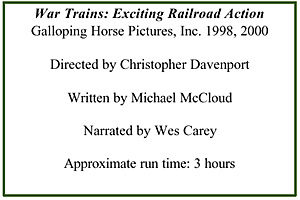

I ran across a copy of “War Trains” on DVD at a local

Tower Records. The three-episode mini-series appeared on

television starting in 1998—a sergeant I work with said that she

had seen it.

I ran across a copy of “War Trains” on DVD at a local

Tower Records. The three-episode mini-series appeared on

television starting in 1998—a sergeant I work with said that she

had seen it.

For me, it was fresh and new. I knew something about military trains, from both history books and from service in the United States Army. In Europe and the United States my military intelligence battalions conducted long-distance deployments via rail—at least for heavy equipment. I also rode the “duty train” between the “Zone” and West Berlin several times during the 1980’s.

The DVD is organized into three chapters: Combat Strategies, Subvert and Destroy and Air Attacks. Each of these chapters is about an hour long. They are a combination of vintage black and white wartime footage from World War One, World War Two, Korea, and Vietnam, and modern footage.

This is the story of American Army railroads, with limited coverage of

foreign trains. Some of the later footage, from Vietnam and the bit about moving landing craft (in tiny pieces) from an

inland steel plant to a coastal shipyard are in color. Civil War coverage is by still photographs, modern footage of

trains and battlefields. The chapters hop around chronologically. Each chapter is stand-alone; it isn’t necessary to

see the preceding chapters to enjoy the last one.

This is the story of American Army railroads, with limited coverage of

foreign trains. Some of the later footage, from Vietnam and the bit about moving landing craft (in tiny pieces) from an

inland steel plant to a coastal shipyard are in color. Civil War coverage is by still photographs, modern footage of

trains and battlefields. The chapters hop around chronologically. Each chapter is stand-alone; it isn’t necessary to

see the preceding chapters to enjoy the last one.

Combat Strategies

Compressing an hour of non-stop action into a single paragraph won’t do justice to the first episode. The chapter starts out with a Civil War battle being decided by the adroit use of existing rail transport. Railway guns, the predecessor to the cruise missile, is shown firing long range missions and taking care of heavy fortifications. As late as 1938, aircraft bombs were ineffective against fortified positions because of lack of bomb accuracy and bomb weight. American 14-inch naval rifles were mounted on rail cars and could lob a 1400-pound armor-piercing shell a maximum of 23 miles—and until the dive bomber was developed, the artillery piece could hit its target with reliability, in all weathers.

Combat Strategies covered the logistics of military railroads. The entire AEF train service organization was detailed, and there is an interesting film on building a locomotive from parts hauled across the Atlantic in parts. Contrasting this, landing craft are rail transported from an inland steel mill in the central United States to a shipyard on the west coast for assembly and launching. Both light and heavy rail lines are explained—the trench engine hauled supplies and personnel from supply depots about ten miles behind the front to a quarter mile from No Man’s Land. The standard-gauge rail lines hauled tons from ports to the depots.

Narrow-gauge trench engines had lower

silhouettes—but smoked like the big boys.

These trench engines were also front-line

ambulances for the wounded. Keeping the

rail lines up to the front was difficult, but

possible due to the static nature of trench

warfare. Moving to the Second World War

and Iran, American military trains deliver

lend-lease (and Churchill tanks?) to the

Soviets. Camp Claiborne was established in

1940 for the purpose of training military train

crews and rail support units. Rail loading an

infantry division is another War Department

film. Believe me, I left a lot out!

Narrow-gauge trench engines had lower

silhouettes—but smoked like the big boys.

These trench engines were also front-line

ambulances for the wounded. Keeping the

rail lines up to the front was difficult, but

possible due to the static nature of trench

warfare. Moving to the Second World War

and Iran, American military trains deliver

lend-lease (and Churchill tanks?) to the

Soviets. Camp Claiborne was established in

1940 for the purpose of training military train

crews and rail support units. Rail loading an

infantry division is another War Department

film. Believe me, I left a lot out!

Subvert And Destroy

Starting out with the Civil War, 7-ton mortars mounted on armored rail cars and sabotage techniques are detailed in drawings and vintage photos. The methods introduced in the Civil War are carried through to the Korean War. “The year is 1968. The place: Vietnam.”Train security in Vietnam included armored trains armed with machine guns and radios. The train in the film is followed through loading to unloading—with typically 60’s Department of Defense drama. The World War Two OSS film on “The Mole” was enlightening—the OSS tested a photo-electric trigger on a live train. The film experimented with minimum charges to wreck a train—and several times, the train survived the experiments. Ah, the best laid plans of men and moles…

Next, cavalry engineer “pioneer demolition” troops in a training film demonstrate railroad, bridge, and telegraph sabotage. Demolition packs containing 100 half-pound blocks of TNT and pioneer tools are laid out in detail. For the next trick: OSS attempting to demolish rail road tracks with minimal explosives. This second OSS film was even funnier than the first. It took multiple attempts before they got the train to derail—even after blowing thirty-six inches of rail out of the track. I got the impression that trains were resistant to derailing. Made me wonder about accidental derailment. I thought this was the best chapter in the entire series. “Italy, 1943.” The Scarifier used by German troops tore up rail road tracks—what Allied bombing didn’t do. Next up: Korea and the Han River Bridge, destroyed and rebuilt. Back to Italy, and the Corps of Engineers rebuilding broken bridges in record time—by taking shortcuts.

