As one of the largest empires in the world, and with travel being so slow, it was only natural that the Ottoman Empire would grant great power and discretion to its provincial governors.

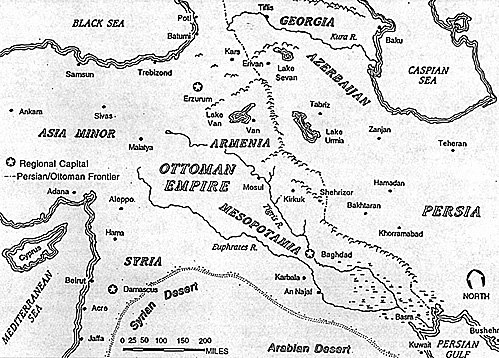

The most powerful of these were the governors of Rumelia, who had overall command of Ottoman forces in Europe; the governor of Kutahya, who commanded the hosts of Asia Minor; the governor of Damascus, who had responsiblity for the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina and command of the great annual pilgramage caravan, and the governor of Erzurum, who commanded in the east along the critical and always volatile frontier with Russia and Persia.

The governor of Erzurum was considered the senior governor of the Armenian region and in times of war he was responsible for mustering and leading the local provincial forces. Being located on the volatile frontier between Russia and Persia, and surrounded by the always tumultuous Kurds, the need for military preparedness was always high.

As eastern commander, the governor of Erzurum had the right to call upon the Pashas of of the neighboring districts of Kars, Akhalsikhe, Bayazid, Van, Mus, Mosul and Trebizond to supply him with troops. His duties also included investing the hereditary Pashas of Van, Mus and Bayazib with their insignias of office.

The province was organized in the normal Ottoman way, that is it was divided into Sanjaks which were further broken down into military estates (Timars). This meant the governor had a large force of feudal Sipahis to call upon in addition to his own provincial forces.

Sipahis

While the Sipahis in Europe had long abandoned the use of heavy armor, this was not the case for the Sipahis in the east. Here the Russians, with their muskets and cannons, were the new kids on the block. The main enemies were still the light horsemen of the Kurds and Persians, and the heavily armored "knights" of Caucasia and the various kingdoms and khanates of Georgia.

As a result, the eastern Ottoman Sipahis still often carried shields, dressed in suits of heavy mail and rode barded horses. They were usually armed with lance and sword and carried two to four pistols as well as a musket.

The governor's regular forces, though, were rather modest and probably consisted of not more than several thousand Janissaries and a similar number of light cavalrymen. Attached to this force was a European-style artillery corps led by Russian deserters from the fighting in Georgia.

The military might of the region when fully mobilized, though, could be very substantial. For example, in 1804 when Tayyar Mehmed Pasha, then governor of Erzurum, rose in rebellion against the Sultan he raised an army of more than 100,000 Kurds and hardy mountain bandits. It took the combined forces of former Grand Vezir Yusuf Ziya Pasha and local strong man Chapanoglu Suleyman Bey to drive back Tayyar's army, eventually forcing him to flee to Russia.

The Chapanoglu clan were strong supporters of Sultan Selim III's Nizam-i Jedid movement and raised several units of Nizam-i Jedid troops. Even after the Janissary revolts of 1807-1808 forced the Imperial government to abandon the Nizam-i Jedid, the Chapanoglus continued to raise, train and equip local units in the European style.

Erzurum

The city of Erzurum, the capital and most important city in the province of Erzurum, was located near the source of the Euphrates and Aras Rivers on a high, fertile plain, 450 miles east of Ankara and 110 miles southeast of Trebizond. The heavily-farmed plain was described by one European visitor as "the site of the terrestrial paradise." A major agricultural trading center, it was the most important strategic fortress of Armenia against both the Russians and the Persians. It was famous for its metal working industry.

A description of the city was provided by James Morier, an agent in the British diplomatic service who visited the city on June 15, 1809. In his book, A Journal Through Persia, Armenia, and Asia Minor to Constantinople in the Years 1808 and 1809, London, 1812, he wrote:

"The city presents itself in a very picturesque manner; its old minarets and decayed turrets, rising abruptly to the view. Erzurum is built on a rising ground; on the highest part is the castle, surrounded by a double wall of stone, which is checkered at the top by embrasures, and strengthened here and there by projections in the fashion of bastions, with opening fit for the reception of cannon. ... It has four gates, which are covered with plates of iron. ... The whole is well built. The houses are in general built of stone, with rafters of wood and terraced. Grass grows on their tops and sheep and calves feed there. The shops of the bazaar are well stocked, and the place exhibits an appearance of much industry. The streets are mostly paved. There are 16 baths and 100 mosques; several of the latter are creditable buildings, the domes of which are covered with lead, and ornamented with gilt balls and crescents. ... To the east of the town is an old tower of brick, the highest building in Erzurum, which is used as a look-out-house, and serves as the tower of the Janissaries There is a clock at the summit, which strikes the hours. ... In the city are four to five thousand families of Armenians, and about 100 of Greek. The former have two churches, the latter one. There are perhaps 1,000 Persians who live in the Carvanserai and manage the trade of their own country. Trebizond is the port on the Black Sea to which the commerce is conveyed."

During his visit, Morier estimated the Turkish inhabitants at about 250,000. Morier said that the name of the province was derived from the words Arza of Rum, (that part of Asia Minor occupied by the Roman Empire), which over the years had become Erzurum.

Morier described the land around the city as richly cultivated and studded with villages, but almost destitute of timber. Much of the population in the area was Armenian. Troops from the region saw a great deal of action during the Napoleonic Period. When the French Revolution broke out the Ottomans were at war with both the Russians and the Austrians. The local forces were heavily engaged against the Russians in Georgia and supplied the bulk of the forces that fought the Russians in and around Anapa on the north shore of the Black Sea in 1790-91.

In the summer of 1800, Tayyar Pasha led a 7,000-man force from Erzurum for service against the French. Between 1802 and 1805 much of the region was convulsed in civil war. Order was not restored until the out-break of a new war with Russia in 1806, which helped focus the local warlords on an external enemy.

In the summer of 1807, a Russian force, striking south from Georgia, defeated a hastily prepared force of 30,000 men under Yusuf Ziya Pasha on the east side of the Black Sea near Kars on the banks of the Arpa Su River.

Fighting continued in the region until 1812, with the Russians slowly gaining ground year after year, but unable to decisively defeat the Ottomans. In the treaty of 1812 the Russians were forced to surrender almost all their conquests on the eastern side of the Black Sea.

Map

Back to Dragoman Vol. 2 No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Dragoman List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by William E. Johnson

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com