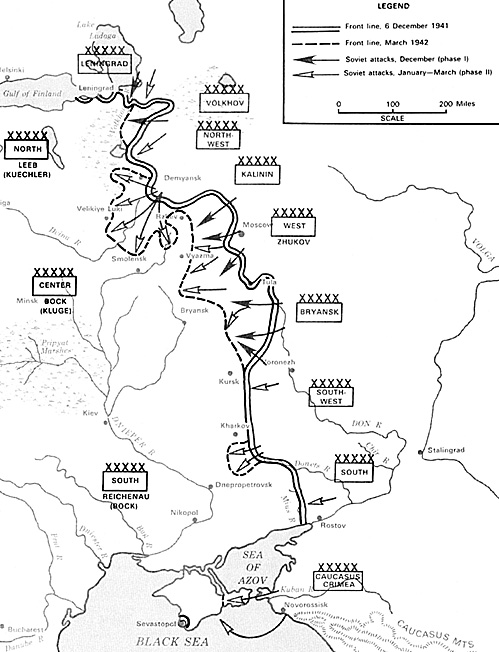

The Russo-German War entered its second major phase in December 1941.

During the previous five months, the Germans had held the strategic initiative, but on 6

December, the Red Army seized the initiative, counterattacking first against Army Group

Center and later against all three German army groups. Lasting through the end

of February, these attacks upset the calculations of Fuhrer Directive 39, which had

assumed that the front would remain quiescent until the following spring.

The Russo-German War entered its second major phase in December 1941.

During the previous five months, the Germans had held the strategic initiative, but on 6

December, the Red Army seized the initiative, counterattacking first against Army Group

Center and later against all three German army groups. Lasting through the end

of February, these attacks upset the calculations of Fuhrer Directive 39, which had

assumed that the front would remain quiescent until the following spring.

The Soviet winter counteroffensives prompted significant changes to German strategy and tactical methods. These alterations emerged during the winter fighting and helped shape the German defensive practices that were used throughout the remainder of the war.

At the strategic level, the December crisis on the Eastern Front caused Hitler to override his military advisers' recommendations by enjoining a facesaving no-retreat policy that callously risked the annihilation of entire German armies. His patience with independent-minded officers finally at an end, the German dictator then followed this strategic injunction with a purge of the German Army's senior officer corps that left the Fuhrer in direct, daily control of all German military activities.

These events had ominous long-term implications in that Hitler's personal command rigidity, together with his chronic insistence on "no retreat" in defensive situations, eventually corrupted both the style and substance of German military operations.

The winter of 1941-42 left its mark on German defensive tactics as well. During the defensive battles from December to February, German attempts to conduct a doctrinal Elastic Defense were generally unsuccessful. Instead, German units gradually fell to battling Soviet attacks from a chain of static strongpoints. This defensive method was based on tactical expedience and was successful due as much to Soviet disorganization as to German steadfastness.

Standing Fast

The German High Command was slow to appreciate the magnitude of the Soviet winter counteroffensive. For weeks prior to the Russian onslaught, German units had been reporting incessant enemy counterattacks during their own drive toward Moscow. So routine had these counterattacks become that German analysts failed to recognize

immediately the Russian shift from local counterattacks to a general counteroffensive. Since the Germans had seemingly ruled out large-scale offensive operations for themselves due to

heavy losses, supply difficulties, and severe weather conditions, they supposed the Russians would do the same. In fact, the intelligence annex supporting Fuhrer Directive 39 discounted the Red Army's ability to mount more than limited attacks during the coming winter. [1]

High-level German leaders also underestimated the abject weakness of their own

units. The Taifun offensive had overextended the German armies in the east, and their

spent divisions lay scattered like beached flotsam from Leningrad to Rostov. As a

discouraged General Guderian wrote on 8 December: "We are faced with the sad fact that

the Supreme Command has overreached itself by refusing to believe our reports of the

increasing weakness of the troops.... [I have decided] to withdraw to a previously selected

and relatively short line which I hope that I shall be able to hold with what is left of my forces. The Russians are pursuing us closely and we must expect misfortunes to occur." [2]

