Adolf Hitler regarded the winter defensive battles to be his own personal triumph, won against heavy military odds and in spite of the advice of the German Army's senior officers. In rhetorical terms that made it seem as if he had personally braved Russian bullets (Hitler in fact had not visited front commanders since late November), the Fuhrer gave his

own assessment of the campaign to Dr. Joseph Goebbels on 20 March 1942. As the propaganda minister wrote in his diary:

Adolf Hitler regarded the winter defensive battles to be his own personal triumph, won against heavy military odds and in spite of the advice of the German Army's senior officers. In rhetorical terms that made it seem as if he had personally braved Russian bullets (Hitler in fact had not visited front commanders since late November), the Fuhrer gave his

own assessment of the campaign to Dr. Joseph Goebbels on 20 March 1942. As the propaganda minister wrote in his diary:

A lone German sentry stands guard over snowed-in vehicles, February 1942

Sometimes, the Fuhrer said, he feared it simply would not be possible to survive. Invariably, however, he fought off the assaults of the enemy with his last ounce of will and thus always succeeded in coming out on top. Thank God the German people learned about only a fraction of this.... The Fuhrer described to me how close we were during the past months to a Napoleonic winter. Had he weakened for only one moment, the front would have caved in and a catastrophe ensued that would have put the Napoleonic disaster far into the shade.

[129]

Hyperbole aside, the winter fighting had borne Hitler's peculiar stamp, first in the refusal to allow withdrawals and then, after 15 January, in his insistence that Army Group Center's retreat be conducted in small costly steps. Moreover, the Fuhrer's leadership style was already corroding the bonds of trust and confidence between various field commanders. As a precaution against the dictator's wrath, some officers kept written copies

of their orders to subordinates as proof that Hitler's instructions had been passed on unaltered. (Field Marshal von Kluge, since December the commander of Army Group Center, was a master practitioner of this artifice.) Recriminations were another symptom of this disease.

On 30 April 1942, for example, Kluge demanded an official inquiry to ascertain why the 98th Division (whose combat strength was less than 900 men) had failed to carry out impossible orders to crush a fortified Soviet bridgehead at Pavlovo held by superior enemy forces. That 12 officers and 450 men had fallen in the German counterattack mattered little to Kluge, who needed scapegoats.

[130]

The Russian winter battles left their imprint on the Fuhrer as well. The success (if the avoidance of total disaster could be described as such) of the stand-fast strategy reinforced Hitler's conviction that his own military instincts were superior to the collective wisdom of the front commanders and the General Staff. It also convinced him that will and determination could triumph over a materially stronger enemy. Armed with these delusive notions, Hitler ordered German troops to stand fast on many future battlefields, though more often with disastrous than with victorious results. The seeds of future stand-fast defeats at Stalingrad and El Alamein, as well as in Tunisia, the Ukraine, and Normandy, were planted in Hitler's mind during the 1941-42 winter struggle.

On a less grand level, the German Army set about drawing its own conclusions about the winter fighting. Responsibility for these assessments was divided. The Operations Branch of the Army General Staff was responsible for seeing that major lessons learned were immediately reported and disseminated to interested field commands. The General Staff's Training Branch had responsibility for the more deliberate adjustment of doctrine

through the publication of new field manuals and training directives. Finally, field commanders from army group level downward all had some latitude and authority in modifying the tactical practices of their own forces.

After-action reports from frontline units constituted the primary information base on which these agencies depended. When necessary to amplify this information, General Staff officers visited forward units or interviewed officers returning to Berlin from frontline duty. (Even General Halder, the chief of the Army General Staff, frequently conducted such firsthand consultations. [131])

Fourth Panzer Army ordered the most thorough early assessment of the winter fighting. On 17 April 1942, it sent a memorandum to its subordinate units ordering them to prepare comments on general winter warfare experiences. As guidance, this memorandum posed more than forty specific questions about tactics, weapons, equipment, and support activities. Thirteen of these questions dealt directly with defensive doctrine and included such matters as the choice of a linear defense versus a strongpoint system, the siting of strongpoints, the construction of obstacles, patrolling, and the composition and role of reserves.

