Pneumonic Plague

As the Black Death continued unchecked a change in its methods of transmission took place. As the sick became more numerous, some survived long enough to develop the infection in their lungs. Now the disease was no longer limited to the rat-flea- man cycle with its 50-75% mortality rate, but as pneumonic plague 100% fatal, as well. Both forms were lethal, but the pneumonic form could strike with an abruptness that added to the terror the disease evoked. Numerous chronicles from all over Europe tell of persons going to bed in health and never wakening, of doctors catching the illness at the bedside and dying before the patient and of persons in normal conversation who dropped dead in midsentence. As the death toll mounted, even the expression of grief became a cause for concern by the authorities. Seeking to stem public panic, officials forbade the ringing of bells, the wearing of black except by widows and restricted funerals, when they were actually held, to only two mourners.

The Black Death, with its great mortality and its seeming sentence of death for all whom came in contact with it caused a warping of the collective medieval mortality which brought with it both a sense of a vanishing future and a dementia of despair.

The plague was not the kind of calamity to inspire man to greater heights of altruism. Its loathsomeness and deadliness did not herd people to together in an air of mutual distress, rather it prompted their desire to escape one another.

Angelo di Tura, a chronicler of Siena, described the atmosphere as one in which "Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another for this plague seemed to strike through rough breath and sight, so they died. And no one could be found to bury the dead for money or friendship." The scene he described would be echoed across all of Europe. Guy de Chauliac, the Papa l physician and the "father of surgery" was more blunt in his assessment "A father did not visit his son, nor the son his father. Charity was dead."

Those who could, primarily the wealthy, sought safety in flight, leaving the urban poor to die in their burrows. But even though the death rate was higher among the poor, the rich and the powerful also died. Alfonso XI of Castile was the only monarch killed, but his neighbor Pedro of Aragon lost his wife, a daughter and a niece in the space of six months. The Byzantine Emperor lost his son. Charles IV's wife Jeanne and her daughter in law, the wife of the Dauphin also succumbed. Jeanne, the Queen of Navarre and daughter of Louis X was another victim. Edward III's second daughter, Joanna, died of it in Bordeaux while on her way to marry Pedro, the heir of Castile. In England the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Stratford died in August 1348, his successor died in May 1349 and the next appointee three months later. Curious sweeps of mortality affected some bodies of London merchants. All eight wardens of the Company of Cutters, all six of the Hatters and four wardens of the Goldsmiths died. Sir John Pulteney, master draper and four times Mayor of London was a victim as was Sir John Montgomery, Governor of Calais.

The death rate was highest among the clergy and the doctors whose professions brought them in close contact with the sick and dying. Out of 24 physicians in Venice, 20 lost their lives in the plague. Clerical mortality varied with rank. Prelates managed to sustain a higher survival rate than the lesser clergy. Among bishops the death rate has been estimated at one out of six. Priests died at a rate closer to one out of two.

Government officials found no special immunity and their loss contributed to the general chaos. In Siena, four of the nine members of the governing oligarchy died. In France one third of the royal notaries succumbed while in Bristol 15 out of 52 members of the Town Council died.

"This is the end of the world."

Adding to the terror of the seemingly unstoppable march of death was its unknown origin. The absence of an identifiable earthly cause gave the plague supernatural and sinister qualities. The role of rats and fleas as vectors in the transmission of the disease was never suspected. There were several reasons for this.

Both were common in the period and had achieved a familiar anonymity. There must have been great die offs of rats, who would have been struck by the plague first, but if there were, no one saw it as sufficiently unusual to comment on it. Confusing any attempt to associate these common medieval vermin with the disease striking Europe was the fact that the plague was also being spread by respiratory infection. And, finally and simply stated, the medieval mind was unable to make the connection. Besides there were other possible causes that better fit their preconceived notions of the way the universe was ordered.

An earthquake, which had a carved a path of wreckage from Naples to Venice in the summer of 1347, was blamed for releasing gases into the air which poisoned all on whom they fell. The scholars of the University of Paris stated that the Black Death resulted from "a triple conjunction of Saturn Jupiter and Mars in the 40th degree of Aquarius occurring on the 20th of March 1345", but added that they did not know how.