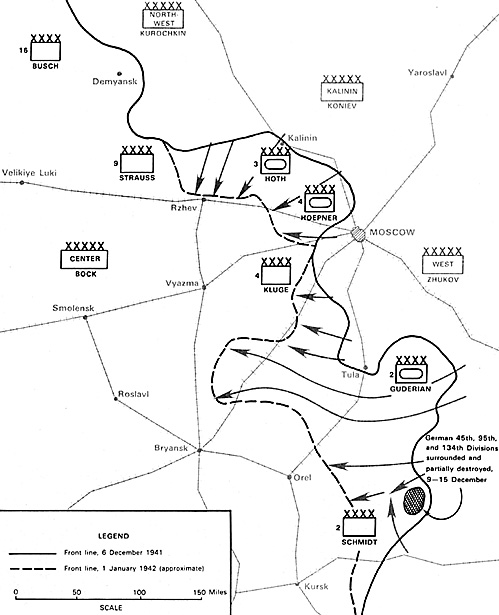

The most exposed forces were the 3d and 4th Panzer Groups north of Moscow

and Guderian's Second Panzer Army south of the Russian capital. Occupying salients

formed during Operation Taifun, these exposed panzer and motorized divisions experienced

a cruel reversal. Once again, offensive success had turned into defensive peril for the

panzers, as the formations most heavily beset by Soviet attacks were also those least able to

sustain a positional defense.

Caught off balance by the Soviet counteroffensive, the Germans lacked any real concept for dealing with the deteriorating situation on the central front. The chief of the German Army General Staff wrote in his diary that "the Supreme Command [Hitler] does not realize the condition our troops are in and indulges in paltry patchwork where only big decisions could help. One of the decisions that should be taken is the withdrawal of Army Group Center." [4]

Still smarting from Army Group South's earlier abandonment of Rostov, however, Hitler was unwilling to countenance any such retreat. Instead, German countermeasures during the first two weeks of the Russian offensive were reminiscent of the frantic half

measures taken during the summer defensive crises at Yelnya and Toropets: minor local

withdrawals and piecemeal attempts to contain Soviet breakthroughs. For example, the

hasty withdrawal of Second Panzer Army's beleaguered divisions from the area east of Tula

was done on Guderian's own initiative and not as part of a coordinated general plan.

Although these measures reduced the immediate likelihood that exposed units

would be cut off and destroyed, the fundamental German strategic problem was not

addressed. The thin lines of exhausted German troops seemed to be on the verge of

collapse, few reinforcements were available, and puny local countermeasures merely invited

greater danger. For instance, even as Guderian's forces were recoiling from Tula, gaps

opened between his units, and sizable Russian forces poured into the German rear. [5]

Then, between 9 and 15 December, a massive Soviet attack on Guderian's right

flank overran and virtually annihilated the German Second Army's 45th, 95th, and 134th Infantry Divisions. [6]

This complete destruction of German divisions was unprecedented in World War II

and an unmistakable omen of impending disaster. By the third week of December, deep

Soviet penetrations on both flanks of Bock's army group threatened to ripen into a double

envelopment of the entire German central front. After touring the splintered German lines,

ailing Field Marshal von Brauchitsch confessed to Halder that he could "not see any way of

extricating the Army from its present predicament." [7]

In fact, only two alternatives offered an escape from the deepening crisis. One

choice was to conduct an immediate large-scale withdrawal, trusting that German forces

could consolidate a rearward defensive line before Soviet pursuit could inflict decisive

losses. The other choice was to stand fast and weather the Soviet attacks in present

positions. Neither course of action guaranteed success, and each was fraught with

considerable risk.

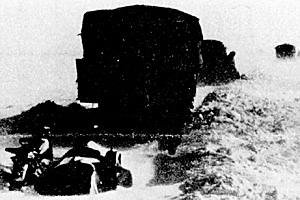

A winter retreat would cost the Germans much of their artillery and heavy

equipment, which would have to be abandoned for lack of transport. Because of Hitler's

procrastination in November, no rearward "east wall" defensive line had been prepared;

therefore, a withdrawal promised little improvement over the tactical situation the Germans

already faced. [8]

Too, as already shown on Guderian's front south of Moscow, retrograde

operations could easily lead to an even greater crisis if enemy units managed to thrust between the retreating German columns. Finally, a retreat through the Russian winter conjured up the shade of Napoleon's 1812 Grande Armie. Though morale in the depleted German divisions still remained generally intact despite the harsh conditions, German officers fearfully reminded each other of the sudden moral collapse that had turned the French retreat into a rout nearly a century and a half before.

