Very often wargamers and military history buffs become bogged down in the minutiae of weapons, logistics, and campaigns and forget that real flesh and blood men were involved in what are now "paper exercises." Occasionally however a writer exists who puts everything in context without losing the flavor of the fact that these are men (and women) whose job is war. One of the best, as Flynn explains here, is Rudyard Kipling.

In any examination of British Imperial India, one must eventually encounter the preeminent storyteller of the era, Rudyard Kipling. His poetry and prose reflect his uniquely accurate viewpoint and depict India as it was under the British imperium. More to the point, he paints a portrait of contemporary British military life that is vivid and sympathetic without being maudlin.

Born to the Raj

Rudyard Kipling is one of the few men unequivocally qualified to present this time period because he was fully part of it. Born in Bombay on December 30, 1865, he spent the first five years of life in India where he was brought up by and with the native servants and, as a child, spoke Hindustani better than English. Taken to England, he endured the rigors of a fully British education (with all that that entails) until gratefully returning to his beloved India at age 17. It was during this boyhood trip back home that he began writing stories about life in the colonies. Because of his Indian upbringing Kipling did not become an archetype of the typical British outlook but maintained an ability to view both sides objectively. Kipling's training as a writer and reporter allowed him to express the situation in India from a vantage point that none of his contemporaries could. Hence, his works are only barely touched by the overbearing ego incorporated into him from his schooling. Kipling may have been British, but he was fully attuned to the Indian viewpoint.

Kim

Kim is a richly descriptive work that describes how under the self-righteous Raj of the Nineteenth Century's industrial giant and super power, Britain, half-naked beggars fill the streets of India. The novel portrays the milieu of British India, capturing the spice-filled, noisy, clamoring and muggy atmosphere of an early morning bazaar and providing gastronomic detail about the cultural food. It also opens to the reader the Indian view of the British and vice versa.

Kim reveals how the military elite have replaced the Indian nobility as the favored class and established their own place in society as the new Brahmins. It tells how a British bureaucracy has carefully removed power from the natives in order to rule in their place, and communicates how, though every action is performed for Britain herself, the actual influence of the far off isle is dilute and sometimes ambiguous. It even subtly reveals how morality has become less clear and more a gray area where privilege often serves to sway the verdict.

Kim also provides a wealth of information about India's caste system and the native social structure. It tells how Hinduism's world view had led to a society that is, at least from the Western view, unbearably rigid and bereft of hope. A social order in which no matter what level you are born at, be it pauper or prince, you are locked into it and may not raise or lower yourself through marriage or the accumulation of money or power. It is a vicious cycle based upon the idea of continuous reincarnation into high levels until you return to the bottom and start again. Kim reveals a native system that precludes the lower classes from accumulating wealth or power and in which they are spat upon, degraded and treated as pariahs by the entire social structure.

This regimented lifestyle is brutally exposed in Beyond the Pale; a tale of forbidden love between an officer and an Indian widow. Their romance, doomed from the start by this straitjacketed society, ends with the widow having her hands cut off and the officer nearly being killed by an attackers knife. Their crime: mutual attraction.

Although in Kipling's tale above, British interference resulted in the loss of appendages for one woman, the effect of their presence was a great deal more widespread than that. Britain originally came to India seeking new markets for their industries and access to rich and abundant natural resources. However, like many of the "primitive" nations Britain attempted to assimilate, India resisted violently at times (i.e. The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857). Thus, while the true motivation was economic, the presence became at times a burdensome military occupation of the subcontinent, with the associated wear and tear on occupier and occupied. The Indians eventually grew accustomed (though not necessarily satisfied) with the status quo and India, although dependent upon British exports and exploited for her cheap labor force, prospered.

Kipling & The Army

Kipling truly comes into his own when he deals specifically with the military. It seems to be his first love and his lasting passion and he describes the military and the men that comprise it with majesty, emotion, and power. These qualities make Kipling's portrait of the British military and their relationships with themselves, the system and the native population one of living, breathing men. The British military could at times, be brutal and harsh in their dealings with the natives, but as Kipling points out, they also kept the peace and enforced British laws and policies that were a bit more civilized than traditional methods.

Under British rule, the nobility was displaced in favor of ranking officers; new and fairer laws were enacted and enforced; the economy improved; and a greater de facto unity than had been possible before was achieved, partially through the introduction of Indians into the British army. All of these changes are chronicled in Kipling's magazine articles, stories and poems. Two strong examples of this can be found in his short story The Watch; a telling tale of a native's decision concerning an officer's lost pocket watch and The Grave of the Hundred Head; a deep, sorrowful story of bitter vengeance enacted by the First Shikaris against enemies for the killing of their English lieutenant.

