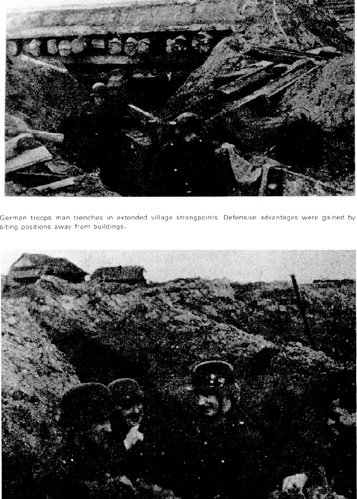

Driven to the shelter of Russian towns and villages as an emergency measure, German troops did their best to fortify these positions against the inevitable Soviet assaults. Defensive techniques varied from division to division according to local conditions and experiences.

Driven to the shelter of Russian towns and villages as an emergency measure, German troops did their best to fortify these positions against the inevitable Soviet assaults. Defensive techniques varied from division to division according to local conditions and experiences.

A German combat group prepares to leave a Russian village with sleds carrying supplies and heavy weapons, February 1942.

A major difficulty, now becoming apparent to German commanders for the first time, was that previous defensive training had been deficient. As one senior officer later wrote, German troops "so far had been inexperienced in this sort of thing. . . . It is surprising indeed how often and to what extent veteran officers, who had already participated in World War I, had forgotten their experiences of those days. The fact that [German] peacetime training shunned everything connected with 'defensive operations under difficult winter conditions' proved now detrimental for the first time [italics in original]." [61]

To compensate for their inexperience, German units shared combat knowhow by exchanging hastily prepared battle reports. An early memorandum of this type, prepared by Fourth Army on 23 January 1942, recounted techniques used effectively by the 10th Motorized Division. Reduced to the strength of a mere infantry regiment, the 10th Motorized Division had for three weeks used a strongpoint defense to defend a fifty-kilometer sector against an estimated seven Red Army divisions.

The 10th Motorized Division's report explained how, in preparing to defend a village strongpoint, officers began by surveying the available buildings to identify those best suited for defensive use. Houses that did not aid in the defense were razed, both to deny the Red Army future use of them as shelter and also to improve German observation and fields of fire. Houses selected as fighting positions were then transformed into miniature

fortresses capable of all-around defense: snow was banked against the outer walls and sheathed with ice, overhead cover was reinforced, and firing embrasures were cut and camouflaged with bedsheets.

When available, multibarreled 20-mm flak guns were integrated into the defense in special positions, which consisted of houses with their roofs purposely torn off, the floors reinforced (to hold the additional weight of guns and ammunition), and the exterior walls covered with a snow and ice glacis to gun-barrel height. These "flak nests" helped keep both Soviet aircraft and infantry at bay. [62]

Russian farming communities were usually located on hills and ridges, and

defensive strongpoints established within them normally had commanding observation and

fire over the surrounding cleared fields. [63]

Defensive combat from such positions was, again according to a 10th Motorized

Division report, primarily "a question of organization," requiring careful use of all available

heavy weapons and artillery. When enemy attacks seemed imminent, German artillery fire

and air attacks (when available) were directed against known and suspected enemy

assembly areas.

As Soviet forces approached the strongpoint, the fire of heavy mortars,

antitank guns, and heavy machine guns joined in. Such fire was carefully controlled, since

experience showed that "it is inappropriate to battle all targets with single artillery pieces and

batteries. It is much more important to strike the most important targets using timely,

concentrated fire to destroy them."

If enemy forces were able to get close enough to launch a close assault against the

fortified buildings, the careful preparations of the defenders kept the odds strongly in their

favor. Any enemy infantrymen who worked their way into a village were either cut down

by interlocking fires from neighboring buildings or wiped out by the counterattacks of

specially designated reserves. Armed with submachine guns and grenades, these reserve

squads were launched against any penetrating enemy troops before they had a chance to

consolidate. [64]

Second, strongpoints sited entirely inside villages virtually conceded control of the

surrounding area to the Red Army. This reduced German reconnaissance and left the

strongpoints susceptible to encirclement or night attack by stealth. (Even in its early report,

the 10th Motorized Division conceded that night attacks were a major problem for village

strongpoints.