[9]

The alternative seemed even more desperate. A continued defense from present positions could succeed only if German defensive endurance exceeded Russian offensive endurance--a slim prospect considering the exhausted state of the German forces. The

chances for success were best on the extreme northern and southern wings, where the

Leningrad siege works and the Mius River line offered some protection. Between these two

poles, however, a stand-fast defense would surely cost the Germans heavily. The absence

of reserves and the lack of defensive depth ensured that some units would be overrun or

isolated during the winter. Moreover, this course of action forfeited the possibility of a new

German offensive in the central sector the following spring or early summer, since surviving

German divisions of Army Group Center would require substantial rebuilding.

Conditioned by their professional training to weigh risks carefully and to conserve

forces for future requirements, German commanders and staff officers preferred the

potential dangers of a winter retreat to the certain perils of standing fast. Guderian, for

example, regarded "a prompt and extensive withdrawal to a line where the terrain was

suitable to the defense ... [to be] the best and most economical way of rectifying the

situation," while Brauchitsch and Halder agreed that "Army Group [Center] must be given

discretion to fall back ... as the situation requires."

[10]

In anticipation that this course of action would be followed, Russian civilians and

German labor units were hurriedly pressed into work on a rearward defensive line running

from Kursk through Orel to Gzhatsk. [11]

Once again, Adolf Hitler confounded the plans of his military advisers. Hitler

watched the disintegration of the German front with great dismay and convinced himself

that each retreat simply added momentum to the Soviet offensive. On 16 December, the

German dictator telephoned Bock to order Army Group Center to cease all withdrawals and

to defend its present positions. German soldiers would take "not one single step back." At a

late night conference the same evening, Hitler extended the stand-fast order to the entire

Eastern Front. A general withdrawal, he declared, was "out of the question." [12]

Hitler marshaled both real and fanciful arguments to justify his decision. Citing

information collected by his personal adjutant, Colonel Rudolf Schmundt, Hitler ticked off

the disadvantages of retreat: German units were sacrificing artillery and valuable equipment

with each withdrawal, no prepared line existed to which German forces could expeditiously

retire, and "the idea to prepare rear positions" amounted to "drivelling nonsense." [13]

Furthermore, Hitler argued, attempts to create fallback positions weakened the resolve of

the fighting forces by suggesting that current positions were expendable. All of these

arguments were at least partially correct, even if senior military officers preferred to

discount them.

However, Hitler's rationalizations went even further. Contrary to the visible

evidence, Hitler insisted that the Russians were on the verge of collapse after suffering

between 8 and 10 million military casualties. (This estimate exaggerated Soviet losses by

almost 100 percent.) The Red Army artillery, he claimed, was so decimated by losses that it

no longer existed as an effective arm--a claim for which there was no evidence whatsoever.

Hitler asserted that the enemy's sole asset was the superior numbers of soldiers, an

advantage of no real value since they were "not nearly as good as ours."

In a strange twist of logic, Hitler even argued that the enormously wide frontages held by German

divisions proved the enemy's weakness, since otherwise the Soviets would have exploited

this vulnerability to a greater extent than they had already done. (Coming at a time when

the entire German front was threatening to give way in the face of Soviet offensive

pressure, this claim must have seemed totally outrageous.)

[14]

One major factor that affected Hitler's decision went largely unspoken by the

dictator. Tyrants, it is said, fear nothing so much as ridicule, and Adolf Hitler feared the

embarrassment that retreat would cause to the Reich's-and to his own-military prestige.

Moreover, on 11 December, Hitler had recklessly declared war on the United States, a

move that unnecessarily compounded Germany's military problems. Under the

circumstances, the spectacle of German armies in unseemly retreat before Russian

Untermenschen (subhumans) would have been a serious blow to Hitler's credibility.

Therefore, German soldiers were exhorted to "fanatical resistance" in place "without regard

to flanks or rear." [15]

Having again rejected the recommendations of his military advisers, Hitler decided

to rid himself once and for all of uncooperative senior officers. Not only would this end the

tugs-of-war between Hitler and the Army High Command over military strategy, but it

would satisfy Hitler's desire to curb the enduring independence of the German Army's officer corps as well.

