In late July, Army Group Center concluded a successful offensive by closing a large pocket at Smolensk. While this Kessel was being liquidated, the German forces endured the predictable Soviet assaults against their inner and outer encircling rings.

In late July, Army Group Center concluded a successful offensive by closing a large pocket at Smolensk. While this Kessel was being liquidated, the German forces endured the predictable Soviet assaults against their inner and outer encircling rings.

Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, commander of Army Group Center during Barbarossa.

Although hard-pressed at several points, the German lines remained generally intact. [50]

Desperate to spring open the trap around Smolensk, the Soviet High Command

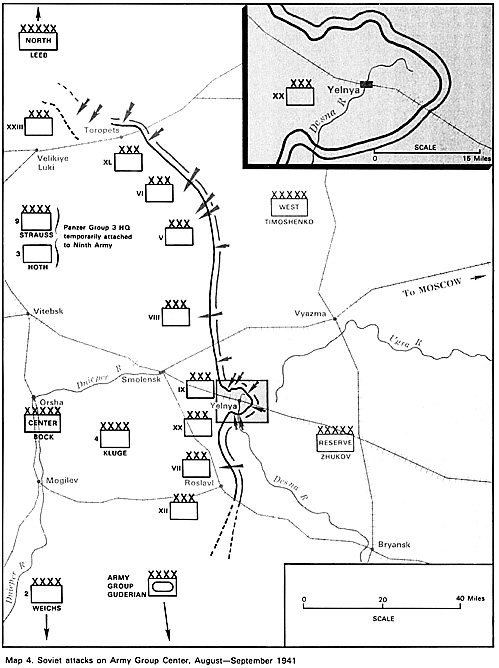

released fresh Red Army forces to reinforce the counterattacks. Particularly ferocious were the relief attacks that Marshal Semen K. Timoshenko's Western Front hurled against the German lines north of Roslavl and near Yelnya. [51]

The Soviet thrust from Roslavl misfired as forces of Panzer Group 2 deftly swallowed the attacking Russians into a new Kessel at the beginning of August. However, the Red Army attacks on the narrow, exposed German salient at Yelnya began a bitter six-week battle for that town.

Seized by the XLVI Panzer Corps of Guderian's panzer group on 20 July, the Yelnya salient enclosed a bridgehead over the Desna River and high ground valuable for the continuation of German offensive operations toward Moscow. If Yelnya had strategic value as a foothold from which future offensive operations might be launched, it also offered tactical liabilities: it was surrounded on three sides by powerful Soviet forces, its rearward communications were clogged with German units fighting to subdue the Smolensk Kessel, and it was also some 275 miles from the nearest German supply dumps. [52]

Since other German forces were initially distracted by the Soviet attack from Roslavl, the motorized units (the 10th Panzer Division and the SS Das Reich Motorized Division) that had captured Yelnya had to hold it until Guderian could bring up marching infantry. As with the containment of surrounded pockets during encirclement battles, this sort of

independent defensive action by panzer and motorized forces had not been envisioned in German prewar manuals on defense.

The two German mobile divisions fought at a severe disadvantage. Both units were fatigued and understrength from their earlier offensive efforts. Ammunition and fuel were in short supply, and the confining terrain within the salient nullified their mobility and shock effect. The 10th Panzer Division suffered from the shortage of infantrymen endemic to such units and therefore was poorly suited for positional defense. [53] To offset these handicaps, Guderian requested that the Luftwaffe concentrate close air support in the Yelnya area. [54]

To Guderian's annoyance, German air support over Yelnya was abruptly withdrawn after only a brief appearance: its operating strength depleted by wear and a shortage of advanced airfields, the Luftwaffe began husbanding its resources for use in operations of "strategic" significance. In preference to the "tactical" defense at Yelnya, the Luftwaffe chose instead to concentrate its planes in the Second Army sector to protect the southern flank of Army Group Center. [55]

Timoshenko continued to concentrate forces opposite Yelnya and began a new series of attacks on 24 July. For two weeks thereafter, Soviet attacks battered the German lines at Yelna virtually without interruption. On 30 July, for example, the German defenders threw back thirteen separate attacks on their positions. [56]