[132]

While the resulting reports provided valuable technical information in all areas,

comments on antitank defense and on strongpoint warfare in general caused the greatest

doctrinal stir.

The German Elastic Defense had been designed primarily for positional defense

against infantry, and opposing tanks had previously been regarded simply as supporting weapons for the enemy's foot troops. The Barbarossa campaign and winter fighting had exposed the woeful inadequacy of German antitank guns against Russian armor; therefore, Soviet tank attacks--with or without infantry support--had emerged as a major threat in their own right.

In its response to the Fourth Panzer Army memorandum, the German XX Corps noted that, due to the weakness of German antitank firepower, otherwise weak enemy attacks posed a severe danger to German defenses if the attacking force was supported by even one heavy tank.

[133]

Overall, the reports that were returned to Fourth Panzer Army emphasized this fact

and gave careful considerations to the defensive measures necessary to defeat Soviet tanks.

German prewar antitank doctrine had focused on separating enemy tanks and infantry. Since June, battles against Russian armor had confirmed the theoretical effectiveness of this technique. Under attack by Red Army tankinfantry forces, German

units frequently succeeded in driving off or pinning down the Soviet infantry with artillery,

small-arms, and automatic weapons fire. This tactic was abetted by the generally poor Soviet combined arms cooperation, as Stalin admitted in his 10 January directive. In fact, several German commanders noted how easily Russian tanks and infantry could be separated and the surprising tendency of the enemy occasionally to discontinue otherwise successful tank attacks when the accompanying infantry was stripped away.

[134]

Confirming the general thrust of German antitank doctrine, the 35th Division's report declared that "the most important measure [was] to separate the tanks from the infantry."

[135]

What troubled German commanders was not the splitting of enemy armor and

infantry but the practical difficulties in destroying Soviet tanks. German prewar thinking, reflecting the wisdom passed down from the Great War, had regarded tanks without infantry support to be pitiable mechanical beasts whose destruction was a relatively simple drill. Given the ineffectiveness of German antitank guns, such was clearly not the case on the Russian Front.

Most German antitank guns needed to engage the well-armored Russian tanks at extremely close range in order to have any chance at all of destroying or disabling them. To accomplish this, the antitank guns were placed in a defilade or reverse-slope position behind the forward infantry. Hidden from direct view, the Paks then had a good chance for flank

shots at enemy tanks rolling through the German defenses. The disadvantage of this system, of course, was that the Paks could not engage Soviet armor until it had actually entered the German defensive area.

[136]

The only German weapon able to kill Soviet tanks at extended ranges was the 88-mm flak gun. However, this weapon was so valuable and, due to its high silhouette, so vulnerable that it, too, was commonly posted well behind forward German positions. Thus hidden, the heavy flak guns were safe from suppression by Russian artillery and from early destruction by direct fire; they could not, however, use their extended range to blast enemy

tanks far forward of the German lines.

[137]

Thus, neither the lighter Paks nor the heavy 88-mm flak guns provided an

effective standoff antitank capability. The lack of powerful antitank gunfire placed enormous pressure on German infantrymen in two ways. First, it was not uncommon for German infantry positions to be overrun by Soviet tanks. Assaulting in force, Russian armored units were virtually assured

of being able to rush many of their tanks through the German short-range antitank fire, over the top of German fighting positions, and into the depths of the German defenses. This shock effect wracked the nerves of German soldiers, who found little comfort in an antitank concept that, in practice, regularly exposed them to the terror and danger of being

driven from their positions by Soviet T-34s. Echoing sentiments first voiced by German commanders twenty-five years earlier, one officer warned, "The fear of tanks (Panzerangst) must disappear. It is a question of nerves to remain [in fighting positions being overrun]. "

[138]

Second, German infantrymen were routinely given the dangerous task of

destroying Russian tanks by close combat measures (mines, grenades, fire bombs). Though such methods had been discussed in prewar manuals and journals, the powerlessness of the