Adolf Hitler had an irrational mistrust of the aristocratic, apolitical officers who held most of the high positions in the German Army. Their professional aloofness and political indifference had long irritated Hitler, who regarded them as obstacles to his own strategic visions and his personal power. Since becoming chancellor in 1933, he had skillfully worked to curtail the army's

independence. When the aged Weimar President von Hindenburg died in 1934, Hitler

suborned an oath of personal loyalty from all members of the armed forces, a step that

exceeded the doomed Weimar Republic's constitutional practice.

In 1938, Hitler engineered the disgrace and removal of Field Marshal Werner von

Blomberg and General Werner Freiherr von Fritsch, who were respectively the minister of

war and commander in chief of the army. At that time, Hitler absorbed the duties of war

minister into his own portfolio as Fuhrer and created a new joint Armed Forces High

Command (OKM, which diluted the traditional autonomy of the German Army. Hitler then

staffed the senior OKW posts with sycophants like General (later Field Marshal) Wilhelm

Keitel and General Alfred Jodl so that the OKW amounted to little more than an executive

secretariat for Hitler and an operational impediment to the Army High Command (OKH).

As his knowledge of military matters grew during the war, Hitler overruled with greater

frequency and confidence the campaign advice of his army advisers. During Barbarossa, the

army's resistance to Hitler's interference repeatedly antagonized the Fuhrer, and so he

resolved to purge troublesome officers. [16]

Field Marshal von Brauchitsch, the German Army's commander in chief, was

among the first to follow Rundstedt into retirement. Weakened by a heart attack in

November, Brauchitsch had neither the moral courage nor the physical strength to resist the

Fuhrer's trespasses. Hitler made no secret of his growing disdain for the ill field marshal,

subjecting him to humiliating tonguelashings and treating him openly as a gold-braided

"messenger boy." [17]

On 19 December, Hitler finally sacked Brauchitsch and took over the position of

army commander in chief.

The timing of Brauchitsch's relief was masterful. Although not stated so officially,

Brauchitsch was made the scapegoat for the failure of Barbarossa and for the winter crisis

on the Eastern Front. Hitler himself propagated this view to his inner circle, referring to

Brauchitsch as "a vain, cowardly wretch who could not even appraise the situation, much

less master it. By his constant interference and consistent disobedience he completely

spoiled the entire plan for the eastern campaign." [18]

Although Brauchitsch had been a weak and relatively ineffective army commander

in chief, the real issue in his relief was not military competence but political loyalty and

personal subservience. Lest this lesson be misunderstood, Hitler pointedly informed Halder

that "this little affair of operational command is something that anybody can do. The

Commander-in-Chief's job is to train the Army in the National Socialist idea, and I know of

no general who could do that as I want it done. For that reason I've decided to take over

command of the Army myself." [19]

As soon as Brauchitsch was out of the way, Hitler then turned his wrath on balky

field commanders. With Hitler directly supervising their operations, frontline officers no

longer enjoyed the insulation previously provided by Brauchitsch. Furthermore, with the

Fuhrer doubling as the army commander in chief, military subordination effectively became

synonymous with political allegiance. Officers who too candidly criticized Hitler's strategic

designs or commanders who took independent action at variance with Hitler's instructions

were implicitly guilty of affronting the Fuhrer's personal authority.

Whereas during the war's earlier campaigns such independence might have gone unremarked or

unchecked, henceforth such actions might lead to swift relief or even worse.

Hitler, bent on a personal vendetta against the German Army's leaders, was given

ample opportunity to make examples of offending officers during the winter defensive crisis.

Suffering from failing health, Field Marshal von Bock had already lost the Fuhrer's

confidence over Army Group Center's failure to storm Moscow. When Bock persisted in

predicting disaster unless allowed to retreat, he was abruptly retired on 20 December.

General Guderian evaded orders to stand fast because such actions would endanger his

Second Panzer Army and, after a tense face-to-face meeting with Hitler on 20 December,

was relieved from active duty on 26 December.