One measure of the growing German peril came on 3 August when Guderian ordered his last available reserve--the guard company for the panzer group headquarters--into the fighting at Yelnya. [57]

In a telephonic report to General Halder on the same date, Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, the commander of Army Group Center, worried aloud about his lack of reserves against the costly Russian attacks. Bock further commented that, with present resources, he could not guarantee against a "catastrophe" at Yelnya. [58]

The catastrophe feared by Bock was averted through the timely arrival of infantry reinforcements, which became available as Russian resistance in the Smolensk Kessel died on 5 August. Guderian quickly moved infantry divisions into the Yelnya salient, hoping that their greater defensive capacities would repel the Russian assaults. Also, flak batteries of the

Luftwaffe's I Antiaircraft Artillery Corps were brought up to bolster the Yelnya defenses. [59]

By 8 August, all Guderian's

mobile units--including those previously holding Yelnya--had been withdrawn from combat and had commenced refitting. [60] This earliest phase of the Yelnya fighting had shown, however, that operational requirements would not allow the Germans the luxury of using their mobile panzer forces only in offensive roles. Moreover, this fighting had again demonstrated the unsuitability of using infantry-poor panzer units in static defensive operations.

As German infantrymen dug in along the Yelnya perimeter, the character of the fighting changed. Hitler, during a conference with Brauchitsch and Bock at Army Group Center headquarters on 4 August, confirmed the necessity of holding Yelnya. [61] Consequently, the German defense at Yelnya was no longer an expedient holding action awaiting offensive thrusts to be renewed. Instead, the newly arrived infantry deployed as best it could into a deliberate defensive posture.

Acknowledging this, Halder noted on 6 August: "At Yelnya, we now have regular position warfare." [62] The Soviets, too, shifted their stance somewhat. With the capitulation of the trapped Red Army forces at Smolensk and Roslavl, a breakthrough by Timoshenko's forces no longer had any major strategic purpose.

Therefore, on 8 August, Soviet attacks temporarily subsided as the Russians awaited the Germans' next move. [63]

When the Russians realized that the Germans were not going to follow their Smolensk triumph with an immediate drive on Moscow, Soviet attacks again flared up along the central front. The German passivity offered the Russians the unique opportunity of battering an entire German army group under conditions of Soviet choosing. Therefore, Marshal Timoshenko's Western Front pressed new attacks between Velikiye Luki and Toropets against the German Ninth Army, which was holding the northernmost portion of Army Group Center's sector. Meanwhile, General Georgi K. Zhukov's newly assembled

Reserve Front was ordered to renew attacks on the inviting Yelnya salient. These assaults began during the second week of August and continued with unprecedented intensity for nearly a month. [64]

Field Marshal von Bock discerned the threat that these attacks posed to Army Group Center. Bock had no desire to see his units ground up piecemeal in battles of attrition and preferred instead to resume the fluid battles of maneuver that had earlier characterized the campaign. When the Soviet attack at Staraya Russa produced the mid-August crisis in the Army Group North area, Bock scorned Hitler's panicky orders to shift mobile forces there from Army Group Center.

On 15 August, Bock argued to Halder that the best course of action against the numerically superior enemy facing his army group was an early return to the offensive. Any transfer of armored striking power away from Bock's command to support the offensives on the German wings would probably destroy the basis for such a general advance by Army Group Center. A prolonged defense, Bock continued, was "impossible in the present position. The front, of Army Group [Center], with its forty divisions sprawled over the 130 kilometer front, is exceedingly overextended, and a changeover to determined defense entails far-reaching planning, to the details of which no prior thought has been given. The

present disposition and line is in no way suited for sustained defense." [65]

In doctrinal terms, Bock recognized that the width of the front held by the army

group precluded the use of the Elastic Defense, since insufficient forces were available to

create defensive depth and reserves ready for counterattack. Also, Army Group Center's frontline trace was defined by its recent offensive advances and therefore was unlikely to provide many terrain advantages for defense. Furthermore, Bock's warning that no logistical provisions had been made for a prolonged defense were shortly affirmed in battle: German forces lacked the stockpiles of supplies and ammunition necessary for sustained positional warfare.

