruga, a kin-based corporate group holding property in common, was the traditional basis of rural social organization. Its most common form was a group of related males, along with their spouses and children who owned and farmed land in common.

Bosnia's mountains, with narrow roads running through passes, encouraged highwaymen. Brigandage was endemic, especially in Herzegovina, from the beginning of recorded history. The people of Herzegovina, whose region included some of the poorest soil in Bosnia, tended to lead a pastoral existence, raising sheep and horses. As a result, they tended to migrate from the valIeys in the winter to the mountain pastures in the spring and summer. With their ready supply of horses they could often be hired to lead and guard merchant caravans passing through the region. This often put them into direct conflict with neighboring clans who made their living plundedng these same caravans.

Organized as extended families, these heavily- armed clans of Bosnians fielded large mounted units which plundered one another, fought over pasture lands and rented themselves out to local warlords.

A warlike people, the Bosnians were always eager to volunteer as mercenades, and served with distinction throughout the Ottoman Empire. As a result many clans gained special rights, such as the right to bear arms despite their nominal Christianity.

Bosnians were especially numerous in the Imperial cannon corps, with almost all Ottoman gunners drawn from Bosnia during the Napoleonic Era. Like most Ottomans, though, they preferred to serve as cavalrymen.

A British diplomat who traveled for several days with a Bosnian horseman in 1809 described him as wearing "a coat of mail under his clothes, and a burnished helmet on his head, and was armed with two heavy rifle guns, a pair of pistols, a long Kunjur, and a sword, besides a variety of powder flasks, etc., which altogether, made him weigh thirty stone.... The poor creature was now and then wont to sing some of his patriotic songs, which are of a peculiarly doleful and melancholy harmony."

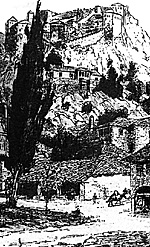

At right, a 19th Century sketch of Stolac in Hercegovina showing Ali Pasha Rizvanbegovic's fortress. Similar fortresses dominated the landscape throughout Bosnia and were the bases for the 38 great Kapetans who ruled the province in all but name during the Napoleonic Era.

At right, a 19th Century sketch of Stolac in Hercegovina showing Ali Pasha Rizvanbegovic's fortress. Similar fortresses dominated the landscape throughout Bosnia and were the bases for the 38 great Kapetans who ruled the province in all but name during the Napoleonic Era.

History

Like the rest of the Mediterranean region, Bosnia was part of the Roman Empire during the first centuries of the Christian era. After the fall of Rome, the area of Bosnia was contested between Byzantium and Rome's successors in the West.

However, in the late 6th and early 7th centuries, Bosnia was invaded and settled by Slavs, who formed a number of kingdoms and duchies. In the second quarter of the 7th century invading groups of Serbs and Croats moved into the area and asserted their control over the Slavs. Most scholars believe these new invaders were originally from Persia since both their tribal names and preserved historical names are of Persian origin. In time both of these later groups were slavicized by the more numerous Slavs. Throughout the Middle Ages the region continued to pass through a myriad of rapidly changing hands, finally ending up under at least nominal Hungarian control after 1180.

It was during this period that the region began to be known as Bosnia, from the Bosna River, which has it source just outside Sarajevo and flows north into the Sava. During the Middle Ages the Ieaders of this small region grew increasingly powerful until in time they ruled all of Bosnia and the name eventually came to be applied to the entire region.

Bosnia Independence

Around 1200, Bosnia fought for and gained its independence. To retain it, the Bosnians had to fend off not only the Hungarians, but also their powerful neighbor to the east, the Kingdom of Serbia The independent medieval Kingdom of Bosnia endured for more than 260 years (somewhat longer than the United States has thus far).

At that time its population was entirely Christian, but in a tolerant environment unusual for the Middle Ages there was not one Christian church but three. While most Bosnians were Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodoxy and a schismatic local Bosnian Church also had adherents. All three churches were organizationally weak, their clergy largely uneducated, and none could count on steady and exclusive state patronage. These factors would all later contribute to the decision by a large part of the Bosnian people to abandon Chrisdanity for Islam.

