In 1941, the German Army's doctrine for defensive operations was nearly identical to that used by the old Imperial German Army in the final years of World War I. The doctrinal practice of German units on the Western Front in 1917 and 1918 -- the doctrine of elastic defense in depth -- had been only slightly amended and updated by the beginning of Operation Barbarossa. In contrast to German offensive doctrine, which from 1919 to 1939 moved toward radical innovation, German defensive doctrine followed a conservative course of cautious adaptation and reaffirmation. Consequently, although the German Army in 1941 embraced an offensive doctrine suited for a war of maneuver, it still hewed to a defensive doctrine derived from the positional warfare (Stellungskrieg) of an earlier generation.

Elastic Defense: Legacy of the Great War

Elastic Defense: Legacy of the Great War

The Imperial German Army adopted the elastic defense in depth during the winter of 1916-17 for compelling strategic and tactical reasons. At that time, Germany was locked in a war of attrition against an Allied coalition whose combined resources exceeded those of the Central Powers. The German command team of Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff hoped to break the strategic deadlock by conducting a major offensive on the Russian Front in 1917. Therefore, they needed to economize Germany's strength on the Western Front in France and Belgium, minimizing casualties while repelling expected Allied offensives.

General Erich Ludendorff. Ludendorff's sponsorship caused the Elastic Defense to be adopted by the Imperial German Army during the winter of 1916-17.

To accomplish this, they sanctioned a strategic withdrawal in certain sectors to newly prepared defensive positions. This Hindenburg Line shortened the front and more effectively exploited the defensive advantages of terrain than did earlier positions. This withdrawal was a major departure from prevailing defensive philosophy, which hitherto had measured success in the trench war solely on the basis of seizing and holding terrain. In effect, Ludendorff*

(*Hindenburg and Ludendorff nominally operated according to the dual-responsibilty principle of the German General Staff, whereby the commander and his chief of staff shared responsibility and authority on a nearly equal basis. In practice, Ludendorff's energies were so great that Hindenburg regularly deferred to his judgment. Ludendorff also routinely involved himself in matters of technical detail far beneath the Olympian gaze of Hindenburg. In the matters being discussed, Ludendorff thus played the dominant role at both the strategic and tactical levels.)

adopted a new policy that emphasized conserving German manpower over blindly retaining ground -- a strategic philosophy whose tactical component was an elastic defense in depth.

Through the war's first two years, German (and Allied) doctrinal practice had been to defend every meter of front by concentrating infantry in forward trenches. This prevented any enemy incursion into the German defensive zone but inevitably resulted in heavy losses to defending troops due to Allied artillery fire. Such artillery fire was administered in increasingly massive doses by the Allies, who regarded artillery as absolutely essential for any successful offensive advance. (For example, even the stoutest German trenches had been almost entirely eradicated by the six-day artillery preparation conducted by the British prior to their Somme offensive in 1916.) Consequently, the Germans sought a defensive deployment that would immunize the bulk of their defending forces from the annihilating Allied cannonade.

The simple solution to this problem was to construct the German main defensive line some distance to the rear of a forward security line. Although still within range of Allied guns, the main defensive positions would be masked from direct observation. Fired blindly,

most of the Allied preparatory fires would thus be wasted.

In developing the Elastic Defense doctrine, the Germans analyzed other lessons of trench warfare as well. The German Army had realized that concentrated firepower, rather than a concentration of personnel, was the most effective means of dealing with waves of Allied infantry. Too, the Germans had learned that the ability of attacking forces to sustain their offensive vigor was seriously circumscribed. Casualties, fatigue, and confusion debilitated assaulting infantry, causing the combat power of the attacker steadily to wane as his advance proceeded.

