The mounted knight, resplendent in his polished armor was king of the battlefield. The simple peasant, armed with a short sword or more likely just a flail from his farm, was fodder for the same field. There should be a monument somewhere for the first peasant, who, about to be ridden down by a knight, whipped out his matchlock and put an eighty caliber ball through that smug steel-covered face. Whether surprise or death overcame him first, we will never know.

The mid 1840s and 1850s saw a great westward migration of the American people. The weapons they carried were similar to, but different, from that used in war at the time, but saw more real use in daily life. These weapons would be the technology by which the West was "won".

The single-shot, muzzle loading rifle had just about reached the height of its perfection. It had grown out of the German Jaeger rifle of the pre-Revolutionary days into the famous American long rifle. Sometimes called the Kentucky rifle or Pennsylvania rifle, it was really the product of American ingenuity and need. The caliber of the gun had decreased from .80 to as small as .38 to conserve both lead and powder on the frontier.

The barrel was long to increase accuracy and the stock beautifully carved out of curley maple. The only true American addition was the hinged patch box on the stock. Originally a flintlock, this rifle used cap and ball.

To fire the rifle, or any other muzzle loading firearm, a specific procedure had to be followed. First, the right hand removed a paper cartridge from the cartridge box worn on the belt on the right front side. The cartridge contained the proper amount of powder needed for one shot as well as the lead ball. Second, the cartridge was torn open with your teeth and the ball was grasped between the thumb and forefinger of the left hand while the rifle was held muzzle upward. Then the powder from the cartridge was poured from the cartridge into the barrel of the piece, and the paper discarded. Following this, again with the right hand a greased patch was removed from the cartridge box and placed over the muzzle of the gun, indenting it slightly to form a cup.

The ball was placed in the cup and pushed gently until the patch and ball were seated in the muzzle. Then the ball and patch were rammed into the barrel with the ramrod. After removing the ramrod (which was sometimes not removed leading to untimely accidents). The weapon was raised to waist level and the hammer cocked back half way. A brass percussion cap was placed over the exposed nipple. Then the rifle was raised to shoulder level, the hammer cocked back all the way and the trigger pulled. If everything went correctly, the gun fired.

The skilled marksman could do the above in about fifteen seconds, and within three minutes put ten balls inside a ten inch circle at three hundred yards.

Many wagon trains heading west took trade guns to be sold to the Indians. They were generally not as carefully made and finished as standard weapons, and some were so bad that they soon burst or wore out. In the early days, the Indians preferred flintlocks to percussion cap guns since flints could be picked up off the ground and caps were expensive. The first trade guns were distinguished by deep trigger guards, a decoration on the butt stock in the shape of a brass serpent, and often brass studs in the stock; later the Indians insisted on these characteristics on any gun they bought.

As the frontier moved out of the forest and onto the plains of the West, a new type of firearm was needed. To start with the guns needed to be shorter because of the terrain and the need for a weapon usable on horseback. Game was also larger, requiring a more powerful weapon. It was provided by Sam and Jay Hawkin of St. Louis. They made a rifle that was shorter, heavier and had heavily strengthened breeches. They beefed up the wrist portion so the stock would not break if you or it fell from a horse. The Hawkins rifle had a gain twist rifled barrel and fired a ball somewhere between .53 and .55 caliber.

The standard plains rifle had the following specifications:

- Barrel: 28 - 38 long, soft iron with slow spiral rifling

Caliber: .45 -.55

Charge: 100 grains (although some were fired with 215 grains!)

Weight: 15 pounds

Henry Chatillion of the American Fur Company could regularly drop a buffalo with a clean shot through the lungs at three hundred or more yards, and a hunter named Lewis winged a Digger on the dead run at over two hundred yards. Whether he carried a rifle and knife or not, almost no man headed West without a handgun, and these were a mixed lot. They ranged from old single shot cap and ball pistols to the newest Colt revolver.

For the pioneer starting from the East coast, most pistols fell into two categories. The first was the older type, and it consisted of nothing more than grandfather's old pistol now re- worked for a cap lock. It looked like the traditional dueling pistol although it was not as fancy. With its relatively light weight and mammoth bore (.50 to .55 caliber), it must have been a wrist breaker to shoot. The first thing anyone starting for the West would have done with this pistol would have been to get rid of it in favor of anything that held more than one shot.

