The Soviet winter counteroffensive unfolded in two distinct stages. The first stage, beginning on 6 December and lasting approximately one month, consisted of furious Russian attacks against Army Group Center. These blows were to drive the Germans back from the gates of Moscow and, in so doing, destroy the advanced German panzer groups if possible.

The Soviet winter counteroffensive unfolded in two distinct stages. The first stage, beginning on 6 December and lasting approximately one month, consisted of furious Russian attacks against Army Group Center. These blows were to drive the Germans back from the gates of Moscow and, in so doing, destroy the advanced German panzer groups if possible.

Dead Russian troops and destroyed Soviet tanks litter the snowy field in front of German defensive positions, winter 1941-42

These attacks breached the thin German lines at several points and sent Hitler's armies reeling westward until the stand-fast order braked their retreat. By the end of December, the front had temporarily stabilized, with most German units on the central sector driven to a form of strongpoint defense.

Encouraged by the success of these first attacks, Joseph Stalin ordered an even grander counteroffensive effort on 5 January 1942. This second stage mounted major Soviet efforts against all three German army groups and aimed at nothing less than the total annihilation of the Wehrmacht armies in Russia. Tearing open large gaps in the German front, Soviet armies advanced deep into the German rear and, in mid-January, created the most serious crisis yet. Grim reality finally succeeded where professional military advice had earlier failed, and Hitler at last authorized a large-scale withdrawal of the central German front on 15 January. Even with this concession, the German position in Russia remained in peril until Soviet attacks died out in late February.

To appreciate the tactical effectiveness of the German winter defensive methods, it is important to understand the nature of the Soviet counter offensives. German defensive actions did not take place in a tactical vacuum; rather, their value must be measured in relation to the peculiarities of Russian offensive methods during the 1941-42 winter.

Throughout the winter, the hardscrabble German defensive efforts benefited from the general awkwardness of Soviet offensive operations. The strongpoint defensive tactics adopted by German units exploited certain flaws in Russian organization, leadership, and combat methods. However, this exploitation was not purposeful, for as already discussed, other factors compelled the Germans to use strongpoints. Also, many of the particular

Soviet internal handicaps were unknown to the Germans. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the German strongpoint measures was enhanced by peculiar Red Army weaknesses.

Throughout the winter, the hardscrabble German defensive efforts benefited from the general awkwardness of Soviet offensive operations. The strongpoint defensive tactics adopted by German units exploited certain flaws in Russian organization, leadership, and combat methods. However, this exploitation was not purposeful, for as already discussed, other factors compelled the Germans to use strongpoints. Also, many of the particular

Soviet internal handicaps were unknown to the Germans. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the German strongpoint measures was enhanced by peculiar Red Army weaknesses.

Though achieving great success in their winter counteroffensives, the Soviet armies possessed overwhelming strength only in relation to their enfeebled German opponents. The Barbarossa campaign had inflicted frightful losses on the Red Army, and the Russian forces that assembled for the December attacks were a mixture of fresh Siberian divisions, burned-out veteran units, and hastily raised militia. At almost every level, these Russian forces were troubled by inadequate means and inferior leadership.

The first Soviet attacks against Army Group Center were executed by the Western Front, now under the command of the ubiquitous General Zhukov. Planning for the assault had begun only at the end of November, and preparations were far from complete when the counteroffensive began. Though nine new Russian armies were concentrated around Moscow, the assaulting forces also included many divisions ordered straight into the attack

after weeks of fierce defensive fighting. Except for some Siberian units, the newly deployed formations were generally understrength, poorly trained, and lacking in equipment. The rebuilt Soviet Tenth Army, for example, had no tanks or heavy artillery and was short infantry weapons, communications gear, engineering equipment, and transport. Although the Tenth Army nominally fielded ten rifle divisions, its overall strength, including

headquarters and support troops, scarcely amounted to 80,000 men. Ammunition shortages also afflicted Zhukov's command, with many units having only enough stocks to supply their leading assault elements. Large mobile formations were virtually nonexistent; for example, Western Front forces included only three tank divisions, two of which had almost

no tanks. Most of the available tanks were instead scattered among fifteen small tank brigades, each having a full establishment strength of only forty-six machines.