No one really believed them anyway. To the common people there could only be one source of a thing as sweeping and as total as the Pest the wrath of God punishing mankind for its sins. There was official support for this feeling. In a bull of 1348 Clement called the Plague, "a pestilence with which God is afflicting his Christian people." Philip believed that God was punishing France for her sins and issued a unusual public health decree against blasphemy. For the first offense a man was to lose a lip, for the second the other lip and for the third, the tongue itself.

Others saw it as more than just an expression of divine displeasure and chastisement. The Italian chronicler Matteo Villani spoke for them when he said the plague was "Divine action with no goal less than the extermination of mankind." Another monk, writing hurriedly in his journal said it best "This is the end of the world."

Impact of the Black Death

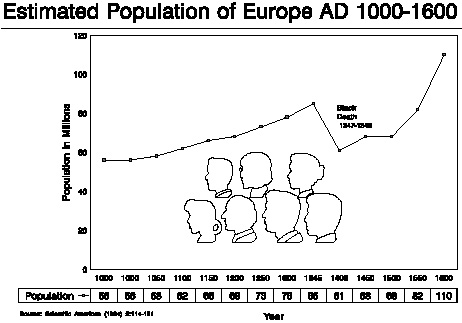

The Plague continued to beset Europe in waves of recurrences, striking mostly at children, until it disappeared from Europe in 1399, not to return again until the 17th century, leaving behind it a major alteration to the demography and population dynamics of Europe that was to continue for generations. Europe's population continued to shrink, declining further so that at the end of the 14th Century the population was half that of 1345. It would require 100-133 years or about 5 to 6 human generations for Europe to absorb the shock of exposure to the plague in both its initial visitation and in its recurrences. In England the Poll Tax of 1377 counted 2 million persons. Since the minimum in 1345 was 3.5 million it meant that 1.5 million had died and England would take until the middle of the 16th Century to reach the population she had in 1345.

The Black Death struck at a world already in motion and greatly accelerated the changes that other pressures were beginning to bring on the fabric of medieval society. Social structures which had been breaking down since the beginning of the 13th century collapsed. In the countryside the first most obvious effect of the Black Death was a severe shortage of labor. A large part of the land passed out of cultivation. Landlords halted the process of emancipating serfs and tried to exact the old burdensome labor services from their tenants. Free laborers tried to take advantage of the shortage of workers to demand higher wages and governments responded with repressive measures fixing wages at the old levels.

Traditional farming arrangements in villages all over Europe were thrown into chaos by the sudden extinction of many families, the failure of heirs in others and the unprecedented surplus of land.

For the first time there was an outbreak of religious fervor among the common people aimed at establishing a sort of democratic, socialist heaven in this world, not just preparing man for the next. When the peasants hopes for a better life were repressed by the governments and the landlords, they rose in violent rebellions. The French Jacquerie of 1358, and the English Peasant's Rebellion in 1381 led by Wat Tyler . None of these rebellions was immediately successful but in the end the continued shortage of agricultural labor in relation to the land available for cultivation brought about changes that could not be achieved without violence. The disintegration of the manor had begun and Lords replaced the requirement of labor services from a deeply reluctant and depleted peasantry with the acceptance of money rents, while acknowledging the freedom of their laborers.

In the sphere of urban life and commercial activity, the immediate impact was to create an oversupply of goods and a sharp drop in overall demand. With the reduction of the available labor pool prices for labor rose to all time highs creating run away inflation. The middle class responded the same as the landholder in their response and tried to hold on to what they had and keep the lower classes in their place by enacting restrictive guild regulations and city ordinances.

In the past anyone could be apprenticed, now the guild membership was made hereditary. The result was a growth of a large class of proletarian laborers, living at the mercy of their masters and forbidden to organize to defend or further their own interests. Frustrated they responded with city riots comparable in violence to the peasant rebellions. New aggregations of capitalist wealth arose. While the volume of trade decreased in 1350 (a much smaller population would tend to produce and exchange fewer goods),. It is not so clear that there was a fall in per capita production or consumption and in some areas some industries prospered greatly despite the general decline. In England, a highly profitable cloth-manufacturing industry grew up based on a new technique which used the power of water mills.