Noting that the Russians frequently used night attacks to disrupt the carefully

orchestrated German fire plans, 10th Motorized Division officers felt compelled to keep a

minimum of 50 percent of their strongpoint garrisons on full alert at night "with weapons in

hand" to guard against surprise Soviet assaults. [66])

Finally, most rural Russian villages occupied only a relatively small area, with huts

and houses clustered close together. According to an 87th Infantry Division after-action

report, strongpoints restricted to such congested areas formed "man traps" since they made

ideal targets for Soviet artillery. [67]

The 35th Division's report concurred with this assessment, declaring emphatically

that "the defense of such a [village] strongpoint must be made in the surrounding terrain."

[68]

Likewise, the 7th Infantry Division learned to avoid unduly concentrating troops in

villages even when no other positions had been prepared. [69]

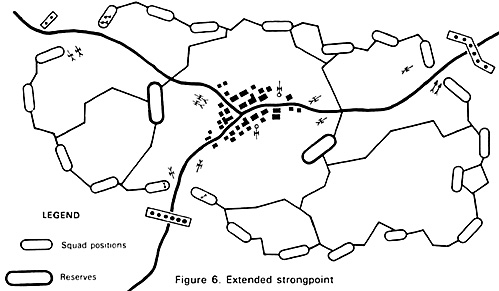

Based on these considerations, German units gradually refined their strongpoint

defenses by pushing defensive perimeters beyond village limits. This helped to conceal the

German positions, increased security against surprise attack, and gave sufficient dispersion

to avoid easy annihilation by Soviet artillery. These extended perimeters also reduced the

distance between neighboring units and made it more difficult for Russian patrols to locate

the gaps between strongpoints. Though tactically sound, the extended perimeter was

accepted only reluctantly by cold and tired soldiers, and "rigorous" measures were

sometimes needed "to convince the troops of the necessity of occupying as uninterrupted a

front line as possible in spite of the cold weather."

[70]

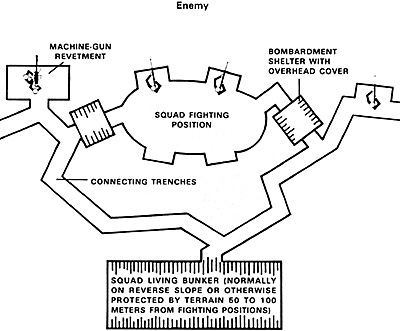

Although each unit developed its own priority of work, the

construction of the outer defensive works usually began with the building of hasty fighting

positions.

Then followed, in varying order, the construction of small, warmed living

bunkers; the improvement of fighting positions; the clearing of communications paths

through the snow; the clearing of fields of fire; and the emplacement of mines and

obstacles. [71]

As a rule, German soldiers kept "living bunkers" that were separate from their

fighting positions (see figure 7). The quarters bunkers, replete with overhead cover, cots,

stoves, and charcoal heaters, were built in sheltered pieces of ground and were connected to the fighting positions by short trenches.

If outpost sentries sounded an alarm, soldiers would scramble from their warm quarters to their battle stations. The living bunkers for forward troops were just large enough to accommodate "the smallest combat unit (squad, machinegun crew, or antitank team).

Thus, these bunkers generally [held] about six men; otherwise they [became] Menschenfallen [man traps] under heavy bombardment." Reserve forces deeper inside the strongpoint perimeter were commonly sheltered in larger, platoon-size bunkers. [73]

Not only did German infantry squads live together in warmed bunkers, but they

also fought together from squad battle positions. These squad positions were normally

protected by individual rifle pits to the flanks and acted as alternate locations for nearby

machine-gun teams. [73]

The use of thick ice walls, armored by pouring water over poncho-covered

bundles of sticks and logs, was a favored method for protecting the fighting positions and

the connecting trenches. [74]

The 35th Division found that the squad battle positions should be uncovered so embattled troops could observe, fire, and throw grenades in all directions. Walk-in bombardment shelters with overhead cover, constructed at intervals throughout the defensive trench system, protected troops from enemy artillery. By day, crew-served weapons were kept inside the living bunkers to protect them from the cold; at night, they were prepositioned outside ready for immediate use. [75]

