The greatest land campaign of World War II began on 22 June 1941 when Adolf Hitler ordered German armies eastward against the Soviet Union.

The greatest land campaign of World War II began on 22 June 1941 when Adolf Hitler ordered German armies eastward against the Soviet Union.

German infantrymen march forward along a dusty Russian road, July 1941

Confident that Operation Barbarossa would result in a rapid offensive victory over the Russians, the Germans were unprepared for the prolonged, savage conflict that followed. Germany's unpreparedness showed in a variety of ways. Strategic planning was haphazard, logistical support was insufficient, and given the magnitude of both the theater and the enemy, the number of committed German divisions was wholly inadequate.

Jumbo Map: Operation Barbarossa: June 22-August 25 1941

The first year of the Russo-German War consisted of two separate phases. The first phase-the German initiative-lasted from 22 June until the first week of December 1941. During that period, three German army groups, numbering more than 3 million men, marched toward Leningrad, Moscow, and Rostov.

The second phase--the Soviet initiative--began at the end of 1941, as the final German attacks ground to a halt short of Moscow. From early December until the following spring, the Soviets lashed back at the Germans with a series of furious counteroffensives.

German defensive operations played a major role in each phase. The accounts of the spectacular early successes of Barbarossa tend to obscure the fact that those offensive victories frequently required hard defensive fighting by German units. Once the Soviet winter counteroffensives began, German military operations were, of course, almost entirely defensive.

In both phases, the German Army was largely unable to execute the defensive techniques prescribed by German doctrine. As the German armies advanced from June to December 1941, the deployment posture of German divisions was governed by offensive rather than defensive considerations. Consequently, German units seldom had the time or the inclination to organize the sort of careful defense in depth described in their training manuals. Likewise, German defensive operations during the Soviet winter counteroffensives seldom conformed to the procedures in Truppenfuhrung. Limitations imposed by terrain and weather; critical frontline shortages of men, supplies, and equipment; and Hitler's reluctance to allow any withdrawals by forward elements prevented a general implementation of the Elastic Defense. Instead, embattled German divisions resorted to expedient defensive methods dictated by the exceptional conditions in which they found themselves.

The Defensive Aspects of Blitzkrieg

To avoid the dissipation of a two-front war, the German High Command expected to "crush Soviet Russia in a lightning campaign" during the summer of 1941 (see map 1). The key to this rapid victory lay in destroying "the bulk of the Russian Army stationed in Western Russia ... by daring operations led by deeply penetrating armored spearheads." To achieve this goal, the Germans planned to trap the Soviet armies in a series of encircled

"pockets." [1]

Jumbo Figure 5. German Keil und Kessel tactics, 1941

Not only would this strategy chop the numerically superior Soviet forces into manageable morsels, but it also would prevent the Soviets from prolonging hostilities by executing a strategic withdrawal into the vast Russian interior.

In the campaign's opening battles, the Germans used Keil und Kessel (wedge and caldron) tactics to effect the encirclement and destruction of the Red Army in western Russia (see figure 5). After penetrating Soviet defenses, rapidly advancing German forces--their Keil spearheads formed by four independent panzer groups--would enclose the enemy within two concentric rings. The first ring would be closed by the leading panzer forces and would isolate the enemy. Following closely on the heels of the motorized elements, hard-marching infantry divisions would form a second inner ring around the trapped Soviet units. Facing inward, these German infantry forces would seal in the struggling Russians, containing any attempted breakouts until the caldron, or pocket, could be liquidated.

Meanwhile, the mobile forces in the wider ring faced outward, simultaneously parrying any enemy relief attacks while preparing for a new offensive lunge once the pocket's annihilation was complete. [2]

Generally, in offensive maneuvers, the Germans sought to place their units in a position from which they could conduct tactical defensive operations. [3] This way, the Germans could enjoy both the advantages

of strategic or operational initiative And the benefits of tactical defense. True to this principle, the encirclement operations conducted during Barbarossa contained major defensive components. Once a Kessel was formed, the temporary mission of both the panzer and the infantry rings was defensive: the inner (infantry) ring blocked enemy escape, while the outer (armored) one barred enemy rescue. The defensive fighting that attended the formation and liquidation of these pockets revealed serious problems in applying German defensive doctrine, however.