In the 14th century, the Ottomans embarked upon their conquest of the Balkans. By 1389 Serbia had suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of the Ottomans (at the famous battle of Kosovo) and had been reduced to the status of an Ottoman vassal. Through skillful maneuvering between its more powerful neighbors, Bosnia managed to retain its independence until 1463, when it also succumbed to the Ottomans.

The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia was greatly aided by the Bogomils, the heretical Christian sect which had been persecuted for centuries by both the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. The Bogomils accepted Islam and swiched their allegiance to the Ottomans.

The vast majority of Muslims in the western Balkans derive from this act. The wholesale conversion of nobility and peasants alike allowed the continuation of the old social and economic hierarchy more or less intact. Those who had been chieftains and members of the landed nobility before the conquest continued as such thereafter.

Herzegovina

It was also during this period that Herzegovina came into being. In 1448, during a time of turbulent fighting between the Hungarians, the Venetians and the Ottomans, with the kingdom of Bosnia in the middle, Stephen Vukcic adopted the title of Duke (Herceg) of Saint-Sava and forced Bosnia to recognize it. From that time on, the lands of his dukedom were known as Herzegovina. While Herzegovina held out longer than most of Bosnia, it too fell to the Ottomans in 1528.

The entire region was soon thereafter organized as the Vilayet (province) of Bosnia by the Ottomans. It was at that time a huge province, covering the whole territory of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, parts of Slavonija, Banja Luka and Krbava, and large parts of Dalmatia, as well as parts of present day western and southwestern Serbia and western and northern Montenegro.

Following the conquest of Bosnia, the victorious Ottoman armies marched on towards Vienna, and in the century that followed, many more Bosnians (for both spiritual and social reasons) dropped their allegiance to the weak and disorganized Chrisdan churches and adopted the triumphant faith of their Islamic conquerors.

The spread of Islam was aided by Dervishes, itinerant Muslim popular preachers, who taught a fairly broadminded and inclusive form of Islam that allowed the Bosnians to adapt their old tradidons to the new faith. So fanatical and devoted were these new converts that between 1544 and 1611 nine Grand Vezirs of the Ottoman Empire were from Bosnia.

As the years passed the Ottoman Sultans and their local governors embellished Bosnia's towns and cities with splendid mosques and established pious endowments that supported schools, Islamic seminaries, libraries, orphanages, soup-kitchens and alms houses. As a result, within Bosnia a distinctive Bosnian Muslim culture took form, with its own architecture, literature, social customs and folklore. Many Muslim Bosnians rose to join the ranks of the Ottoman ruling elite as soldiers, statesmen, Islamic jurists and scholars.

Those Bosnians who didn't accept Islam found the Ottomans to be tolerant of their non-Muslim minorities, allowing them full freedom to worship, live and trade as they pleased. At the same time, non-Muslims were subject to higher tax-rates and most civil and military offices of the Empire were reserved for Muslims.

For the next several hundred years Bosnia retained a distinct identity as the Vilayet of Bosnia, a key province of the Islamic Ottoman Empire. A native aristocracy of Bosnian Muslim notables ruled the province in all but name, ready to defend their autonomy by force of arms, if need be, against any efforts to curtail it.

Days of Prosperity and Glory

Thus Bosnia shared both in the Empire's days of prosperity and glory and the decline that eventually ensued. In the wars that the Ottomans fought against the Habsburgs and the Venetians at the end of the 17th century and during the 18th century, the borders of present day Bosnia and Herzegovina were gradually formed.

In 1699, in the Karlovci Peace Treaty, signed after sixteen years of the so called "Viennese" war, the Ottomans lost almost all their territories in Slavonija, Lika, Banija and Dalmatia Thus, the north western and southwestern borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina were defined as they are today, with only some slight differences.

As the Ottoman Empire's borders began to recede, Muslim Slavs who had been driven out of the lost prove inces found a refuge in Bosnia, reinforcing the already large Muslim element within its multi-ethnic population. These new arrivals were bitter against the Christian states which had driven them from their homes. They helped turned Bosnia into one of the most fundamentalist and reactionary provinces in the empire.

Throughout all the fighting of the Napoleonic Era, Bosnia's borders remained intact, a fact confirmed by the "Final Act" of the Congress of Vienna in June 1815. This agreement, signed by Austria, England, Prussia and Russia, acknowledged the Sultan as the legitimate ruler and master of the Ottoman Balkan territories.