[20]

General Erich Hoepner, like Guderian an aggressive panzer leader, enraged Hitler

in early January by ordering units of his Fourth Panzer Army [Panzer Groups 3 and 4 were

redesignated panzer armies on 1 January 1942.] to retreat westward to avoid encirclement.

Hoepner was summarily relieved of his command, and Hitler ordered that Hoepner be

stripped of all rank and privileges, including the right to wear his uniform in retirement. [21]

Strauss, the Ninth Army commander who had directed the German defense against

Timoshenko's attacks in August and September, was cashiered a week after Hoepner for

being overly pessimistic in his reports.

Field Marshal von Leeb, the commander of Army Group North, found his prewar defensive theories swept aside by Hitler's insistence on a rigid defense. When Leeb explained that a dangerous and unnecessary salient near Demyansk should be abandoned to free badly needed reserves, Hitler

countered by arguing that such salients were, in fact, beneficial since they tied down more Russian than German forces. Leeb, "being unable to subscribe to this novel theory," was thus relieved on 17 January.

[22]

Army and army group commanders were not Hitler's only targets. In fact, during the

1941-42 winter, he relieved more than thirty generals and other high-ranking officers who

had been corps commanders, division commanders, and senior staff officers. [23]

Hitler also took other steps to secure control over the German Army. Disregarding

seniority and even combat experience, Hitler elevated officers of unquestioning loyalty

(such as General Walter Model) or officers of known Nazi sympathies (such as Field

Marshal Walter von Reichenau) to senior positions. (Model replaced Strauss as commander

of Ninth Army, while Reichenau succeeded Rundstedt at Army Group South. Reichenau's

previous position as Sixth Army commander was filled by the loyal but unimaginative

General Friedrich Paulus, an energetic staff officer whose unflinching obedience led to

tragedy at Stalingrad a year later.)

To ensure close future control over promotions and assignments, Hitler promoted

Schmundt, his personal adjutant, to general and placed his former aide in charge of the

army personnel office. In one further step to cement his authority, Hitler forbade voluntary

resignations, thereby denying the German officer corps the traditional soldierly protest

against unconscionable commands. [24]

While the removal of unruly senior officers made the German Army more docile,

these turnovers adversely affected German military performance in three ways.

First, the cashiering of so many field commanders in the midst of desperate

defensive fighting disrupted the continuity of German operations. The newly appointed

leaders, who frequently brought with them new chiefs of staff, normally required an

adjustment period before they could discharge their new duties with complete confidence.

In fact, some of the replacements could not make the adjustment at all. General Ludwig

Kubler, who replaced Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge as Fourth Army commander when

Kluge replaced Bock, found Hitler's stand-fast strategy intolerable and requested his own

relief barely a month after assuming command. [25]

The net effect of all this turmoil was to minimize bold initiatives at the front and to

concede virtually all strategic and operational control to the Fuhrer by default.

Second, by sweeping away those officers who had the temerity to challenge

Hitler's strategic views, an important source of advice and assessment was silenced. For the

remainder of the war, responsible criticism of the Fuhrer's designs was muted by the threat

of punishment. Therefore, for the next three years, German military strategy lurched from

disaster to disaster due mainly to Hitler's having banished or intimidated into silence those

whose courage, skill, and judgment best qualified them to act as independent advisers.

Finally, by removing so many senior leaders and by inserting himself into the chain

of command as army commander in chief, Hitler profoundly altered the command

philosophy of the German Army.

For generations, commanders in the Prussian and German Armies had been schooled to direct operations according to the principle of Auftragstaktik. This principle constrained commanders to giving broad, mission-oriented directives to their juniors, who were then allowed maximum latitude in accomplishing their assigned tasks. Senior leaders trusted

implicitly in the professional discretion of their subordinates, and German operations

characteristically evinced a degree of imagination, flexibility, and initiative matched by few

other armies. So deeply ingrained was this philosophy that actions contrary to orders were

seldom regarded as disobedience, but rather as laudable displays of initiative and

aggressiveness. According to a German military aphorism, mules could be taught to obey

but officers were expected to know when to disobey. [26]

Hitler's rigid and overbearing insistence on the literal execution of all orders

corrupted Auftragstaktik. That Hitler, the "Bohemian corporal," did not understand this

system or, more likely, that he had no patience for it was demonstrated early in the