Jumbo Map: Situation Aug 22, 1941: AGN on Defensive

Bock's worst fears came to pass on 21 August when Hitler stripped Army Group Center of most of its mobile divisions in order to support the attacks toward Leningrad and Kiev. While bulletins hailed new German victories on both flanks, Army Group Center manned a thin defensive dike against a tide of Red Army attacks. As Bock had warned, the weak forces and improvised defensive posture of his army group virtually invited disaster.

General Adolf Strauss' Ninth Army manned the northern half of Army Group

Center's stationary front. Marshal Timoshenko's new attacks against Ninth Army benefited not only from heavy artillery and rocket bombardments, but from local Soviet air superiority as well. [66] The German divisions here were overextended and lacked depth: divisional frontages often exceeded twelve miles in width, and the German defenses normally consisted of a string of strongpoints rather than a

continuous defense in depth. [67]

From 11 August onward, Soviet attacks created local crises along the Ninth Army front on an almost daily basis. On Strauss' right, for example, heavy Russian attacks in the VIII Corps sector repeatedly punctured the front of the 161st Infantry Division. On 17 August, this German front was held only by counterattacks by the 161st Division's last few

reserves. Renewed Russian assaults in the same sector broke open the front on succeeding days and captured some of the 161st Division's artillery on 19 August. Its line penetrated again on 21 August, the 161st Division was withdrawn from combat altogether on 24 August. At this time, it was reported to be at only 25 percent strength--a measure of the punishment that the entire VIII Corps had received during this period. [68]

Farther north, tank-supported attacks against the Ninth Army's V and VI Corps also endangered the German front, achieving many small break-ins. Under enormous pressure and in an attempt to tighten its defensive grip, the V Corps withdrew its lines to better defensive terrain on 25 August. [69] Even this

measure proved to be unavailing, for on 28 August, Bock reported to Halder that it was

doubtful whether the V Corps sector could be held for even five more days.

[7]

On 27 August, the Soviets made a deep penetration into the front of the German

26th Division (VI Corps). [71] The German

counterattacks to drive back this threat were so narrowly successful that Bock and Halder

discussed diverting the entire LVII Panzer Corps (which was en route to Army Group North

for the Leningrad operation) to the threatened front of Ninth Army. [72]

While Ninth Army warded off these blows, General Zhukov's Reserve Front was pummeling the German salient at Yelnya. In spite of earlier German attempts to fortify the Yelnya position, that sector of the German front remained short of the Elastic Defense ideal.

As with Ninth Army, first among the German problems at Yelnya was the chronic

shortage of men. Even after infantry divisions relieved the panzer forces in the salient in the

first week of August, the German forces there were not sufficient to organize an elastic

defense in depth. Two General Staff officers, reporting the results of a Yelnya fact-finding

trip to General Halder, flatly described the German units there as "overextended."

[73]

With manpower in such short supply, German defenses in the Yelnya area

generally consisted of a single trenchline instead of the multi-zoned Elastic Defense. No

advanced position or outpost zone stood in front of the main line of resistance, since troops

for these posts could not be spared. Without adequate forward security, many units even

had to abandon the reverse-slope defensive deployment that the Germans preferred for

protection from enemy observation and fire.

An example is that of the 78th Infantry Division. During a forward reconnaissance

on 19 August, while preparing to relieve another division at Yelnya, officers of the 78th

discovered that the German front consisted mostly of a thin line of disconnected rifle pits.

No rearward positions had been prepared, and due to a shortage of mines and barbed wire,

only a handful of obstacles stood in the way of any Soviet attack. The German lines were

poorly sited, being almost entirely exposed to enemy positions on higher ground. As a result,

any daylight movement within the German lines invited a rain of enemy artillery and mortar

shells. In fact, the Soviet fire was so dominant that German casualties had to remain in their

foxholes until after dark before they could be evacuated. [75]

Despite good intentions, leaders of the 78th Division found it virtually impossible to

improve the defensive situation after

occupying their sector on 22 August. A battalion commander in the 238th Infantry

Regiment noted that the strength and accuracy of Soviet fire precluded all efforts to extend