German antitank guns forfeited to the beleaguered infantry a far greater burden than anyone had foreseen. For an infantryman, attacking a Soviet tank was not easy. He had to crouch

undetected until the tank passed close to his hiding place and then spring forward to attach a magnetic mine to the tank's hull or to disable the tank's tracks or engine with a grenade. In doing so, the soldier exposed himself to machine-gun fire from other tanks (which,

naturally, were particularly alert for such attacks) and also risked being crushed by a suddenly swerving tank or even wounded by the explosion of his own antitank device.

To facilitate the close assault of enemy tanks and to cloak the movements of the German infantry, some German units released smoke on their own positions as the enemy tanks closed. However, this tactic was dangerous, as such smoke interfered with aimed German fire against any Russian infantry and also tended to enhance the shock value of the menacing armor.

[139]

Protesting the unbearable strain that infantry-versus-tank combat placed on German soldiers, the 7th Infantry Division stated bluntly in its report: "It is wrong to pin the success of antitank defense on the morale of the infantry." The 7th Division's report strongly advocated a

thickening of forward antitank weapons, including the forward placement of 88-mm flak guns "to smash [Soviet] tank assaults forward of the German defensive line [italics in original]."

[140]

German strongpoint tactics during the winter fighting increased the problems of antitank defense. Strongpoints were subject to attack from all directions, thereby complicating the siting of the relatively immobile German antitank guns. When attacking enemy armor, German infantrymen preferred the protection of continuous trenches, since these gave them a covered way to scuttle close to the tanks without undue risk of detection.

[141]

However, strongpoints -- particularly those confined to villages -- were difficult to

camouflage. Therefore, Russian tanks could circle outside the defensive perimeter, blasting

away at the German positions and probing for a weak spot, without fear of a surprise attack by hidden German infantry. In the same way, Soviet armored thrusts through the gaps between strongpoints also avoided the lurking German infantrymen. For this reason, many German commanders prepared connecting trenches between strongpoints solely to move infantry antitank teams into the path of bypassing Russian tanks.

After nearly one year of brutal combat in Russia, antitank defense thus loomed as a major vulnerability in German defensive operations. German antitank guns lacked penetrating power and were relatively immobile. Soviet tank assaults exposed German infantrymen to terrific strain, both from the general likelihood of being overrun and from the necessity to combat Russian tanks with primitive hand-held weapons. If anything, the experiences of winter combat had shown that these difficulties were even greater then than

during earlier battles. Fortunately for the Germans, the Soviets' tactical ineptitude and early tendency to disperse armor into small units spared the Germans even harsher trials.

Early combat reports, such as those ordered by Fourth Panzer Army, spurred adjustments to German antitank measures. Efforts to improve German antitank weaponry were greatly emphasized, resulting in the eventual introduction of heavier guns. The production of German self-propelled assault guns was also accelerated, partly in answer to the need for a more mobile antitank weapon. Moreover, new German tanks received

heavier, high-velocity main guns capable of duelling the Soviet T-34s, and older-model German tanks were refitted with heavier cannon as well.

[142]

Efforts to improve the German antitank capability went beyond technological remedies. Since it remained necessary in the short term to rely heavily on infantrymen (and, in some units, combat engineers) to destroy tanks in close combat, the German Army did

its best to prepare German soldiers for that task. Various instructional pamphlets were printed giving detailed information on the vulnerabilities of Russian tanks and the most effective methods for disabling them. For example, in February 1942, the Second Army rushed a "Pamphlet for Tank Destruction Troops" to its own units even before the winter

battles had subsided.

[143]

General Halder reviewed the reports of frontline units and conferred with the

German Army's Training Branch on the preparation of a new manual on antitank defense.

[144]

Also, the German leaders did not neglect the psychological dimension of antitank combat: beginning on 9 March 1942, soldiers who had single-handedly destroyed enemy tanks were authorized to wear a new Tank Destruction Badge, which helped improve morale.

