In the years following 1918, all major armies sought to divine from the Great War's confusing impressions the nature of future wars. Would future battlefields resemble the entrenched Stellungskrieg of the 1914-17 Western Front? Or would new tactics, together with the new technology of armored vehicles and motorized movement, produce fluid battles of maneuver? The development of the German blitzkrieg offensive techniques foresaw the latter scenario, a leap of faith not shared by the French or the British.

In the years following 1918, all major armies sought to divine from the Great War's confusing impressions the nature of future wars. Would future battlefields resemble the entrenched Stellungskrieg of the 1914-17 Western Front? Or would new tactics, together with the new technology of armored vehicles and motorized movement, produce fluid battles of maneuver? The development of the German blitzkrieg offensive techniques foresaw the latter scenario, a leap of faith not shared by the French or the British.

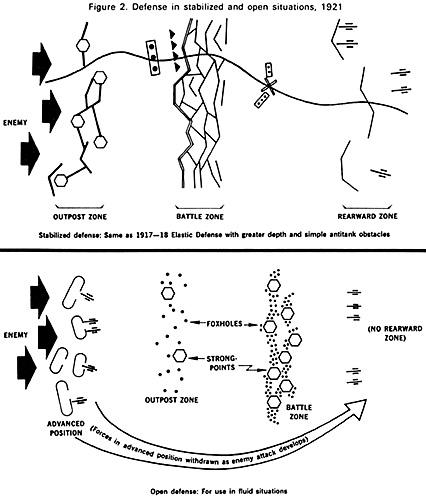

Figure 2. Defense in stabilized and open situations, 1921

The clarity of German doctrinal vision in defensive matters was less certain, however. By their very nature, defensive operations generally imply surrendering the initiative to the enemy. As a consequence, defensive measures must be able to accommodate the attacker's tactic of choice, a circumstance that breeds caution and redundancy. For the purposes of defining defensive doctrine, the Germans were unable to predict for certain whether future wars would be of a positional or of a maneuver nature. Therefore, the German Army pursued a doctrinal compromise that would operate effectively in either environment.

The Elastic Defense became the German Army's all-purpose defensive doctrine. As the familiar, proven method of World War I, the Elastic Defense was the obvious theoretical starting point for interwar doctrinal development. With minor alterations, it remained the essence of German defensive practice until the beginning of World War II. However, the retention of the basic Elastic Defense concept was not a simple, straightforward process.

To many German officers, the Elastic Defense seemed too trench oriented, and they argued that the retention of a doctrine designed for positional warfare would invite disaster in future wars. At the very least, the Elastic Defense needed to have its antitank properties upgraded in order to confirm its continuing validity in an armored warfare environment. Therefore, these and other considerations weighed on the interwar development of German defensive doctrine.

The building of a new German Army began in 1919. Since wholesale desertions had caused the old Imperial German Army to evaporate within weeks of the 1918 armistice, the new Reichswehr* was created virtually from scratch. [24]

(*Technically, the new German Army was the Reichsheer. However, except in offical documents, the term Reichswehr was used indiscriminately to describe both the German armed forces in general and the

land army in particular. The Reichswehr went through a series of provisional incarnations immediately after the war before assuming its "final" form in 1920.)

Among the many immediate problems pressing the Reichswehr and its acting chief of staff, General Hans von Seeckt, was the publication of new field manuals to guide postwar training.

Seeckt sought to compile the most practical and effective combat procedures from the Great War into a single doctrinal manual. First published in 1921, Fuhrung und Gefecht der uerbundenen Waffen (Leadership and Combat of the Combined Arms) remained the standard operations manual for the Reichswehr until 1933.

The German postwar uncertainty about the positional versus the maneuver visions of future war was evident in the new manual. Although Seeckt was an ardent advocate of maneuver warfare, his early influence was counterbalanced by other senior officers of the "trench school." [25]

To these, the harsh catechism of Stellungskrieg demanded the retention of a trench-oriented defense doctrine. Fuhrung und Gefecht compromised by conceding that either form of warfare was possible and showed how the Elastic Defense could be adapted to either circumstance (see figure 2).