Governments were forced to turn inward. As land was abandoned, rents fell off or were unpaid. The yield from taxes declined drastically. Philip was unable to collect more than a fifth of the subsidy granted him by the Estates in the winter of 1347-8. The resulting shortage of both men and money had a dampening effect on large scale military operations by the English and French monarchies.

The loss of manpower and taxes led both the French king and the French lords to accept the concept of a paid army, recognizing that the warrior's function was now a trade for at least the poorer knights if not the grand seigneurs.

Rates of Pay

Rates of pay were set (40 sous a day for a banneret, 20 for a knight, 10 for a squire, 5 for a valet, 3 for a foot soldier and 2 1/2 for an armor bearer or other attendant). Coming at a time when taxes were lower than previously, this led to smaller armies.

The Church, which had bound Europe together, was at first materially strengthened by the benefices left her by the plague victims. But survivors of the plague could discover no Divine purpose in the pain they had suffered. While the ways of God were always mysterious the scourge of the Plague had been too terrible to be accepted without questioning. If a disaster of this magnitude was a mere wanton act of God with no discernible purpose then reliance on God's goodness was no longer an absolute. Once people envisioned the possibility of change in the fixed order, the age of unquestioned submission was over. Minds opened to admit these questions could never be shut again. The Black Death may have been the unrecognized beginning of modern man. Certainly the Church lost prestige and with it much of her power.

Attacks on the clergy increased and for good reason as many had been hastily ordained in an attempt to fill the gaps left by the great death of the parish priests. Most were incompetent, uneducated and immoral. Leading to the spread of anticlericalism. When Henry II had spoken hasty words in 1170 that lead to the death of Thomas a' Becket, the power of the Church and the peasants loyalty to it was sufficient to force the King of England to submit to penance by flagellation at the hands of the canons of Canterbury Cathedral. By contrast in 1381, Simon Sudbury, Becket's successor as Archbishop of Canterbury, was beheaded surrounded by a crowd of peasants which cheered, applauded and made ribald comments as the executioner's ax fell, and the Church could do little more than protest.

Impact on the Hundred Years War

The Black Death, the greatest catastrophe in European History, had surprisingly little impact on the Hundred Years War. It only seems to have delayed the war a few years, while the national governments tried to suppress rising discontent and reduced the overall size of the armies that would campaign afterwards.

There were some reasons for this. There were no French or English armies in the field when the plague struck. Had there been one or both might have suffered the same fate as that of a Scottish army at Selkirk. Separated from the plague by a winter's immunity, the Scots had gathered to attack the "southrons". With spring the plague came to the Scottish army. Within a few days half had died or were dying. The survivors fled and took the epidemic with them to the countryside. For the French and English there was no such calamity. The Pest did not selectively impact one army or the other nor did it have an opportunity to direct itself against a military assemblage in either country.

Consequently the loss in military men was roughly proportional to the population and approximately the same, proportionally, in each country. Had either country lost its military in a manner similar to the Scots, the disaster of the loss of trained personnel especially in France due to its dependence on men at arms and the losses at Crecy, would have been a death blow. Had France lost its remnants of its army in this manner, it is unlikely that they would have been able to recruit and train sufficient military forces to resist the English especially as they seemed devoted to the old tactics. Had the English lost its army, they might have been compelled to settle for what they had gained or even possibly lost all, including Aquitaine and Gascony, much earlier.

In 1350, after the last of the dead had been buried, the military situation had not changed significantly. Both sides possessed the same advantages and disadvantages. While the armies that would clash over the next century were smaller, their sizes relative to one another remained the same. The elements of the formula that had allowed England to achieve the upper hand better leadership, better access to resources, better tactics remained. In France, the inept Philip VI died and was replaced by the more inept John the Good who continued the tradition of Valois ineptitude and inability to learn from the failures of Crecy and Calais.

France was, as it had been in the summer of 1347, in turmoil and unable for the next half century to do anything to stop the systematic plunder of the country.

Back to Cry Havoc #8 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com