From duty, as in Snarleyow to betrayal, cowardice and swift punishment for those of these unsoldierly virtues, as in Danny Deever, Kipling touches all aspects of life in the military. Kipling's military narrative poems describing battles, soldiers, or the life of fighting men, e.g. The Grave of the Hundred Head, Tommy, Fuzzy-Wuzzy, That Day, The Shut-Eyed Sentry, and the immortal Gunga Din, portray accurately and without interfering bias (except when used as a literary technique) the compassion and depth of emotion that Kipling's feels towards these uniformed servants of the Queen..

Snarleyow is a fierce, brutally moving piece about true sacrifice and duty to one's country. The poem concerns a driver who, knowing that the only way the battle can be won is to charge now, is forced to roll over the still alive but half-crushed body of his brother. The poem closes with the assertion that

- The moril of this story, it is plainly to be seen:

You 'avn't got no families when servin'; of the Queen

You 'avn't got no brothers, fathers, sisters, wives, or sons

If you want to win your battles take an' work your bloomin' guns!

Gunga Din is one of Kipling's best known works. It has been oft quoted and misquoted and the Hollywood version does little justice to this wonderful piece of poetry. The poem details the relationship between one rugged and jaded infantryman and a put upon but respected Indian "water boy." It tells of the trust the company has in him. The respect and loyalty is returned as this servant, little more than a slave, saves the wounded narrator, only to die from a bullet wound himself as he discharges this final task. There is real feeling in the narrator's final words when he says:

- Though I've belted you and flayed you,

By the livin' Gawd that made you,

You're a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

The Common Soldier's Lot

As Kipling shows us the life of the soldiers was, at times, deplorable. The common infantryman was mistreated or looked down upon by most of society. For solace they turned to loose women and drink, increasing the scorn of the elements of society that drove them to these levels. Tommy has the soldier narrator decry the hypocrisy of a social structure that allows the people he protects to deny them entrance into their establishments, homes and businesses, but expects him to lay down his life for them as soon as danger appears.

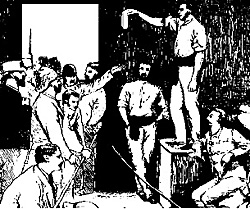

British soldiers auction captured loot, 1879.

British soldiers auction captured loot, 1879.

Often, facilities in barracks were a joke and there were literally no amenities during maneuvers in preparation for battle. When free time was available, most men had already gambled away what little pay they had. Some took to looting the villages they conquered or stealing from defenseless natives. This kind of activity is given review in Kipling's Loot; in which an experienced infantryman expounds upon the pros and cons of looting. Advancement was often slow and almost impossible unless you bought your way into an officer's billet. Surprisingly though, the men's loyalty to their officers, however spoiled and incompetent they might be, could be strong as exemplified in The Shut-Eyed Sentry. In this tale, a sentry pretends not to notice an officer's drunkenness. When official inquiries are made the entire company signs affidavits that the man was sober.

Military discipline was swift, harsh and merciless. The punishment for killing a fellow soldier was hanging and a scenario dealing with exactly that is played out in the sorrowful Danny Deever in which a green recruit asks his officers what is occurring as Danny is dragged up the gallows steps and executed. Although most of Kipling's poems concerning enlisted life are depressing and depict an unsavory existence, the lot of the common soldier was several orders higher than that of the average Indian citizen and his social status was equally higher.

Despite his journalistic training and knowledge of both cultures, Rudyard Kipling was a proud Englishman and thus his views are slightly but significantly colored. His writing at times is noticeably affected by his pride in his country, his faith in Britain as the civilizer of India, and his attitude that "the sun never sets on the British Empire." However, this does not stop him from recognizing and reporting stupidity, sloth, and cruelty no matter where he saw it. This is easily observable from the fact that though he had great faith and respect in the British officer class, he published several short stories and a fair number of poems ridiculing them. And even he foregoes pride when he writes his poem the White Man's Burden which has a cutting and sarcastic bent to it in it observation of Imperialism in action and essence. Thus, while Kipling's occasionally colored views are present, they neither alter the truth of his stories, nor does it handicap him from seeing both sides of the issues he confronts in the colonies.

Understanding India under the aegis of British Imperialism, requires a knowledge and appreciation of the works of Rudyard Kipling. His contribution to chronicling his era is enormous and literally without equal in this specific subject. His works are alternately praised for their accuracy or cursed for their bias but that is a subject best left to literary critics. What matters is that there is a vast and extensive body of work detailing a specific land and covering and era that has few chroniclers. And even more significant is the fact that it is not a body of work looking back upon a time. Instead it is a primary source, composed of the first hand reactions and anecdotal tales of a man who was intimately connected to the heart of this subject and whose work is a masterful reproduction a land and time now a full century past.

Back to Cry Havoc #7 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com