For stabilized situations, Fuhrung und Gefecht prescribed an elastic defense in depth that was identical in every major detail to the Elastic Defense described in the 1917 and 1918 Imperial German Army pamphlets. The defense was to be organized in three principal defensive zones as before, within which the defending forces would "exhaust [the enemy's] power of attack by resistance in depth." [26]

Attacking enemy forces were to be subjected to a withering combination of small-arms and artillery fire throughout the depth of the battle area. Defending units would "seek timely and unnoticed evasion of hostile superiority at one point, while offering resistance

elsewhere (mobile defense)."

[27]

Finally, fierce counterattacks by engaged units as well as by reserve forces held in

readiness to the rear would be "of decisive importance." [28]

Fuhrung und Gefecht thus endorsed the same defensive formula of

depth, firepower, maneuver, and counterattack as had been developed during World War I. The only departures from World War I usage were minor. Defensive zones were increased in depth, and the distance between them was extended to ensure that, "in the event of a breakthrough, a displacement by the enemy artillery [would] be necessary before the attack [could] be continued against the next position." [29]

Furthermore, the 1921 manual finally deigned to discuss measures for defense against tanks, although the measures consisted mainly of local obstacles and artillery concentrations along tank avenues of approach.

[30]

When forces were defending in open situations during battles of maneuver, Fuhrung und Gefecht simply advised a somewhat looser application of the Elastic Defense. Since the presumed pace of operations would prevent the construction of fully fortified trenchworks, both the outpost zone and the battle zone would normally consist of a system of "foxholes and weapons pits" with out connecting trenches. [31]

A rearward zone would not even be constructed. To provide greater operational depth and warning, an advanced position would be created where possible. This position would be held by covering forces whose missions were to provide early warning of the enemy's approach, confuse the enemy as to the location of the actual defensive zones, and in general, constitute an additional defensive buffer when the armies were not in close contact. [32]

Despite these slight alterations to the defensive posture, the "defense in open situations"

still conformed to the Elastic Defense. Depth and maneuver were emphasized in order to strengthen the combat power of the defending forces, and integrated firepower and counterattack would still be used to destroy the enemy. [33]

The Reichswehr's principal doctrinal publication thus steered an equivocal course between the positional and the maneuver scenarios, prescribing a form of Elastic Defense for each. However, in practice, the willful General von Seeckt temporarily suspended the

Elastic Defense instructions in Fuhrung und Gefecht.

Seeckt, whose wartime experience had been mostly on the more fluid Russian and Balkan Fronts, retained an enthusiasm for maneuver undampened by the gory disappointments of France and Flanders. Seeckt was convinced that a renewed emphasis on bold offensive maneuver could, in the future,

result in rapid battlefield victories. A man of strong convictions, Seeckt was intolerant of subordinates who did not endorse his ideas. Those officers of the trench school who were unwilling to adapt themselves to Seeckt's theories were either silenced or dismissed.

[34]

Therefore, Seeckt was able to bend the Reichswehr's training sharply in the direction of mobility and maneuver. Although the Elastic Defense remained on the books as official Reichswehr doctrine, Seeckt whipped the German Army into a fervid pursuit of mobility and offensive action that caused the Elastic Defense to be all but ignored in practice.