This erosion of offensive strength was so certain and predictable that penetrating

forces were fatally vulnerable to counterattack-provided, of course, that defensive reserves

were available to that end. Finally, the Allied artillery, so devasting when laying prepared

fires on observed targets, was far less effective in providing continuous support for

advancing infantry because of the difficulty in coordinating such fires in the days before

portable wireless communications. Indeed, because the ravaged terrain hindered the timely forward displacement of guns, any successful attack normally forfeited its fire support once it advanced beyond the initial range of friendly artillery. [2]

Between September 1916 and April 1917, the Germans distilled these tactical lessons into a novel defensive doctrine, the Elastic Defense.

[3]

This doctrine focused on defeating enemy attacks at a minimum loss to defending forces rather than on retaining terrain for the sake of prestige. The Elastic Defense was

meant to exhaust Allied offensive energies in a system of fortified trenches arrayed in depth.

By fighting the defensive battle within, as well as forward of, the German defensive zone, the Germans could exploit the inherent limitations and vulnerabilities of the attacker while

conserving their own forces. Only minimal security forces would occupy exposed forward trenches, and thus, most of the defending troops would be safe from the worst effects of the fulsome Allied artillery preparation.

Furthermore, German firepower would continuously weaken the enemy's attacking infantry forces. If faced with overwhelming combat power at any point, German units would be free to maneuver within the defensive network to develop more favorable conditions. When the Allied attack faltered, German units (including carefully husbanded reserves) would counterattack fiercely. Together, these tactics would create a condition of tactical "elasticity": advancing Allied forces would steadily lose strength in inverse proportion to growing German resistance. Finally, German counterattacks would overrun the prostrate Allied infantry and "snap" the defense back into its original positions.

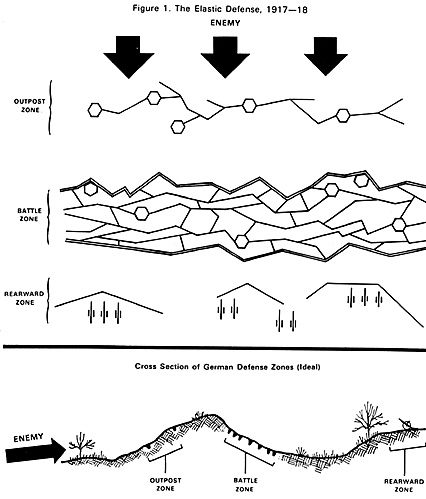

The Germans accomplished this by designating three separate defensive zones -- an outpost zone, a battle zone, and a rearward zone (see figure 1). Each zone would consist of a series of interconnected trenches manned by designated units. However, in contrast to the old rigid linear defense that had trenches laid out in parade-ground precision, these zones

would be established with a cunning sensitivity to terrain, available forces, and likely enemy action.

The outpost zone was to be manned only in sufficient strength to intercept Allied patrols and to provide continuous observation of Allied positions. When heavy artillery fire announced a major Allied attack, the forces in the outpost zone would move to avoid local artillery concentrations. When Allied infantry approached, the surviving outpost forces would disrupt and delay the enemy advance insofar as possible.

If a determined Allied force advanced through the outpost zone, it was to be arrested and defeated in the battle zone, which was normally 1,500 to 3,000 meters deep. The forward portion of the battle zone, or the main line of resistance, was generally the most heavily garrisoned and, ideally, was

masked from enemy ground artillery observation on the reverse slope of hills and ridges. In addition to the normal trenches and dugouts, the battle zone was infested with machine guns and studded with squad-size redoubts capable of all-around defense.

When Allied forces penetrated into the battle zone, they would become bogged down in a series of local engagements against detachments of German troops. These German detachments were free to fight a "mobile defense" within the battle zone, maneuvering as necessary to bring their firepower to bear. [4]

When the Allied advance began to founder, these same small detachments,

together with tactical reserves held deep in the battle zone, would initiate local counterattacks. If the situation warranted, fresh reserves from beyond the battle zone also would launch immediate counterattacks to prevent Allied troops from rallying.