[102]

These problems were compounded by amateurish leadership and faulty doctrine. Instead of concentrating forces on narrow breakthrough sectors, inexperienced Soviet commanders and staffs assigned wide attack frontages (nine to fourteen kilometers) to each rifle division by the simple method of "distributing forces and equipment evenly across the entire front."

[103]

Marshal S. I. Bogdanov, recalling his experiences in the Moscow counteroffensive, noted a similar deficiency in using the few Soviet tank forces, namely, "the tendency to distribute tanks equally between rifle units ... which eliminated the possibility of their

massing on main routes of advance." Furthermore, the Soviet tanks were cast solely in an infantry support role. "All tanks," continued Bogdanov, "which were at the disposal of the command, were assigned to rifle forces and operated directly with them...or in tactical close coordination with them..." [104]

These errors further diluted the Soviet combat power and weakened the Russian

capacity to strike swiftly into the enemy rear with sizable mobile forces.

Nevertheless, Zhukov's Western Front armies possessed more than enough brute

strength to overwhelm the weak German lines opposite Moscow. They did so with a

notable lack of finesse, however, often butting straight ahead against the flimsy German

positions when ample opportunity existed to infiltrate and outflank the invaders. As one

Soviet analyst criticized, "Although the [German] enemy was constructing his defense on

centers of resistance and to slight depth (3-5 km), and there were good opportunities for

moving around his strongpoints, our units most frequently conducted frontal assaults against

the enemy."

[105]

When breakthroughs were achieved, follow-up thrusts minced timidly forward as

Soviet commanders looked fearfully to their flanks for nonexistent German ripostes.

[106]

Oafish Red Army attempts to encircle German formations closed more often than

not on thin air.

Impatient at these mistakes, General Zhukov issued a curt directive to Western

Front commanders on 9 December, decrying the profligate frontal attacks as "negative

operational measures which play into the enemy's hands." Zhukov ordered his subordinates to avoid further "frontal attacks against reinforced centers of resistance" and urged instead that German strongpoints be bypassed completely. The bypassed German strongpoints would hopefully be isolated by the Soviet advance and then later reduced by following echelons. To lend speed and depth to his spearheads, Zhukov also ordered the formation of special pursuit detachments composed of tanks, cavalry, and ski troops.

[107]

Although these measures increased the pace of the Russian drive, they failed to

increase appreciably the bag of trapped German units and even may have helped to save

some retreating German forces from destruction. As previously discussed, German units

turned to strongpoint defensive methods during this chaotic retreat period. These

strongpoints massed the slender German resources in a way that the diffuse Soviet

deployment did not, thereby reducing the relative German tactical vulnerability. Zhukov's

Front Directive of 9 December prohibited Russian divisions from breaking down these

centers of resistance by direct assault, even though the Red Army forces could certainly

have achieved this in many instances. In accordance with Zhukov's instructions, the

Russian forces tried instead to snare the retreating Germans by deep maneuver. At this

stage of the war, however, the Red Army possessed neither the skill, experience, nor

(except for the few pursuit groups) mobility to accomplish these operations crisply and

effectively. Time and again, German divisions dodged would-be envelopments or, when

apparently trapped, carved their way out of clumsy encirclements.

[108]

Even Zhukov's sleek pursuit groups failed to cut off German forces. These mobile

detachments-often acting with Soviet airborne forces-caused alarm in the German rear

areas, but the Russian cavalry and ski troops were generally too lightly armed to do more

than ambush or harass German combat formations.

The first stage of the Soviet winter counteroffensive drove the Germans back from

Moscow but failed to destroy the advanced German panzer forces. The divisions of Army

Group Center, slipping into a strongpoint style of defense as they retreated, by luck adopted

a tactical form that the advancing Russians were not immediately geared to smother. Even

though many German divisions were mauled at the outset of the Red Army

counteroffensive, other German units probably owed their subsequent survival to the

purposeful Soviet avoidance of bludgeoning frontal attacks and to the maladroitness of

Soviet maneuver.

When Hitler ordered the German armies to stand fast on 16 December, the

opening Soviet drives had already spent much of their offensive energy. The initial Russian

attacks had been planned, as Zhukov later explained, merely as local measures to gain

maneuver space in front of Moscow.