[145]

German combat reports also generated a great deal of interest in the strongpoint defensive system. The assessments culled by Fourth Panzer Army contained sharp differences of opinion on this point. The 252d Infantry Division dismissed the strongpoint methods, arguing that "village strongpoints [had] not proven themselves effective in the defense. After short concentrated bombardment they [exacted] heavy losses. A continuous defensive line [was] in every case superior to the strongpoint-style deployment." The 252d Division rejected the supposed

strongpoint advantages, pointing out that "experiences with the strongpoint defense were muddy.... It did not prevent infiltration by enemy forces, especially at night. It [strongpoint defense] cost considerable blood and strength to destroy penetrating enemies by counterattack."

[146]

Other assessments were less harsh, conceding the value of strongpoints as an expedient measure. Though expressing a strong preference for a doctrinal linear defense in depth, the XX Corps grudgingly acknowledged the importance of strongpoints under certain conditions: "A continuous defense line is successful and strived for. A strongpoint-style defense may be necessary when insufficient forces are available for a continuous front. It is only tolerable for a limited time as an emergency expedient."

[147]

Although no unit suggested a general adoption of strongpoint defensive measures over the Elastic Defense system, the widespread use of strongpoints seemingly warranted closer study. General Halder therefore decided on a formal investigation into the strongpoint issue. On 6 August 1942, the chief of the General Staff ordered a survey of frontline units on the terse question, "Strongpoints, or continuous linear defense?"

[148]

The purpose of this study was not to reach a consensus; rather, it was to seek information of doctrinal value from as many different sources as reasonably possible. Fourth Army, for example, submitted responses that were prepared by every subordinate corps and division commander and by most regimental and many battalion commanders as well.

The monographs returned as a result of General Halder's inquiry provided a thorough critical assessment of German defensive tactics during the previous winter. In practice, all German units had compromised doctrinal Elastic Defense methods to some extent, and most divisions had at least experimented with strongpoint measures. In their reports, the surveyed commanders argued the relative merits of the strongpoint system and

tried to define precisely its advantages, disadvantages, and suitability for general defensive use.

Predictably, the most commonly cited advantages were the obvious ones of shelter and concentration of limited resources. However, several veteran officers also pointed out other less-obvious benefits of strongpoint warfare. Units disposed in strongpoints were more easily controlled than those arrayed in a linear defense, thus simplifying the leadership

problems of the few remaining officers and NCOs.

[149]

Within strongpoints, wrote the commander of the 289th Infantry Regiment, even poorly trained soldiers could be kept under tight rein by their junior leaders.

[150]

Similarly, the chief of staff of the Second Army considered strongpoints beneficial to discipline and training, a vital matter since "the training status of the troops and the quality of the infantry junior leaders had noticeably declined."

[151]

Strongpoints also bolstered the sagging morale and pugnacity of individual soldiers: troops spread out in a linear defense tended to perceive themselves as solitary fighters and often were less steadfast under fire than those fighting in the close company of strongpoint

garrisons. In this regard, the 331st Division expressed concern about its growing numbers of young and inexperienced replacements.

[152]

Against these advantages, German officers listed the serious problems that, in their experience, had attended the use of strongpoints. Individual

strongpoints invited isolation and destruction in detail by superior Soviet forces. Since separated strongpoints had been unable to secure the German front against enemy penetrations, strong Russian forces had frequently managed to shoulder their way between strongpoints and deep into the German rear. Also, smaller Soviet infiltration parties had wrought havoc throughout the German defensive area. Because of the lack of doctrinal guidance, the use of nonstandard strongpoint tactics by some divisions had unintentionally

exposed the flanks of neighboring formations deployed in a linear defense.