The Russian winter caused special problems for laying minefields and constructing obstacles. Pressure-activated antipersonnel mines proved to be singularly unreliable. Enemy ski troops could glide over fields of pressure mines without hazard, and the heavy accumulations of snow cushioned the mines so that detonation even by footslogging infantry was uncertain. The snow also smothered the blast of those mines that did explode. Therefore, tripwire-detonated mines were more reliable and more effective than pressure

mines, posing a threat even to Soviet ski troops. (The 87th Infantry Division suggested that tripwires be strung with excessive slack so they would not contract in the extremely cold temperatures and cause the mines to self-detonate.) [76]

Placement of antitank mines was generally restricted to roads and other obvious avenues of approach for armor, as neither mines nor engineers were available in sufficient numbers to lay belts of antiarmor mines elsewhere. Since the Germans used pressure-detonated antitank mines, they ensured that the mines were laid on hard surfaces and that snow did not muffle the explosive effects. In fact, after the blast of buried mines failed to damage the tracks of enemy T-34s, the 35th Division painted its antitank mines white so they could be left nearly exposed on hard-packed road surfaces. [77]

The construction of effective obstacles required some ingenuity. Deep snow, of

course, was a natural obstacle to cross-country movement for troops lacking skis and

snowshoes. (One German attributed the survival of encircled German forces at Demyansk

to the fact that "even the Russian infantry was unable to launch an attack through those

snows." [78])

However, as snowbanks did not always locate themselves to maximum defensive

advantage, the Germans devised effective supplemental barriers. Simple barbed-wire

obstacles were helpful, with a double- apron-style fence being most effective, especially

when coupled with antipersonnel mines and warning devices. Unfortunately, barbed wire

remained generally in short supply due to the ruinous German logistical system, and wire

fences could be covered by drifting snow. Thus, the 7th Infantry Division believed that its

few flimsy wire obstacles were valuable only for the sake of morale and early warning. [79]

To compensate for the barbed-wire shortage, German troops contrived a variety of

expedient entanglements. Some units gathered large quantities of harvesting tools from

Russian villages and fashioned "knife rest" obstacles consisting of sharpened scythe blades

supported by wooden frames. Even when covered by snow drifts, these nasty blade fences

impeded or injured Soviet infantrymen wading through deep snow toward German

positions. [80]

In and near wooded areas, the Germans felled trees to make abatis-type barriers. Snow walls, measuring two to three

meters high and thick, were built -- mostly with civilian labor -- to impede Russian tanks."

[81] Some German units tried to keep Soviet forces at arm's length by burning down all Russian villages forward of their own positions. Denied the warmth and shelter of these buildings, Red Army troops would have to spend their nights sheltered some distance away from the German lines and could attack only after a lengthy approach march. [82]

However fortified and protected by barricades, the village strongpoints still occupied only a small fraction of the German front line. Thus, although German officers continued to use the doctrinal term "HKL" (Hauptkampflinie or main line of resistance) to describe the German forward trace, a line existed only in a general sense. Recalling the large

gaps between strongpoints, the former commander of the 6th Infantry Division later complained that even the use of "the term HKL was misleading. The HKL was a line drawn on a map, while on the ground there stood only a weak strongpoint-type security zone." [83]

The Sixth Army's war diary also noted this discrepancy, describing the German

winter positions as a mere "security line" of strongpoints that did not amount to an "HKL in

the sense envisioned by Truppenfiihrung." [84]

The intervals between strongpoints were the Achilles' heel of the German

defensive system. Russian forces seemed to have an uncanny ability to locate unoccupied

portions of the German front. If left unmolested, Red Army troops would maneuver

through these gaps to encircle individual strongpoints. If cut off from outside aid and

resupply, the besieged German defenders could then be forced either to capitulate or to

conduct a desperate breakout.