[109]

The near-total dissolution of Army Group Center's front exceeded the most

optimistic projections of the Soviet High Command. Having planned for a more shallow, set-piece type of battle, the Russians were unable to sustain their far-ranging attacks with supplies, replacements, and fresh units. On the contrary, Russian offensive strength waned drastically as Red Army divisions moved away from their supply bases around Moscow. Consequently, Hitler's dogmatic no-retreat directives, issued at a time when some Soviet

units were already operating 50 to 100 miles from their starting lines, stood a much greater chance of at least temporary success than would have otherwise been the case.

During the latter part of December, both sides struggled to reinforce their battered forces. Hitler ordered the immediate dispatch of thirteen fresh divisions to the Eastern Front from other parts of German-occupied Europe.

[110]

The arrival of these units proceeded slowly, retarded by the same transportation difficulties that dogged the German supply network in Russia. To speed the transfer of badly needed infantrymen, Luftwaffe transports airlifted several infantry battalions straight from East Prussia to the battle zone--in retrospect, a measure of questionable merit since the

reinforcements arrived without winter clothing or heavy weapons.

[111]

The frantic German haste to introduce these new units into the fighting led to bizarre incidents. In one case, the detraining advance party of a fresh division was thrown straight into battle even though many of the troops involved were only musicians from the division band."

[112]

In still another case, elements of two separate divisions were combined into an ad hoc battle group as they stood on railroad sidings and then hurried into the fray without further

regard to unit integrity or command structure.

[113]

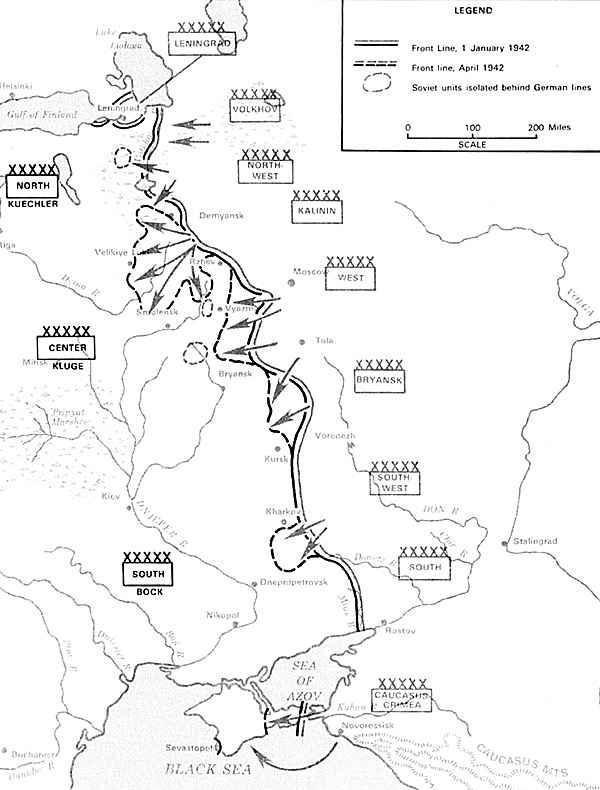

In a curious parallel to Hitler's command actions, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin assumed personal control over the strategic direction of Russian operations in late December. In Moscow, Stalin saw in the Red Army's surprising early success the makings of an even grander counteroffensive to crush the invaders and win the war at one stroke. Pushing Russian reinforcements forward as fast as they could be assembled, Stalin sketched out his new vision for this second stage of the Soviet counteroffensive. The Leningrad, Volkhov, and Northwestern Fronts would bash in the front of Army Group North and lift the siege of Leningrad. The Kalinin, Western, and Bryansk Fronts would annihilate Army Group Center by a colossal double envelopment. In the south, the Soviet Southwestern and Southern Fronts would crush Army Group South while the Caucasus Front undertook amphibious landings to regain the Crimea.

This Red Army avalanche fell on the Germans during the first two weeks of January, thus beginning the second stage of the winter campaign. As during the first stage, German defensive actions benefited from Soviet offensive problems.

A fundamental flaw in the new Soviet operation was the strategic concept itself. Whereas the first-stage counterattacks had been too cautious, the secondstage objectives were far too ambitious and greatly exceeded what could be done with Red Army resources. The attacking Soviet armies managed to penetrate the German strongpoint belt in several

areas, but once into the German rear, the Soviets did not retain sufficient strength or impetus to achieve a decisive victory. Stalin had willfully ignored the suggestions of Zhukov and other Soviet generals that decisive operational success required less grand objectives and greater concentration of striking power.