German entrenchments by day, while the necessity of guarding against Soviet infiltration at

night prevented the formation of nocturnal work parties. Also, adequate reserves could not

be found to reinforce threatened sectors; after manning its twelve-mile-wide sector, the

entire 78th Division held less than one full battalion in reserve. [76]

Unable to rely to any great extent on the Elastic Defense principles of depth and

local counterattack, the Germans were also hampered in their attempts to shrivel Russian

attacks with firepower. German small-arms fire was diluted by the wide unit frontages, and

an enduring shortage of artillery ammunition around Yelnya diminished large-caliber fire

support. [77]

With artillery rounds in short supply, the Germans could not afford to conduct

counterbattery fire or even counterpreparations against suspected enemy attack

concentrations. In sharp contrast, the Russians hammered the German lines unrelentingly.

The Soviet bombardments included not only artillery and mortar shells of all calibers, but

also the fearsome new Katyusha rockets and strikes by Russian planes. [78] German prisoners taken by the Soviets at Yelnya

confessed that the heavy shelling-especially in comparison to the miserly German response-

badly hurt German morale. [79] More directly, since

bombardment always plays a major role in positional warfare, the greater weight of Soviet

artillery fire probably caused a proportionately higher German daily casualty rate.

At the beginning of the renewed Yelnya battles, the German defense conformed to established doctrine in one important respect: panzer units were held in reserve to the rear of the German front. Although theoretically available for counterattack, these forces--the XLVI Panzer Corps, which had been relieved earlier on the Yelnya perimeter--with one exception did not intervene in the fighting. Through late August, the XLVI Panzer Corps

(the Grossdeutschland Motorized Infantry Regiment, 10th Panzer Division, and SS Das Reich Motorized Division) was belatedly refitting and therefore was exempt from counterattack use. Even before these units had completed refitting, Guderian was badgering Bock to release them to reinforce the offensive drive on Kiev.

After a series of heated arguments between Guderian and his superiors,

Grossdeutschland and Das Reich were finally ordered south.

[80]

By that time, however, Bock judged that Fourth Army's deteriorating defensive front could only be salvaged by a major panzer counterattack and therefore detached the 10th Panzer Division from the XLVI Panzer Corps and assigned it to the Fourth Army. Thus it was that the 10th Panzer Division was the only one of the available mobile reserves that finally plunged into the fighting on 30 August. [81]

In its general outline, Fourth Army's battles for the Yelnya salient followed the same sequence as the fighting in the Ninth Army area. Prodigious Soviet bombardments and local attacks eroded the defending German divisions, and as German reserves were exhausted, the Russians exploited minor break-ins to pry open the German defensive front.

[82] A major break occurred on 30 August when the Soviets drove a ten-kilometer wedge into the Fourth Army's 23d Infantry Division. (It was this serious penetration, which carried to a depth on line with the VII Corps headquarters, that prompted the commitment of the 10th Panzer Division. [83]

Although the panzer counterattack temporarily stabilized the situation, Brauchitsch, Bock, and Halder agreed on 2 September that Yelnya was no longer tenable in view of the strained condition of the Fourth Army. Consequently, on 5 September, German troops abandoned the Yelnya salient in a planned withdrawal. [84]

Russian attacks against Ninth Army broke off on 10 September, and the assaults against the Fourth Army ceased six days later. In both areas, the Soviets could point to limited territorial gains as the fruits of their efforts. [85]

Indeed, the operational withdrawal from Yelnya was the first imposed on the German Army in World War II. However, the full significance of Army Group Center's defensive battles during August and early September could not be measured solely in real estate lost or won.

Like a great winded beast, Army Group Center had stood stolidly in place for more than six full weeks while the Russians stormed against its front. The Russians had been able to choose the times and places of attack and had possessed advantages in quantities of men and materiel. The Germans had waged an improvised defense on unfavorable ground, and because of the extended unit frontages and inadequate combat resources, a doctrinal Elastic Defense relying on depth, local maneuver, firepower, and counterattack had been impossible.