[153]

Although German officers also found fault with their own occasional use of linear defenses, the faults were generally attributed to insufficient resources (excessively wide sectors, lack of depth, unavailability of mobile reserves). However, the systematic criticisms of the strongpoint style of defense pointed out inherent, fundamental flaws in the strongpoint concept. Strongpoints, in the view of German commanders, would always be

subject to isolation, and Soviet forces would always be able to force passage between strongpoints, even if the Germans disposed of larger forces. These flaws cast into doubt Hitler's prediction that the mere control of villages and road junctions would arrest Soviet offensive momentum. As one divisional report delicately put it, this contention remained "unproven in practice."

[154]

Consequently, German officer sentiment ran strongly against a general reliance on strongpoint defenses. To most German field commanders, a strongpoint system remained an emergency expedient prompted by the exceptional conditions of the 1941-42 winter campaign. In their answers to Halder's query, many leaders quickly pointed out that, as combat conditions had allowed, their units had abandoned their exclusive reliance on

strongpoints in favor of more traditional methods. As one battalion commander explained: "Except as under the special conditions reigning during the 1941/42 winter campaign, one should reject the strongpoint system and strive for a continuous HKL [main line of resistance]. The strongpoint system can only be an emergency measure for a short time, and must form the framework for a continuous line as was the case during the winter."

[155]

Some unit commanders, though firm in their endorsement of an orthodox defense in depth, expressed their intent to incorporate some strongpoints into any future defensive system. With the passing of winter, German divisions on the Eastern Front began organizing their positions, aided by the arrival of fresh divisions and a trickle of replacements. As this

occurred, German lines increasingly resembled the Elastic Defense prescribed in Truppenfuhrung. Within this burgeoning defense in depth, strongpoints were occasionally retained as combat outposts or, more commonly, as redoubts within the depth of the main battle zone. In contrast to the winter strongpoints, however, these positions generally were

smaller and were knitted into the defensive system with connecting trenches. The XLIII Corps, summarizing the views of its subordinate divisions, saw nothing new in this: "The best style of defense is that laid down in Truppenfuhrung-many small, irregularly-located nests, deployed in depth, composing a defensive zone whose forward edge

constitutes the HKL [italics in original]."

[156]

In the overall context of German defensive doctrine, this addition of greater numbers of small strongpoints was relatively minor. (Small squad-size redoubts had been part of the original German Elastic Defense as early as 1917, and a few officers even cited passages from Truppenflihrung

allowing for such measures.

[157])

The stream of winter after-action reports prepared by German units did not result in any major new doctrinal publications. Therefore, Truppenfuhrung remained the German Army's basic doctrinal reference for defensive operations. In fact, after extensive study, the winter defensive crises were dismissed as products of extraordinary circumstances. The

exceptional conditions of the previous winter--which, the Germans hoped, would not be repeated in the future--invalidated any general doctrinal judgments that might otherwise have

been made.

Furthermore, any hasty revision of German defensive doctrine would have

seemed, in the summer of 1942, to be a superfluous and even a defeatist gesture. While General Halder and other members of the General Staff sifted through the grim after-action reports about the winter fighting, German armies were again on the march in Russia. On 5 April 1942, Hitler ordered preparations for a new German summer offensive to win the war in the east in one more blitzkrieg campaign.

A camouflaged German antitank gun defends a village strongpoint, winter 1941

A camouflaged German antitank gun defends a village strongpoint, winter 1941

A drawing of German infantrymen attacking Soviet T-34 tanks with grenade clusters

A drawing of German infantrymen attacking Soviet T-34 tanks with grenade clusters

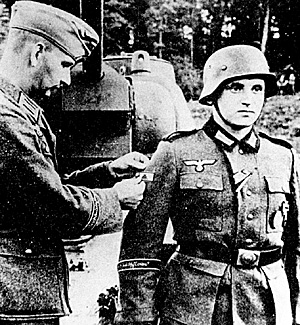

Soldier of Grossdeutschland Division receives the Tank Destruction Badge. Behind him, a T-34 tank.

Soldier of Grossdeutschland Division receives the Tank Destruction Badge. Behind him, a T-34 tank.

Back to Table of Contents -- Combat Studies Research # 4

Back to Combat Studies Research List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com