[114]

Instead, Stalin insisted that the opportunity had come to begin "the total destruction of the Hitlerite forces in the year 1942."

[115]

The advantage to German defensive operations from this conceptual fault was profound. Lacking the necessary reserves to assure the defeat of major breakthroughs,

German armies were spared decisive encirclement and possible annihilation by the

dissipation of Soviet combat power. After breaking through the German strongpoint crust,

Russian attacks eventually stalled on their own for lack of sustenance. On several

occasions, major Soviet formations became immobilized in the German rear, slowly

withering until mopped up by German reinforcements.

For example, the Soviet Second Shock Army, commanded by

General A. A. Vlasov, slashed across the rear of the German Eighteenth Army in January only to become bogged down there in forest and marsh. Unsupplied and unreinforced, Vlasov's nine divisions and several separate brigades remained immobile in the German rear until finally capitulating in June 1942.

[116]

Likewise, the Soviet Thirty-Third Army and a special mobile operational group

composed of General P. A. Belov's reinforced I Guards Cavalry Corps struck deep into the

vitals of Army Group Center near Vyazma only to be stranded there when German troops blocked the arrival of Russian support forces. A similar fate befell the Russian Twenty-Ninth Army near Rzhev.

[117]

In these and other cases, the dispersion of Soviet combat power in pursuit of Stalin's grandiose objectives prevented the reinforcement or rescue of the marooned forces.

Although failing to provoke a general German collapse, these deep drives unnerved the German leadership. As Soviet forces groped toward Army Group Center's supply bases and rail lines of communication in mid-January, the German stand-fast strategy grew less and less tenable. Near despair, General Halder wrote on 14 January that the Fuhrer's intransigent leadership "[could] only lead to the annihilation of the Army."

[118]

The next day, though, Hitler relented by authorizing a belated general withdrawal

of Army Group Center to a "winter line" running from Yukhnov to Rzhev. However, Hitler

imposed stiff conditions on the German withdrawal: all villages were to be burned before

evacuation, no weapons or equipment were to be abandoned, andmost distressing of all to

German commanders with vivid memories of the piecemeal withdrawals in early December -- the retreat was to be carried out "in small steps."

[119]

Indicative of Hitler's penchant for meddling in tactical detail, this last constraint proved particularly painful. Senior German commanders, conforming to Hitler's preference for a more centralized control of operations, dictated the intermediate withdrawal lines to their subordinate divisions. Often, the temporary defensive lines were simply crayon marks on someone's command map, and several units suffered unnecessary casualties in defense of hopelessly awkward positions laid out "on a green felt table" at some higher headquarters.

[120]

Even with this retreat to the winter line, then, it was fortunate for the German cause that the Soviet High Command had obligingly dissipated its forces.

Logistics also hampered Soviet operations to the Germans' benefit. In his eagerness to exploit the December successes, Stalin ordered the January wave of offensives to begin before adequate logistical preparations had been made.

[121]

Zhukov later complained bluntly that, as a result, "[logistical] requirements of the armed forces could not be met as the situation and current tasks demanded." To emphasize this point, the Western Front commander recited his own ammunition supply problems:

The ammunition supply situation was especially bad. Thus, out of the planned ammunition supplies for the first ten days of January, the Front actually received: 82mm mortar shells:1 per cent; artillery projectiles: 20-30 per cent. For all of January: 50mm mortar rounds: 2.7 per cent; 120mm shells: 36 per cent; 82mm shells: 55 per cent; artillery shells: 44 per cent. The February plan was no improvement. Out of 316 wagons of ammunition scheduled for the first ten days, not one was received.

[122]

The general shortage of artillery ammunition directly affected the Red Army's failure to crush the German strongpoint system. Because German defenders regarded Soviet artillery to be an extremely dangerous threat to their strongpoints, the Germans took such measures as were possible to disperse their defensive positions and reduce the

effectiveness of the Russian fire. Even so, that more German strongpoints did not become fatal "man traps" stemmed from the fact that, in general, "the [Soviet] artillery preparation was brief ... due to a shortage of ammunition, and was of little effectiveness."