The one that the storekeeper or homeowner was most probably familiar was the pepperbox. This little creature had been developed in 1836 by Benjamin and Barton Darling of Shrewsbury, Massachusetts. It was a single hammer, single action weapon with six revolving barrels. By the next year, Ethan Allen of Grafton, Massachusetts was making a similar gun with double action. The average pepperbox was about eight inches long with six .40 caliber barrels. With a three and one half inch barrel, the maximum effective range must have been measured in feet rather than yards, but to the cat burglar suddenly faced by six barrels five inches from his nose, maximum range probably meant very little. The only danger with this pistol was its tendency to fire all six shots at once. The result was a spectacular hail of lead.

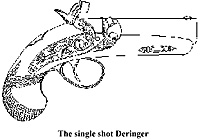

For the gambling man, the only way to go was with his Derringer. This pocket sized weapon was developed by Deringer in 1830 (Note that the spelling of the man's name is with one "r" while the name of the pistol has two. There is a reason for

this. Copies of Deringer's weapon were widely made. In order to avoid patent cases, these pirated weapons were labeled "Derringer" pistols. The double r spelling has since become accepted even for those made by the original Deringer). These

little pistols could be as small as three and three quarter inches long and .33 caliber. As such, they could easily be concealed under a belt or up a sleeve. Like the pepper box, they were of extremely limited range. But then, if you wanted to kill a man at long range, you would use something else.

For the gambling man, the only way to go was with his Derringer. This pocket sized weapon was developed by Deringer in 1830 (Note that the spelling of the man's name is with one "r" while the name of the pistol has two. There is a reason for

this. Copies of Deringer's weapon were widely made. In order to avoid patent cases, these pirated weapons were labeled "Derringer" pistols. The double r spelling has since become accepted even for those made by the original Deringer). These

little pistols could be as small as three and three quarter inches long and .33 caliber. As such, they could easily be concealed under a belt or up a sleeve. Like the pepper box, they were of extremely limited range. But then, if you wanted to kill a man at long range, you would use something else.

Colt

The most popular handgun on the plains was the Colt. The revolver had been introduced to the world strapped to the hip of the Texas Rangers in the mid 1830's. It was the only sidearm capable of giving the outnumbered Texans any chance against the Indians who inhabited their land. Colt was unable to interest the American government in the new pistol and had gone out of business by the time the war was with Mexico suddenly called for his skills. Since 1846, any sane man heading West immediately purchased a Colt, and it could mean the difference between life or death on the plains.

One other gun found on the way West was the shotgun. The cardboard cartridge had been developed in the mid 1830's and the choke bore in the 50's. Although the shotgun was mainly a bird gun, many a pioneer on the Oregon Trail stashed it on the seat of his covered wagon. Known later as the scatter gun, it became the standard weapon for stage drivers, sheriffs, and television lawmen. One other weapons was as ubiquitous as leather boots and hats. Whereas the belt ax or tomahawk had been common among the woodsman of the East, it did not count for much on the plains.

Since there were few trees on the prairie, its chopping ability meant little, and for war the Indians preferred their own version of the medieval mace. This was a double-pointed stone club mounted on a supple three foot wooden handle. It was an excellent weapon for close combat on horse back. After the 1830's the tomahawk was used almost exclusively as a ceremonial instrument. Of these, the pipe tomahawk was highly prized by those Indians fortunate enough to obtain one. Many of these had all-brass heads, and some were of pewter. Those still made of iron or steel developed thin blades without an edge.

By the mid-50's, no American male west of Independence, whether old hand or greenhorn, would be caught dead without his Bowie knife.

This weapon, named after Colonel James Bowie of Alamo fame, had gained such popularity by the middle of the century that even English table knives were made in its pattern. Officially, it was a steel knife with a blade about fifteen inches long which was suitable for self-defense or general camp/trail work. It could be used for trimming light branches, opening an animal or enemy's skull, jointing wild game of all sizes, or digging in the ground. It was single-edged with a false edge along the back for a few inches. This feature allowed a backstroke in combat. The back of the blade curved down to meet the front in a concave arch. Since it was a fighting weapon, the handle had a guard. Stories of the mystic qualities of the knife were legion, but like most weapons, its successful use depended more on the skill of the person holding it than anything else.

It was with these weapons that the great migration of westward pioneers secured their persons, their property and their safety.

Back to Cry Havoc #8 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com