Seeckt wrote in a 1921 training directive that the strongest defense lay in mobile attack, a policy that cultivated offensive action at the tactical level for even defensive purposes. [35]

Seeckt insisted that skillful maneuver could reduce virtually all battlefield actions to a form of meeting engagement in which aggressive actions would prevail. [36] Where overwhelming enemy strength precluded the

possibility of attack, Seeckt advocated a mobile delaying action to preserve freedom of maneuver by friendly forces. [37]The use of initiative

and speed of movement to create opportunities for offensive thrusts was emphasized in Reichswehr field exercises. Also, as early as 1921, military maneuvers examined the feasibility of using motor vehicles to enhance mobility and offensive striking power in nominally "defensive" scenarios. [38]

Seeckt's emphasis on swift offensive action suited the temper and means of the German Army. German military studies conducted after World War I were virtually unanimous in blaming Germany's defeat on the exhausting Stellungskrieg. [39]

Thus, Seeckt's theories pointed a way out of that attritional wilderness. By means of rapid offensive blows against even superior rivals, Germany hoped to avoid the attritional quicksand of the Great War and return instead to the battles of maneuver and annihilation

at which German armies had traditionally excelled.

Too, the pitifully small resources allowed the Reichswehr by the Treaty of Versailles precluded positional defense. Restricted to an army of only 100,000 men, the Germans were prohibited from possessing antitank or antiaircraft guns and from erecting defensive fortifications along their western frontiers. [40]

These stipulations meant that, for the foreseeable future, the Reichswehr would be only the shadow of an army, patently incapable of serious defensive operations save those related to internal security. The Reichswehr's defensive impotence was revealed in 1920 and 1921 when incursions by Polish and Soviet irregulars along Germany's eastern borders had to be opposed by hastily assembled Freikorps units rather than by the inconsequential Reichswehr. [41]

When French forces occupied the Ruhr in 1923, German studies assessing the possibility of resistance by the Reichswehr concluded that any such action was militarily impossible. [42]

Theory and reality thus converged to enforce a reliance on maneuver and offensive initiative within the new German Army since no other type of defensive action seemed desirable or practicable. Remembering the attritional slaughter of the Great War, many German officers were eager to embrace any tactical system that promised to avoid such battles. Too, the Versailles constraints guaranteed that the Reichswehr could not resort to

the Elastic Defense that had stymied the Allies in 1917 since the Reichswehr was forbidden to have the materiel to do so.

German offensive and defensive tactics were based on Seeckt's theories of maneuver and aggressive action and were in effect until the early 1930s. Then, German offensive and defensive doctrines diverged: offensive practice continued on the road to mobility that led finally to blitzkrieg, while defensive doctrine reverted to more conservative practices reminiscent of the Great War. Accordingly, the Elastic Defense was revived for three major reasons.

Second, the German Army began quietly to ignore some of the more onerous

provisions of the Versailles Treaty, thereby increasing German military strength. This therefore allowed German military leaders to consider a wider variety of strategic options than the desperate, all-purpose formula of offensive maneuver championed by Seeckt. [43]

Finally, a rapprochement between the French and German governments in the late 1920s lessened French hostility and, with it, the likelihood of renewed French military intervention. The looming threat of the French Army-its potential for strategic mischief painfully demonstrated by the 1923 occupation of the Ruhr-was greatly diminished by the emerging French reliance on the Maginot Line. With French military resources so strongly committed to the passive Maginot doctrine of couverture from 1930 onward, Germany's overall military security was better than it had been at any time since 1918.

[44]

In this atmosphere of greater strength and security, the Reichswehr took a more well-rounded view of military strategy. The Seecktian emphasis on aggressive maneuver was relaxed, and the German Army once again acknowledged that traditional defensive operations -- including, in certain circumstances, positional warfare -- would probably be necessary in future conflicts. Consequently, the Elastic Defense was revived as the

fundamental German defensive technique.

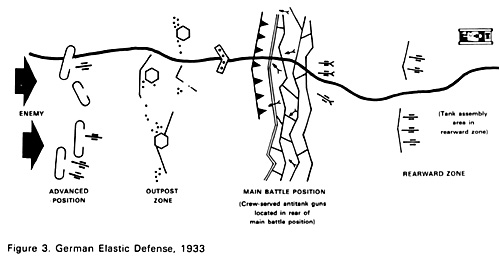

The German field manuals published in the 1930s revealed the renaissance of the Elastic Defense and, with a few changes in later editions, were still in effect at the beginning of World War II. The most important of these publications, entitled Truppenfuhrung (Troop Command), appeared in 1933 and replaced Fuhrung und Gefecht as the basic German operations manual. Prepared under the supervision of General Ludwig Beck, chief of the German General Staff from 1933 to 1938, Truppenfuhrung endorsed the

traditional German method of elastic defense in depth.