As combat experience revealed the gravity of these problems, the Germans

became more determined in their efforts to exert some control over the space between

strongpoints. The 5th Panzer Division, discussing the problems of strongpoint defense in its

after-action report, concluded that "constant control of the territory between builtup areas

(strongpoints) is of decisive importance. Only thus can envelopment attempts by the enemy

be promptly frustrated." [86]

Complete control of the entire front was, of course, inherently beyond the capacity

of the strongpoint garrisons. Where adjacent strongpoints could adequately observe the

surrounding open spaces, German units used artillery and mortar fire to disrupt large-scale

Soviet infiltration. However, darkness, poor weather, wooded terrain, and distance all

reduced the German ability to detect and to interdict clandestine Soviet movement by fire.

For these reasons, as the 87th Infantry Division reported, "the closing of gaps by fire alone

[was] not always sufficient." [87]

German patrols also stalked the gaps between strongpoints, trying at least to detect,

if not to prevent, Russian encroachment. Even this limited patrolling strained German resources, particularly at night: few strongpoint contingents could confidently spare many infantrymen for nocturnal patrols for fear of Soviet night attacks on the strongpoints themselves.

[88]

German commanders, therefore, came to realize that neither artillery fire nor ground patrols could thwart determined Russian efforts to pass between widely separated strongpoints.

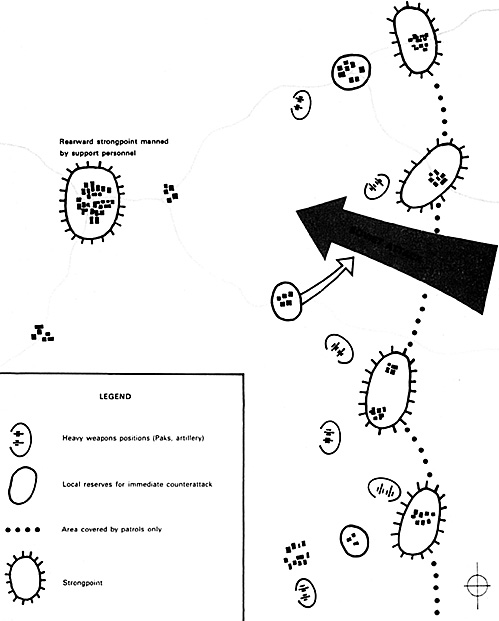

Where strongpoints were sited closer together, the Germans relied on traditional doctrinal methods to expel Russian penetrations. With the bulk of their modest infantry strength confined to strongpoints, German forces could not exercise small-unit maneuver as described in Truppenfuhrung; however, the Elastic Defense principles of depth, firepower, and counterattack effectively neutralized all but the most overwhelming Soviet attacks (see figure 8).

Since infantry strength was so limited, defensive depth had to be improvised. One technique was to arrange the forward strongpoints checkerboard style so that backup strongpoints guarded the gaps between advanced positions. The 331st Infantry Division, in fact, reported that one of the essential conditions for a successful strongpoint defense was

that the redoubts be staggered one behind another to create defensive depth of sorts." [89]

In a memorandum reflecting its own winter experiences, the 98th Division

described how this arrangement entangled enemy breakthroughs "in a net of strongpoints." [90]

Where sufficient forces allowed the luxury of this technique, the strongpoint system most nearly resembled the defense in depth set forth in Truppenfuhrung. Insufficient numbers of troops or broad unit frontages often prevented the overlapping of combat strongpoints in depth, however. Another expedient method of generating defensive depth--and the one specifically ordered by Hitler's 26 December directive--was to convert all rearward logistical installations into additional

strongpoints. Though manned only by supply and service personnel (occasionally augmented by Landeschutz security units composed of overage reservists), these strongpoints prevented the Soviets from freely exploiting tactical breakthroughs. Such support strongpoints also protected the valuable logistical sites from surprise attack and

served as rallying points for German personnel separated from their units in the confusion of battle. [91]

One other technique for giving depth to the German defense was to array heavy weapons (light "infantry" howitzers, antitank guns, flak guns, artillery pieces) and artillery observers in depth behind the forward strongpoints. Enemy forces penetrating beyond the strongpoint line could thus be continuously engaged by direct and indirect fire to a

considerable depth. (The 197th Infantry Division actually recommended graduating artillery assets for a distance of five kilometers behind the main line of resistance.) Though weakening the direct-fire capabilities of the forward strongpoints somewhat, this technique did not require the displacement of the snowbound German guns in order to fire on

penetrating Soviets. Furthermore, the fortified gun positions also served as additional pockets of resistance against further Russian advance.