But the Napoleonic Wars did have one important effect on Bosnia. The poor performance of the Janissaries during the conflict convinced Sultan Mahmud II to eliminate this turbulent force. He spent the next 10 years preparing to do away with the Janissaries who had done away with so many Sultan's before him, including his cousin, Sultan Selim III.

Janissaries in Bosnia

When the Janissaries were eliminated in Istanbul in 1826 during the "Blessed Affair," the Janissaries in Bosnia, among the most reactionary in the empire, refused to accept the ruling and rose in rebellion.

As part of the ruling local elite, they gained considerable sympathy for their cause and the Bosnians now began a period of active opposition to the central state. As a result, new Vezirs were sent in with large armed forces to enforce the Sultan's authority. Armed revolt broke out soon thereafter. Though some individual Janissaries survived, the corps was eliminated as an organized body by the end of 1827.

While successful, the campaign against the Janissaries further alienated the already strained relationship between Bosnia and the central state. When in 1830 the order was put out for recruits for the Sultan's new army, the powerful local warlord, Husein Kapetan, rebelled and launched a huge uprising. The Ottomans spent three years suppressing this revolt.

In fact, it was put down in the end only after Ali Pasha Rizvanbegovic, the powerful Kapetan of Stolac, threw his support behind the Ottoman governor. His price was the separation of Hercegovina from Bosnia as a Vilayet in its own right with himself as the hereditary Vezir.

Since most of the Kapetans had supported Husein's revolt, the Sultan in 1835 sent a new Vezir to Bosnia with orders to abolish the Kapetanijes and to set up new centrally-controlled administrative districts for the prove ince. This order set off another round of warfare which the state won. As a result, in 1837 the Kapetans and their districts were abolished. Those Kapetans who survived were exiled to Anatolia.

Bosnia remained a troubled province with further unsuccessful revolts in the 1840s and 1850s.

Bosnia's Ottoman centuries came to an abrupt end in 1878, when the Great Powers of Europe met in Berlin to decide what to do about the Ottoman Empire. Eyed hungrily by these same powers (as an object of colonial conquest), the Ottoman Empire by this time seemed ripe for the fall. Unable to pay its financial obligations, it was threatened both by internal civil disorder and by the aggressive designs of its neighbors.

What saved the Ottoman Empire from disintegration for another 40 years (until the end of World War I) was the inability of the Great Powers to agree on a division of the spoils. A compromise was reached at Berlin, according to which Ottoman finances were entrusted to an international conunission composed of the creditors, while the Empire's borders were, for the moment, to be left largely intact. There were to be some exceptions: Bosnia- Herzegovina was to be administered by AustriaHungary (which had felt left out in the race for colonies); the island of Cyprus was assigned to Britain (which insisted it needed it to protect the Suez Canal); and Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria were given full independence at Russia's insistence.

Sarajevo

Sarajevo was the chief city of Bosnia and one of the major cities of Ottoman Europe. At the time of the Ottoman conquest in 1451 the town of Vrhbosna was a village with a minor fortress which became the seat of the new governor of Bosnia. The governor's quarters were known as the Saraj and it was not long before the entire town was known as Sarajevo. Under the Ottomans it grew into a major city, ranking with Thessalonika and Edirne in size and importance, eclipsed only by Istanbul itself. It had an elaborate guild organization and the Ieaders of the guilds controlled many of the functions usually monopolized by the landed elite. While in time the governor's seat was moved north to Travnik, Sarajevo remained the region's chief town and a major administrative center for the region. The Muslim Bosnian Beys were so strong, though, that they refused to allow the Ottoman governors to live in the city, instead requiring them to administer the province from the town of Travnik. The city was built at a height of 1,500 feet at the confluence of the Migliazza (Miljacka) and Bosna rivers. Sarajevo was the seat of one of the 10 'lesser' Mollas of the 27 great Mollas of the Ulema. (also known as Serajevo, Sarjevo, Bosna-Saray, Bosna Sarayi, Bosna-Sarai, Saray-i Bosna)

Back to Dragoman Vol. 2 No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Dragoman List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by William E. Johnson

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com