[45]

In fact, the doctrine in Truppenfuhrung ended the distinction between positional

defense and maneuver defense that had been created in Fuhrung und Gefecht and

specifically declared that "the defense of a hastily prepared, unreinforced position [such as would occur in open warfare] and that of a fully completed position is conducted on the same principles." [46]

Also, the advanced position that Fuhrung und Gefecht had placed in front of the defensive zones in open situations was made standard. Consequently, the 1933 version of the Elastic Defense consisted of the same three defensive zones as had appeared in Ludendorff's original concept, but with an additional advanced position posted in front (see figure 3). [47]

In addition to Truppenfuhrung, other specialized manuals such as the 1938 Der Stellungskrieg and the 1940 Die Stundige Front elaborated on the problems of positional warfare in greater tactical detail. [48]

These manuals were supplemented by instructional material in professional journals. For example, from 1936 onward, Militar-Wochenblatt periodically published tactical problems hypothesizing static defensive operations. Significantly, the solutions to these exercises discussed the experiences of 1917 and 1918 as illustrative examples of proper technique. [49]

Together, these field manuals and journal articles breathed new life into the Elastic Defense doctrine and fully revived the defensive system that the German Army had developed during World War I.

Other German military authors addressed the strategic ramifications of the Elastic Defense, assuring their readers that this new interest in defensive tactics did not signal a full return to the disastrous strategy of attrition. General Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb (later to command Army Group North during Operation Barbarossa in 1941) wrote a series of historical articles on defensive operations in Militarwissenschaftliche Rundschau in 1936 and 1937. Although predicting that future wars would still be decided by offensive maneuver, he argued that strategic defensive operations could not be discounted: "We Germans have to look to defensive operations as an important, essential method of conduct of war and conduct of combat, since we are in a central position, surrounded by highly equipped nations. Defensive should not be kept in the background as before the last war."

[50]

Leeb further stressed that the tried defensive principles of the Great War-depth

and counterattack-could still be effective in modern battles of maneuver. [51] Echoing Leeb, a Major General Klingbeil warned

readers of Militar-Wochenblatt in 1938 not to discredit positional defensive operations on

principle since they could create circumstances favorable for decisive offensive action.

[52]

The new manuals and spate of journal articles demonstrated the remarkable extent to which German military thinkers had reaccommodated themselves to the possibility of positional warfare. While most professed a preference for offensive maneuver, German theorists conceded that Stellungskrieg was likely to be present, at least to a limited extent, on future battlefields. [53]

Within this intellectual climate, Beck's revival of the orthodox doctrine of the Elastic Defense seemed not only prudent, but even virtually indispensable.

The problem of armored warfare, however, prevented a simple return to Great War tactics. World War I had provided brief glimpses of the potential combat value of tanks and motor vehicles, and from 1919 to 1939, all armies puzzled over how best to exploit these new machines.

In terms of German defensive doctrine, the tank problem posed two distinct questions. First, how could German defenses be made attack-proof against enemy tank and tank-infantry forces? Second, what was the best defensive use of the new German panzer units? The Germans framed their answers to both of these questions within the Elastic Defense schema.

Senior German officers observe Reichswehr maneuvers, circa 1928

Senior German officers observe Reichswehr maneuvers, circa 1928

First, a gradual broadening of German military perspective began following General Seeckt's 1926 resignation. Although Seeckt's ideas -- and Seeckt himself -- continued to be influential for some time, his successors were more tolerant of traditional doctrinal theories.

Figure 3. German Elastic Defense, 1933

Figure 3. German Elastic Defense, 1933

Back to Table of Contents -- Combat Studies Research # 2

Back to Combat Studies Research List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com