Fearsome in the attack, German panzer divisions were ill-suited for static defensive missions due to their relative lack of infantry. [4]

Prewar German defensive doctrine had envisioned using infantry for defensive combat and reserving panzer units for counterattacks, a role commensurate with their supposedly offensive nature. Panzer divisions were neither trained nor organized to fight defensively without infantry support. However, during the deep, rapid advances of Barbarossa, the German panzers routinely ranged far ahead of the marching infantry and were therefore on their own in defensive fighting.

During their deep encirclements, panzer divisions found even their own self-defense to be a problem. Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, when describing his experiences as a panzer corps commander in Russia during the

summer of 1941, observed that "the security of a tank formation operating in the enemy's rear largely [depended] on its ability to keep moving. Once it [came] to a halt, it [would] be immediately assailed from all sides by the enemy's reserves." The position of such a stationary panzer unit, Manstein added, could best be described as "hazardous."

[5]

To defend itself, a halted panzer unit would curl up into a defensive laager called a hedgehog. These hedgehogs provided all-around security for the stationary panzers and were used for night defensive positions as well as for resupply halts. [6]

The panzer hedgehogs solved the problem of self-defense but were not suitable for controlling wide stretches of territory. The German Keil und

Kessel offensive tactics, however, required that enveloping panzer divisions control terrain from a defensive posture: first, until the following infantry could throw a tighter noose around the encircled enemy and then as a barrier against relief attacks by enemy reserves.

Not surprisingly, the panzer divisions often had difficulty in performing these two tasks.

On at least one occasion, for example, an encircling German panzer unit actually had to defend itself from simultaneous attacks on both its inner and outer fronts. The 7th Panzer Division, having just closed the initial ring around the Smolensk pocket, faced such a crisis on 1 August 1941. General Franz Halder, the chief of staff of the Army High Command, glumly wrote in his personal diary that "we need hardly be surprised if 7th Panzer Division eventually gets badly hurt." [7] Ideally, German motorized infantry divisions should have assisted the panzers in defensive situations. However, in 1941, the number of motorized divisions was too few and the scope of operations too great for this to occur in practice. [8]

Until relieved by infantry, German panzer divisions were hard-pressed to contain encircled enemy forces. As Red Army units tried to escape from a pocket, the German panzers continually had to adjust their lines to maintain concentric pressure on the Soviet

rear guards and to block major breakout efforts. Containment of such a "wandering pocket"

required nearly constant movement by the panzer divisions, a process that prevented even

the divisional infantry units from forming more than hasty defensive positions.

[9]

Even so, until the following infantry divisions closed up, the panzer ring around a Kessel remained extremely porous. [10] As a result, many Soviet troops avoided German prisoner-of-war cages by simply filtering through the

hedgehog picket line. Although the panzer divisions did their best to disrupt this egress with artillery fire and occasional tank forays, German commanders conceded that large numbers of Russians managed to melt through the German lines. [11]

Soviet relief attacks posed problems of a different sort for the German panzer units. While the Germans devoted themselves to forming and digesting a particular Kessel, Soviet units outside the pocket often had time to gather their operational wits and organize a

coordinated counterblow. When delivered, these counterattacks fell heavily on the outer ring of the German armor. The panzer units fared better in these circumstances, since they

could often use their own mobility and shock effect to strike at the approaching Soviets. However, the German defensive problem was greatly compounded when the Soviet counterattacks included T-34 or KV model tanks, both of which were virtually invulnerable

to fire from German tanks. [12]

The predicament of the German armor in these circumstances might have been truly desperate had it not been for the support that attached Luftwaffe antiaircraft batteries provided to most of the panzer divisions. Originally assigned to the spearhead divisions to protect them against Soviet air attack, these Luftwaffe batteries--and especially the 88-mm high-velocity flak guns--had their primary mission gradually altered from air defense to ground support. [13]

Although German armored units were thus generally successful in repelling counterattacks, the sheer weight of these coordinated relief attempts--especially when supported by the heavier Soviet tanks--hammered the panzer divisions as no other fighting in the war had yet done.