As a result of these conditions, Army Group Center paid an extraordinarily high price in blood. Whereas the Elastic Defense had been designed to minimize personnel losses in positional warfare even in the face of enemy superiority, the improvised methods that the German units were compelled to use in the central front battles resulted in heavy casualties. In the Ninth Army sector, the entire 161st Division had been temporarily disabled, while all of the divisions in the V and VIII Corps had their combat strength seriously diminished. For the Fourth Army, the hardest fighting had occurred in the Yelnya salient, where nine German divisions had seen combat since the end of July. In these divisions, infantry losses had been particularly high.

The 263d Infantry Division, for example, had taken 1,200 casualties in only seven days of combat at Yelnya. The 78th Infantry Division reported the loss of 1,155 officers and men in just over two weeks, while the 137th Infantry Division lost nearly 2,000 in the same amount of time. [86] These losses probably represented 20 to 30 percent of the total infantry strength of these divisions at the time the defensive battles began.

These personnel losses permanently diminished the combat power of Army Group Center, and as General Halder had foreseen earlier, German personnel replacements were running out. The chief of the General Staff noted on 26 September that convalescents returning to duty constituted the only remaining short-term source of replacement manpower. [87]

Although a few replacements trickled down to Bock's tired divisions during

September, Army Group Center still reported a net shortage of 80,000 men on 1 October.

Since most of these unreplaced losses were infantrymen, the German ability to seize and

hold terrain was seriously eroded. [88]

Furthermore, growing shortages of frontline officers and noncommissioned officers also affected the combat worthiness of German units. For example, the war diarist for Army Group Center noted that, two and one-half months after its near destruction by Timoshenko's forces in August, the luckless 161st Division continued to suffer needless casualties due to the division's lack of experienced junior leaders. [89]

The continuous defensive fighting also prevented Army Group Center from

building up any appreciable stocks of ammunition. In fending off the attacks on the Ninth and Fourth Armies, the Germans had consumed ammunition almost as quickly as the overtaxed supply columns could deliver it. This meant that Army Group Center would either have to await the stocking of forward supply dumps before it resumed the offensive or continue to operate on an ever-lengthening logistical thread. As events turned out, Army

Group Center eventually did a little of both. [9]

Army Group Center's positional battles left other less-visible scars. Timoshenko's attacks on Ninth Army disrupted the timetable for shifting mobile units northward to support Leeb's attack on Leningrad. A degree of command antagonism also developed between Bock and Leeb as the two field marshals, their nerves fraying, haggled over the availability of these forces.

Also, the command relationship between Field Marshal von Bock and General Guderian was permanently soured by arguments over the control and use of mobile reserves in the Yelnya area. This growing friction between senior commanders would scarcely have mattered had it not been for the decline in health and influence of Field Marshal von Brauchitsch, the German Army's commander in chief. (Brauchitsch finally suffered a heart attack on 10 November.) Without Brauchitsch's firm and steady hand to adjudicate disputes, coordination between German armies increasingly fell to the dilettantish Hitler. Consequently, the strenuous defensive battles of August and September helped bring these problems to a boil.

When the German Fourth Army took control of the Yelnya sector from Guderian's

headquarters on 22 August, conditions there appalled General Gunther Blumentritt, Fourth

Army's chief of staff. As he later wrote: "When I say that our lines are thin, this is an

understatement. Divisions were assigned sectors almost twenty miles wide. Furthermore, in

view of the heavy casualties already suffered in the course of the campaign, these divisions

were usually understrength and tactical reserves were nonexistent."

[74]

When the German Fourth Army took control of the Yelnya sector from Guderian's

headquarters on 22 August, conditions there appalled General Gunther Blumentritt, Fourth

Army's chief of staff. As he later wrote: "When I say that our lines are thin, this is an

understatement. Divisions were assigned sectors almost twenty miles wide. Furthermore, in

view of the heavy casualties already suffered in the course of the campaign, these divisions

were usually understrength and tactical reserves were nonexistent."

[74]

German troops defend captured Russian village, summer 1941.

German troops defend captured Russian village, summer 1941.

Back to Table of Contents -- Combat Studies Research # 3

Back to Combat Studies Research List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com