[92]

The 87th Division saw in this a confirmation of prewar doctrinal methods, noting that "the arrangement of heavy weapons and their deployment in depth according to the tactical manuals proved successful."

[93]

Even though this technique complied with doctrine, under the circumstances it was

a desperate expedient because it risked sacrificing the precious German artillery simply to

contain ground assaults.

The German heavy weapons were far more valuable for their ability to smash

advancing Soviet formations by fire. By careful fire control, German commanders used

their concentrated firepower to slow, disrupt, and occasionally even destroy Soviet

penetrations outright. As explained in one after-action report, "Rapid concentration of the

entire artillery on the enemy's main effort is decisive." [94]

To that end, German divisions meticulously integrated the fires of all major direct- and indirect-fire weapons (including infantry mortars and heavy machine guns), as well as

the fires of neighboring units, into a single division fire plan. This prearranged fire plan was

then executed on order of designated frontline commanders so that attacking Russian troops

were suddenly ripped by simultaneous blasts of concentrated artillery and small-arms fire.

The 35th Division explained that intense flurries of shells falling on Soviet assault units "just

at the moment of attack [could] stampede even the best troops." [95]

However clever the Germans were in fabricating defensive depth and however skillfully they brandished their limited firepower, determined Soviet attacks could not be vanquished by these means alone. More often, depth and firepower were mere adjuncts to the counterattack, the third traditional ingredient of German defensive operation, German

unit combat reports unanimously cited immediate, aggressive counterattacks (Gegenstosse), even when conducted using limited means, as the best way to defeat Russian penetrations. Deliberate counterattacks (Gegenangriffe) -- which doctrinally were those more carefully coordinated counterblows using fresh units -- were regarded as less effective due to the shortage of suitable uncommitted forces and the German lack of winter mobility. The operations officer of the 78th Division stated that "a Gegenstoss thrown immediately against an enemy break-in, even if only in squad strength, achieves more than a deliberate counterattack in company or battalion strength on the next day." [96]

However, a fine line existed between aggressiveness and recklessness, and few German units could afford to suffer even moderate personnel losses from an ill-conceived counterattack. Consequently, the 35th Division counseled that, where the Russians had been allowed any time at all to consolidate or where the depth of the enemy penetration made immediate success unlikely, German reserves were to be used only to contain the enemy rather than to be squandered in weak or uncoordinated piecemeal counterattacks. [97]

The immediate counterattacks were normally performed by small reserve contingents positioned in villages behind the forward strongpoints. According to one division commander, these forces were assembled despite the consequent weakening of the forward positions. The strength of these counterattack detachments varied in that some units held as

much as one-third of their total strength in reserve, while others made do with smaller forces. Invariably, however, the counterattack forces were given as much mobility as possible. Where available, skis and snowshoes were issued to the reserve units; where these were unavailable, Russian civilians were put to work trampling paths through the snow along likely counterattack axes. To ensure the proper aggressive spirit, some units

disregarded unit integrity and assembled their reserves from "especially selected, capable, and daring men." [98]

These desperadoes were armed "for close combat" with machine pistols and hand grenades. For maximum shock effect, these counterattack forces were launched against the open flanks of enemy penetrations, preferably in concert with heavy supporting fires from all available weapons.

[99]

Thus, though the strongpoint defensive system did not conform exactly to the doctrine in Truppenfuhrung, the German expedient methods bore the unmistakable imprint of traditional principles in their use of depth, firepower, and especially counterattack. General Maximilian Fretter-Pico, who served through the 1941-42 winter battles with the 97th Light Infantry Division, described the German improvisations in words that captured

the essential spirit of the Elastic Defense: "These defensive battles show that an active defense, well-organized in the depth of the defensiue zone and using every conceivable means to improvise combat power, can prevent a complete enemy breakthrough. A defense must be conducted offensively even in the depth of the defensive zone in order to weaken [enemy] forces to the maximum extent possible [italics in original]."