The German infantry divisions, tramping forward in the wake of the motorized vanguards, had the double responsibility of providing timely support for the armored spearheads and of concurrently guarding the flanks of the German advance against Soviet counterattacks. General Halder described the marching infantry as a "conveyor belt" defensive screen along which successive units passed en route to the Kessel battles at the front.

[14] The German infantry advanced at a

forced-march pace in order to catch up with the mobile forces as quickly as possible. (Those infantry divisions marching immediately to the rear of the panzer groups were especially abused by being shunted onto secondary roads in order to avoid congesting the supply arteries of the far-ranging panzers. [15]

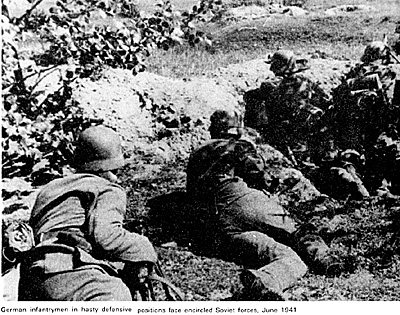

Like the panzer forces, the German infantry units had defensive difficulties of their own. The lathered haste of the infantry advance reduced defensive efficiency, since there was little time for organizing defensive positions. In accordance with published German doctrine, infantry units tried to site their emplacements on the reverse slopes of hills and ridges and stood poised to eject penetrating enemy forces with immediate

counterattacks. [16]

As a rule, however, only hasty defensive positions could be prepared during halts, and even then, infantry units remained deployed more in a marching posture than in the alignments specified by the Elastic Defense. [17]

Even though the infantry advance was rapid, infantry units did not receive the same kind of protection from Soviet counterattacks that mobility provided for motorized units. From the beginning of the campaign, Soviet counterblows were almost a daily occurrence for German infantry units. An early Soviet High Command directive ordered Red Army counterattacks at every opportunity. This directive continued to animate Soviet tactics throughout the summer and autumn of 1941.

[18]

To supply additional protective fire for German infantry units on the march, artillery batteries of various calibers were spaced throughout the march columns. By providing responsive fire support to nearby units, these batteries simplified the otherwise complex problem of fire control for scattered, moving, and occasionally intermixed infantry forces. [19]

In some units, improvised flak combat squads, consisting of two 88-mm and three 20-mm antiaircraft guns, were also distributed among the ground infantry forces to bolster defensive firepower. [20]

Moreover, the dispersal of artillery and antiaircraft units throughout the divisional columns reduced the vulnerability of the guns to ground attack-an important consideration in the chaos of June and July 1941 when bypassed or overlooked Red Army units often

appeared unexpectedly along the march route.

The posting of artillery and flak units in the infantry march columns also lent additional antitank firepower to the foot soldiers. As with the panzers elsewhere, the infantry found its Pak antitank guns and antitank rifles ineffective against any but the lightest Soviet tanks. The result, as one German commander wrote, was that "the defense against enemy tanks had to be left to the few available 88mm Flaks, the 105mm medium guns, and the division artillery." [21]

Although the use of artillery in a direct-fire, antitank role was consistent with German doctrine in Truppenfuhrung-and was, for that matter, in keeping with the German practices of 1917 and 1918--the antitank experience was unpleasant for German gunners. The German artillery pieces and their caissons were cumbersome, had high silhouettes, and were too valuable to be risked in routine duels with Soviet tanks.

[22]

A German newspaper sketch showing German troops destroying a Soviet tank with grenades and gasoline.

Such heroism exacted a high price, and heavy infantry casualties often resulted when Soviet tanks actually overran German positions. On 10 July, for example, the German Eleventh Army reported that elements of its 198th Infantry Division had been caught without antitank support and mauled badly by a heavy tank attack.

[24]

Not surprisingly, such incidents caused some German infantry units to be skittish in the face of tank assaults. Experience proved to be the best tonic for this condition: German division commanders reported that any lingering tank fear disappeared following the first successful defeat of a

Russian tank onslaught. [25]

One of the first set-piece antitank actions fought by German infantry in World War II occurred on 25-26 June near Magierov. There, the German 97th Light Infantry Division hastily deployed its own infantry and artillery forces in depth to defeat a division-strength Soviet tank attack. In this engagement, the Russian tank and infantry contingents were separated and then annihilated in a textbook application of the German antitank

technique. [26]

During the first months of Barbarossa, German infantry waged some of its

heaviest defensive combat while containing encircled Soviet units. Keil und Kessel tactics required that the German infantry divisions reduce pocketed Russian forces by offensive pressure and also block the frenzied Russian attempts to break out.