[123]

Zhukov's units, for example, were limited to firing only one to two rounds per tube

per day during their renewed offensive advances. In a report to Stalin on 14 February,

Zhukov complained that "as shown by combat experience, the shortage of ammunition

prevents us from launching artillery attacks. As a result, enemy fire systems are not

suppressed and our units, attacking insufficiently neutralized enemy positions, suffer very

great losses without achieving appropriate success."

[124]

Misguided tactics also undermined the Soviet artillery's effectiveness. In accordance with faulty prewar tactical manuals, Red Army gunners distributed their pieces as evenly as possible along the front, a practice that prevented the massing of fires against separated strongpoints. Moreover, Russian artillery units frequently located themselves too

far to the rear to be able to provide continuous fire support to attacking units battling through a series of German strongpoints. Instead, according to Artillery General F. Samsonov, "the artillery often limited its operations only to artillery preparation for an attack. All this slowed down the attack, often led to the abatement of the attack, and limited

the depth of the operation."

[125]

These artillery problems were symptomatic of the general lack of Soviet combined arms coordination during this period. Attacking Russian tanks often outdistanced their accompanying infantry, leaving the infantry attack to stall in the face of German obstacles and small-arms fire while the tanks barged past the German strongpoints. Accordingly, the Soviet armor, shorn of its infantry protection, was more vulnerable to German antitank measures. Occasionally, Soviet tanks would halt in full view of German gunners and wait until the assigned Russian infantrymen could catch up, or the tanks would turn around and retrace their path past German positions in search of their supporting foot soldiers.

[126]

Both of these measures played into the hands of German antitank teams. As a

result of the general confusion and lack of tactical cooperation between artillery, infantry,

and armored forces, Soviet commanders conceded the vulnerability of their own assaults to

German counterattack.

[127]

Indeed, the German use of strongpoint tactics preyed mercilessly on these Soviet blunders: German fire concentrations separated tanks and infantry, antitank guns located in depth throughout the strongpoint network picked off the naked Russian armor, and the carefully husbanded German reserves, maneuvering without fear of Soviet artillery interference, delivered the coup de grace by counterattacking the groggy remnants of any Red Army attack.

In an attempt to rectify these shortcomings, Stalin issued a directive to his senior commanders on 10 January that commanded better artillery support, closer tank-infantry cooperation, and--like Zhukov's directive a month earlier to the Western Front--greater use of infiltration and deep maneuver. As a diagnosis, this document showed great insight into

the Red Army's tactical faults. As a corrective measure, this directive (and supplementary orders that succeeded it) came too late, for most Soviet forces were already heavily engaged in the second-stage offensives by the time it was issued. Also, there was little opportunity to reorganize and retrain Soviet units before spring.

[128]

By the end of February, Stalin's great offensive had run its course. German armies,

reinforced at last by the few fresh divisions that Hitler had summoned to the Eastern Front,

reestablished a continuous defensive front, relieved some German pockets isolated behind

Russian lines, and stamped out those Red Army forces still holding out in the German rear.

The front line itself stood as stark evidence of the confused winter fighting: instead of

spanning the front in a smooth arc marred by a few minor indentations, it snaked tortuously

back and forth, its great swoops and bends marking the limits of Russian offensive and

German defensive endurance.

On the German side, the best that could be said of the winter campaign was that

the German Wehrmacht had survived. Strapped by Hitler's strategic rigidity, their strength

exhausted, and lacking proper winter equipment, the German eastern armies had

successfully withstood the two-stage Soviet onslaught using an improvised strongpoint

defensive system. Though fighting as well as could be expected under the circumstances and even incorporating those aspects of their doctrinal Elastic Defense that could be made to fit the situation, German Army officers recognized that they had come within a hairbreadth of disaster. Shaking their heads at their own good fortune, they dimly realized that the survival of the German armies owed as much to Russian

tactical clumsiness and strategic miscalculation as to German steadfastness. This realization clouded German attempts to draw doctrinal conclusions from the winter fighting.

Soviet troops attack a German strongpoint, March 1942

Soviet troops attack a German strongpoint, March 1942

Back to Table of Contents -- Combat Studies Research # 4

Back to Combat Studies Research List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com