Barbarossa campaign. Halder diagnosed Hitler's leadership style as lacking "that confidence

in the executive commands which is one of the most essential features of our command

organization, and that is so because it fails to grasp the coordinating force that comes from

the common schooling of our Leader Corps." [27]

The harm done to the German command philosophy was not confined to upper

echelons only, however. Hitler's stifling, obedience-oriented style was transmitted throughout the German Army so that operations at all levels suffered its stifling effects. Senior field commanders, themselves answerable to the implacable Fuhrer, were thus pressed to control more closely the operations of their own subordinates. This corrosive process was abetted by two features of the World War II battlefield. The first was modern radio communications, which enabled senior commanders to direct even

remote combat actions.

This not only invited greater interference, but spawned timidity at lower levels by

conditioning subordinates to seek ratification of their decisions from their superiors before

acting. Second, the chronic lack of German reserve units--a circumstance particularly

pervasive on the Eastern Front--reduced the ability of senior commanders to rectify the

mistakes of subordinates and thus encouraged the centralization of battle direction at higher

levels.

As General Frido von Senger und Etterlin, a veteran of both the Russian and Mediterranean theaters, wrote after the war:

Reserves enable the commander to preserve a measure of independence. He may feel

obliged to report his decisions, but as long as his superior authority has his own reserves with

which to influence the general situation, that authority will only be too ready to leave the

subordinate commander to use his as he thinks best. If the forces shrink so much that these

normal reserves are not available ... then the forces so detailed are put at the disposal of the

highest commander in the area, while the local commanders ... can no longer expect to

exert any decisive influence on the operations. [28]

German leaders were therefore driven to a more and more centralized style of

command. Hitler's insistence on literal obedience restricted independence from above, while

the lack of battlefield reserves reduced the latitude for initiative from below. The result was

a decline in the flexibility that had been traditional in German armies for over a century.

Because real operational flexibility no longer existed in the German Army from the

winter of 1941-42 onward, German defensive actions on the Russian battlefield were

adversely affected. Hitler's orders to the German Army to stand fast established the framework of German defensive strategy. The cashiering of recalcitrant senior officers gave authority to that strategy and gradually narrowed the discretionary latitude of subordinate leaders to act independently. It remained for the combat units themselves, coping as best as they could with dreadful weather and a tough enemy, to give substance to the German defense.

The greatest immediate danger loomed on Army Group Center's front. Committed to offensive action until swamped by the Soviet counterblow, the divisions of Field Marshal von Bock's army group had prepared few real defensive works. On 8 December-the same day that Guderian on his own initiative had ordered his Second Panzer Army to begin withdrawing-Bock assessed that his army group was incapable of stopping a strong counteroffensive. [3]

The greatest immediate danger loomed on Army Group Center's front. Committed to offensive action until swamped by the Soviet counterblow, the divisions of Field Marshal von Bock's army group had prepared few real defensive works. On 8 December-the same day that Guderian on his own initiative had ordered his Second Panzer Army to begin withdrawing-Bock assessed that his army group was incapable of stopping a strong counteroffensive. [3]

German equipment abandoned outside Moscow.

German equipment abandoned outside Moscow.

Hitler feared the loss of valuable equipment during a general winter retreat.

Hitler feared the loss of valuable equipment during a general winter retreat.

Two senior commanders relieved by Hitler: Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch (left), commander in chief of the

German Army, and General Heinz Guclerian (right), commander of the Second Panzer Army.

Two senior commanders relieved by Hitler: Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch (left), commander in chief of the

German Army, and General Heinz Guclerian (right), commander of the Second Panzer Army.

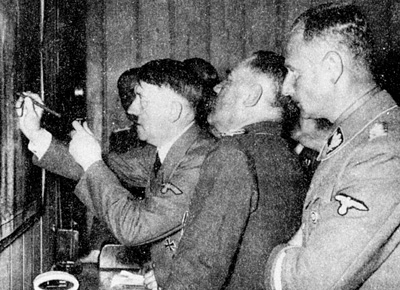

Hitler assumed personal command of the German Army in December 1941 and began interfering in the

direction of combat operations.

Hitler assumed personal command of the German Army in December 1941 and began interfering in the

direction of combat operations.

Back to Table of Contents -- Combat Studies Research # 4

Back to Combat Studies Research List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com