One of the campaign's first defensive engagements to be widely reported by the German press illustrated the tactical difficulty of these battles. While barring the eastward escape of Red Army units from the Bialystok Kessel during the night of 29-30 June, the 82d Infantry Regiment (31st Infantry Division) was subjected to successive attacks by Russian infantry, cavalry, and tank forces.

This German regiment had been unable to establish a defense in depth or even a continuous defensive line due to the extreme width--more than ten kilometers--of the regimental sector. Furious Soviet assaults conducted throughout the night penetrated the German line at several points, and some German units found themselves attacked simultaneously from front, flanks, and rear.

In fact, the situation became so critical that regimental headquarters staff and communications personnel had to fight as infantry to prevent the German lines from being completely overrun. Although the Germans managed to prevent a large-scale rupture of their defensive front, they could not block the escape of small bands of Soviet troops who, abandoning their heavier weapons and equipment, stole through the German lines during the chaos of combat. [27]

Luckily for the Germans, Russian counterattacks during the early weeks of Barbarossa were frequently uncoordinated and lacked tactical sophistication. The surprise German onslaught had caught the Red Army in a state of disarray, and the speed and depth of the German advance prevented the Russians from regaining their operational equilibrium. [28]

As a result, Soviet counterattacks often lurched forward in piecemeal fashion, with little effective cooperation between supporting arms or adjacent units. Units attacking in the first week of July against

the infantry-held flanks of German Army Group South, for example, used tactics that were "singularly poor. Riflemen in trucks abreast with tanks [drove] against our firing line, and the inevitable result [was] very heavy losses to the enemy." [29]

One German general, in reporting his frontline observations to General Halder, described the Russian attack method as "a three minute artillery barrage, then pause, then infantry attacking as much as twelve ranks deep, without heavy weapon support. The [Russian] men [started] hurrahing from far off. [There were] incredibly high Russian

losses." [30]

By the end of July, the German Army had triumphantly concluded the

encirclement battles designed to destroy Soviet forces in western Russia. While shredding the Soviets with blitzkrieg offensive operations, German units had fought a large number of tactical defensive engagements. The German forces had generally been successful in these actions, although combat conditions had rarely allowed them the full use of standard German doctrine.

Instead of being decisively smashed, however, Soviet military resistance continued unabated. Despite the destruction of several Russian armies in encirclements at Bialystok, Minsk, and Smolensk, as well as in lesser pockets elsewhere, Halder conceded that "the whole situation makes it increasingly plain that we have underestimated the Russian Colossus.... At the outset of the war we reckoned with about 200 enemy divisions. Now we

have already counted 360. These divisions indeed are not armed and equipped according to our standards, and their tactical leadership is often poor. But there they are, and if we smash a dozen of them, the Russians simply put up another dozen." [31]

As the entire German strategy for Barbarossa had gambled on shattering Soviet resistance in a few battles of encirclement, continued Soviet pugnacity confounded German planning and provoked a strategic reassessment by the German High Command. This strategic reassessment shaped the next series of defensive battles fought by German soldiers in Russia.

Given the anemic firepower of the German Paks and the reluctance of the artillerists, the German infantryman often became the antitank weapon of last resort. German combat reports frequently spoke of Soviet tanks being knocked out in close combat by German infantrymen using mines and grenade clusters. [23]

Given the anemic firepower of the German Paks and the reluctance of the artillerists, the German infantryman often became the antitank weapon of last resort. German combat reports frequently spoke of Soviet tanks being knocked out in close combat by German infantrymen using mines and grenade clusters. [23]

German infantrymen in hasty defensive positions face encircled Soviet forces, June 1941.

German infantrymen in hasty defensive positions face encircled Soviet forces, June 1941.

Back to Table of Contents -- Combat Studies Research # 3

Back to Combat Studies Research List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com