Suddenly, it’s September of 1918 again. The U.S. Naval Railway Battery is the subject of this chapter. A

French railway gun’s firing sequence is shown, followed by Gun # 3 of the American forces, and then it’s off to 1944

France and the Atlantic Wall. I mentioned that the series is not in chronological sequence, didn’t I?

Suddenly, it’s September of 1918 again. The U.S. Naval Railway Battery is the subject of this chapter. A

French railway gun’s firing sequence is shown, followed by Gun # 3 of the American forces, and then it’s off to 1944

France and the Atlantic Wall. I mentioned that the series is not in chronological sequence, didn’t I?

It’s back to 1918 and a hospital train in France. The vintage silent footage is narrated with a somber music track. That’s the end of another hour of “exciting railroad action” (from the subtitle!)

Air Attack

The final chapter of the “War Trains” DVD details the impact of military aviation on rail transport. Beginning in March of 1951, the video shows American air attacks on railroad bridges by North Korean forces. Switching to World War Two and the ETO, near Rome, P-47 Thunderbolts rain havoc from above. Gun camera footage to 1944 narration. “Where do planes come from? Airfields!” And airfields come from trains. Aviation engineers unload from trains and assembles a forward air field. Most of this chapter is busting German trains during World War Two.

There’s a training film on American response to enemy air attacks on their rail lines—something that wasn’t needed much due to American command of the air. One repair crew by truck and the other by motor rail car—obviously showing off all repair capabilities.

A nice piece of film on the India-Burma railway line is next. The rail line was over 800 miles long, but the glory went to the air transport “Hump” line. The China theater was huge, spanning nearly a third of Earth’s largest continent. The piece on Chinese labor carving airdromes from the wilderness may seem out of place—but the target of nearly a third of the bombs was railroads used by the Japanese. Despite heavy bombardment by aircraft, the wartime railroads kept getting through.

Air strategy to eliminate the railroad was discussed. Then the clever enemy ruses and quick repair capabilities are depicted. This portion is as relevant today as it was in World War Two. The recently-concluded invasion of Iraq showed that bomb damage assessment is as inaccurate as ever! Railroads are dispersed, run by skilled people, and tough. As long as repair parts are available, the trains will roll. It isn’t that air attacks are useless, just that even with the precision-guided munitions available during Vietnam the trains kept running. Air attacks just slowed things down and killed people and destroyed supplies.

Rail traffic had to keep moving because it was frequently the life blood of a nation’s war effort. Air attacks

did reduce the rail traffic—significantly--but didn’t stop it.

Rail traffic had to keep moving because it was frequently the life blood of a nation’s war effort. Air attacks

did reduce the rail traffic—significantly--but didn’t stop it.

War’s devastation, mostly due to air bombardment, was the backdrop for World War Two PW (prisoner of war) trains and hospital trains. The series concluded with the most important mission of the railroad—“to bring our boys back home.”

Caboose

This video covers a subject thought obsolete by most military people. Take the train? Old fashioned! Air travel is faster. Ground vehicles are more flexible. And sea transport can deposit more tonnage. Then there is the question of railroad vulnerability. Modern war doesn’t last long enough for laying in railroads—and the U.S. Army has more or less gotten rid of its railroad engineering brigades.

Air travel is faster, but when the rail line is available, heavy equipment can be moved without tying up scarce Air Force C-17, C-5, and C-141 aircraft. There aren’t enough heavy airlifters to do everything the Army needs—and the Air Force wants these birds to position their air expeditionary forces. Two weeks ago I was in a military convoy lasting close to five hours.

Rail travel saves wear and tear on vehicles, lets the troops get something resembling rest, and is more fuel efficient. True, the rail lines aren’t everywhere, but in Europe and Asia, and in parts of Africa and South America the rail lines are close enough to potential trouble spots for exploitation.

The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps has done much to develop the ability to make do without ports, and where there’s deep enough water close to the objective, sea transport makes sense. Sea transport is just one more option for the military logistician. Rail transport is another. As for railroad vulnerabilities to air attack and sabotage, the problem is overstated. Tacticians and security experts can secure rail lines—not leak-proof security, mind you, but well enough.

Military railroads are still a viable option and “War Trains” is a good place to start studying the history and use of them.

Back to Cry Havoc! # 46 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc! List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com