[100]

In many cases, the strongpoint style of defense did achieve remarkable successes against great odds. Fretter-Pico's division, for example, held its own against some 300 separate Soviet attacks between January and March 1942, with its subordinate units executing in that time more than 100 counterattacks. [101]

Other units were less successful, however, with some divisions being almost completely torn to pieces by the Russian counteroffensives. Therefore, the varied effectiveness of the German defensive expedients is best understood in the context of the overall strategic situation.

A German machine-gun team defends a village strongpoint, February 1942. A destroyed Soviet tank is in the background.

A German machine-gun team defends a village strongpoint, February 1942. A destroyed Soviet tank is in the background.

During this winter fighting, German units soon realized that strongpoints confined

to small villages had serious drawbacks as well as advantages. For one thing, Soviet armor posed a deadly threat to house-based defenses. Since camouflage could not hide buildings, Russian tanks had little difficulty in identifying and engaging the German positions concealed therein. Moreover, if successful in driving the Germans from

their building shelters and into the open, the enemy tanks could slaughter the fleeing

Germans almost at leisure. [65]

During this winter fighting, German units soon realized that strongpoints confined

to small villages had serious drawbacks as well as advantages. For one thing, Soviet armor posed a deadly threat to house-based defenses. Since camouflage could not hide buildings, Russian tanks had little difficulty in identifying and engaging the German positions concealed therein. Moreover, if successful in driving the Germans from

their building shelters and into the open, the enemy tanks could slaughter the fleeing

Germans almost at leisure. [65]

Within these extended strongpoints, command and support personnel, artillery, and

reserve detachments were normally located in and around the builtup area itself An outer

defensive perimeter, consisting of interconnected infantry fighting positions, encircled this

central core (see map at right).

Within these extended strongpoints, command and support personnel, artillery, and

reserve detachments were normally located in and around the builtup area itself An outer

defensive perimeter, consisting of interconnected infantry fighting positions, encircled this

central core (see map at right).

Figure 7. German squad fighting positions and living bunker. Living bunkers were sturdily built and had strong overhead covers. They normally contained cots, charcoal stoves, and wooden flooring, and served as a field barracks for German troops.

Figure 7. German squad fighting positions and living bunker. Living bunkers were sturdily built and had strong overhead covers. They normally contained cots, charcoal stoves, and wooden flooring, and served as a field barracks for German troops.

A sketch of inside a German living bunker.

A sketch of inside a German living bunker.

A German reconnaissance patrol, supported by a sled-borne machine gun, prepares to depart a village strongpoint, January 1942

A German reconnaissance patrol, supported by a sled-borne machine gun, prepares to depart a village strongpoint, January 1942

Alternatively, Soviet units could force their way between

strongpoints and move directly against valuable objectives deeper in the German rear. While

posing a less immediate tactical threat to German regiments and divisions, this option imperiled the fragile

German logistical network and, indirectly, the long-term survival of entire German armies.

The Red Army even found ways to exploit gaps in sectors where current Soviet plans did

not call for major operations. Russian press gangs brazenly shuttled through a large wooded

gap between Demidov and Velikiye Luki, for example, to raise Red Army conscripts in the

German rear. In other areas, the Soviets used openings in the German front to convey

cadre, weapons, and equipment to fledgling partisan bands behind the German lines. [85]

Alternatively, Soviet units could force their way between

strongpoints and move directly against valuable objectives deeper in the German rear. While

posing a less immediate tactical threat to German regiments and divisions, this option imperiled the fragile

German logistical network and, indirectly, the long-term survival of entire German armies.

The Red Army even found ways to exploit gaps in sectors where current Soviet plans did

not call for major operations. Russian press gangs brazenly shuttled through a large wooded

gap between Demidov and Velikiye Luki, for example, to raise Red Army conscripts in the

German rear. In other areas, the Soviets used openings in the German front to convey

cadre, weapons, and equipment to fledgling partisan bands behind the German lines. [85]

German infantry counterattacking, January 1942. Note the lack of winter camouflage overgarments.

German infantry counterattacking, January 1942. Note the lack of winter camouflage overgarments.

Back to Table of Contents -- Combat Studies Research # 4

Back to Combat Studies Research List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com