If Allied forces were able to withstand these hasty counterattacks, the Germans would then prepare a deliberate, coordinated counterattack to eject the enemy from this zone. In this coordinated counterattack, the engaged forces would be reinforced by specially designated assault divisions previously held in reserve. If delivered with sufficient skill and

determination, these German counterattacks would alter the entire complexion of the defensive battle. In effect, the German defenders intended to fight an "offensive defensive" by seizing the tactical initiative from the assaulting forces. [5]

The rearward zone was located beyond the reach of all but the heaviest Allied guns. This zone held the bulk of the German artillery and also provided covered positions into which forward units could be rotated for rest. Additionally, the German counterattack divisions assembled in the rearward zone when an Allied offensive was imminent or underway.

In summary, in late 1916, the Imperial German Army adopted a tactical defensive doctrine built on the principles of depth, firepower, maneuver, and counterattack. The Germans used the depth of their position, together with their firepower, to absorb any Allied offensive blow. During attacks, small German units fought a "mobile defense" within their

defensive zones, relying on maneuver to sustain their own strength while pouring fire into the Allied infantry. Finally, aggressive counterattacks at all levels wrested the tactical initiative from the stymied Allies, allowing the Germans finally to recover their original positions.

Using the new defensive techniques, the Imperial German Army performed well in the 1917 battles on the Western Front. In April, the massive French Nivelle offensive was stopped cold, with relatively few German losses. The British also tested the German defenses with attacks in Flanders at Arras and Passchendaele. Although the British enjoyed some local successes, no serious rupture of the German defensive system occurred.

Throughout the 1917 battles, the Germans modified and refined the Elastic Defense: among other changes, the battle zone was deepened, heavy machine guns were removed from the static redoubts to provide suppressive fire for the local counterattacks, and German artillery was encouraged to displace rapidly to evade counterbattery fire.

[6]

On the whole, however, the novel system of elastic defense in depth was

thoroughly vindicated. As the German Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm remarked in his memoirs, "Had we held to the stiff defense which had hitherto been the case [rather than the Elastic Defense system], I am

firmly convinced that we would not have come victoriously through the great defensive battles of 1917." [7]

One ominous development that seemed to challenge the continued effectiveness of the Elastic Defense was the British tank attack at Cambrai in November 1917. There, massed British tanks broke through the entire German defensive system, and only the combined effects of German counterattacks and British irresolution restored the German lines. This wholesale use of tanks to sustain the forward advance of an Allied attack

seemingly upset the logic on which the German defensive concept was based.

Although insightful in other aspects of battlefield lore, the Germans mistakenly discounted the combat value of tanks despite the Cambrai incident. While the Germans were impressed by the "moral effect" that tanks could produce against unprepared troops, they also felt that local defensive countermeasures (antitank obstacles, special anti-armor ammunition for rifles and machine guns, direct-fire artillery, and thorough soldier training) virtually neutralized the offensive value of the tank.

[8]

In the German assessment, tanks were similar to poison gas and flamethrowers as technological nuisances without decisive potential. [9]

The Germans minimized the British success at Cambrai by stating that it was the result of tactical surprise, achieved by the absence of the customary ponderous artillery preparation, rather than from the tank attack itself. In consequence, no reassessment of the Elastic Defense was deemed necessary, and none was undertaken. For example, the updated version of the German doctrinal manual for defensive operations published in 1918 made no special reference to tank defense. [10]

To complement his strategic designs, Ludendorff directed the implementation of the Elastic Defense doctrine. [1] This new doctrine supported the overall strategic goal of minimizing German casualties and also corresponded better than previous methods to the tactical realities of attack and defense in trench

warfare.

To complement his strategic designs, Ludendorff directed the implementation of the Elastic Defense doctrine. [1] This new doctrine supported the overall strategic goal of minimizing German casualties and also corresponded better than previous methods to the tactical realities of attack and defense in trench

warfare.

Back to Table of Contents -- Combat Studies Research # 2

Back to Combat Studies Research List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com