While Napoleon did not invent propaganda, he helped refine it into an art

form. This was well known to his troops who would use the phrase "to lie like a

dispatch" to describe any particularly outrageous statement.

While Napoleon did not invent propaganda, he helped refine it into an art

form. This was well known to his troops who would use the phrase "to lie like a

dispatch" to describe any particularly outrageous statement.

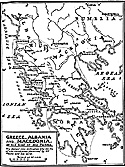

Large Map (slow download: 116K)

Jumbo Map (slow download: 416K)

When the French came into possession of the Ionian Islands as a result of the Treaty of Campo-Formio in 1797, among the first French citizens to arrive were Napoleon's propaganda teams. In time they were to achieve significant success with not only the Greek citizens of the Ionian Islands, but with many of the mainland Greeks as well.

Among the more successful of these propagandists were the brothers Stefanopoli. They were members of the Greek colony at Cargese in Corsica, and as cover, were sent on one of those semiscientific, semi-political missions dear to foreign offlces. They succeeded admirably in spreading Napoleon's fame in the Peloponnese.

It was not long before a legend began to grow up around the victorious general. Greek philologists discovered that his name was merely an Italian translation of two Greek words and that he must therefore be descended from the Imperial family of the Kalomeroi Porphyrogennetoi, whose glories he was destined to renew.

Greek historians, remembering the emigration of the Mainates to Corsica more than a century earlier, boldly proclaimed him the offspring of one of those Spartan families. The story became so accepted among the Greeks that the women of Maina kept a lamp lighted before his portrait, "as before that of the Virgin Mary."

The idea of a restoration of the Byzantine empire with his aid became general among the Greeks, and Bonaparte was widely regarded as the deliverer of the Hellenic race.

The fear of such an occurrence seemed very real to the Ottomans. Hasan Pasa, the Vali (governor) of the Morea, began to send increasingly worried reports to the Porte telling tales of liberty and equality on the borders of the empire. His reports told of speeches and ceremonies recalling the ancient glories and liberties of Hellas and promises of their restoration, of French contacts with rebels and dissidents in Ottoman Greece and of French plans to annex the Morea and Crete.

As a result of continued secret French contacts with the Greeks and several dissident Pashas, notably Ali Pasha of Janina, in 1798 Sultan Selim III became convinced that the mysterious French force assembling in Toulon was intended to attack his empire. He expected the blow to fall on the Morea or perhaps Crete or Cyprus.

He was so convinced of this that he ordered all French technicians and military advisers, key elements in his plan to modernize the Ottoman army, to leave the empire, and required all French citizens to register with local authorities.

Sultan Selim's guess about a French invasion proved correct. But instead of Greece, the French attack fell on Egypt, forcing the Ottomans to ally with their bitterest enemies, the Russians, against their oldest friends, the French.

While the French expedition to Egypt ended in disaster, after its conclusion Napoleon used all his diplomatic skills to soon return to the good graces of the Sultan. Even so, Napoleon continued to spend a significant effort to maintain the myth that he was the friend of the Greek people, going as far as to actually supply weapons and ammunition to Greek rebels in the early 1800s.

He also established consulates in the capitals of Wallachia and Moldavia, provinces ruled by members of the Greek Phanariotes. Napoleon wanted to make sure that the "Greek option" always remained openÄa secret trump card, ready to play in the event he needed it.

Cooling Passions

In 1804 the British sent John Philip Morier, who had been born in the Greek dominated city of Smyrna, to the Morea to try to cool the pro- French passions of the Greeks. While he did what he could, he reported that if the French should invade, the Greeks would rise to a man to support them. "The Greek character resembles the French. They are both equally false, vain and ambitious of power, which they ever abuse," he reported back to his superiors.

In the ebb and flow of events it came to pass that the time never came for Napoleon to play the Greek card. First it had value when the French took the Ionian Islands. Then it lost value as the Ionian Islands fell into the hands of the Russians. Then it gained value again as the French took over first the Dalmatian shore and then the Ionian Islands again.

But then the British arrived and took the islands away once and for all. Then it seemed like the prefect time had come to use the Greek card when, as part of their negotiations atTilsit, Napoleon and Czar Alexander developed their secret plan to divide up the Ottoman Empire. But before this plan could be put into effect, the two Emperors began to squabble over the fate of Istanbul. This squabbling eventually led to the French invasion of Russia in 1812, which in turn led to the ultimate defeat of Napoleon in 1815.

All one can do is try to imagine what might have been had events turned out a little differently and Napoleon had tried to become King of the Greeks.

Back to Dragoman Vol.1 No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Dragoman List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by William E. Johnson

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com